This is the fourth in a series of posts on Grégoire Chamayou‘s Théorie du drone.

7: Counter-insurgency from the air

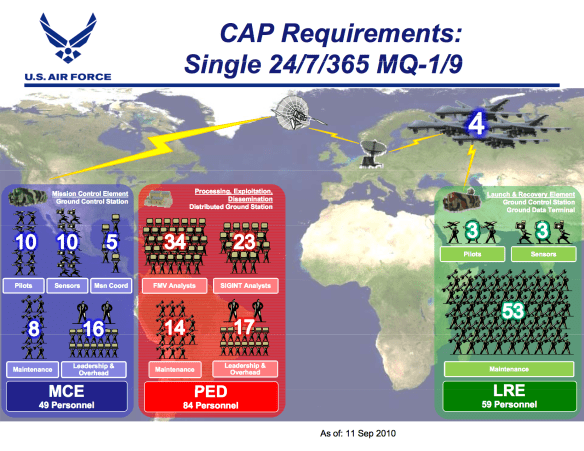

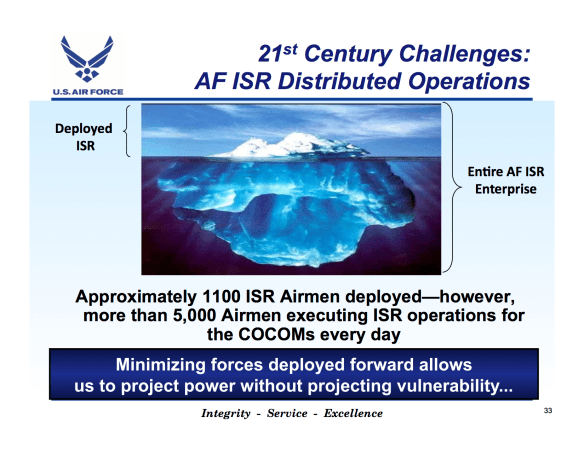

The focus of the new US Army /US Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Manual FM 3-24 that was issued in 2006 was, naturally enough, on ground operations in which the Army and the Marine Corps would take the lead. To the anger of many Air Force officers, air operations were relegated to a supporting role outlined in the last appendix, the last five pages of 335, which acknowledged the contribution of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) from ‘air- mounted collection platforms’ and (in certain circumstances) the ‘enormous value’ of ‘precision air attacks’.

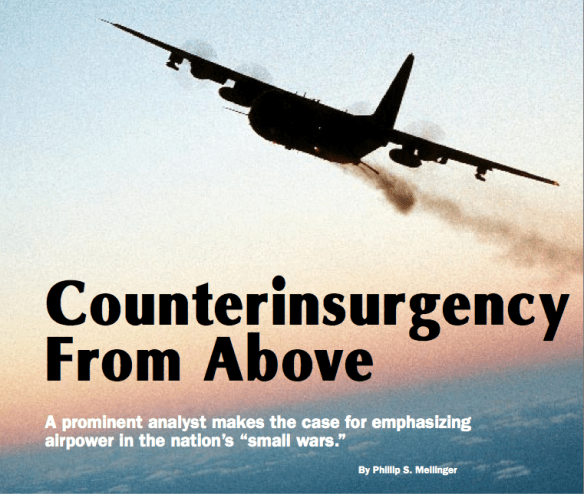

And yet in practice, as Chamayou argues, the balance was already being reversed; the incorporation of drones into counterinsurgency (COIN) was soon so advanced that there were calls (from air power advocates) for the promulgation of an official doctrine reflecting the new intrinsically three-dimensional reality. So – to take the example Chamayou gives – Phillip Meilinger, a retired command pilot and former Dean of the School of Advanced Airpower Studies at the USAF’s Air University at Maxwell AFB, complained that the Field Manual had already been overtaken by events:

The role for airpower in COIN is generally seen as providing airlift, ISR capabilities, and precision strike. This outdated paradigm is too nar- rowly focused and relegates airpower to the support role while ground forces perform the “real” work. Worse, marginalizing airpower keeps it in support of ground-centric strategies that have proved unsuccessful.

He called for the Pentagon to

‘re-examine the paradigm that was so successful in Bosnia, Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq. That was the use of air and space power, combined with [Special Operations Forces], indigenous ground forces, and overwhelming ISR. Given the outstanding results already demonstrated, an air-centric joint COIN model should be one of the first options for America’s military and political leaders.’

As the image heading his article makes clear, Meilinger – a gifted military historian – was not limiting the role of airpower to drones; far from it. But his repeated references to the Air Force’s ‘more sophisticated and effective sensor aircraft and satellites’ signalled their indispensable importance in the transformation of counterinsurgency from a ground-centric to an air-centric model.

A similar salvo was fired at more or less the same time by Charles Dunlap, Deputy Judge Advocate General for the USAF, who castigated FM 3-24 for conceiving air power ‘as aerial artillery’ whose weapons were ‘somehow more inaccurate than other kinds of fires.’

