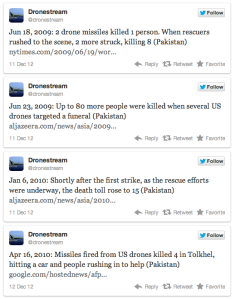

I’m speaking about Drone strikes and the matrix of violence in Pakistan at a conference in Vancouver at the week-end – a presentation which will form part of The everywhere war – and to set some of the parameters I’ve been revisiting the changing geography of air strikes in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas. It’s a formidably difficult question given the extraordinary dangers facing journalists, Pakistani or foreign, seeking to report from the FATA: for an incisive discussion of the media landscape inside the FATA see Sadaf Baig‘s Reporting from the frontlines.

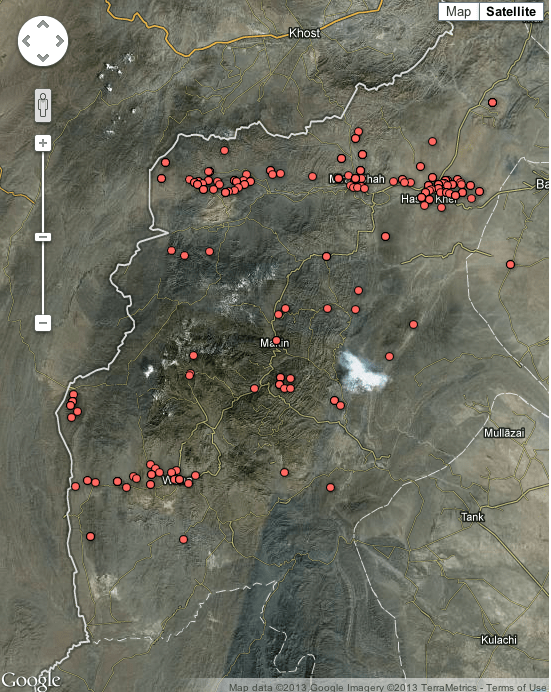

In my view, the most thorough if necessarily imperfect tabulations of US-directed strikes are those provided by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism. There have been several attempts to map this database, including the Bureau’s own use of Google maps (see below and here; but be careful: zooming in is a product of the digital platform and will give a misleading sense of the resolution level of the data).

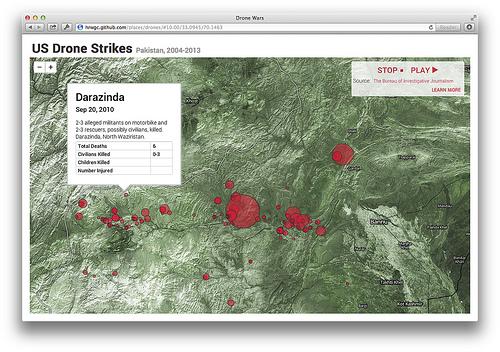

One of the most thoughtful (and dynamic) representations comes from Chris Herwig. He described the technical basis of his mapping over at MapBox here, and you can visit his microsite here. Go here to see the animation running (with annotations).

Chris’s project has also been featured on PBS here, where he also responds to several criticisms of the data and his visualizations.

Over at Slate, Chris Kirk has produced an interactive that tries to show the maximum number of estimated casualties from each strike, but the data are drawn from the New America Foundation database which has been criticised for underestimating casualties; one (to October 2012) version is here, and another (to February 2013), using a different cartographic design, is here. More generally, Forensic Architecture‘s Unmanned Aerial Violence team is working to produce an online visualization of drone strikes not only over Pakistan but also over Afghanistan,Yemen, Somalia and Palestine. but it’s not yet operational).

But the problem doesn’t end with the cartographic piercing of the veil of semi-secrecy the White House, the CIA and JSOC cast over their remote operations, though I’ve noted before how their collective teasing of American journalists over the legal and administrative protocols they supposedly follow – especially the so-called “disposition matrix” – works to (mis)direct attention towards Washington and away from the sites that Chris and others have struggled to map.

