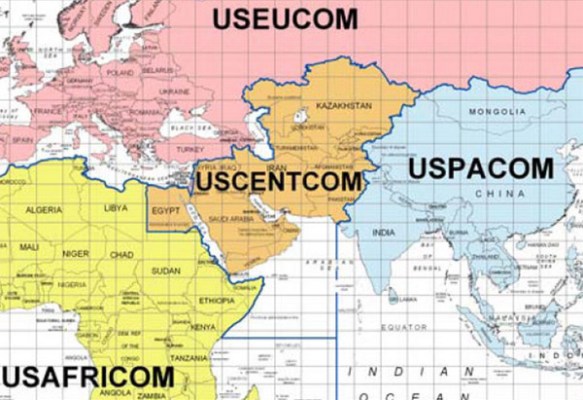

Islamic State has claimed responsibility for last night’s co-ordinated terrorist attacks in Paris, calling them the ‘first of the storm’ and castigating the French capital as ‘the capital of prostitution and obscenity’. Walter Benjamin‘s celebrated ‘capital of the nineteenth century’ has been called many things, of course, and as I contemplated the symbol that has now gone viral (above), designed by Jean Jullien, I realised that Paris had been the stage for the 1919 Peace Conference that not only established the geopolitical settlement after the First World War but also accelerated the production of today’s ‘Middle East’ by awarding ‘mandates’ to both Britain and France and crystallising the secret Sykes-Picot agreement struck between the two powers in 1916 (more on that from the Smithsonian here).

Margaret MacMillan has a spirited summary of the conference here, with some lively side-swipes at the astonishing lack of geographical knowledge displayed by the principal protagonists. Much on my mind was the French mandate for Syria and Lebanon:

For as I watched Friday night’s terrifying events in Paris unfold, I had also been reminded of the horrors visited upon Beirut the evening before.

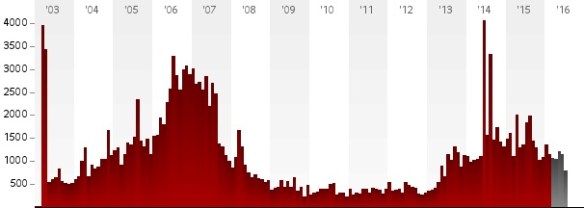

Two suicide bombers detonated their explosives in Burj el-Barajneh in the city’s southern suburbs; the attacks were carefully timed for the early evening, when the streets were full of families gathering after work and crowds were leaving mosques after prayers: they killed 43 people and injured more than 200 others.

Islamic State issued a statement saying that ’40 rafideen– a pejorative term for Shiite Muslims used by Sunni Islamists – were killed in the “security operation”’ and claimed the attacks were in retaliation for Hezbollah’s role in the Syrian war.

In the 1950s and 60s Beirut was known as ‘the Paris of the Middle East’ (above) – widely seen as more chic, more cosmopolitan than the ‘Paris-on-the-Nile’ created by Francophile architects and planners west of the old city of Cairo in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Now I’ve always been troubled by these city switchings – the ‘Venice of the North’ is another example – because they marginalise what is so distinctive about the cities in question and crush the creativity that is surely at the very heart of their urbanity.

And yet, after last night, I can see a different point in the politics of comparison (from Kennedy’s Ich bin ein Berliner to the post 9/11 insistence that “we are all New Yorkers…”). More accurately, in the politics of non-comparison: as Chris Graham asks (and answers): why the silence over what happened in Beirut on Thursday? Why no mobilisation of the news media and no interruptions to regular programmes on TV or radio? Why no anguished personal statements from Obama, Cameron or, yes, Hollande?

Nobody has put those questions with more passion and justice than Elie Fares writing from Beirut:

I woke up this morning to two broken cities. My friends in Paris who only yesterday were asking what was happening in Beirut were now on the opposite side of the line. Both our capitals were broken and scarred, old news to us perhaps but foreign territory to them….

Amid the chaos and tragedy of it all, one nagging thought wouldn’t leave my head. It’s the same thought that echoes inside my skull at every single one of these events, which are becoming sadly very recurrent: we don’t really matter.

