My last post trafficked, amongst other things, in a geography of time-space compression, so it’s time (and space) to introduce ASAP: a title chosen by Tina di Carlo, former curator of architecture and design at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and a graduate of Eyal Weizman‘s Research Architecture programme at Goldsmith’s, to echo the English ‘as soon as possible’ – ‘to evoke a sense of urgency and speed where space collapses in time’ – and, more precisely, to signal the Archive of Spatial Aesthetics and Praxis. Established in 2010, this is a virtual Aladdin’s cave of projects and practices, texts and objects.

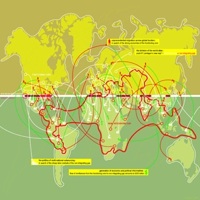

You can fossick for your own favourites – everything is accessible from the starting grid – but here are two of mine. The first is Teddy Cruz‘s Political Equator project. This uses the US/Mexico border – specifically Tijuana/San Diego – as a platform to describe an arc through other global borderlands all located between 30 and 36 degrees North:

You can fossick for your own favourites – everything is accessible from the starting grid – but here are two of mine. The first is Teddy Cruz‘s Political Equator project. This uses the US/Mexico border – specifically Tijuana/San Diego – as a platform to describe an arc through other global borderlands all located between 30 and 36 degrees North:

Along this imaginary border encircling the globe lie some of the world’s most contested thresholds: the US–Mexico border at Tijuana/San Diego, the most intensified portal for immigration from Latin America to the United States; the Strait of Gibraltar, where waves of migration flow from North African flow into Europe; the Israeli-Palestinian border that divides the Middle East, along with the embattled frontiers of Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, and Syria, and Jordan; the Line of Control between the Indian state of Kashmir and Azad or free Kashmir on the Pakistani side; the Taiwan Strait where relations between China and Taiwan are increasingly strained as the Pearl River Delta has rapidly ascended to the role of China’s economic gateway for the flow of foreign capital, supported by the traditional centers of Hong Kong and Shanghai and the paradigmatic transformations of the Chinese metropolis also characterized by urbanities of labor and surveillance.

You can find full details of the associated meetings (‘conversations’), videos and more at the project website here.

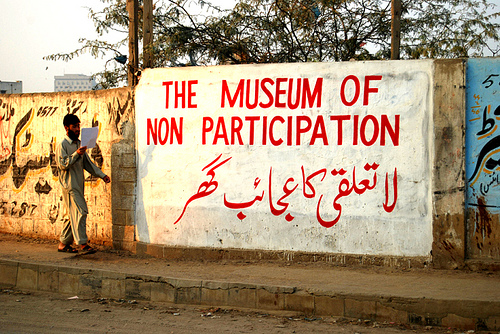

Second is Karen Mirza and Brad Butler‘s Museum of Non-Participation. This is a travelling project that started in Islamabad in 2007. The two artists watched the demonstrations by the Lawyers’ Movement against the dismissal of the Chief Justice by the Musharaf regime and the violent response by the military/police from a window in the National Art Gallery – more about the protests here and here – and went on to develop a multi-sited, multi-voiced project that has been staged in Karachi, in London’s Bethnal Green and elsewhere. One of its central aims is to contest the dominant narrative (and geographical imagination) of Pakistan as a ‘rogue state’ and to find (in part, I think, through a contrapuntal rendering of London and Karachi) ‘other languages and other voices’ to convey everyday life under the sign of the postcolonial.

ASAP explains:

The Museum of Non Participation began as a critique and ultimately exploration of the political agency of the Museum through what the artists call the space of the NON… which is at once a radical critique of the Museum which often and has historically stood by as a mute witness [and [a redefinition] of [its] traditional architectural typology, transforming it from a shelter that houses objects to a literal sign that travels around.

You can download a detailed (30pp) feature from Kaleidoscope here.

The Museum was in Vancouver this month, where it included a screening of Deep State (2012) , a film developed in collaboration with China Miéville (and my thanks to Jorge Amigo for the notice). Here is a preview:

The film takes its title from the Turkish term ‘Derin Devlet’, meaning ‘state within the state’. Although its existence is impossible to verify, this shadowy nexus of special interests and covert relationships is the place where real power is said to reside, and where fundamental decisions are made – decisions that often run counter to the outward impression of democracy.

Amorphous and unseen, the influence of this deep state is glimpsed at regular points throughout the film – most clearly surfacing in its reflexive responses to popular protest, and in legislated acts of violence and containment, but also rumbling and reverberating, deeper down, in an eternally recurring call-and-response between rhetorical positions and counter-languages, in which a raised fist, a thrown rock, a crowd surge, an occupation provoke a corresponding reaction in the form of a police charge, a baton attack, a pepper spray, assassinations.

There’s an interview with Mirza and Butler about the film here, where Mirza explains that when she read Miéville’s The city in the city she was struck by the ‘condition of unseeing in the midst of seeing’ which is at the heart of the book. Miéville’s extraordinary combination of a radical reading of international law – in his Between equal rights: a Marxist theory of international law (2006) and also, for example, here –and what he calls his ‘weird fiction’ was not only a ‘compelling combination’ but also a creative platform from which to develop a script and then the screenplay. Michael Turner provides both a sympathetic account of the Museum project and a spirited critique of the Vancouver screening here (there’s also a constructive response: scroll down).

There’s an interview with Mirza and Butler about the film here, where Mirza explains that when she read Miéville’s The city in the city she was struck by the ‘condition of unseeing in the midst of seeing’ which is at the heart of the book. Miéville’s extraordinary combination of a radical reading of international law – in his Between equal rights: a Marxist theory of international law (2006) and also, for example, here –and what he calls his ‘weird fiction’ was not only a ‘compelling combination’ but also a creative platform from which to develop a script and then the screenplay. Michael Turner provides both a sympathetic account of the Museum project and a spirited critique of the Vancouver screening here (there’s also a constructive response: scroll down).