Sorry for the long silence – I’ve had my head down since soon after Christmas preparing the Tanner Lectures which I gave this past week in Cambridge [‘Reach from the sky: aerial violence and the everywhere war’]. The lectures were recorded and the video will be available on the Clare Hall website in a fortnight or so: more when I know more.

In outline – and after a rare panic attack the night before, which had me working until 2.30 in the morning – I organised the two Lectures like this:

ONE

Prelude: The historical geography of bombing

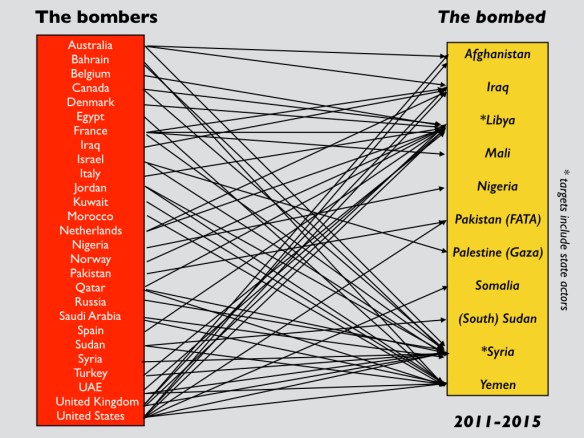

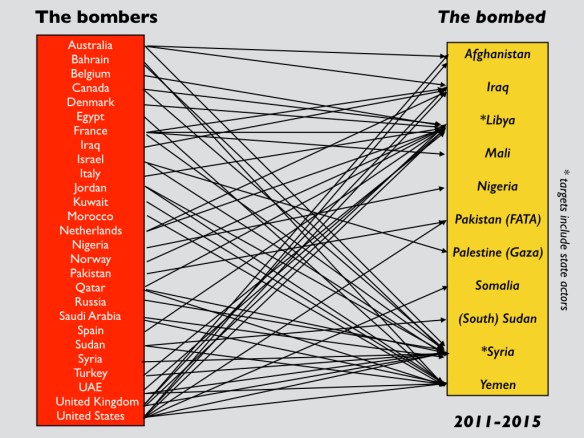

Bombing is back in the headlines but it never really left – and yet those who remain advocates of aerial violence don’t seem to have learned from its dismal history. They also ignore the geographies that have been intrinsic to its execution, both the division between ‘the bombers and the bombed’ (the diagram below is an imperfect and fragmentary example of what I have in mind) and the pulsating spaces through which bombing is performed.

