Laleh Khalili – whose work on the new and old classics of counterinsurgency, on the gendering of counterinsurgency, and on the location of Palestine in global counterinsurgency – is indispensable, has just alerted me to the fate (Fate?) of one of its principal architects, David Kilcullen.

In The accidental guerilla and other writings, Kilcullen – Petraeus’s Senior Counterinsurgency Adviser in Iraq – repeatedly turned to bio-medical analogies to advance a bio-political vision of counterinsurgency: insurgency as a ‘social pathology’ whose prognosis can be traced through the stages of infection, contagion, intervention and rejection (‘immune response’). In an interview with Fast Company, Kilcullen now explains that he

“came out of Iraq with a real conviction that we tend to think that a bunch of white guys turning up with a solution fixes all the problems. It doesn’t work like that. You actually have to really build a collaborative relationship with the people on the ground if you want to have any hope of understanding what’s going on.”

Kilcullen’s contract ended when the Obama administration came into office, and he founded Caerus Associates. The company advertises itself as ‘a strategy and design firm’ that works to ‘help governments, global enterprises, and local communities thrive in complex, frontier environments.’ It claims to ‘bring the system into focus’ by providing ‘strategic design for a world of overlapping forces — urbanization, new market horizons, resource scarcity and conflict — to build resilience and capacity.’ The company explains its ‘strategic design process’ here, and Kilcullen’s vision of systems analysis is sketched here. This may sound like the rapid-fire buzz-words that corporate start-ups typically shoot at their clients, but Kilcullen provides Fast Company with a sawn-off version (it’s really hard to avoid these metaphors…):

“We’re two-thirds tech, one-thirds social science, with a dash of special operations… We can go out in a community and say, ‘Let’s map who owns what land,’ or ‘Let’s map who owes the local warlord money,’ or ‘Let’s map the areas in the city where you don’t feel safe.'”

This chimes with Kilcullen’s famous description of contemporary counterinsurgency as ‘armed social work’, and in an interview with the International Review of the Red Cross published in September 2011 Kilcullen extended his vision of ‘military humanism’ beyond insurgency thus:

‘The methods and techniques used by illegal armed groups of all kinds are very similar, irrespective of their political objectives. So whether you’re talking about a gang in the drug business in Latin America, or organized crime in the gun-running or human smuggling business, or whether you’re talking about an insurgency or perhaps even a civil war involving tribes, you will see very similar approaches and techniques being used on the part of those illegal armed groups. That’s one of the reasons why I believe counter-insurgency isn’t a very good concept for the work that the international community is trying to do. I think that the idea of complex humanitarian emergencies is actually a lot closer to the reality on the ground. You almost never see just one insurgent group fighting an insurgency against the government anymore. What you typically see is a complex, overlapping series of problems, which includes one or more or dozens of armed groups. And the problem is one of stabilizing the environment and helping communities to generate peace at the grassroots level – a bottom-up peace-building process. And that’s not a concept that really fits very well with traditional counter-insurgency, which is about defeating an insurgent movement and is a top-down, state-based approach. What you have to do is create an environment where existing conflicts can be dealt with in a non-violent way.’

This is a remarkable passage for several reasons: the focus on ‘techniques’ not ‘objectives’, which works to de-politicize and de-contextualize a range of different situations in order to generalize about them, the appeal to a collective “international community” whose only interest is a generic “peace”, and hence the passage to what Eyal Weizman calls ‘the humanitarian present’. I think that’s also a colonial present, not surprisingly: ‘humanitarianism’ was often the velvet glove wrapped around the iron fist of colonialism. But what Weizman sees as novel about the present is the way in which its ‘economy of violence is calculated and managed’ by a series of moral technologies (the term is Adi Ophir‘s) that work to continue and legitimize its operation. In other words, there is today an intimate collusion of the ‘technologies of humanitarianism, human rights and humanitarian law with military and political powers’.

Despite the reference to ‘special operations’ in the Fast Company interview – something which makes me think that Obama would have found Kilcullen’s continued advice invaluable – Kilcullen insists that it’s a collaborative process:

“We specialize in working with communities that are under the threat of violence in frontier environments, and I think to some extent that distinguishes us a little bit from other people. Sure we can give a slick presentation in a hotel room, but what we can also do is walk the street in dangerous places, engage with communities, and figure out what needs to happen. It’s not us figuring it out, it’s them telling us, but often we find that no one’s ever been there and asked them before.”

‘Dangerous places’, ‘frontiers’: this is still the language of adventurism. It recalls Zygmunt Bauman‘s ‘planetary frontierland’, and even more Mark Duffield on the ‘global borderlands’:

‘The idea of the borderlands … does not reflect an empirical reality. It is a metaphor for an imagined geographical space where, in the eyes of many metropolitan actors and agencies, the characteristics of brutality, excess and breakdown predominate. It is a terrain that has been mapped and re-mapped in innumerable aid and academic reports where wars occur through greed and sectarian gain, social fabric is destroyed and developmental gains reversed, non-combatants killed, humanitarian assistance abused and all civility abandoned.’

It’s not surprising, then, that in the IRC interview Kilcullen should make so much of establishing ‘the rule of law’: ‘It’s a set of rules which has predictable consequences and allows the population to feel safe, and helps them know what they need to do in order to be in a safe place.’ He makes it clear that, in many (perhaps most) circumstances ‘bottom-up, community-based law, which can be transitional justice, or customary law, applied by traditional courts or religious courts, is as effective and possibly even more effective in the initial stages than central-state structures.’ But this ignores the multiple ways in which law (including international humanitarian law) is not apart from conflict but is almost always a part of conflict: as Weizman has it, ‘international law develops through its violation. In modern war, violence legislates.’