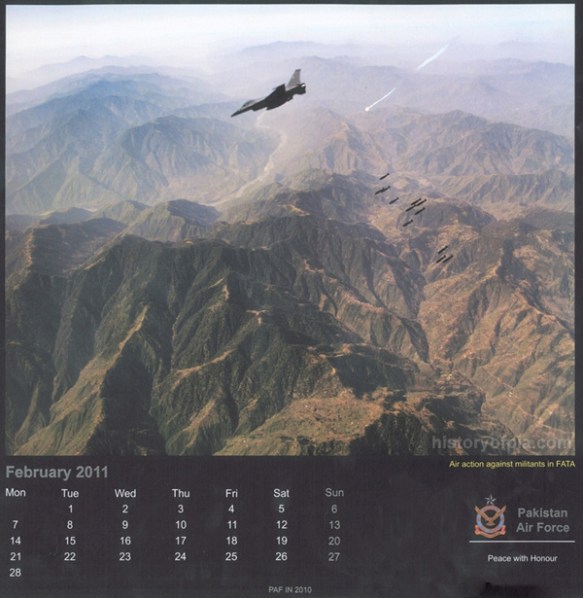

I say this because the US is not the only state carrying out air strikes in the region. Soon after 9/11 and the US-led invasion of Afghanistan, largely in response to pressure from Washington, the Pakistan military moved into the FATA. According to Zahid Ali Khan, Pakistan’s Frontier Corps was deployed in December 2001, but by May 2002 it was decided that a much heavier hand was needed and the Pakistan Army was ordered into the borderlands for the first time in the nation’s history. Local people requested that military operations be limited to ground forces, but by 2004 this agreement was in shreds and – as the image below shows – ever since the Pakistan Air Force has made no secret of its continuing air strikes on the FATA.

Again, there is no public tabulation, but the American Enterprise Institute‘s Critical Threats daily Pakistan Security Brief – I know, I know, it’s a neoconservative think-tank – culls this (needless to say, approving) record from reports in Pakistan media in the first two months of this year alone:

25 February PAF kills 10 TTP militants in Tirah [Kurram/Khyber, FATA]

21 February PAF bombs militants in Orakzai [NWF Province] killing 29

19-20 February PAF jets bomb TTP hideouts in Orakzai

11 February PAF jets kill 8 militants in the Tirah Valley

8 February Jets kill 9 militants in Orakzai

7 February PAF targets militants in Orakzai

6 February Jets kill 8 in Orakzai

30 January PAF kills 23 militants in Tirah Valley and 8 in Orakzai agency

28 January Pakistani jets bomb militants in Orakzai

4 January Gunships kill 3, injure more in North Waziristan retaliation

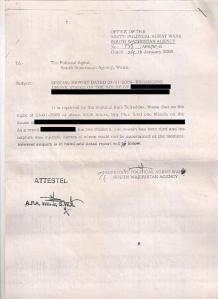

It’s a bare bones summary, clearly, and I suspect the readiness of the AEI to trust local media to report PAF strikes is in stark contrast to their attitude to local reports of US drone strikes. I’ve also deliberately retained the original phrasing: conspicuously, there is no record of civilian casualties. Like the United States, Pakistan routinely plays these down or denies them altogether. Here, for example, is a typical report via the Long War Journal on 25 March 2010:

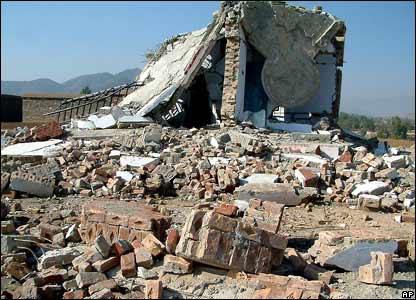

‘Pakistani fighter-bombers struck a series of targets in the Mamuzai region in [Orakzai] today. Sixty-one Taliban fighters were killed, Pakistani intelligence officials told The Associated Press. The military claimed that no civilians were killed in the attacks. The targets included a madrassa, a mosque, and a seminary run by the Tablighi Jamaat. Pakistani officials said that Taliban leaders were meeting at the Tablighi seminary.’