When my people were blown to pieces on the streets of Beirut on November 12th, the headlines read: explosion in Hezbollah stronghold, as if delineating the political background of a heavily urban area somehow placed the terrorism in context.

When my people died on the streets of Beirut on November 12th, world leaders did not rise in condemnation. There were no statements expressing sympathy with the Lebanese people. There was no global outrage that innocent people whose only fault was being somewhere at the wrong place and time should never have to go that way or that their families should never be broken that way or that someone’s sect or political background should never be a hyphen before feeling horrified at how their corpses burned on cement. Obama did not issue a statement about how their death was a crime against humanity; after all what is humanity but a subjective term delineating the worth of the human being meant by it?

Here we might pause to remind ourselves that most of the victims of Islamic State have been Muslims (see, for example, here and here).

Here Hamid Dabashi‘s reflections are no less acute:

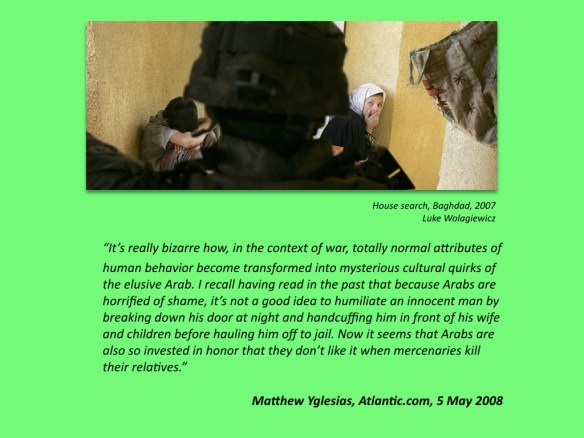

In a speech expressing his solidarity and sympathy with the French, US President Barack Obama said, “This is an attack not just on Paris, it’s an attack not just on the people of France, but this is an attack on all of humanity and the universal values that we share.”

Of course, the attack on the French is an attack on humanity, but is an attack on a Lebanese, an Afghan, a Yazidi, a Kurd, an Iraqi, a Somali, or a Palestinian any less an attack “on all of humanity and the universal values that we share”? What is it exactly that a North American and a French share that the rest of humanity is denied sharing?

In his speech, UK Prime Minister David Cameron, speaking as a European, was emphatic about “our way of life”, and then addressing the French he added: “Your values are our values, your pain is our pain, your fight is our fight, and together, we will defeat these terrorists.”

What exactly are these French and British values? Can, may, a Muslim share them too – while a Muslim? Or must she or he first denounce being a Muslim and become French or British before sharing those values?

These are loaded terms, civilisational terms, and culturally coded registers. Both Obama and Cameron opt to choose terms that decidedly and deliberately turn me and millions of Muslims like me to their civilisational other.

They make it impossible for me to remain the Muslim that I am and join them and millions of other people in the US and the UK and the EU in sympathy and solidarity with the suffering of the French.

As a Muslim I defy their provincialism, and I declare my sympathy and solidarity with the French; and I do so, decidedly, pointedly, defiantly, as a Muslim.

When Arabs or Muslims die in the hands of the selfsame criminal Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) gangs in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, or Lebanon, they are reduced to their lowest common denominator and presumed sectarian denominations, overcoming and camouflaging our humanity. But when French or British or US citizens are murdered, they are raised to their highest common abstractions and become the universal icons of humanity at large.

Why? Are we Muslims not human? Does the murder of one of us not constitute harm to the entire body of humanity?

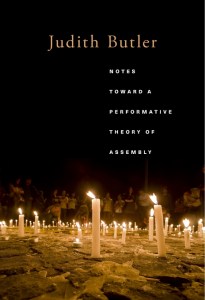

Elie’s and Hamid’s questions are multiple anguished variations of Judith Butler‘s trenchant demand: why are these lives deemed grievable and not those others?

Elie’s and Hamid’s questions are multiple anguished variations of Judith Butler‘s trenchant demand: why are these lives deemed grievable and not those others?

To ask this is not to minimise the sheer bloody horror of mass terrorism in Paris nor to marginalise the terror, pain and suffering inflicted last night on hundreds of innocents – and also affecting directly or indirectly thousands and thousands of others.

