And so what Tom Junod calls the lethal presidency continues… though it surely would have done whoever occupied the White House for the next four years.

And so what Tom Junod calls the lethal presidency continues… though it surely would have done whoever occupied the White House for the next four years.

Much of the discussion of US targeted killing has centred on both its status under international law and on the quasi-judicial armature through which various government agencies, including the Pentagon and the Central Intelligence Agency, draw up and adjudicate their kill lists of named individuals who are liable to a ‘personality strike’. But the majority of US targeted killings turn out to be ‘signature strikes’.

Signature strikes were initiated under President George W. Bush, who authorised more permissive rules of engagement in January/February 2008. According to Eric Schmitt and David Sanger, writing in the New York Times,

[A] series of meetings among President Bush’s national security advisers resulted in a significant relaxation of the rules under which American forces could aim attacks at suspected Qaeda and Taliban fighters in the tribal areas near Pakistan’s border with Afghanistan.

The change, described by senior American and Pakistani officials who would not speak for attribution because of the classified nature of the program, allows American military commanders greater leeway to choose from what one official who took part in the debate called “a Chinese menu” of strike options.

Instead of having to confirm the identity of a suspected militant leader before attacking, this shift allowed American operators to strike convoys of vehicles that bear the characteristics of Qaeda or Taliban leaders on the run, for instance, so long as the risk of civilian casualties is judged to be low.

Under Obama signature strikes increased in frequency, and Micah Zenko notes that the President’s initial reluctance soon yielded to endorsement:

According to Daniel Klaidman, when Obama was first made aware of signature strikes, the CIA’s deputy director clarified: “Mr. President, we can see that there are a lot of military-age males down there, men associated with terrorist activity, but we don’t necessarily know who they are.” Obama reacted sharply, “That’s not good enough for me.” According to one adviser describing the president’s unease: “‘He would squirm … he didn’t like the idea of kill ‘em and sort it out later.’” Like other controversial counterterrorism policies inherited by Obama, it did end up “good enough,” since he allowed the practice to stand in Pakistan, and in April authorized the CIA and JSOC to conduct signature strikes in Yemen as well.

Today signature strikes are frequently triggered not on the fly – a sudden response to an imminent threat – but by a sustained ‘pattern of life’ that arouses the suspicion of distant observers and operators. This depends on persistent surveillance – on full motion video feeds and a suite of algorithms that decompose individual traces and networks – some of which involve a weaponized version of Hägerstrand’s time-geography: see, for example, GeoTime 5 here.

We know even less about the legal authority for these attacks, but Kevin Jon Heller has a new essay on their legality up at the wonderful open access resource that is SSRN [Social Science Research Network] here, and there are preliminary responses at Opinio Juris here. This is the abstract:

The vast majority of drone attacks conducted by the U.S. have been signature strikes – strikes that target “groups of men who bear certain signatures, or defining characteristics associated with terrorist activity, but whose identities aren’t known.” In 2010, for example, Reuters reported that of the 500 “militants” killed by drones between 2008 and 2010, only 8% were the kind “top-tier militant targets” or “mid-to-high-level organizers” whose identities could have been known prior to being killed. Similarly, in 2011, a U.S. official revealed that the U.S. had killed “twice as many ‘wanted terrorists’ in signature strikes than in personality strikes.”

Despite the U.S.’s intense reliance on signature strikes, scholars have paid almost no attention to their legality under international law. This article attempts to fill that lacuna. Section I explains why a signature strike must be justified under either international humanitarian law (IHL) or international human rights law (IHRL) even if the strike was a legitimate act of self-defence under Article 51 of the UN Charter. Section II explores the legality of signature strikes under IHL. It concludes that although some signature strikes clearly comply with the principle of distinction, others either violate that principle as a matter of law or require evidence concerning the target that the U.S. is unlikely to have prior to the attack. Section III then provides a similar analysis for IHRL, concluding that most of the signature strikes permitted by IHL – though certainly not all – would violate IHRL’s insistence that individuals cannot be arbitrarily deprived of their right to life.