It’s unlikely that civilians were unscathed. For the first four years at least the accuracy of the Air Force’s strikes was compromised by what Irfan Ahmad described as its ‘lack of real time electronic intelligence and inferior technical means for command, control and communications’, by deficiencies in the targeting pods used by the PAF’s ageing F-16 aircraft, and by the use of laser-guided missiles whose precision was reduced by clouds or poor visibility. From 2008 new electro-optical targeting pods and sensors were being retrofitted and new ground and air capabilities for image exploitation put in place. In 2009 the Air Force was also the launch customer for the Anglo-Italian Falco reconnaissance drone (see below), which is now co-produced in Pakistan; five systems were soon in use over the FATA, each comprising four aircraft with one held in reserve, and the Air Force was already anticipating arming them ‘with the most modern and lethal payloads’. More recently, the PAF has upgraded its F-16 fleet with new Block 52 versions and installed advanced avionics. Throughout this period, as the military offensive periodically intensified, hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions of people were displaced from the borderlands.

It’s difficult to provide a detailed accounting of the air strikes, but in a rare admission former Air Chief Marshall Rao Qamar Suleiman claimed that the Pakistan Air Force carried out 5,000 strike sorties and dropped 11,600 bombs on 4,600 targets in the FATA between May 2008 and November 2011. Unlike US air strikes in the region, PAF strikes are rarely ‘stand-alone’ affairs but are co-ordinated with ground forces (which is also the case with most drone strikes in Afghanistan, which operate in close concert with troops and conventional strike aircraft).

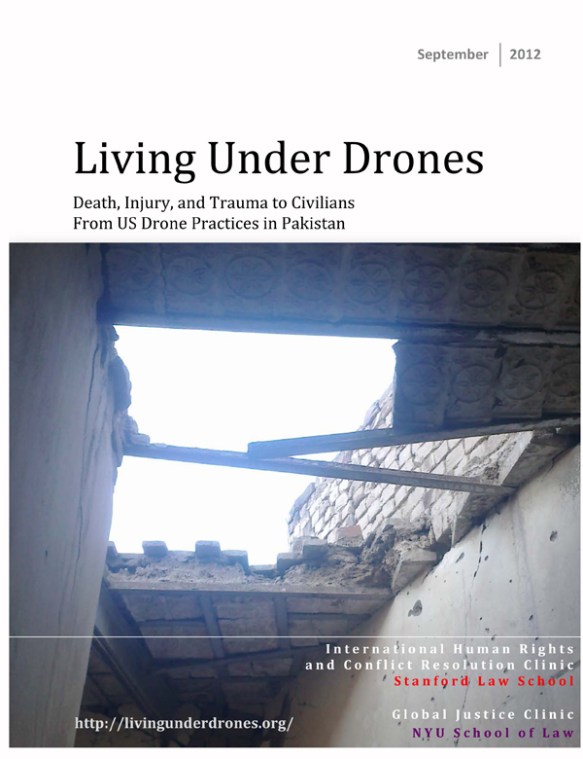

My object is recording all this is (I hope obviously) emphatically not to say that it is perfectly acceptable for the US to launch air strikes in the FATA because Pakistan is doing the same. Rather, the co-existence of the two air campaigns explains, in part, how it is possible for each party to accuse the other of carrying out an attack, as reported earlier this month. More importantly, it also emphasises the ever-present horizon of danger within which the inhabitants of the borderlands are forced to live. They are not only Living under drones.

The same point was sharpened by CIVIC – now the Center for Civilians in Conflict – in their (I think vital) report Civilian harm and conflict in North West Pakistan, published in October 2010. That report also details the violence meted out to civilians by militant groups in the region; for a detailed survey of the political geography of the borderlands, see Brian Fishman‘s The Battle for Pakistan: militancy and conflict across the FATA and NWFP, produced for the New America Foundation in 2010; there’s also much to think about in Daanish Mustafa and Katherine Brown, ‘Spaces of performative politics and terror in Pakistan‘, and in the same authors’ ‘The Taliban, Public Space and terror in Pakistan‘.

