A follow-up to my post on the demise of the US military’s Human Terrain System: an interesting report from Vanessa Gezari in the New York Times. She’s the author of The Tender Soldier, a first-hand account of the Human Terrain System, and she starts her Times essay by recalling her own experience accompanying a US patrol in Afghanistan in 2010:

A follow-up to my post on the demise of the US military’s Human Terrain System: an interesting report from Vanessa Gezari in the New York Times. She’s the author of The Tender Soldier, a first-hand account of the Human Terrain System, and she starts her Times essay by recalling her own experience accompanying a US patrol in Afghanistan in 2010:

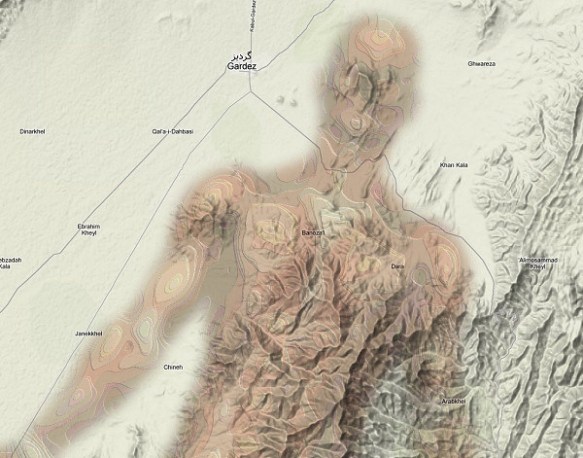

Cultural training and deep, nuanced understanding of Afghan politics and history were in short supply in the Army; without them, good intelligence was hard to come by, and effective policy making was nearly impossible. Human Terrain Teams, as Human Terrain System units were known, were supposed to include people with social-science backgrounds, language skills and an understanding of Afghan or Iraqi culture, as well as veterans and reservists who would help bind the civilians to their assigned military units.

On that winter day in Zormat, however, just how far the Human Terrain System had fallen short of expectations was clear. Neither of the social scientists on the patrol that morning had spent time in Afghanistan before being deployed there. While one was reasonably qualified, the other was a pleasant 43-year-old woman who grew up in Indiana and Tennessee, and whose highest academic credential was an advanced degree in organizational management she received online. She had confided to me that she didn’t feel comfortable carrying a gun she was still learning how to use. Before arriving in Afghanistan, she had traveled outside the United States only once, to Jamaica — “and this ain’t Jamaica,” she told me…

The shortcomings I saw in Zormat were hardly the extent of the Human Terrain System’s problems. The project suffered from an array of staffing and management issues, coupled with internal disagreements over whether it was meant to gather intelligence, hand out protein bars and peppermints, advise commanders on tribal conflicts or all three — a lack of clear purpose that eventually proved crippling. It outraged anthropologists, who argued that gathering information about indigenous people while embedded in a military unit in active combat posed an intractable ethical conflict. Once the subject of dozens of glowing news stories, the program had fallen so far off reporters’ radar by last fall that the Army was able to quietly pull the plug without a whisper in the mainstream media.

She suggests that the military could – and should – have learned from its previous attempts to enlist social scientists in Vietnam, Central America and elsewhere, and points to Seymour Deitchman‘s The Best-Laid Schemes: A tale of social science research and bureaucracy (1976), which is available as an open access download from the US Marine Corps University Press here.

She suggests that the military could – and should – have learned from its previous attempts to enlist social scientists in Vietnam, Central America and elsewhere, and points to Seymour Deitchman‘s The Best-Laid Schemes: A tale of social science research and bureaucracy (1976), which is available as an open access download from the US Marine Corps University Press here.

Deitchman worked for the Pentagon as a counterinsurgency advisor (among many other roles), and his account was a highly personal, take-no-prisoners affair.

Part of the problem, he insisted, was the language of the social sciences:

There’s much more in a similar vein, and not surprisingly, Deitchman’s conclusion about the military effectiveness of social science was a jaundiced one.

The community of social science is likely to urge and has urged that increased government support of research on the great social problems of the day. With due recognition for the government’s need to collect data to help it plan and evaluate the social programs it is expected to undertake, I have reached the conclusion, nevertheless, that the opposite of the social scientists’ recommendation is in order. The research is needed, without question. Some of it, especially in the evaluation area, is necessary and feasible for government to sponsor. Beyond this, its support should be subject to the economic and political laws of the intellectual marketplace. And the government should do less, not more, to influence the workings of that marketplace. It should support less, not more, research into the workings of society.

You couldn’t make it up (or perhaps they did). But this isn’t Vanessa’s view. ‘The need for cultural understanding isn’t going away,’ she insists:

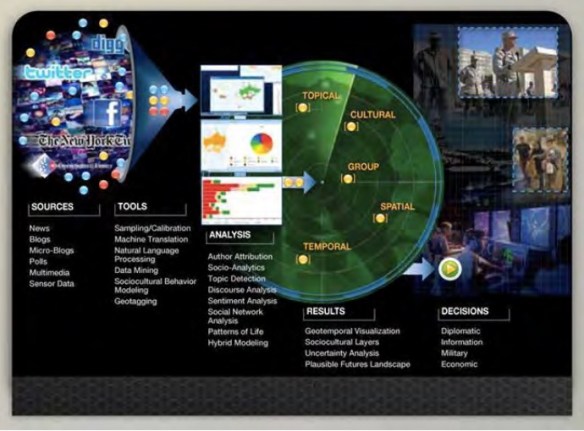

The rise of drones and sociocultural modeling, which uses data to simulate and sometimes predict human responses to conflict and crisis, have given some in the defense establishment the idea that we can do all our fighting safely, from a distance. But we’ve had this idea before, in the decades following Vietnam, and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan should have reminded us of its falsity.