Good bomb, bad bomb

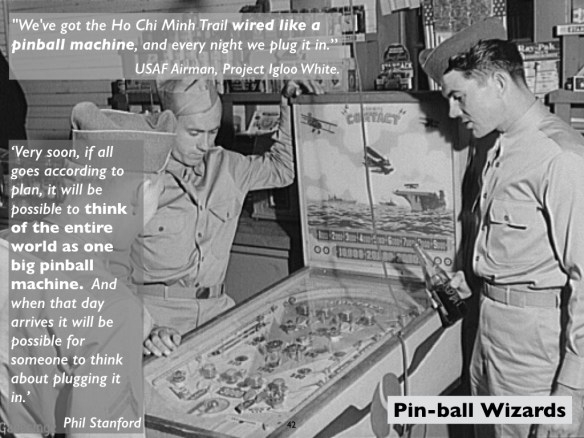

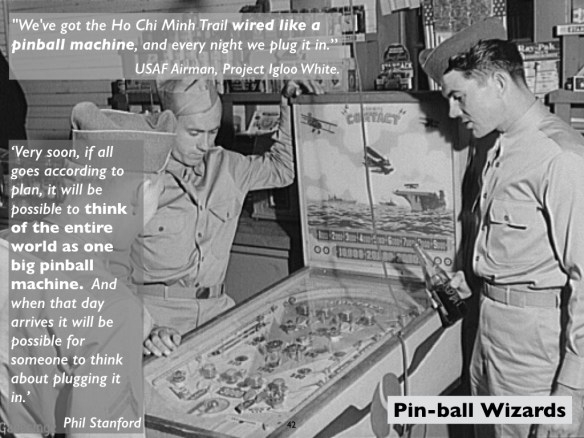

(with apologies to Mahmood Mamdani….) In the first part I traced The machinery of bombing from before the First World War through to today’s remote operations. Even though most early commentators believed that the primary role of military aircraft would be in reconnaissance, it was not long before they were being used to orchestrate artillery fire and to conduct bombing from the air. This sequence parallels the development of the Predator towards the end of the twentieth century. In fact, almost as soon as the dream of flight had been realised the possibility of ‘unmanned flight’ took to the air. Perhaps the most significant development, though, because it directs our attention to the wider matrix within which aerial violence takes place, was the development of the electronic battlefield in Laos and Cambodia. I’ve written about this in detail in ‘Lines of Descent‘ (DOWNLOADS tab); the electronic battlefield was important not because of what it did – the interdiction program on the Ho Chi Minh Trail was a spectacular failure (something which too many historians have failed to recognise) – but because of what it showed: it conjured up an imaginative landscape, an automated killing field, in which sensors and shooters were linked through computer systems and automatic relays. Contemporaries described the system as a vast ‘pinball machine’ (see the image below: you can have no idea how long it took me to track it down…).

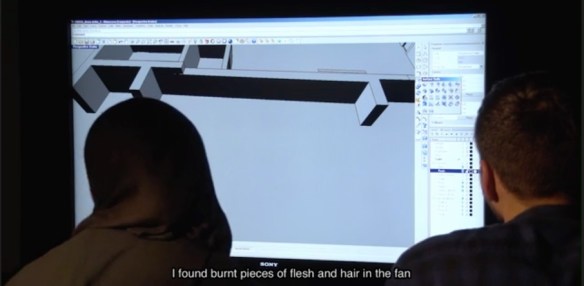

The analogy allowed me to segue into the parallel but wholly inadequate characterisation of today’s remote operations as reducing military violence to a video game.

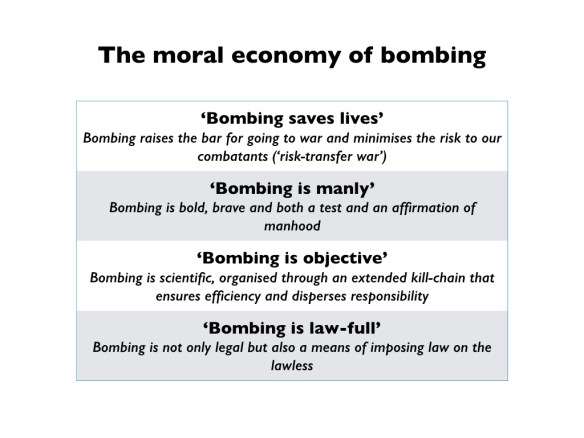

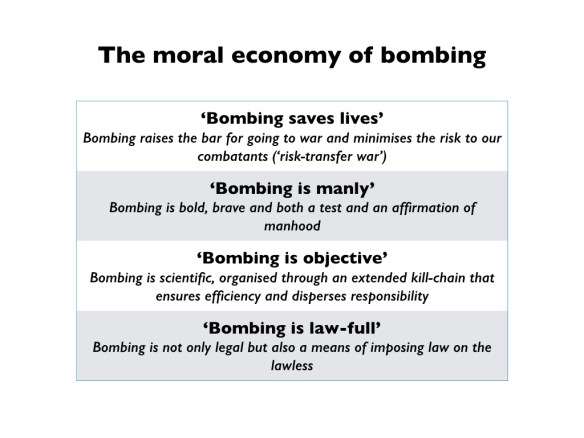

That is an avowedly ethical objection, of course, so I then turned to The moral economy of bombing. Here I dissected four of the main ways in which bombing has been justified. These have taken different forms at different times, and they intersect and on occasion even collide. But they have been remarkable persistent, so in each case I tracked the arguments involved and showed how they have been radicalised or compromised by the development of Predators and Reapers.

All of these justifications applied to ‘our bombs’, needless to say, which become ‘good bombs’, not to ‘their bombs’ – the ‘bad bombs’.