The existence of the two air campaigns also shows that the FATA are produced as a space of exception not only through Washington’s strenuous juggling with the Authorisation to Use Military Force and with international law (to validate the extension of its ‘global battlefield’) – whether it does so with or without Islamabad’s covert consent remains an open question – but also through Islamabad’s continued determination to treat the borderlands as legally anomalous territories for its own assertion of military violence.

The last is a doubled colonial legacy. Not only is the legal geography that structures the FATA’s relations with the Pakistani state a relict from Britain’s imperial decision to treat them as a space to be ‘excepted from state and society for the purposes of war’, as Ian Shaw and Majed Akhter put it in Antipode recently.

The last is a doubled colonial legacy. Not only is the legal geography that structures the FATA’s relations with the Pakistani state a relict from Britain’s imperial decision to treat them as a space to be ‘excepted from state and society for the purposes of war’, as Ian Shaw and Majed Akhter put it in Antipode recently.

So too is the decision to continue to use the FATA as a laboratory for what the British called ‘air control’. Andrew Roe has provided a series of detailed discussions in the RAF’s invaluable Air Power Review, here and here and here, and brought much of his research together in Waging war in Waziristan (2010).

But for a rapid and sobering sense of how these campaigns were viewed from the air in the 1930s you need to watch this BBC interview with Group Captain Robert Lister, Wings over Waziristan, which includes extraordinary cine footage showing what he calls ‘tribal operations from the air’. Lister was posted to Peshawar in 1935, and soon after he arrived both the Army and the Air Force were ordered to put down ‘a tribal insurrection or rebellion’ in Waziristan. Their preferred method was to destroy villages by setting fire to individual houses, blowing them up, or bombing them from the air ‘to make them say “Right, it’s not worthwhile – come to terms.”‘ Listen as Lister says, in cut-glass tones, ‘It was a fair and just way of dealing with it: they started these troubles and had to be dealt with.’

And if you want to discover a different dimension to ‘unmanning’ aerial vehicles, listen from 08.00-08.40.

UPDATE: I’ve just discovered another film shot over Waziristan in 1937 by Leonard de Ville Chisman, which covers the air and ground war against the Faqir of Ipi described by Lister. It contains a number of strikingly similar shots, though there is of course no commentary: you can access it via Colonial Film: Moving Images of the British Empire here. On that remarkably informative site, Francis Gooding writes:

The official record of NWFP operations during 1936-7 – a thick volume, its size indicating the scale and seriousness of the conflict – contains full details about the manner in which aircraft were employed. The flag marches of November that sparked the revolt were accompanied by aircraft reconnaissance, and the record notes that ‘air reconnaissance requirements were met by one flight of No. 5 (Army Co-operation) Squadron’ (Govt of India, op.cit., 15), and the RAF also provided close cover for troops, and this pattern – reconnaissance with close support against the enemy – was repeated throughout the operations.

Reels 14 and 15 of the Chisman collection record precisely these kinds of encounters and air operations, with footage of bombing raids and the dropping of supplies to forward positions by parachute taken from within flying aircraft. Aircraft were also used to disseminate information and warnings about future punitive action (again, this was a tried and tested method, typical of colonial air policing; see Omissi, 1990, 154-5). On 27 August 1937, for instance, ‘notices were dropped over the Shawal area warning the inhabitants that until the Faqir submitted to Government, any tribe sheltering him would be liable for punishment’ (Govt. of India, op.cit., 179), and reel 15 contains a sequence showing a pilot unfurling a large leaflet, with text in Pashto and Urdu. The following sequences show air-drops of these leaflets over hill country. There are also scenes showing armoured cars and tanks on the move, and a sequence apparently shot during a battle, with a line of artillery opening fire on hill positions.

The Faqir’s uprising was arguably the most serious colonial insurgency of the inter-war imperial period, and the films are remarkable in that they record scenes of action from a poorly remembered but major guerrilla conflict. Beyond this historical importance they have another significance, for they offer scenes of something only very rarely captured on film, despite its regular occurrence throughout the Empire – the recourse to the punitive deployment of heavy weaponry against subject peoples in revolt.