The flu has restricted me to not so much light reading as lighter-than-air reading, so here are some short contributions and notices that appeared during the Christmas break and which address various aspects of (later) modern war and military violence:

Peter Schwartzstein on ‘The explosive secrets of Egypt’s deserts‘ – the recovery of military maps, aerial photographs, personal journals and sketchbooks from the Second World War to plot the vast minefields that continue to haunt ‘one of the most hotly contested killing fields of the twentieth century’. You can find more in Aldino Bondesan‘s ‘Between history and geography: The El Alamein Project’, in Jill Edwards (ed) El Alamein and the struggle for North Africa (Oxford, 2012).

I discussed those minefields in ‘The natures of war’ (DOWNLOADS tab), and that essay intersects in all sorts of ways with my good friend Gastòn Gordillo‘s project on terrain, so here is a short reflection from him entitled Terrain, forthcoming in Lexicon for an Anthropocene Yet Unseen.

Not the ‘war on drugs’ but the war through drugs: Mike Jay‘s sharp review essay (‘Don’t fight sober’) on Łukasz Kamieński‘s brilliantly titled Shooting Up: a short history of drugs and war and Norman Ohler‘s over-the-top Blitzed: drugs in Nazi Germany (for another, equally critical take on Ohler, see Richard J Evans‘s splenetic review here; more – and more appreciative – from Rachel Cooke‘s interview with Ohler here).

Here’s an extract from Mike’s review:

In Shooting Up, a historical survey of drugs in warfare that grew out of his research into future military applications of biotechnology, Łukasz Kamieński lists some of the obstacles to getting the facts straight. State authorities tend to cloak drug use in secrecy, for tactical advantage and because it frequently conflicts with civilian norms and laws. Conversely it can be exaggerated to strike fear into the enemy, or the enemy’s success and morale can be imputed to it. When drugs are illegal, as they often are in modern irregular warfare, trafficking or consumption is routinely denied. The negative consequences of drug use are covered up or explained away as the result of injury or trauma, and longer-term sequels are buried within the complex of post-traumatic disorders. Soldiers aren’t fully informed of the properties and potency of the drugs they’re consuming. Different perceptions of their role circulate even among participants fighting side by side.

In Shooting Up, a historical survey of drugs in warfare that grew out of his research into future military applications of biotechnology, Łukasz Kamieński lists some of the obstacles to getting the facts straight. State authorities tend to cloak drug use in secrecy, for tactical advantage and because it frequently conflicts with civilian norms and laws. Conversely it can be exaggerated to strike fear into the enemy, or the enemy’s success and morale can be imputed to it. When drugs are illegal, as they often are in modern irregular warfare, trafficking or consumption is routinely denied. The negative consequences of drug use are covered up or explained away as the result of injury or trauma, and longer-term sequels are buried within the complex of post-traumatic disorders. Soldiers aren’t fully informed of the properties and potency of the drugs they’re consuming. Different perceptions of their role circulate even among participants fighting side by side.

Kamieński confines the use of alcohol in war to his prologue and wisely so, or the rest of the book would risk becoming a footnote to it. A historical sweep from the Battle of Hastings to Waterloo or ancient Greece to Vietnam suggests that war has rarely been fought sober. This is unsurprising in view of the many different functions alcohol performs. It has always been an indispensable battlefield medicine and is still pressed into service today as antiseptic, analgesic, anaesthetic and post-trauma stimulant. It has a central role in boosting morale and small-group bonding; it can facilitate the private management of stress and injury; and it makes sleep possible where noise, discomfort or stress would otherwise prevent it. After the fighting is done, it becomes an aid to relaxation and recovery.

All these functions are subsidiary to its combat role and Kamieński’s particular interest, the extent to which drugs can transform soldiers into superhuman fighting machines. ‘Dutch courage’ – originally the genever drunk by British soldiers during the Thirty Years’ War – has many components. With alcohol, soldiers can tolerate higher levels of pain and hardship, conquer fear and perform acts of selfless daring they would never attempt without it. It promotes disinhibition, loosens cultural taboos and makes troops more easily capable of acts that in civilian life would be deemed criminal or insane. The distribution of alcohol and other drugs by medics or superior officers has an important symbolic function, giving soldiers permission to perform such acts and to distance themselves from what they become when they’re intoxicated.