A similar salvo was fired at more or less the same time by Charles Dunlap, Deputy Judge Advocate General for the USAF, who castigated FM 3-24 for conceiving air power ‘as aerial artillery’ whose weapons were ‘somehow more inaccurate than other kinds of fires.’

‘In perhaps no other area has the manual been proven more wrong by the events of 2007…. [T]he profound changes in airpower’s capabilities have so increased its utility that it is now often the weapon of first recourse in COIN operations, even in urban environments.’

Dunlap was quick to say that this myopia wasn’t the result of inter-service rivalry (‘parochialism’):

‘Rather, FM 3-24 draws many of its lessons from counterinsurgency operations dating from the 1950s through the 1970s. While this approach is remarkably effective in many respects, it inherently undervalues airpower. The revolutions in airpower capabilities that would prove so effective during 2007 were unavailable to counterinsurgents in earlier eras.’

Those ‘revolutions’ – what Dunlap identified as ‘the precision and persistence revolutions’ – placed armed drones at the leading edge of counterinsurgency and, as Chamayou glosses these arguments, consigned previous objections to the dustbin of history.

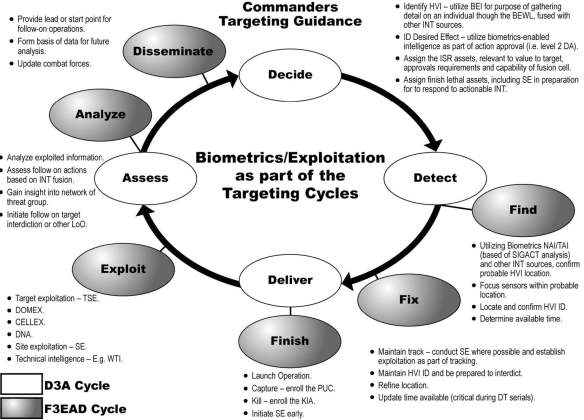

Recalling my post yesterday about ‘pattern of life’ analysis, Dunlap argued that ‘visual observations have a grammar all their own’, and he cited with approval this paragraph from journalist Mark Benjamin‘s ‘Killing “Bubba” from the skies’:

‘The Air Force recently watched one man in Iraq for more than five weeks, carefully recording his habits—where he lives, works, and worships, and whom he meets . The military may decide to have such a man arrested, or to do nothing at all. Or, at any moment they could decide to blow him to smithereens.’

It’s a revealing essay that accords closely with Chamayou’s central thesis: Benjamin reported that, from the Combined Air Operations Center in Qatar, ‘they are stalking prey’ and that the US Air Force had turned the art of searching for individuals into a science.

But Dunlap cooly added: ‘The last statement may be more insightful than perhaps even Benjamin realized.’ For it was not only a matter of killing, ‘blowing a man to smithereens’, and what Dunlap had in mind was not only persistent presence but also persistent threat: the ability to ‘dislocate the psychology of the insurgents’ who now never knew where or when they might be attacked.

For this reason Chamayou suggests that the drone effects a sort of détournement on the strategies and weapons of the insurgent-terrorist – the skirmish and the ambush, the IED and the suicide bomb – to become what he calls, through this radical reversal, ‘the weapon of State terrorism’. Its short-lived engagements happen without warning and target individuals without compunction.

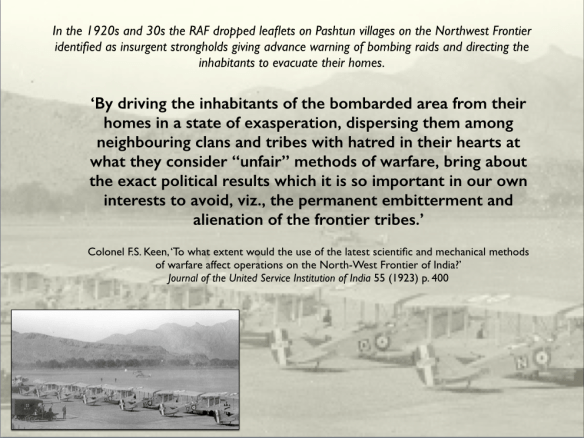

And yet, for all its technological sophistication, Chamayou insists that this is not a new strategy. Military historians ought to look further back, he suggests, to the policies of colonial ‘air control’ developed in the inter-war period (the image below shows a bomb dropped by the RAF on Sulaimaniyah in Iraq on 27 May 1924: more here). He develops this argument in a later chapter, where he describes the drone as ‘the weapon of an amnesiac post-colonial violence’ (p. 136): a postcolonialism that has forgotten – or suppressed – its own wretched history.

