An excellent article from the unfailing New York Times in a recent edition of the Magazine: Azmat Khan and Anand Gopal on ‘The Uncounted‘, a brilliant, forensic and – crucially – field-based investigation into civilian casualties in the US air war against ISIS:

American military planners go to great lengths to distinguish today’s precision strikes from the air raids of earlier wars, which were carried out with little or no regard for civilian casualties. They describe a target-selection process grounded in meticulously gathered intelligence, technological wizardry, carefully designed bureaucratic hurdles and extraordinary restraint. Intelligence analysts pass along proposed targets to “targeteers,” who study 3-D computer models as they calibrate the angle of attack. A team of lawyers evaluates the plan, and — if all goes well — the process concludes with a strike so precise that it can, in some cases, destroy a room full of enemy fighters and leave the rest of the house intact.

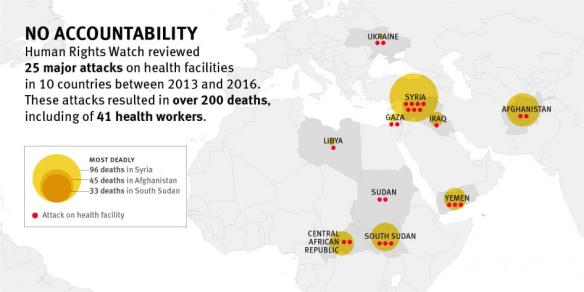

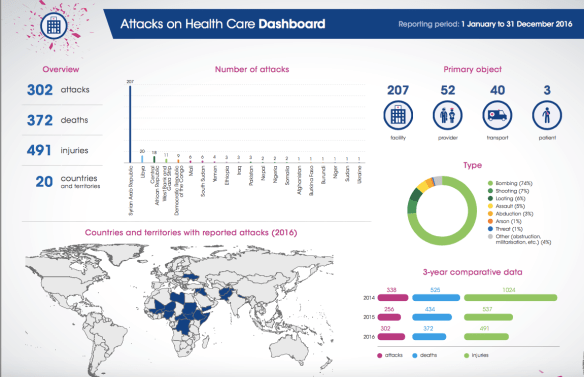

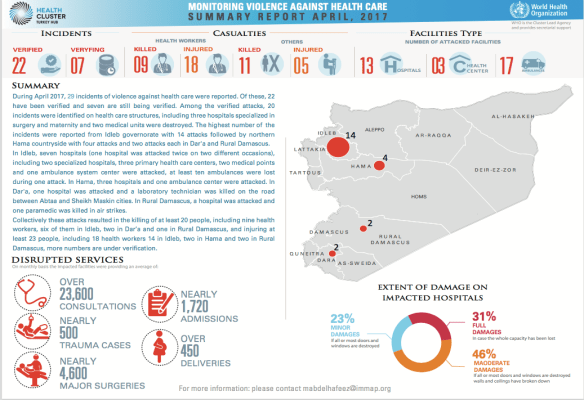

The coalition usually announces an airstrike within a few days of its completion. It also publishes a monthly report assessing allegations of civilian casualties. Those it deems credible are generally explained as unavoidable accidents — a civilian vehicle drives into the target area moments after a bomb is dropped, for example. The coalition reports that since August 2014, it has killed tens of thousands of ISIS fighters and, according to our tally of its monthly summaries, 466 civilians in Iraq.

What Azmat and Anand found on the ground, however, was radically different:

Our own reporting, conducted over 18 months, shows that the air war has been significantly less precise than the coalition claims. Between April 2016 and June 2017, we visited the sites of nearly 150 airstrikes across northern Iraq, not long after ISIS was evicted from them. We toured the wreckage; we interviewed hundreds of witnesses, survivors, family members, intelligence informants and local officials; we photographed bomb fragments, scoured local news sources, identified ISIS targets in the vicinity and mapped the destruction through satellite imagery. We also visited the American air base in Qatar where the coalition directs the air campaign. There, we were given access to the main operations floor and interviewed senior commanders, intelligence officials, legal advisers and civilian-casualty assessment experts. We provided their analysts with the coordinates and date ranges of every airstrike — 103 in all — in three ISIS-controlled areas and examined their responses. The result is the first systematic, ground-based sample of airstrikes in Iraq since this latest military action began in 2014.

We found that one in five of the coalition strikes we identified resulted in civilian death, a rate more than 31 times that acknowledged by the coalition. It is at such a distance from official claims that, in terms of civilian deaths, this may be the least transparent war in recent American history [my emphasis]. Our reporting, moreover, revealed a consistent failure by the coalition to investigate claims properly or to keep records that make it possible to investigate the claims at all. While some of the civilian deaths we documented were a result of proximity to a legitimate ISIS target, many others appear to be the result simply of flawed or outdated intelligence that conflated civilians with combatants. In this system, Iraqis are considered guilty until proved innocent. Those who survive the strikes … remain marked as possible ISIS sympathizers, with no discernible path to clear their names.