Opium, cannabis and coca all played supporting roles on the premodern battlefield but it was only with the industrialisation of pharmaceutical production that other drugs emerged fully from alcohol’s shadow. Morphine was widely used for the first time in the American Civil War and the 19th-century cocaine boom began with research into its military application. Freud was first alerted to it by the work of the army surgeon Theodor Aschenbrandt, who in 1883 secretly added it to the drinking water of Bavarian recruits and found that it made them better able to endure hunger, strain and fatigue. During the First World War cocaine produced in Java by the neutral Dutch was exported in large quantities to both sides. British forces could get it over the counter in products such as Burroughs Wellcome’s ‘Forced March’ tablets, until alarms about mass addiction among the troops led to a ban on open sales under the Defence of the Realm Act in 1916.

During the 1930s a new class of stimulants emerged from the laboratory, cheap to produce, longer-acting and allegedly less addictive. Amphetamine was first brought to market in the US by Smith, Kline and French in 1934 in the form of a bronchial inhaler, Benzedrine, but its stimulant properties were soon recognised and it was made available in tablet form as a remedy for narcolepsy and a tonic against depression. As with cocaine, one of its first applications was as a performance booster in sport. Its use by American athletes during the Munich Olympic Games in 1936 brought it to the attention of the German Reich and by the end of the following year the Temmler pharmaceutical factory in Berlin had synthesised a more powerful variant, methamphetamine, and trademarked it under the name Pervitin. As Norman Ohler relates in Blitzed, research into its military applications began almost immediately; it was used in combat for the first time in the early stages of the Second World War. Ohler’s hyperkinetic, immersive prose evokes its subjective effects on the German Wehrmacht far more vividly than any previous account, but it also blurs the line between myth and reality.

During the 1930s a new class of stimulants emerged from the laboratory, cheap to produce, longer-acting and allegedly less addictive. Amphetamine was first brought to market in the US by Smith, Kline and French in 1934 in the form of a bronchial inhaler, Benzedrine, but its stimulant properties were soon recognised and it was made available in tablet form as a remedy for narcolepsy and a tonic against depression. As with cocaine, one of its first applications was as a performance booster in sport. Its use by American athletes during the Munich Olympic Games in 1936 brought it to the attention of the German Reich and by the end of the following year the Temmler pharmaceutical factory in Berlin had synthesised a more powerful variant, methamphetamine, and trademarked it under the name Pervitin. As Norman Ohler relates in Blitzed, research into its military applications began almost immediately; it was used in combat for the first time in the early stages of the Second World War. Ohler’s hyperkinetic, immersive prose evokes its subjective effects on the German Wehrmacht far more vividly than any previous account, but it also blurs the line between myth and reality.

This too blurs the line between myth and reality, or so you might think. Geoff Manaugh‘s ever-interesting BldgBlog reports that the US Department of Defense ‘is looking to develop “biodegradable training ammunition loaded with specialized seeds to grow environmentally beneficial plants that eliminate ammunition debris and contaminants”.’ Sustainable shooting. But notice this is ammunition only for use in proving grounds…

At the other end of the sustainable spectrum, John Spencer suggests that ‘The most effective weapon on the modern battlefield is concrete‘. To put it simply, you bring today’s liquid wars to a juddering halt – on the ground at any rate – by turning liquidity into solidity and confounding the mobility of the enemy:

Ask any Iraq War veteran about Jersey, Alaska, Texas, and Colorado and you will be surprised to get stories not about states, but about concrete barriers. Many soldiers deployed to Iraq became experts in concrete during their combat tours. Concrete is as symbolic to their deployments as the weapons they carried. No other weapon or technology has done more to contribute to achieving strategic goals of providing security, protecting populations, establishing stability, and eliminating terrorist threats. This was most evident in the complex urban terrain of Baghdad, Iraq. Increasing urbanization and its consequent influence on global patterns of conflict mean that the US military is almost certain to be fighting in cities again in our future wars. Military planners would be derelict in their duty if they allowed the hard-won lessons about concrete learned on Baghdad’s streets to be forgotten.

When I deployed to Iraq as an infantry soldier in 2008 I never imagined I would become a pseudo-expert in concrete, but that is what happened—from small concrete barriers used for traffic control points to giant ones to protect against deadly threats like improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and indirect fire from rockets and mortars. Miniature concrete barriers were given out by senior leaders as gifts to represent entire tours. By the end my deployment, I could tell you how much each concrete barrier weighed. How much each barrier cost. What crane was needed to lift different types. How many could be emplaced in a single night. How many could be moved with a military vehicle before its hydraulics failed.