In fact the question assumes a new urgency in the wake of what happened in Paris – where I think the most telling comparison is with Beirut and not with the attacks on Charlie Hebdo (see my commentary here) – because the extreme right (the very same people who once elected to stuff “Freedom Fries” down their throats) has lost no time in using last night’s events to ramp up their denigration of Syrian refugees and their demands for yet more bombing (and dismally failing to see any connection between the two). You can see something of what I mean here.

And so I suggest we reflect on Jason Burke‘s commentary on Islamic State’s decision to ‘go global’ and its tripartite strategy of what he calls ‘terrorise, mobilise, polarise’. The three are closely connected, but it’s the last term that is crucial:

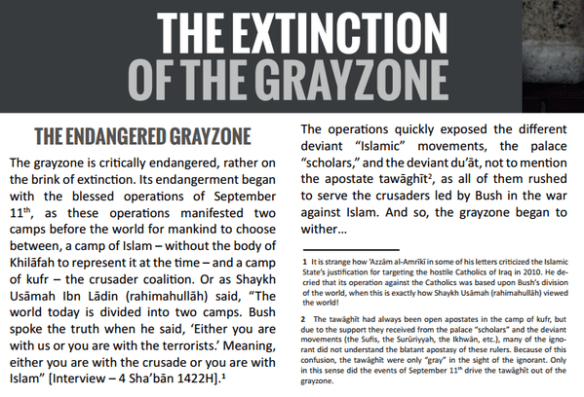

In February this year, in a chilling editorial in its propaganda magazine, Dabiq, Isis laid out its own strategy to eliminate what the writer, or writers, called “the grey zone”.

This was, Isis said, what lay between belief and unbelief, good and evil, the righteous and the damned. It was home, too, to all those who had yet to commit to the forces of either side.

The grey zone, Isis claimed, had been “critically endangered [since] the blessed operations of September 11th”, as “these operations showed the world” the two camps that mankind must choose between.

Over the years, since successive violent acts had narrowed the grey zone to the point where by the end of 2014 “the time had come for another event to … bring division to the world and destroy the grey zone everywhere”.

More from Ben Norton here. The imaginative geographies of Islamic State overlap with those spewed by the extreme right in Europe and North America and, like all imaginative geographies, they have palpable effects: not fifty shades of grey but fifty versions of supposedly redemptive violence.

UPDATE (1): For more on these questions – and the relevance of Butler’s work– see Carolina Yoko Furusho‘s essay ‘On Selective Grief’ at ‘Critical Legal Thinking here.

As it happens, Judith is in Paris, and posted a short reflection on Verso’s blog here. She ends with these paragraphs:

My wager is that the discourse on liberty will be important to track in the coming days and weeks, and that it will have implications for the security state and the narrowing versions of democracy before us. One version of liberty is attacked by the enemy, another version is restricted by the state. The state defends the version of liberty attacked as the very heart of France, and yet suspends freedom of assembly (“the right to demonstrate”) in the midst of its mourning and prepares for an even more thorough militarization of the police. The political question seems to be, what version of the right-wing will prevail in the coming elections? And what now becomes a permissable right-wing once le Pen becomes the “center”. Horrific, sad, and foreboding times, but hopefully we can still think and speak and act in the midst of it.

Mourning seems fully restricted within the national frame. The nearly 50 dead in Beirut from the day before are barely mentioned, and neither are the 111 in Palestine killed in the last weeks alone, or the scores in Ankara. Most people I know describe themseves as “at an impasse”, not able to think the situation through. One way to think about it may be to come up with a concept of transversal grief, to consider how the metrics of grievability work, why the cafe as target pulls at my heart in ways that other targets cannot. It seems that fear and rage may well turn into a fierce embrace of a police state. I suppose this is why I prefer those who find themselves at an impasse. That means that this will take some time to think through. It is difficult to think when one is appalled. It requires time, and those who are willing to take it with you – something that has a chance of happening in an unauthorized “rassemblement” [gathering].

UPDATE (2): At Open Democracy Nafeez Mossadeq Ahmed has a helpful essay, ‘ISIS wants to destroy the “grey zone”: Here’s how we defend it’: access here.