Following up my comments on the Pentagon’s new Law of War Manual, issued last month: commentaries are starting to appear (it’s not surprising these are taking so long: the new version runs to 1200 pages).

Following up my comments on the Pentagon’s new Law of War Manual, issued last month: commentaries are starting to appear (it’s not surprising these are taking so long: the new version runs to 1200 pages).

Just Security is hosting a forum on the Manual, organised by Eric Jensen and Sean Watts. They are both deeply embedded in the debate: Eric is a Professor at Brigham Young Law School and was formerly Chief of the Army’s International Law Branch and Legal Advisor to US military forces in Iraq and Bosnia, while Sean is a Professor at Creighton University Law School and on the Department of Law faculty at the United States Military Academy at West Point; he is also Senior Fellow at the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence and served in the US Army’s Judge Advocate General’s Corps.

In the opening salvo, Sean focuses on the Manual‘s identification of three core principles:

“Three interdependent principles – military necessity, humanity, and honor – provide the foundation for other law of war principles, such as proportionality and distinction, and most of the treaty and customary rules of the law of war.”

The implications of this formulation are more far reaching than you might think. Necessity, proportionality and distinction have long been watchwords, but the inclusion – more accurately, Sean suggests, the resurrection – of ‘humanity’ and ‘honor’ is more arresting: in his view, the first extends the protection from ‘unnecessary suffering’ while the second ‘marks an important, if abstract revival of good faith as a legal restraint on military operations’.

Watch that space for more commentaries, inside and outside the armed camp.

Others have already taken a much more critical view of the Manual.

Claire Bernish draws attention to two particularly disturbing elements here. First, like several other commentators, she notes passages that allow journalists to be construed as legitimate targets. While the Manual explains that ‘journalists are civilians’ it also insists there are cases in which journalists may be ‘members of the armed forces […] or unprivileged belligerents.’ Apparently, Claire argues,

‘reporters have joined the ranks of al-Qaeda in this new “unprivileged belligerent” designation, which replaces the Bush-era term, “unlawful combatants.” What future repercussions this categorization could bring are left to the imagination, even though the cited reasoning—the possibility terrorists might impersonate journalists—seems legitimate. This confounding label led a civilian lawyer to say it was “an odd and provocative thing for them to write.”‘

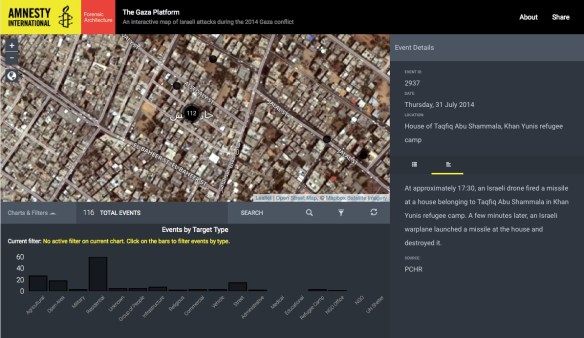

Other commentators, mindful of incidents in which the US military has been accused of targeting independent (non-embedded) journalists, have read this as far more than provocation. Like other claims registered in the Manual, this has implications for other armed forces – and in this particular case, for example, Ken Hanly points out that ‘what is allowed for NATO and the US is surely legitimate for Israel.’

This is not as straightforward as he implies, though. Eric Jensen agrees that

‘[T]he writers had to be aware this manual would also be looked to far beyond the US military, including by other nations who are formulating their own law of war (LOW) policies, allies who are considering US policy for purposes of interoperability during combined military operations, transnational and international organizations such as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) who look to such manuals when considering the development of customary practice, and even national and international tribunals who adjudicate LOW questions with respect to the criminality of individual actions.

While Eric acknowledges ‘the inevitable use of [the Manual] in the determination of customary practice.’ however, he also argues that the authors of the Manual go out of their way to preclude this possibility: they ‘wanted to be very clear that they did not anticipate they were writing into law the US position on the law of war.’

Second, Claire draws attention to a list of weapons with specific rules on use’ (Section 6.5.1), which includes cluster munitions, herbicides and explosive ordnance, and a following list of other ‘lawful weapons’ (Section 6.5.2) for which ‘there are no law of war rules specifically prohibiting or restricting the following types of weapons by the U.S. armed forces’; the list includes drones and Depleted Uranium munitions. These designations are all perfectly accurate, but Claire’s commentary fastens on the fact that at least two of these weapons have been outlawed by many states. She draws attention to the hideous consequences of DU and cluster bombs, and explains that cluster bombs:

‘are delineated in the manual as having “Specific Rules on Use”— notably, such weapons’ use “may reflect U.S. obligations under international law” [emphasis added]. While this is technically apt, cluster bombs have been banned by the 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions—which was agreed to by 116 countries around the world. The U.S. stands out in joining infamous human rights violator, Saudi Arabia, in its refusal to sign. These insidious munitions leave unexploded ordnance for months, or even decades, after the originating bomb was dropped. Children are often maimed or killed when they unwittingly mistake them for toys.’