TWO

Killing Space

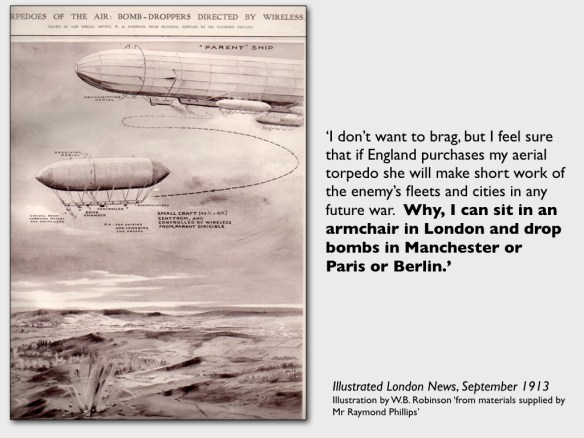

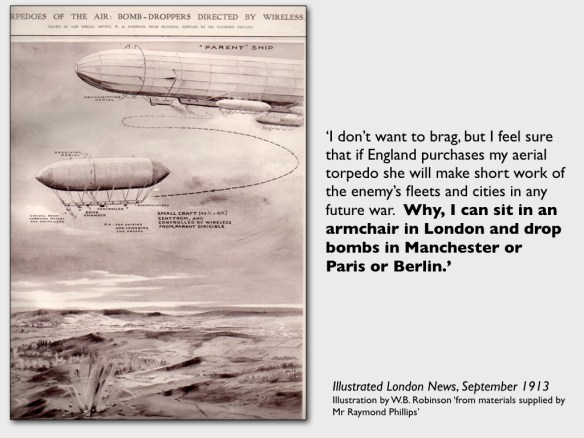

I started the second lecture by discussing The deconstruction of the battlefield; the wonder of Raymond Phillips’s fantasies of ‘aerial torpedoes‘ before the First World War was not so much their promise of ‘bomb-dropping by wireless’ but the targets:

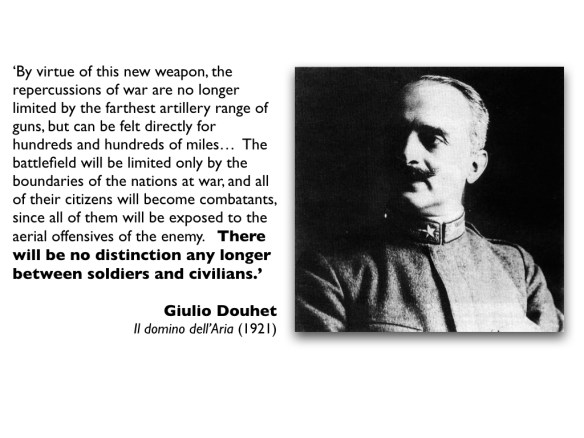

It was this radical extension of the battle space that counted. In the event, it was not British airships that dropped bombs on Berlin but German Zeppelins that bombed London and Paris, but the lesson was clear:

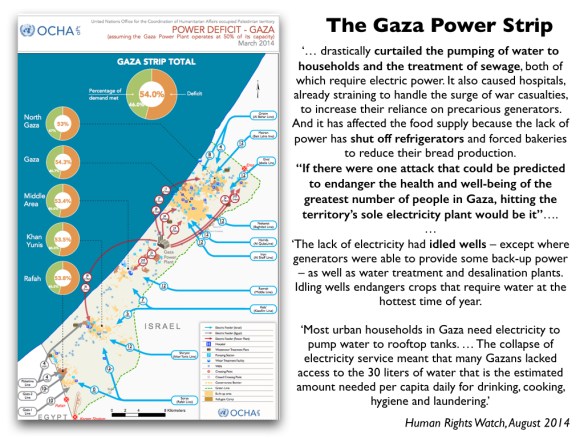

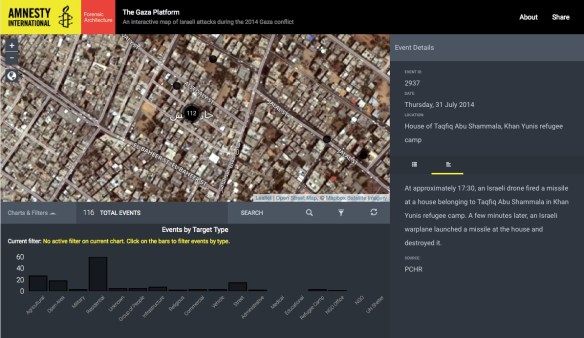

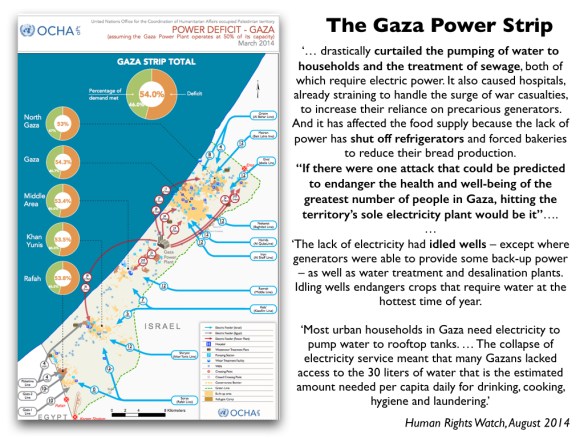

To explore the formations and deformations of the battlespace in more detail, I used the image of The dark heart of bombing to describe a battlespace that alternately expanded and contracted. So Allied bombing in the Second World war extended its deadly envelope beyond Germany, Italy and Japan into Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, France, the Netherlands, Norway and Romania; later the United States would bomb North Vietnam but reserved most of its ordnance for South Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia; and US air strikes in Afghanistan and Iraq would eventually spill over into Pakistan, Syria and elsewhere. In the course of those air wars, the accuracy of targeting improved until it was possible to aim (if not always to hit) point-targets – individual buildings and eventually individual people – but this contraction of the killing space was accompanied by its expansion. These ‘point-targets’ were selected because they were vital nodes that made possible the degradation or even destruction of an entire network. Hence, for example, the Israeli attack on the Gaza power station (more in a previous post here):

A similar argument can be made about the US Air Force’s boast that it can now put ‘warheads on foreheads’, and I linked the so-called individuation of warfare to the US determination to target individuals wherever they go – to what Jeremy Scahill and others describe as the production of a newly expanded ‘global battlefield’. What lies behind this is more than the drone, of course, since these killing fields rely on a global system of surveillance orchestrated by the NSA, and I sketched its contours and showed how they issued in the technical production of an ‘individual’ not as a fleshy, corporeal person but as a digital-statistical-spatial artefact (what Ian Hacking once called ‘making people up’ and what Grégoire Chamayou calls ‘schematic bodies‘).