Indeed it has. The twenty-first century version of counterinsurgency has made much of the iconic, inspirational figure of ‘Lawrence of Arabia’. But as I’ve argued in ‘DisOrdering the Orient’ (DOWNLOADS tab):

‘… long before he resigned his Army commission and re-enlisted in the Royal Air Force as Aircraftsman Ross, [Lawrence] had been drawn to the wide open spaces of the sky as well as those of the desert. Patrick Deer suggests that in Lawrence’s personal mythology ‘air control in the Middle East offered a redemptive postscript to his role in the Arab Revolt of 1916-18’. He imagined the Arab Revolt ‘as a kind of modernist vortex,’ Deer argues, fluid and dynamic, ‘without front or back,’ and in Seven Pillars he recommended ‘not disclosing ourselves till we attack.’ To Lawrence, and to many others at the time, the intimation of a nomadic future war gave air power a special significance. ‘What the Arabs did yesterday,’ he wrote, ‘the Air Forces may do tomorrow – yet more swiftly.’ As Priya Satia has shown, this rested not only on a military Orientalism that distinguished different ways of war but also on a cultural Orientalism that represented bombing as signally appropriate to the people of these lands. This was, minimally, about intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance. ‘According to this perverse logic’, Satia explains, ‘the RAF’s successful persecution of a village testified to their intimacy with the people on the ground, without which they would not have been able to strike it accurately.’ More than this, however, ‘the claim to empathy ultimately underwrote the entire air control system with its authoritative reassurances that bombardment was a tactic that would be respected and expected in this unique land.’ From this perspective, Satia continues, Arabs saw bombing as ‘pulling the strings of fate from the sky.’ They understood it ‘not as punishment,’ Lawrence informed his readers, ‘but as misfortune from heaven striking the community.’ And if women and children were killed in the process that was supposedly of little consequence to them: what mattered were the deaths of ‘the really important men.’’

As far as I know, Lawrence has not been invoked by any of the contemporary advocates of airpower in counterinsurgency – though he has been called ‘Lawrence of Airpower‘ – but many of these formulations and their successors, translated into an ostensibly more scientific vocabulary, reappear in contemporary debates about the deployment of drones in counterinsurgency.

In fact, Meilinger had conceded the relevance of these historical parallels. ‘It would be useful to revisit the “air control” operations employed by the Royal Air Force in the Middle East in the 1920s and 1930s,’ he wrote. ‘These operations were not always successful in objective military terms, but they were unusually successful in political terms, in part because they carried a low cost in both financial and casualty terms’ (my emphasis).

That is an extraordinary sentence, although Chamayou doesn’t quote it, because what is missing from the air power advocates’ view (so Chamayou argues) is – precisely – an apprehension of the politics of counterinsurgency in general and air strikes in particular. Indeed, when the imaginary conjured up by Lawrence and his successors reappears in contemporary debates it is entered on both sides of the ledger: not only as economical and effective but also as cowardly and counter-productive. Here is Colonel Keen, complaining about the bombing of Pashtun villages on the North West Frontier in 1923:

‘By driving the inhabitants of the bombarded area from their homes in a state of exasperation, dispersing them among neighbouring clans and tribes with hatred in their hearts at what they consider ‘‘unfair’’ methods of warfare … [these attacks] bring about the exact political results which it is so important in our own interests to avoid, viz., the permanent embitterment and alienation of the frontier tribes.’

Both Chamayou and I cite this passage, and you can find more about the colonial bombing of Waziristan in a previous post (scroll down).