Meanwhile, also at Just Security but seemingly not part of the Forum, Adil Ahmad Haque has attacked the Manual‘s discussion of ‘human shields’:

The Defense Department apparently thinks that it may lawfully kill an unlimited number of civilians forced to serve as involuntary human shields in order to achieve even a trivial military advantage. According to the DOD’s recently released Law of War Manual, harm to human shields, no matter how extensive, cannot render an attack unlawfully disproportionate. The Manual draws no distinction between civilians who voluntarily choose to serve as human shields and civilians who are involuntarily forced to serve as human shields. The Manual draws no distinction between civilians who actively shield combatants carrying out an attack and civilians who passively shield military objectives from attack. Finally, the Manual draws no distinction between civilians whose presence creates potential physical obstacles to military operations and civilians whose presence creates potential legal obstacles to military operations. According to the Manual, all of these count for nothing in determining proportionality under international law.

If true, this would dramatically qualify the discussion of ‘humanity’ and ‘honor’ above; but, not surprisingly, Charles Dunlap will have none of it. He objects not only to Adil’s reading of the Manual, but also the logic that lies behind his criticism:

Killing those who do the vast majority of the killing of civilians can save lives. It really can be that simple.

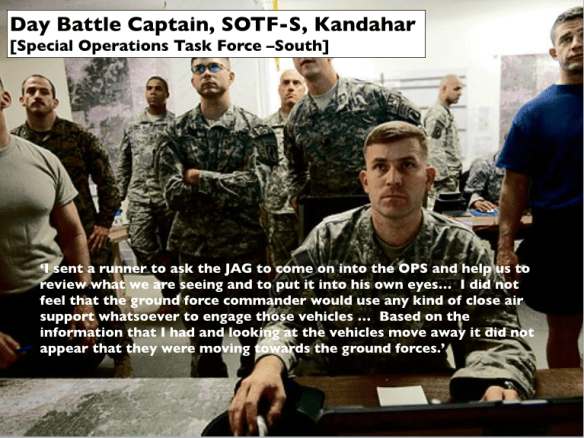

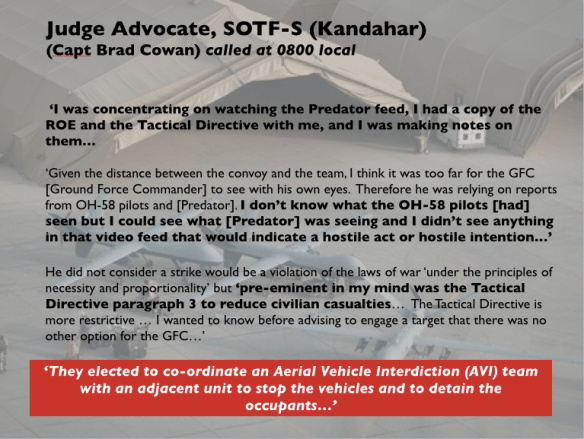

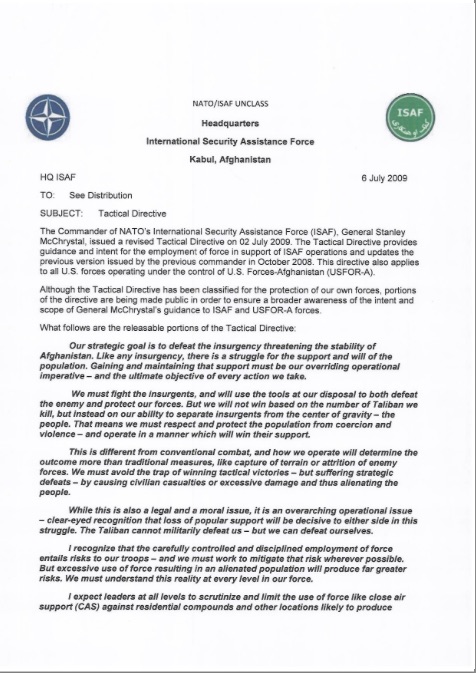

Experience shows that well-meaning efforts to curb the use of force can have disastrous effects on civilians. Think about the restrictions on airstrikes imposed by Gen. Stanley McChrystal in Afghanistan in mid-2009. The result? By the time he was fired a year later in June 2010, civilian casualties had jumped a heart-rending 31% entirely because of increased killings by anti-government forces. (In addition, casualties among friendly troops hit an all-time high in 2010.)

[The unclassified section of McChrystal’s Tactical Directive (above) is here]

When Gen. David Petraeus took command in mid-2010, he took a different, more aggressive approach. While still scrupulously adhering to the law of war, he clarified the rules of engagement in a way that produced a tripling of the number of airstrikes. The result? The increase in civilian casualties was cut in half to 15% by the end of 2010. Under Petraeus’ more permissive interpretation of the use of force against the Taliban and other anti-government forces, the increase the following year was cut almost in half again to 8% (and losses of friendly troops fell 20%). To reiterate, although counterintuitive to some critics, restricting force by law or policy can actually jeopardize the lives of the civilians everyone wants to protect.

Michael O’Hanlon at the Brookings Institue makes exactly the same argument about the Manual here (scroll down), but Dunlap’s sense is much sharper: the Manual, he says, ‘is designed to win wars in a lawful way that fully internalizes, as it says itself on several occasions, the “realties of war.”’ This is immensely important because in effect it acknowledges that neither the Manual nor the laws of war are above the fray. If the Manual ‘is designed to win wars in a lawful way’ that is precisely because law is in the army’s baggage train, fully incorporated into the juridification of later modern war. Law is at once a powerful weapon and a moving target.

The dilemmas precipitated by the unintentional killing of civilians in war, or ‘collateral damage’, shape many aspects of military conduct, yet noticeable by its absence has been a methodical examination of the place and role of this phenomenon in modern warfare. This book offers a fresh perspective on a distressing consequence of conflict.