I’ve posted before about the ways in which the First World War involved the calibration and even mathematisation of the battle space, and it’s an important part of my argument in Gabriel’s Map (as you can see from the slides under the DOWNLOADS tab), but this in its turn required an elaborate choreography of time. This is clearest in the co-ordination of artillery and infantry, particularly in the calculations required for a ‘creeping barrage’ in support of an advance, and eventually involved co-ordination with air support too, but it extended back far beyond the front lines; the re-supply and re-deployment of troops along narrow, crowded roads or narrow-gauge railways also required elaborate timetables, as Ernst Jünger makes clear in this passage from Storm of Steel:

‘The roads were choked with columns of marching men, innumerable guns and an endless supply column. Even so, it was all orderly, following a carefully worked-out plan by the general staff. Woe to the outfit that failed to keep to its allotted time and route; it would find itself elbowed into the gutter and having to wait for hours till another slot fell vacant’ (pp. 222-3).

But how, exactly, were these offensive and logistical timetables orchestrated? What was the mechanism for what Billy Bishop called ‘clockwork warfare’?

Jünger himself provides just one (German) example: ‘‘To keep everyone synchronised, on the dot of noon every day a black ball was lowered from the observation balloons, which disappeared at ten past twelve.’ This was presumably a battlefield adaptation of the ‘time-balls’ that had been developed by the British and then the US navies in the nineteenth century, but other ways of marking time on the Front seem to have been more common.

Two technologies were pressed into service by the Allies; they can both be seen in this synchronisation instruction contained in Operation Order (no 233) from the 112th Infantry Brigade on 10 October 1918:

O.C. No.2 Section, 41st Divisional Signal Company, will arrange for EIFFEL TOWER Time to be taken at 11.49 on “J” minus one day [“J” was the day of the attack] and afterwards will synchronise watches throughout the Brigade Group by a “rated” watch.

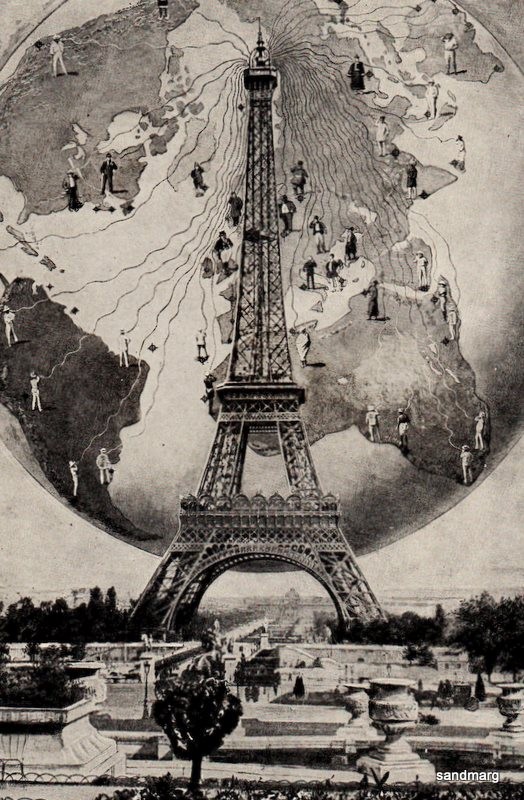

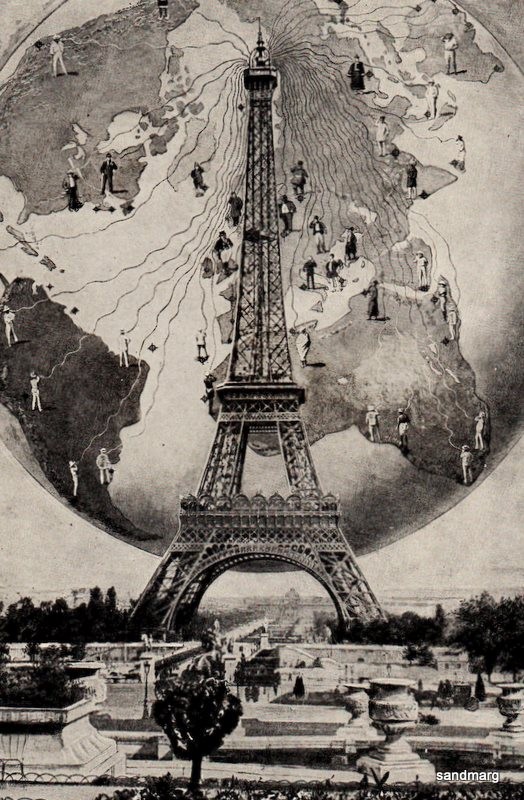

The first was the Eiffel Tower – or, more accurately, the time-signal transmitted from the Eiffel Tower throughout the war. In 1909 the original twenty-year lease for the Tower was about to expire, and many Parisians loathed it (Maupassant famously had lunch there every day because it was the one place in the city from which it couldn’t be seen) so that its demolition seemed imminent. But it was saved in large measure because the French military was persuaded of its strategic value as a navigation and wireless beacon. Eiffel had allowed the Minister of War to place antennas at the top in 1903, and the Bureau des Longitudes (under the direction of Henri Poincaré) urged the development of the military radio-telegraphic station to broadcast time-signals twice daily. The original intention was to enable mariners to set their chronometers, but the project had a wider strategic, scientific and symbolic significance. ‘Wireless simultaneity’, writes Peter Galison, ‘had become a military as well as a civilian priority’.