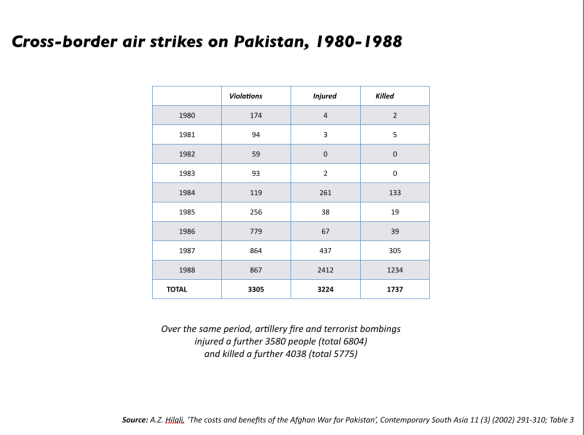

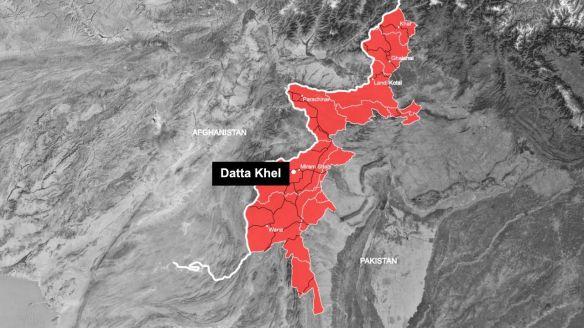

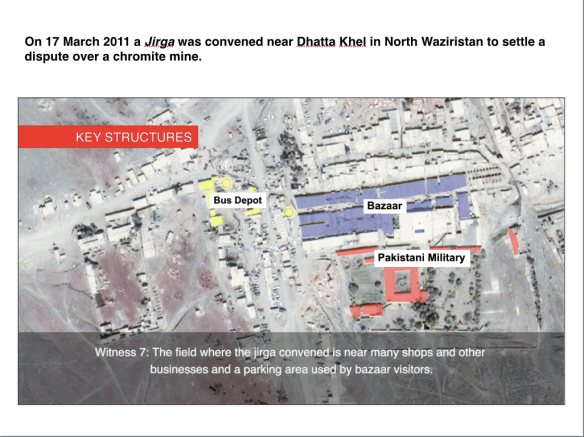

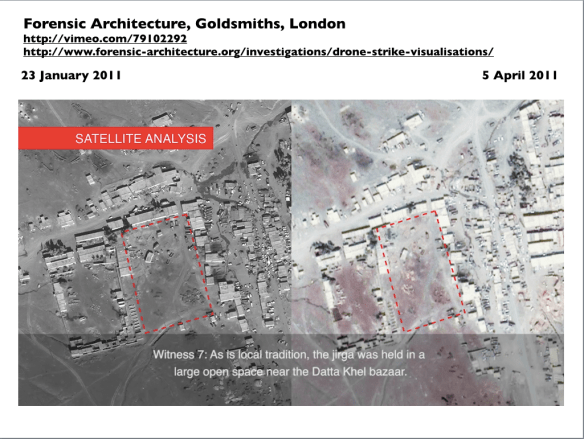

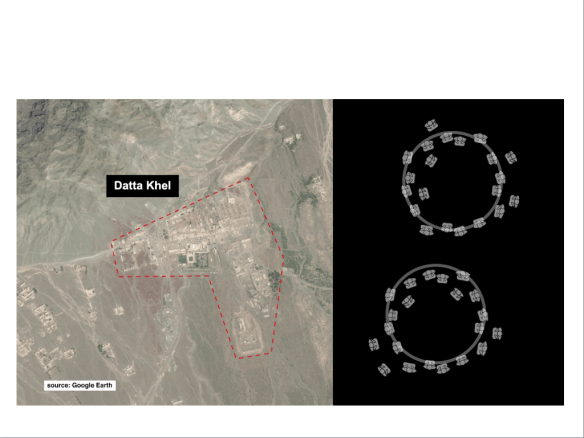

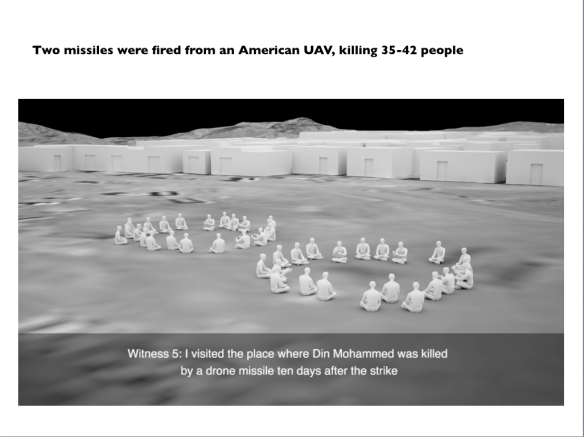

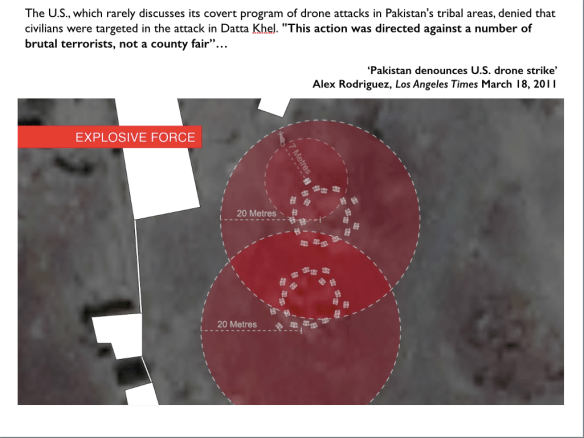

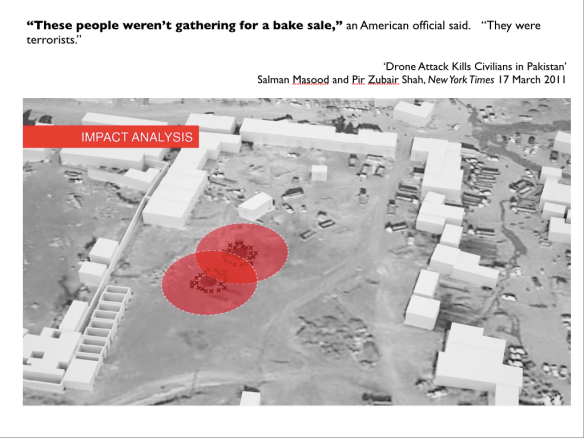

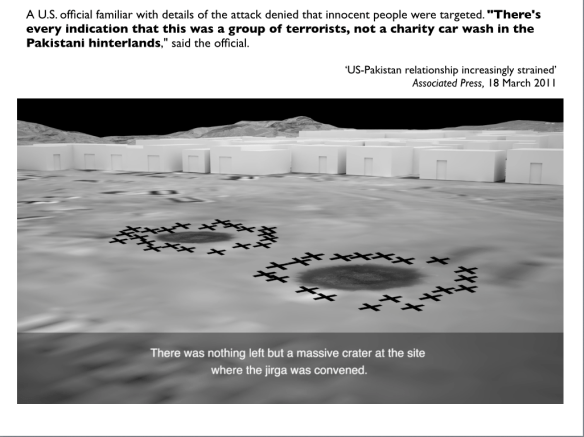

This sentiment reappeared in different form in the critique of drone strikes in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas – the same region described by Keen – published by David Kilcullen and Andrew Exum in the New York Times in 2009, ‘Death from above, Outrage down below‘. Their core argument was that the campaign was making the cardinal mistake of ‘personalizing’ the struggle against al-Qaeda and the Taliban – going after individuals – while causing considerable civilian casualties: ‘every one of these dead noncombatants represents an alienated family, a new desire for revenge, and more recruits for a militant movement that has grown exponentially even as drone strikes have increased.’

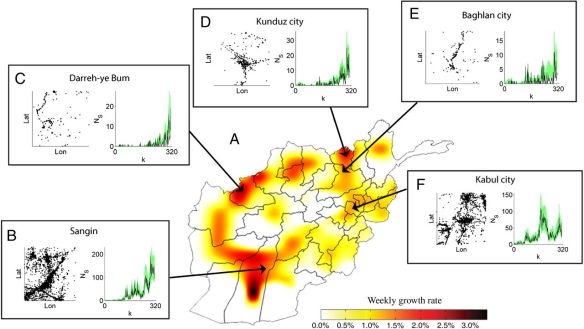

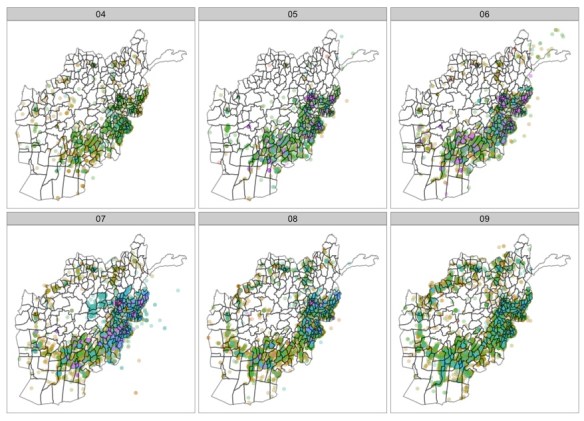

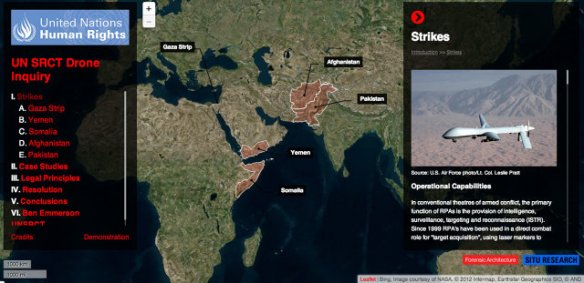