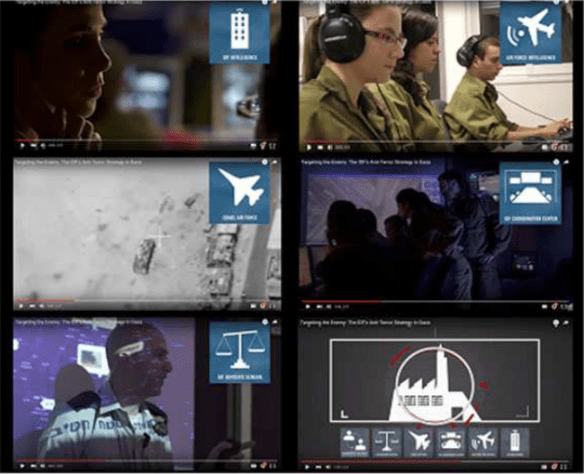

They provide immensely powerful, moving case studies of innocents ‘lost in the wreckage’. They also describe the US Air Force’s targeting process at US Central Command’s Combined Air Operations Center (CAOC) at Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar (the image above shows the Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance Division at the CAOC, which ‘provides a common threat and targeting picture’):

The process seemed staggeringly complex — the wall-to-wall monitors, the soup of acronyms, the army of lawyers — but the impressively choreographed operation was designed to answer two basic questions about each proposed strike: Is the proposed target actually ISIS? And will attacking this ISIS target harm civilians in the vicinity?

As we sat around a long conference table, the officers explained how this works in the best-case scenario, when the coalition has weeks or months to consider a target. Intelligence streams in from partner forces, informants on the ground, electronic surveillance and drone footage. Once the coalition decides a target is ISIS, analysts study the probability that striking it will kill civilians in the vicinity, often by poring over drone footage of patterns of civilian activity. The greater the likelihood of civilian harm, the more mitigating measures the coalition takes. If the target is near an office building, the attack might be rescheduled for nighttime. If the area is crowded, the coalition might adjust its weaponry to limit the blast radius. Sometimes aircraft will even fire a warning shot, allowing people to escape targeted facilities before the strike. An official showed us grainy night-vision footage of this technique in action: Warning shots hit the ground near a shed in Deir al-Zour, Syria, prompting a pair of white silhouettes to flee, one tripping and picking himself back up, as the cross hairs follow.

Once the targeting team establishes the risks, a commander must approve the strike, taking care to ensure that the potential civilian harm is not “excessive relative to the expected military advantage gained,” as Lt. Col. Matthew King, the center’s deputy legal adviser, explained.

After the bombs drop, the pilots and other officials evaluate the strike. Sometimes a civilian vehicle can suddenly appear in the video feed moments before impact. Or, through studying footage of the aftermath, they might detect signs of a civilian presence. Either way, such a report triggers an internal assessment in which the coalition determines, through a review of imagery and testimony from mission personnel, whether the civilian casualty report is credible. If so, the coalition makes refinements to avoid future civilian casualties, they told us, a process that might include reconsidering some bit of intelligence or identifying a flaw in the decision-making process.

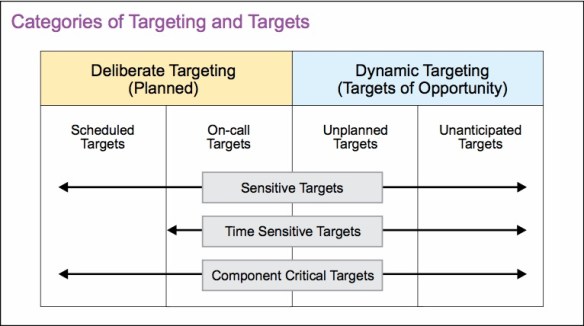

There are two issues here. First, this is indeed the ‘best-case scenario’, and one that very often does not obtain. One of the central vectors of counterinsurgency and counterterrorism is volatility: targets are highly mobile and often the ‘window of opportunity’ is exceedingly narrow. I’ve reproduced this image from the USAF’s own targeting guide before, in relation to my analysis of the targeting cycle for a different US air strike against IS in Iraq in March 2015, but it is equally applicable here:

Second, that ‘window of opportunity’ is usually far from transparent, often frosted and frequently opaque. For what is missing from the official analysis described by Azmat and Anand turns out to be the leitmotif of all remote operations (and there is a vital sense in which all forms of aerial violence are ‘remote’, whether the pilot is 7,000 miles away or 30,000 feet above the target [see for example here]):

Lt. Gen. Jeffrey Harrigian, commander of the United States Air Forces Central Command at Udeid, told us what was missing. “Ground truth, that’s what you’re asking for,” he said. “We see what we see from altitude and pull in from other reports. Your perspective is talking to people on the ground.” He paused, and then offered what he thought it would take to arrive at the truth: “It’s got to be a combination of both.”