Baghdad was strewn with concrete—barriers, walls, and guard towers. Each type was named for a state, denoting their relative sizes and weights. There were small barriers like the Jersey (three feet tall; two tons), medium ones like the Colorado (six feet tall; 3.5 tons) and Texas (six feet, eight inches tall; six tons), and large ones like the Alaska (12 feet tall; seven tons). And there were T-walls (12 feet tall; six tons), and actual structures such as bunkers (six feet tall; eight tons) and guard towers (15 to 28 feet tall).

But it’s nor only a matter of freezing movement:

Concrete also gave soldiers freedom to maneuver in urban environments. In the early years of the war, US forces searched for suitable spaces in which to live. Commanders looked for abandoned factories, government buildings, and in some situations, schools. Existing structures surrounded by walled compounds of some type were selected because there was little in the environment to use for protection—such as dirt to fill sandbags, earthworks, or existing obstacles. As their skills in employing concrete advanced, soldiers could occupy any open ground and within weeks have a large walled compound with hardened guard towers.

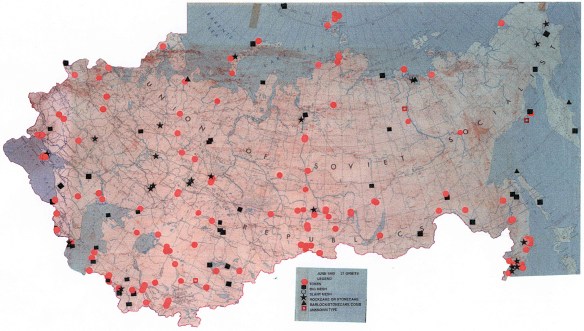

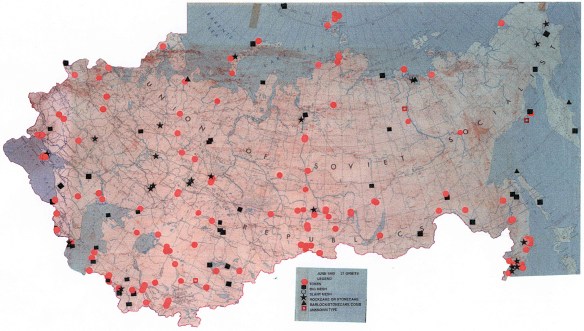

Now up into the air. My posts on the US Air Force’s Bombing Encyclopedia (here and here) continue to attract lots of traffic; I now realise that the project – a targeting gazetteer for Strategic Air Command – needs to be understood in relation to a considerable number of other texts. Elliott Child has alerted me to the prisoner/defector interrogations that provided vital intelligence for the identification of targets – more soon, I hope – while those targets also wound their way into the President’s Daily Brief (this was an era when most Presidents read the briefs and took them seriously, though Nixon evidently shared Trump’s disdain for the CIA: see here.) James David has now prepared a National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book (No 574) which provides many more details based on redacted releases of Briefs for the period 1961-77.

Two of the most critical intelligence targets throughout the Cold War were Soviet missile and space programs. U.S. intelligence agencies devoted a huge amount of resources to acquiring timely and accurate data on them. Photoreconnaissance satellites located launch complexes and provided data on the number and type of launchers, buildings, ground support equipment, and other key features. They located R&D centers, manufacturing plants, shipyards, naval bases, radars, and other facilities and obtained technical details on them. The satellites also occasionally imaged missiles and rockets on launch pads. There were four successful photoreconnaissance satellite programs during the four administrations in question. CORONA, a broad area search system, operated from August 1960 until May 1972. The first successful high resolution system, GAMBIT-1, flew from 1963-1967. The improved GAMBIT-3 high resolution satellite was launched from 1966-1984. HEXAGON, the broad area search successor to CORONA, operated from 1971-1984. High-resolution ground photography of missiles and rockets displayed at Moscow parades and other events also proved valuable at times.