Estimates of combatant and civilian casualties remain contentious, of course, including those used by Kilcullen and Exum; Chamayou doesn’t discuss this in any detail, but most sources (including the Bureau of Investigate Journalism) suggest that civilian casualties in Pakistan have fallen from their peak in 2009-10. Others have argued that drone strikes are more effective than their critics claim. Their confidence typically rests on a combination of assertion and anecdote, but a recent quantitative study by Patrick Johnston and Anoop Sarbahi (from which I’ve borrowed the map below) purports to show that, contrary to Kilcullen and Exum’s original claim, US drone strikes between January 2007 and September 2011 reduced the incidence of militant activity in the FATA.

I mention these qualifications neither to adjudicate them nor to blunt Chamayou’s argument: simply to note that the situation is far from static or settled. Chamayou uses the Kilcullen-Exum critique, in conjunction with Kilcullen’s other, more extended contributions, to leverage two linked claims:

(1) counterinsurgency is a politico-military strategy that depends, for its effectiveness, on a sustained presence amongst a population: a politics of verticality (described in my previous post) cannot substitute for, and usually confounds, a properly population-centric campaign, which can only be won on the ground.

(2) the ‘dronisation’ of US military operations signals a shift away from counterinsurgency and towards counter-terrorism, which is a police-security strategy that prioritises an individual-centric campaign.