The most interesting section (for me) is Kevin’s discussion of ‘evidentiary adequacy’. Most of the examples he discusses appear to be derived from CIA-directed strikes in Pakistan – drawing on the Stanford/NYU report on Living under drones – and, for that very reason, are remarkably limited. But we know much more about problems of evidence – and inference – from strikes conducted by the US military in Afghanistan…

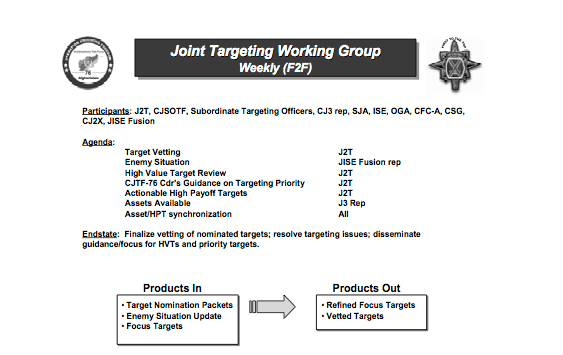

The first point to make, then, is that targeted killings are also carried out by the US military – indeed, the US Air Force has advertised its ability to put ‘warheads on foreheads‘ – and a strategic research report written by Colonel James Garrett for the US Army provides a rare insight into the process followed by the military in operationalising its Joint Prioritized Effects List (JPEL). Wikileaks has provided further information about JSOC’s Task Force 373 – see, for example, here and here – but the focus of Garrett’s 2008 report is the application of the legal principles of necessity and proportionality (two vital principles in the calculus of International Humanitarian Law (IHL) discussed by Kevin) in counterinsurgency operations. Garrett describes ‘time-sensitive targeting procedures’ used by the Joint Targeting Working Group to order air strikes on ‘high-value’ Taliban and al-Qaeda leaders in Afghanistan, summarised in this diagram:

Notice that the members included representatives from both Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force (CJSOTF) and the CIA (‘Other Government Agency’, OGA). This matters because Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) – once commanded by General Stanley McChrystal – and the CIA, even though they have their own ‘kill lists’, often co-operate in targeted killings and are both involved in strikes outside Afghanistan. Indeed, there have been persistent reports that many of the drone strikes in Pakistan attributed to the CIA – even if directed by the agency – have been carried out by JSOC. Here is Jeremy Scahill citing a ‘military intelligence source’:

“Some of these strikes are attributed to OGA [Other Government Agency, intelligence parlance for the CIA], but in reality it’s JSOC and their parallel program of UAVs [unmanned aerial vehicles] because they also have access to UAVs. So when you see some of these hits, especially the ones with high civilian casualties, those are almost always JSOC strikes.”

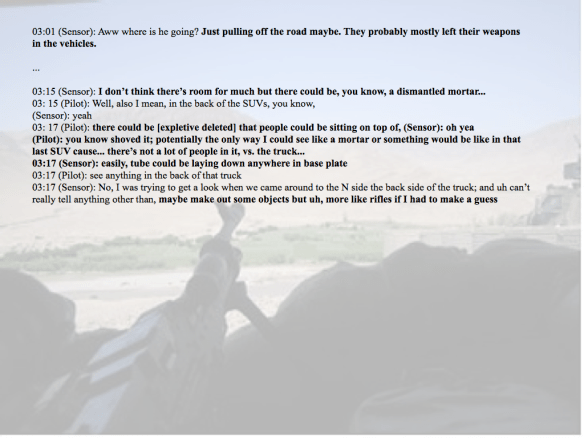

Garrett’s discussion clearly refers to ‘personality strikes’, but – second – the distinction between the evidential/inferential apparatus used for a ‘personality strike’ and for a ‘signature strike’ is by no means clear-cut. Kate Clark‘s report for the Afghan Analysts Network describes the attempted killing of Muhammad Amin, the Taliban deputy shadow governor of Takhar province. On 2 September 2010 ISAF announced that a ‘precision air strike’ earlier that morning had killed him and ‘nine other militants’. The target had been under persistent surveillance from remote platforms – what Petraeus later called ‘days and days of the unblinking eye’ – until two strike aircraft repeatedly bombed the convoy in which he was travelling. Two attack helicopters were then ‘authorized to re-engage’ the survivors. The victim was not the designated target, however, but Zabet Amanullah, the election agent for a parliamentary candidate; nine other campaign workers died with him. Clark’s painstaking analysis clearly shows that one man had been mistaken for the other, which she attributed to an over-reliance on ‘technical data’ – on remote signatures. Special Forces had concentrated on tracking cell phone usage and constructing social networks. ‘We were not tracking the names,’ she was told, ‘we were targeting the telephones.’