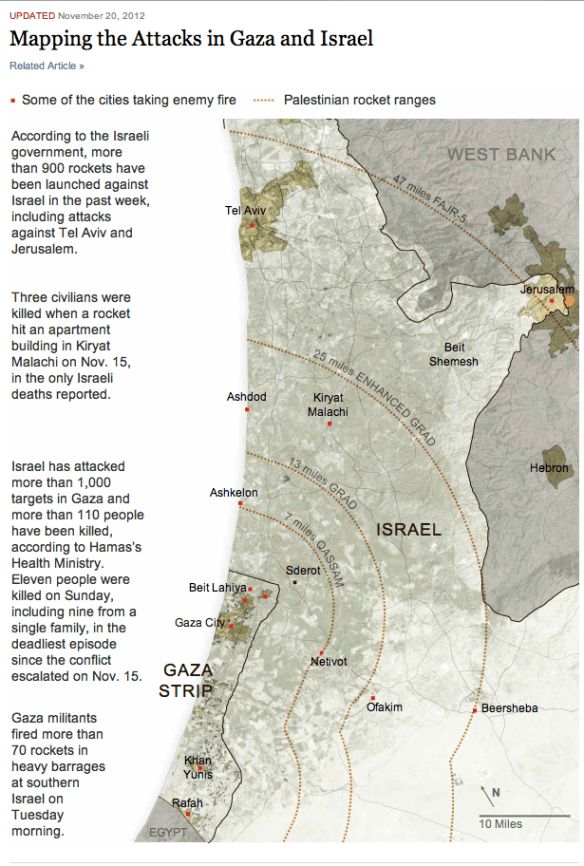

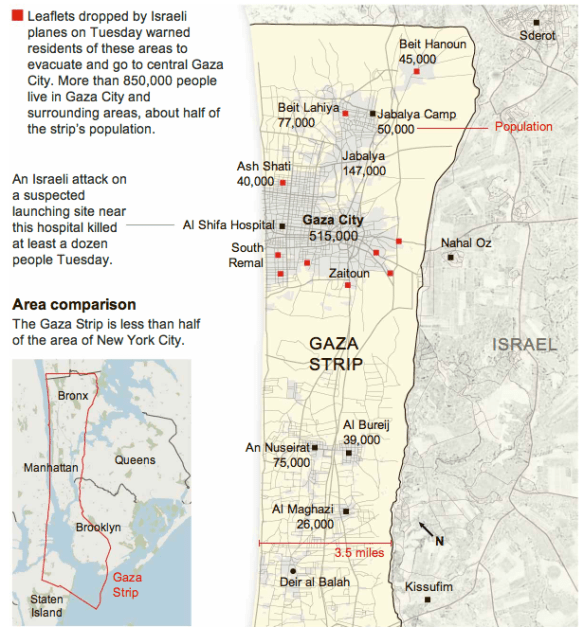

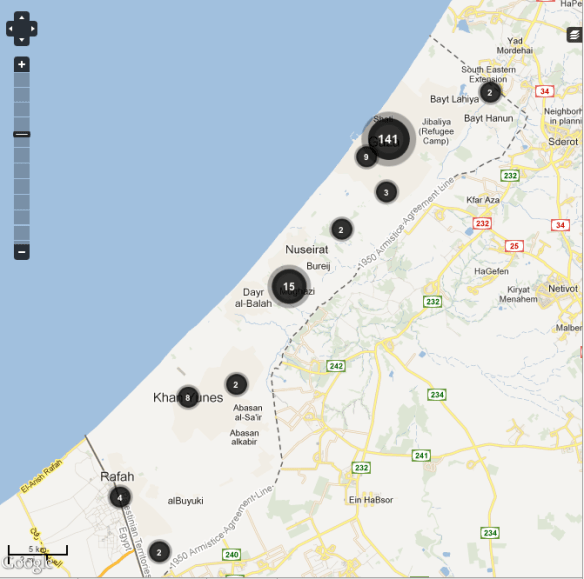

One could say much the same about maps. Mapping is not a neutral, objective exercise; mapping is performative and its material effects depend on the constellation of powers and practices within which it is deployed. Kilcullen’s injunction – “Let’s map” – glosses over who the ‘us’ is, who is included and who is excluded, and the process through which some mappings are accorded legitimacy while others are disavowed. This is also one of Weizman’s central claims, not least in his exposure of the torturous mappings that issued in the Hollow Land of occupied Palestine.

Weizman’s particular focus in his discussion of the humanitarian present is Gaza, and this winds me back to Laleh Khalili’s work which brilliantly re-reads counterinsurgency in occupied Palestine contrapuntally with US counterinsurgency practices elsewhere. Her Essential Reading on Counterinsurgency was published by Jadaliyya, and her forthcoming book, Time in the shadows: Confinement in Counterinsurgencies (Stanford University Press, October 2012), engages with a Medusa’s raft of counterinsurgency adviser-survivors, including Kilcullen and Andrew Exum (Abu Muqawama).

And so a final question: how would ‘strategic design’ and a ‘collaborative process’ help the people of Gaza? Whose ‘rule of law’ is to be established? And which maps chart a road not only to peace but to justice for the people of Palestine?