Chamayou owes the distinction to Kilcullen [‘Countering global insurgency’, Journal of strategic studies 28 (2005) 597-617]:

‘Under this [counter-terrorism] paradigm … terrorists are seen as unrepresentative aberrant individuals, misfits within society. Partly because they are unrepresentative, partly to discourage emulation, ‘we do not negotiate with terrorists’. Terrorists are criminals, whose methods and objectives are both unacceptable. They use violence partly to shock and influence populations and governments, but also because they are psychologically or morally flawed (‘evil’) individuals. In this paradigm, terrorism is primarily a law enforcement problem, and we therefore adopt a case-based approach where the key objective is to apprehend the perpetrators of terrorist attacks…

‘The insurgency paradigm is different. Under this approach, insurgents are regarded as representative of deeper issues or grievances within society. We seek to defeat insurgents through ‘winning the hearts and minds’ of the population, a process that involves compromise and negotiation. We regard insurgents’ methods as unacceptable, but their grievances are often seen as legitimate, provided they are pursued peacefully… We see insurgents as using violence within an integrated politico-military strategy, rather than as psychopaths. In this paradigm, insurgency is a whole-of-government problem rather than a military or law enforce- ment issue. Based on this, we adopt a strategy-based approach to counterinsurgency, where the objective is to defeat the insurgent’s strategy, rather than to ‘apprehend the perpetrators’ of specific acts.’

in Chamayou’s terms, ‘manhunting by drones’ represents the triumph, at once doctrinal and practical, of counter-terrorism over counterinsurgency. In this optic, a space of representation substitutes for lived space: ‘The body count, the list of hunting trophies, substitutes for the strategic evaluation of the political effects of military violence. Success is turned into statistics. Their evaluation is disconnected from effects on the ground.’

It’s an engaging argument, but I think it’s over-stated for several reasons.

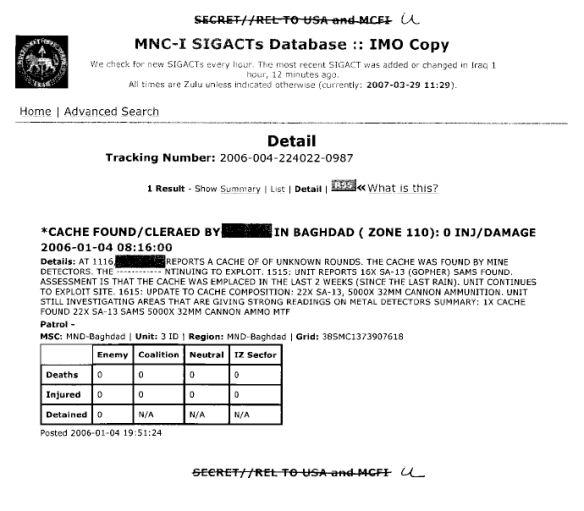

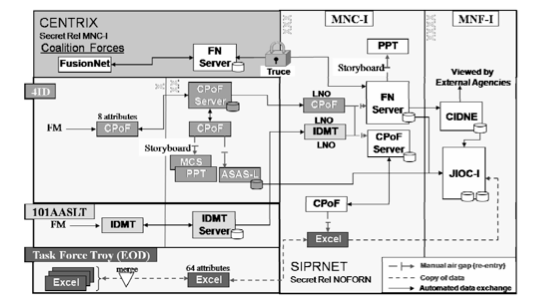

First, contemporary counterinsurgency clearly has not ceded the statistical battleground to anyone. Under David Petraeus in particular, cascades of PowerPoint slides sluiced a tidal wave of metrics over military and public audiences, and these too were often disconnected from events on the ground. As I showed in “Seeing Red” (DOWNLOADS tab), for example, at the height of the violence in Baghdad military briefers preferred the virtual-cartographic to the visceral-physical city, ‘walking’ reporters through maps of the capital because, for all their upbeat assessments, it was far too dangerous to walk them through the real city that lay beyond the Green Zone. And so far it has proved impossible to obtain any figures of fatalities from drone strikes in the FATA from Obama’s otherwise garrulous ‘off-the-record’ (and, remarkably, never prosecuted) officials.

Second, contemporary counterinsurgency is not only about deploying ‘soft power’ and exploiting the humanitarian-military nexus; this is a one-sided view. Kilcullen himself conceded that ‘there’s always a lot of killing, one way or another’, in counterinsurgency, but in the wake of the nightmare that was Abu Ghraib the publicity campaign that surrounded the release of FM 3-24 directed attention to ‘hearts and minds’ – to a kinder, gentler, culturally-informed and compassionate military – rather than to bullets and bombs. But as Petraeus reminded Noah Schachtman in November 2007, the manual

‘doesn’t say that the best weapons don’t shoot. It says sometimes the best weapons don’t shoot. Sometimes the best weapons do shoot.”

As I showed in “The rush to the intimate” (DOWNLOADS tab), more often than one might think. Chamayou is perfectly correct to say that ‘drones are excellent at crushing bodies from a distance, but they are perfectly inappropriate for winning “hearts and minds”‘: but counterinsurgency, even in its supposedly radically new form, involves both.