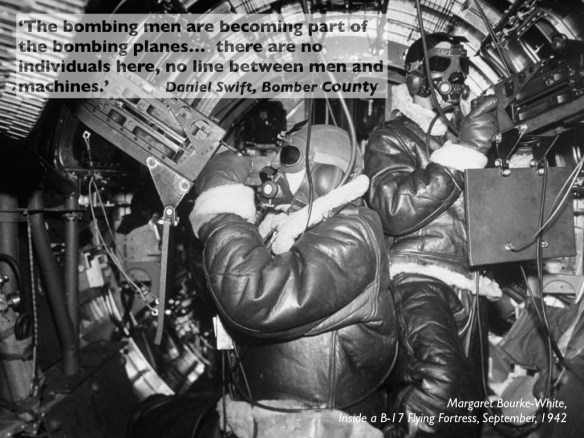

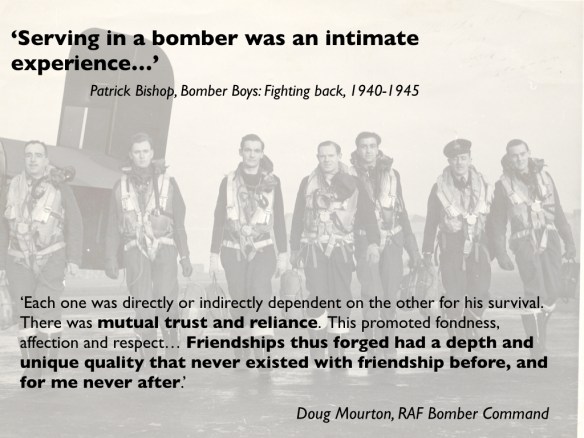

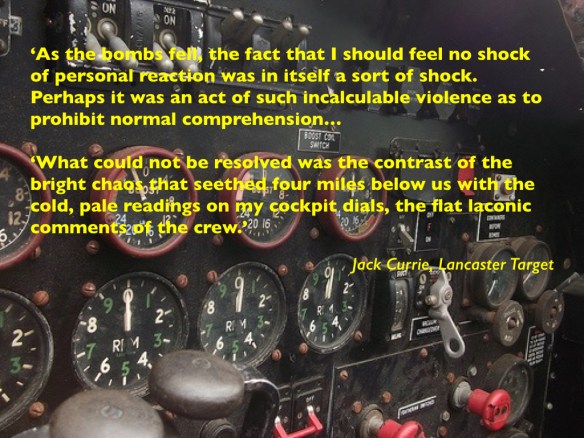

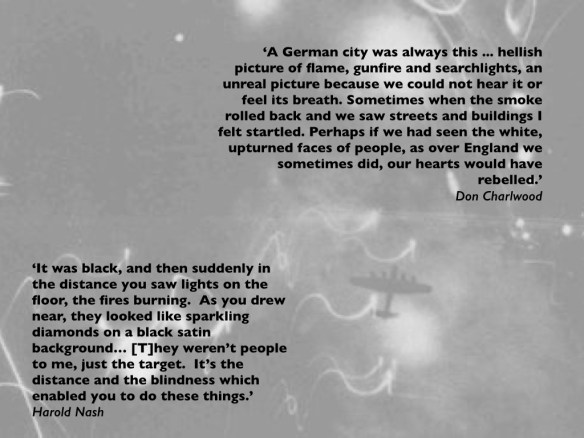

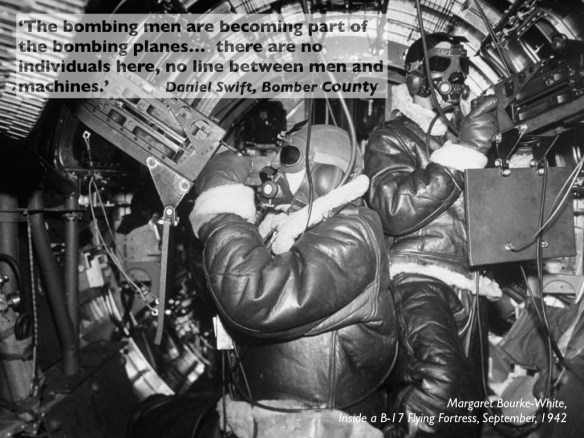

Next I explored a different dialectical geography of the battlespace: Remote splits: intimacy and detachment. I started with RAF Bomber Command and traced in detail the contrast between the intimacy between members of bomber crews (a mutual dependence reinforced by the bio-convergence between their bodies and the machinery of the bomber itself) and the distance and detachment through which they viewed their targets.