The military view, perhaps not surprisingly, is that civilian casualties are unavoidable but rarely intentional:

Supreme precision can reduce civilian casualties to a very small number, but that number will never reach zero. They speak of every one of the acknowledged deaths as tragic but utterly unavoidable.

Azmat and Anand reached a numbingly different conclusion: ‘Not all civilian casualties are unavoidable tragedies; some deaths could be prevented if the coalition recognizes its past failures and changes its operating assumptions accordingly. But in the course of our investigation, we found that it seldom did either.’

Part of the problem, I suspect, is that whenever there is an investigation into reports of civilian casualties that may have been caused by US military operations it must be independent of all other investigations and can make no reference to them in its findings; in other words, as I’ve noted elsewhere, there is no ‘case law’: bizarre but apparently true.

But that is only part of the problem. The two investigators cite multiple intelligence errors (‘In about half of the strikes that killed civilians, we could find no discernible ISIS target nearby. Many of these strikes appear to have been based on poor or outdated intelligence’) and even errors and discrepancies in recording and locating strikes after the event.

It’s worth reading bellingcat‘s analysis here, which also investigates the coalition’s geo-locational reporting and notes that the official videos ‘appear only to showcase the precision and efficiency of coalition bombs and missiles, and rarely show people, let alone victims’. The image above, from CNN, is unusual in showing the collection of the bodies of victims of a US air strike in Mosul, this time in March 2017; the target was a building from which two snipers were firing; more than 100 civilians sheltering there were killed. The executive summary of the subsequent investigation is here – ‘The Target Engagement Authority (TEA) was unaware of and could not have predicted the presence of civilians in the structure prior to the engagement’ – and report from W.J. Hennigan and Molly Hennessy-Fiske is here.

Included in bellingcat’s account is a discussion of a video which the coalition uploaded to YouTube and then deleted; Azmat retrieved and archived it – the video shows a strike on two buildings in Mosul on 20 September 2015 that turned out to be focal to her investigation with Anand:

The video caption identifies the target as a ‘VBIED [car bomb] facility’. But Bellingcat asks:

Was this really a “VBIED network”? Under the original upload, a commenter starting posting that the houses shown were his family’s residence in Mosul.

“I will NEVER forget my innocent and dear cousins who died in this pointless airstrike. Do you really know who these people were? They were innocent and happy family members of mine.”

Days after the strike, Dr Zareena Grewal, a relative living in the US wrote in the New York Times that four family members had died in the strike. On April 2, 2017 – 588 days later – the Coalition finally admitted that it indeed bombed a family home which they confused for an IS headquarters and VBIED facility.

“The case was brought to our attention by the media and we discovered the oversight, relooked [at] the case based on the information provided by the journalist and family, which confirmed the 2015 assessment,” Colonel Joe Scrocca, Director of Public Affairs for the Coalition, told Airwars.

Even though the published strike video actually depicted the killing of a family, it remained – wrongly captioned – on the official Coalition YouTube channel for more than a year.

This is but one, awful example of a much wider problem. The general conclusion reached by Azmat and Anand is so chilling it is worth re-stating:

According to the coalition’s available data, 89 of its more than 14,000 airstrikes in Iraq have resulted in civilian deaths, or about one of every 157 strikes. The rate we found on the ground — one out of every five — is 31 times as high.

One of the houses [shown above] mistakenly identified as a ‘VBIED facility’ in that video belonged to Basim Razzo, and he became a key informant in Azmat and Anand’s investigation; he was subsequently interviewed by Amy Goodman: the transcript is here. She also interviewed Azmat and Anand: that transcript is here. In the course of the conversation Anand makes a point that amply and awfully confirms Christiane Wilke‘s suggestion – in relation to air strikes in Afghanistan – that the burden of recognition, of what in international humanitarian law is defined as ‘distinction’, is tacitly being passed from combatant to civilian: that those in the cross-hairs of the US military are required to perform their civilian status to those watching from afar.

It goes back to this issue of Iraqis having to prove that they are not ISIS, which is the opposite of what we would think. We would think that the coalition would do the work to find out whether somebody is a member of ISIS or not. Essentially, they assume people are ISIS until proven otherwise.

To make matters worse, they have to perform their ‘civilianness’ according to a script recognised and approved by the US military, however misconceived it may be. In the case of one (now iconic) air strike in Afghanistan being an adolescent or adult male, travelling in a group, praying at one of the times prescribed by Islam, and carrying a firearm in a society where that is commonplace was enough for civilians to be judged as hostile by drone crews and attacked from the air with dreadful results (see here and here).

This is stunning investigative journalism, but it’s more than that: the two authors are both at Arizona State University, and they have provided one of the finest examples of critical, probing and accessible scholarship I have ever read.