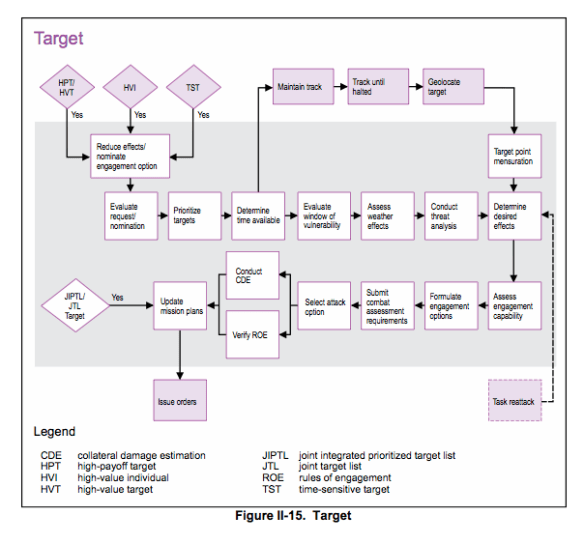

Third, for that very reason counterinsurgency has continued to incorporate air power into its operations, and ground troops and commanders in Afghanistan continue to clamour for Predators and Reapers to provide close air support. In October 2009 the Joint Chiefs of Staff issued Joint Publication 3-24 on Counterinsurgency Operations, which was far more positive about air power than the Field Manual three years earlier:

‘Video downlink and datalink technology have revolutionized real-time air to ground employment allowing air assets to seamlessly integrate into and support the ground commander’s scheme of maneuver. Armed overwatch missions provide ground forces with the critical situational awareness, flexibility, and immediate fire support necessary to succeed in the dynamic COIN environment.’

Fourth, later modern war is intrinsically hybrid, and military operations under its sign are likely to involve an unstable and often contradictory mix of counterinsurgency and counter-terrorism. Writing a year or so into Obama’s first term, Colleen Bell and Brad Evans [in ‘Terrorism to insurgency: Mapping the post-intervention security terrain’, Journal of intervention and statebuilding 4 (4) (2010) 371-390] described a reverse movement from counter-terrorism to counterinsurgency in Afghanistan:

‘Counterterrorist interventionism has, until relatively recently, been principally rooted in an exterminatory logic that demands a sovereign commitment to the violent excision of enemies. The shift towards the problem of insurgency, however, is more expansive. It demonstrates a strategic focus on political opposition as embedded within besieged, illiberal and underdeveloped populations…. [The] focus on insurgency in terms of population represents a break from the preoccupation with terrorism as a form of incalculable danger to the mobilization of a different rationality of risk, that of insurance, which seeks to govern the future on the basis of the collective probabilities emanating from within host societies today.’

They treat this as a transformation of what Chamayou would call the ‘logics’ of intervention: from ‘a conventional struggle to eliminate adversaries’ to a ‘productive reconstitution of the life of a population’ (which requires ‘marking out what qualities the “good” life must possess, whilst in the process positively rendering dangerous all “other” life which does not comply with the productive remit). In other words (their words), a switch from sovereign power to bio-power. I have my reservations about the theoretical argument, but in any case the transformation was far from stable or straightforward. In December 2009 Obama committed thousands of extra ground troops as part of a revitalized counterinsurgency campaign in Afghanistan; they were supported by a continued increase in drone operations. And Obama had also authorised a dramatic increase in CIA-directed drone strikes in Pakistan. But in June 2011 he announced the withdrawal of those additional troops: as Fred Kaplan puts in The insurgents, ‘pulling the plug on COIN.’ All of this va-et-vient was, as Kaplan shows in exquisite detail, more than a philosophico-logical affair: it was also profoundly political, and included considerations of domestic US politics, concerns over the Afghan state in general and the re-election of Hamid Karzai in particular, and no doubt calculations of advantage within the US military. In short, while Chamayou is surely right to accentuate the politics of military violence this is not confined to the ‘inside’ of counterinsurgency – COIN as ‘applied social work’, as Kilcullen once described it – because politics also provides one of its activating armatures. (I’ve discussed Kaplan’s view of drone strikes and what he sees as an emerging imaginary of ‘the world as free-fire zone’ here).

They treat this as a transformation of what Chamayou would call the ‘logics’ of intervention: from ‘a conventional struggle to eliminate adversaries’ to a ‘productive reconstitution of the life of a population’ (which requires ‘marking out what qualities the “good” life must possess, whilst in the process positively rendering dangerous all “other” life which does not comply with the productive remit). In other words (their words), a switch from sovereign power to bio-power. I have my reservations about the theoretical argument, but in any case the transformation was far from stable or straightforward. In December 2009 Obama committed thousands of extra ground troops as part of a revitalized counterinsurgency campaign in Afghanistan; they were supported by a continued increase in drone operations. And Obama had also authorised a dramatic increase in CIA-directed drone strikes in Pakistan. But in June 2011 he announced the withdrawal of those additional troops: as Fred Kaplan puts in The insurgents, ‘pulling the plug on COIN.’ All of this va-et-vient was, as Kaplan shows in exquisite detail, more than a philosophico-logical affair: it was also profoundly political, and included considerations of domestic US politics, concerns over the Afghan state in general and the re-election of Hamid Karzai in particular, and no doubt calculations of advantage within the US military. In short, while Chamayou is surely right to accentuate the politics of military violence this is not confined to the ‘inside’ of counterinsurgency – COIN as ‘applied social work’, as Kilcullen once described it – because politics also provides one of its activating armatures. (I’ve discussed Kaplan’s view of drone strikes and what he sees as an emerging imaginary of ‘the world as free-fire zone’ here).