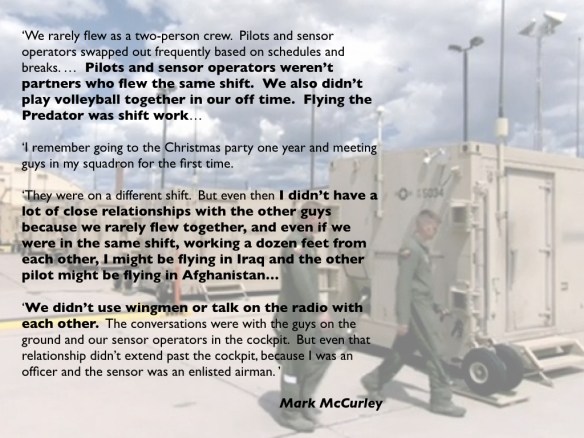

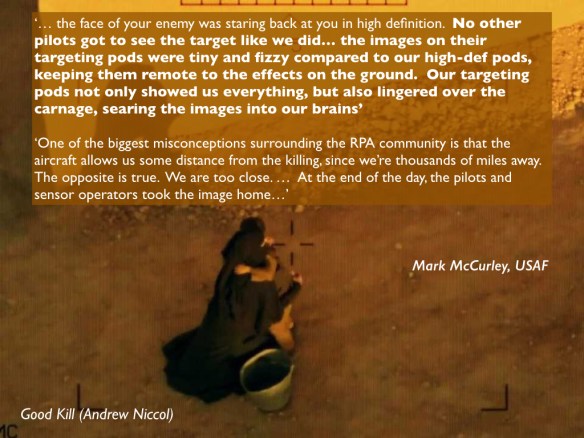

There’s much more on this in ‘Doors into nowhere‘ (DOWNLOADS tab), though I think my discussion in the Lectures breaks new ground. All of this is in stark contrast to today’s remote operations, where – as Lucy Suchman reminds us – there remains a remarkable (though different) degree of bioconvergence and yet now a persistent isolation and anomie is felt by many pilots and sensor operators who work in shifts:

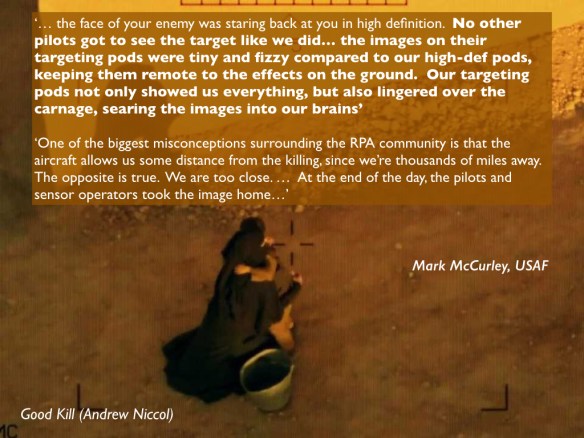

This is thrown into relief by the closeness remote operators feel to the killing space itself, an immersion made possible through the near real-time full-motion video feeds, the internet relay chatter and the radio communications with troops on the ground (where there are any). In contrast to the bomber crews of the Second World War – or those flying over the rainforests of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia – there is a repeated insistence on a virtualized proximity to the target.

But I used a discussion of Andrew Niccol‘s Good Kill to raise a series of doubts about what drone crews really can see, as a way into the next section, Sweet target, which provided an abbreviated presentation of the US air strike in Uruzgan I discuss in much more (I hope forensic) detail in Angry Eyes (see here and here). That also allowed me to bring together many of the key themes I had isolated in the course of the two lectures.

As I approached my conclusion, I invoked Thomas Hippler‘s Le gouvernement du ciel: Histoire globale des bombardements aériens, (I’ve just discovered that Verso will publish the English-language version later this year or early next: Governing from the skies: a global history of aerial bombing):

I’m not convinced that the military and paramilitary violence being visited on people today is all ‘low-intensity’ (Gaza? Afghanistan? Iraq? Syria? Yemen?). But neither do I think it’s ‘de-territorialised’, unless the word is flattened into a conventionally Euclidean frame. Hence, following Stuart Elden‘s lead, I treated territory as a political-juridical technology whose calibrations and enclosures assert, enable and enforce a claim over bodies-in-spaces. And it was those ‘bodies-on-spaces’ that brought me, finally, to The loneliest space of all: the irreducible, truly dreadful loneliness of death and grief:

Behind the body-counts and the odious euphemisms of collateral damage and the rest lies the raw, inconsolable loss so exquisitely, painfully rendered in ‘Sky of Horoshima‘…

In the coming days I’ll post some of the key sections of the Lectures in more detail, which I’ll eventually develop into long-form essays.

I learned a lot from the expert and wonderfully constructive commentaries after the Lectures from Grégoire Chamayou, Jochen von Bernstorff and Chris Woods, and I’ll do my best to incorporate their suggestions into the final version.

In his response Grégoire traced my project on military violence in general and bombing/drones in particular back to a series of arguments I’d developed in Geographical imaginations in 1994 about vision, violence and corporeality; I had overlooked these completely, full of the conceit that my work had never stood still…. I shall go back, re-read and think about that some more, since some of the ideas that Grégoire recovered (and elaborated) may be even more helpful to me now. Jochen and Chris also gave me much food for thought, so I shall be busy in the coming months, and I’m immensely grateful to all three of them.