Since I read it yesterday I’ve been mesmerized by Maymanah Farwat‘s fine short essay at Jadaliyya on Baghdad-born artist Dia al-Azzawi‘s (pictured left) Sabra and Shatila Massacre currently on view at Tate Modern in London.

Since I read it yesterday I’ve been mesmerized by Maymanah Farwat‘s fine short essay at Jadaliyya on Baghdad-born artist Dia al-Azzawi‘s (pictured left) Sabra and Shatila Massacre currently on view at Tate Modern in London.

The artwork itself is copyright, and the Tate online pages describe but don’t display it, but if you click on the link to Jadaliyya above you can see it; it’s also – vividly – here, and there’s also a detail here and more here. The vast four-panelled work is a response to the massacre of Palestinians in two refugee camps in Lebanon in 1982 by Phalangist militias under the eyes of the Israeli Defense Force commanded by Ariel Sharon.

Within a labyrinth of death and the mundane (the remnants of domestic structures), the artist is relentless in his indictment, what he refers to as “a manifesto of dismay and anger.” Areas of white, where the eye would normally rest in a monochromatic composition, ignite horror, become corpses. Instances of Cubism are employed not to convey the dynamic movement of form but as a system of measure through which to count out cyclical disaster.

The artist started work on the project the day after the killings:

‘I had at that time a roll of paper and, without any preparatory sketches, the idea for the work came to me. I tried to visualize my previous experience of walking through this camp, with its small rooms separated by a narrow road, in the early 1970s.’

But this vast composition is more than a memory work: Dia al-Azzawi was also inspired by Jean Genet‘s Quatre heures à Chatila (‘Four Hours in Shatila’) (available in the Journal of Palestine Studies 12 (3) (1983) 3-22). As Ahdaf Soueif tells the story:

‘[Genet] was, it seems, one of the first foreigners to enter the Palestinian refugee camp of Shatila after the Christian Lebanese Phalange, with the compliance of the Israeli command, tortured and murdered hundreds of its inhabitants. There, pushing open doors wedged shut by dead bodies, Genet memorised the features, the position, the clothing, the wounds of each corpse till three soldiers from the Lebanese army drove him at gun point to their officer: “‘Have you just been there?’ [the officer] pointed to Shatila. ‘Yes.’ – ‘And did you see?’ — ‘Yes.’ — ‘Are you going to write about it?’ — ‘Yes.'”

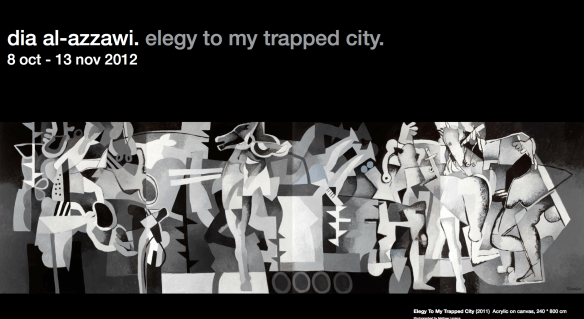

Sabra and Shatila Massacre retains that extraordinary, forensic attention to detail – to the wretched remnants of the ordinary – and it’s often compared to another, equally epic rendering of horror, Picasso‘s giant Guernica. (You can also see the parallels, I think, in the same artist’s Elegy to my trapped city (2011) below).

There’s more on the to-and-fro between the textual and the visual in relation to Sabra and Shatila in Zahra A. Hussein Ali, ‘Aesthetics of memorialization’, Criticism 51 (2010) 589-621. And Vimeo has an English-language version of Carlos Lapeña‘s film (2005) Four hours in Chatila inspired by Genet’s testimonial:

But if memory-work haunts these visualizations, then a film to watch in conjunction with and counterpoint to Lapeña’s is Ari Folman‘s ‘animated documentary’ Waltz with Bashir (2008) – described by Peter Bradshaw in the Guardian as ‘a military sortie into the past’ – in which the director tries to come to terms with his non-memory of being a young Israeli soldier in Lebanon in 1982 and, in so doing, converts Sabra and Shatila into lieux de mémoire.

Among the many thoughtful critical responses to the film, Natasha Mansfield‘s open-access essay on ‘Loss and mourning’ at Wide Screen 2 (1) (2010) deals with the differential distance between camera and animation (Ohad Landesman and Roy Bendor develop this in more detail in animation 6 (3) (2011) 353-70), Katrina Schlunke in ‘Animated documentary and the scene of death’ in South Atlantic Quarterly 110 (2011) 949-62 treats the final cut from animation to documented images of the massacre, while in ‘War Fantasies’, Modern Jewish Studies 9 (2010) 311-26 Raz Yosef – who also discusses these themes – objects to Folman’s focus on the Israeli ‘victim’ and its equation with the otherwise marginalised Palestinian victim.

The last is particularly troubling – see also Naira Antoun at electronic intifada and Ursula Lindsey at MERIP (‘Shooting film and crying’). For reflections on the thirtieth anniversary of the massacre, I recommend Seth Anziska in the New York Times (who documents US involvement), Zeina Azzam at Jadaliyya, and Habib Battah at al Jazeera. There’s also a moving briefing paper from Medical Aid for Palestinians here whose cover is based on Dia al-Azzawi’s artwork.

The last is particularly troubling – see also Naira Antoun at electronic intifada and Ursula Lindsey at MERIP (‘Shooting film and crying’). For reflections on the thirtieth anniversary of the massacre, I recommend Seth Anziska in the New York Times (who documents US involvement), Zeina Azzam at Jadaliyya, and Habib Battah at al Jazeera. There’s also a moving briefing paper from Medical Aid for Palestinians here whose cover is based on Dia al-Azzawi’s artwork.

And although it doesn’t address the visual – it’s an artful ‘misreading’ of Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish‘s memoir of Beirut via the Goldstone report on the Israeli assault on Gaza in 2009 – Barbara Harlow‘s ‘The geography and the event’, Interventions 14 (2012) 13-23 amplifies those contemporary resonances in ways that are worth attending to:

New ‘events’ – whether Operation Peace for Galilee (Beirut, 1982) or Operation Cast Lead (Gaza, 2009) – perhaps call, after all, for new ‘geographies’, such as universal jurisdiction, a principle in international law according to which states are allowed to claim criminal jurisdiction for actions – deemed heinous and to be crimes against humanity – committed outside their boundaries.