For all that, Chamayou’s dissection of the ‘reverse logics’ of these particular forms of counterinsurgency and counter-terrorism is analytically helpful, and adds another dimension to his argument about the transformation of war from battlefields to hunting grounds and from armies to individuals. He insists that the commitment to targeted killing (by drone or, I would add, Special Forces) is a commitment to ‘an infinite eradicationism’ in which it becomes impossible to kill leaders (‘High Value Targets’) faster than they can be replaced. In his vivid image, the hydra constantly regenerates itself as a direct response to the very strikes that seek to decapitate it.

‘Advocates for the drone as the privileged weapon against terrorism promise a war without loss or defeat. They fail to note that this will also be war without victory’ (p. 108).

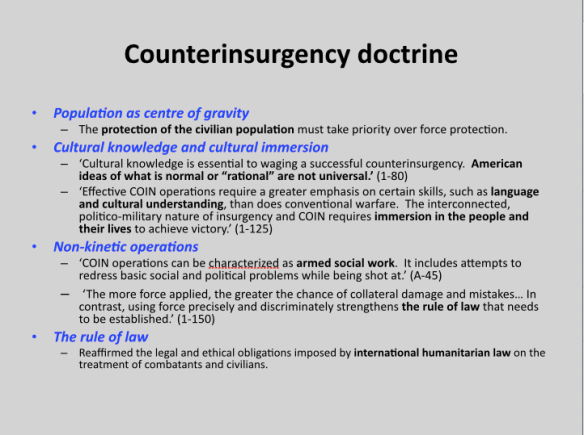

When the US Army and Marine Corps issued their revised Field Manual 3-24 on Counterinsurgency in December 2006 there was an extraordinary public fanfare: a round of high-profile media appearances by some of its architects (you can watch John Nagl with Jon Stewart here) and, even though you could download the Manual for free – there were two million downloads in the first two months – the University of Chicago Press rushed out a paperback edition that hit the best-seller lists. This was all to advertise counterinsurgency as what David Petraeus called ‘the graduate level of war’ and to inaugurate what I called, in ‘The rush to the intimate’ (DOWNLOADS tab), the US military’s ‘cultural turn’. And as the media campaign made clear, it was also about the production of a public that would rally behind the new strategy to be put to work in Iraq. The message was that the military had put the horrors of Abu Ghraib behind it – which were in any case artfully blamed on ‘rotten apples’ rather than the political-military manufacturers of the barrel that contained them – and was now marching beneath the banner of a kinder, gentler and above all smarter war (see my summary slide below).

When the US Army and Marine Corps issued their revised Field Manual 3-24 on Counterinsurgency in December 2006 there was an extraordinary public fanfare: a round of high-profile media appearances by some of its architects (you can watch John Nagl with Jon Stewart here) and, even though you could download the Manual for free – there were two million downloads in the first two months – the University of Chicago Press rushed out a paperback edition that hit the best-seller lists. This was all to advertise counterinsurgency as what David Petraeus called ‘the graduate level of war’ and to inaugurate what I called, in ‘The rush to the intimate’ (DOWNLOADS tab), the US military’s ‘cultural turn’. And as the media campaign made clear, it was also about the production of a public that would rally behind the new strategy to be put to work in Iraq. The message was that the military had put the horrors of Abu Ghraib behind it – which were in any case artfully blamed on ‘rotten apples’ rather than the political-military manufacturers of the barrel that contained them – and was now marching beneath the banner of a kinder, gentler and above all smarter war (see my summary slide below). The debate grumbled on, and many insiders insisted that COIN was dead and buried, interred in the killing fields of Afghanistan. But a revised version of the doctrine has now been issued. It was trailed by the Joint Publication 3-24 on Counterinsurgency last December (issued by the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force and – interestingly – the Coastguard Service), which you can download here (for an early review, see Robert Lamb and Brooke Shawn‘s ‘Is revised COIN manual backed by political will? here). But the new Field Manual has been comprehensively re-written and even re-titled: Insurgencies and countering insurgencies, which you can download here.

The debate grumbled on, and many insiders insisted that COIN was dead and buried, interred in the killing fields of Afghanistan. But a revised version of the doctrine has now been issued. It was trailed by the Joint Publication 3-24 on Counterinsurgency last December (issued by the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force and – interestingly – the Coastguard Service), which you can download here (for an early review, see Robert Lamb and Brooke Shawn‘s ‘Is revised COIN manual backed by political will? here). But the new Field Manual has been comprehensively re-written and even re-titled: Insurgencies and countering insurgencies, which you can download here.