An experimental service started in 1909, and the French Army began broadcasts on 23 May 1910; by June 1913 a regular time service (based on transmissions from the master-clock at the Paris Observatory to the Tower) was in operation. This continued throughout the war and in to the 1920s; the ‘ordinary time signals’, which were broadcast each day at 10.45 a.m., 10.47 a.m. and 10.49 a.m. and again at 11.45 p.m., 11.47 p.m. and 11.49 p.m., enabled ‘an expert observer, under the most favourable circumstances, to take the time to nearly 0.1 second’. There’s more technical information than you could possible want here, but the meat of the story is in Peter Galison’s brilliant Einstein’s clocks, Poincaré’s maps: empires of time (2003) (for a discussion and overview see here).

The second requirement for choreographing time in the battlespace was the wristwatch. Originally wristwatches were designed for women (the first “wristlet” was made by Philippe Patek in 1868), and although the Kaiser had 2,000 wristwatches made for his naval officers in 1880 – and there is some evidence of their use in the Boer War – men continued to favour pocket-watches until the First World War. Both soldiers and aviators needed a hands-free way of telling the time, and so the “trench watch” was born. In Knowledge for War: Every officer’s handbook for the front, published in 1916, a wristwatch headed the kit list, above even a revolver and field glasses, and in the same year one manufacturer claimed that ‘one soldier in every four’ was already wearing a wristwatch ‘and the other three mean to get one as soon as they can.’

The second requirement for choreographing time in the battlespace was the wristwatch. Originally wristwatches were designed for women (the first “wristlet” was made by Philippe Patek in 1868), and although the Kaiser had 2,000 wristwatches made for his naval officers in 1880 – and there is some evidence of their use in the Boer War – men continued to favour pocket-watches until the First World War. Both soldiers and aviators needed a hands-free way of telling the time, and so the “trench watch” was born. In Knowledge for War: Every officer’s handbook for the front, published in 1916, a wristwatch headed the kit list, above even a revolver and field glasses, and in the same year one manufacturer claimed that ‘one soldier in every four’ was already wearing a wristwatch ‘and the other three mean to get one as soon as they can.’

The first models had hinged covers (above), and often simply added lugs to existing small pocket-watches; wristwatches were widely advertised and bought commercially, but from 1917 the War Department began to procure and issue trench watches to officers for field trials. Trench watches usually had luminous dials, for obvious reasons, and many models had ‘shrapnel guards’ (below).

If you want to know more, the Military Watch Resource (really) is the place to go; there’s also Konrad Knirim‘s 800 pp British Military Timepeieces…

The military importance of the wristwatch was captured in this essay in Stars and Stripes, published on 15 February 1918:

‘I am the wrist watch…

‘I am the wrist watch…

From the general down to the newly-arrived buck private, they all wear me, they all swear by me instead of at me.

On the wrist of every line officer in the front line trenches, I point to the hour, minute and second at which the waiting men spring from the trenches to the attack.

I … am the final arbiter as to when the barrage shall be laid down, when it shall be advanced, when it shall case, when it shall resume. I need but point with my tiny hands and the signal is given that means life or death to thousands upon thousands.

My phosphorous glow soothes and charms the chilled sentry, as he stands, waist deep in water amid the impenetrable blackness, and tells him how long he must watch there before his relief is due.

‘I mount guards, I dismiss guards. Everything that is done in the army itself, that is done for the army behind the lines, must be done according to my dictates. True to the Greenwich Observatory, I work over all men in khaki my rigid and imperious sway…

I am in all and of all, at the heart of every move in this man’s war. I am the witness of every action, the chronicler of every second that the war ticks on… I am, in this way, the indispensable, the always-to-be-reckoned-with.

I am the wrist watch.’

There were two ways in which watches were synchronised. Usually Signals Officers or orderlies were ordered to report to headquarters, as in this Instruction from the 169th Infantry Brigade on 14 August 1914:

Units will synchronise watches by sending orderlies to be at Brigade Headquarters with watches to receive the official time on “Y” day at the following hours:- 9 a.m, 5 p.m., 8 p.m

And again, in this Operation Order from the 89th Infantry Brigade on 29 July 1916:

One Officer from each Company will report to Battalion Headquarters in the SUNKEN ROAD at 2.30 a.m. 30th July, to synchronise watches.

Intelligence officers from 4th Brigade AIF synchronising watches near Hamelet, 3 July 1918 (Australian War Memorial)

But centralisation also requires re-distribution, so to speak, as this order from 112 Infantry Brigade later in October 1918 makes clear:

Watches will be synchronised at 0630, 20th inst. Brigade Signal Officer will send watch round Units.

Edmund Blunden describes the practice in Undertones of War: ‘Watches were synchronized and reconsigned to the officers’; and again: ‘A runner came round distributing our watches, which had been synchronized at Bilge Street [‘battle headquarters’]’.

By these various means, then, as Stephen Kern put it in The culture of time and space, 1880-1918,

By these various means, then, as Stephen Kern put it in The culture of time and space, 1880-1918,

‘The war imposed homogeneous time… The delicate sensitivity to private time of Bergson and Proust had no place in the war. It was obliterated by the overwhelming force of mass movements that regimented the lives of millions of men by the public time of clocks and wrist watches, synchronized to maximize the effectiveness of bombardments and offensives.’

That’s surely an over-statement: just as the ‘optical war’ produced through a profoundly cartographic vision was supplemented, subverted and even resisted by quite other, intimately sensuous geographies – what I’ve called a ‘corpography’ – so, too, must the impositions and regimentations of the hell of Walter Benjamin‘s ‘homogeneous, empty time’ have been registered and on occasion even refused in the persistence of other, more personal temporalities.

Note: For indispensable help in thinking through these issues, I’m indebted to contributors to the Great War Forum who patiently and generously responded to my original question: ‘When watches were synchronised what, exactly, were they synchronised to, and how was it done?’