Signals intelligence platforms [above] also contributed greatly to understanding Soviet missile and space programs. Satellites such as GRAB (1960-1962), POPPY (1962-1971), and AFTRACK payloads (1960-1967) located and intercepted air defense, anti-ballistic missile, and other radars and added significantly to U.S. knowledge of Soviet defensive systems and to the development of countermeasures. Other still-classified signals intelligence satellites launched beginning around 1970 reportedly intercepted telemetry and other data downlinked from missiles, rockets, and satellites to Soviet ground stations, and commands uplinked from the stations to these vehicles. Antennas at intercept sites also recorded this downlinked data. During the latter stages of missile and rocket tests to the Kamchatka Peninsula and the Pacific, ships and aircraft also intercepted telemetry and acquired optical data of the vehicles. Analysis of the telemetry and other data enabled the intelligence agencies to determine the performance characteristics of missiles, rockets, and satellites and helped establish their specific missions. Radars at ground stations detected launches, helped determine missile trajectories, observed the reentry of vehicles, and assisted in estimating the configuration and dimensions of missiles and satellites. Space Surveillance Network radars and optical sensors detected satellites and established their orbital elements. The optical sensors apparently also photographed satellites.

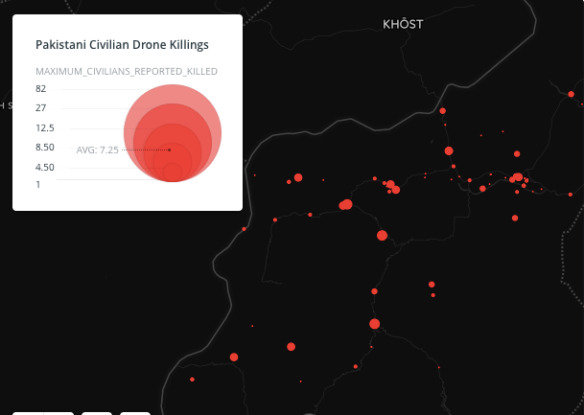

And for a more recent take on sensors and shooters, coming from Yale in the Spring: Christopher J Fuller‘s See It/Shoot It: The secret history of the CIA’s lethal drone program:

An illuminating study tracing the evolution of drone technology and counterterrorism policy from the Reagan to the Obama administrations.

This eye-opening study uncovers the history of the most important instrument of U.S. counterterrorism today: the armed drone. It reveals that, contrary to popular belief, the CIA’s covert drone program is not a product of 9/11. Rather, it is the result of U.S. counterterrorism practices extending back to an influential group of policy makers in the Reagan administration.

Tracing the evolution of counterterrorism policy and drone technology from the fallout of Iran-Contra and the CIA’s “Eagle Program” prototype in the mid-1980s to the emergence of al-Qaeda, Fuller shows how George W. Bush and Obama built upon or discarded strategies from the Reagan and Clinton eras as they responded to changes in the partisan environment, the perceived level of threat, and technological advances. Examining a range of counterterrorism strategies, he reveals why the CIA’s drones became the United States’ preferred tool for pursuing the decades-old goal of preemptively targeting anti-American terrorists around the world.

You can get a preview of the argument in his ‘The Eagle Comes Home to Roost: The Historical Origins of the CIA’s Lethal Drone Program’ in Intelligence & National Security 30 (6) (2015) 769-92; you can access a version of that essay, with some of his early essays on the US as what he now calls a ‘post-territorial empire’, via Academia here.

Finally, also forthcoming from Yale, a reflection on War by A.C. Grayling (whose Among the Dead Cities was one of the inspirations for my own work on bombing):

For residents of the twenty-first century, a vision of a future without warfare is almost inconceivable. Though wars are terrible and destructive, they also seem unavoidable. In this original and deeply considered book, A. C. Grayling examines, tests, and challenges the concept of war. He proposes that a deeper, more accurate understanding of war may enable us to reduce its frequency, mitigate its horrors, and lessen the burden of its consequences.

For residents of the twenty-first century, a vision of a future without warfare is almost inconceivable. Though wars are terrible and destructive, they also seem unavoidable. In this original and deeply considered book, A. C. Grayling examines, tests, and challenges the concept of war. He proposes that a deeper, more accurate understanding of war may enable us to reduce its frequency, mitigate its horrors, and lessen the burden of its consequences.

Grayling explores the long, tragic history of war and how warfare has changed in response to technological advances. He probes much-debated theories concerning the causes of war and considers positive changes that may result from war. How might these results be achieved without violence? In a profoundly wise conclusion, the author envisions “just war theory” in new moral terms, taking into account the lessons of World War II and the Holocaust and laying down ethical principles for going to war and for conduct during war.