This is unlikely to be an isolated incident. Here for example is Gareth Porter:

‘…the link analysis methodology employed by intelligence analysis is incapable of qualitative distinctions among relationships depicted on their maps of links among “nodes.” It operates exclusively on quantitative data – in this case, the number of phone calls to or visits made to an existing JPEL target or to other numbers in touch with that target. The inevitable result is that more numbers of phones held by civilian noncombatants show up on the charts of insurgent networks. If the phone records show multiple links to numbers already on the “kill/capture” list, the individual is likely to be added to the list.’

In the Takhar case, despite informed protests to the contrary, ISAF insisted that they had killed their intended target (added emphases are mine):

PBS/Frontline screened a Stephen Grey/Dan Edge documentary on the Takhar incident last year, Kill/Capture, from which the images below are taken (reworked for my presentation on Lines of descent) and which, like Kate Clark’s remarkable report on which it drew, gave the lie to the ISAF statement; the film included an Afghan Police video of the aftermath of the attack: more here, video here, and transcript here.

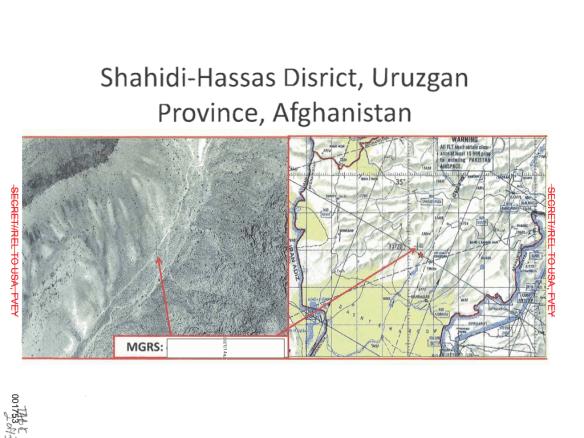

Finally, there is a persistent propensity to read hostile intent into innocent actions. In ‘From a view to a kill’ (DOWNLOADS tab) I describe in detail an attack launched on 21 October 2010 near Shahidi Hassas in Uruzgan province in central Afghanistan. In the early morning a Predator was tasked to track three vehicles travelling down a mountain road, several miles away from a Special Forces unit moving in to search a village for an IED factory.

The Predator crew in Nevada had radio contact with the Special Forces Joint Terminal Attack Controller and they were online with image analysts at the Air Force’s Special Operations Command headquarters in Florida. At every turn the flight crew converted their observations into threat indicators: thus the two SUVs and a pick-up truck became a ‘convoy’, cylindrical objects ‘rifles’, adolescents ‘military-aged males’ and praying a Taliban signifier (‘seriously, that’s what they do’).

After three hours’ surveillance two Kiowa helicopters were called in, and during the attack at least 23 people were killed and more than a dozen wounded. Only after the smoke had cleared did the horrified Predator crew re-cognize the victims as civilians, including women and children.

I’m including a much fuller account in The everywhere war, based on a close reading of the redacted investigative report by Major General Timothy McHale released under a FOI request (the images above are all taken from my Keynote presentation based on the report), and you can also find David McCloud‘s spine-chilling analysis for the LA Times here. But even in this abbreviated form it’s clear that the cascade of (mis)interpretations offered by the flight crew mimics Kevin’s list of ‘signatures’, where some would be categorised as ‘possibly adequate’ and others as ‘inadequate’.

All of these materials relate to air strikes inside a war zone, so that their modalities are different – in Afghanistan remote platforms like the Predator and the Reaper are one element in a networked ‘killing machine’, and they work in close concert with ground forces and conventional strike aircraft – and the legal parameters are not as contentious as those that govern ‘extra-territorial’ strikes in Pakistan, Somalia or Yemen (which are Kevin’s primary concern). But they all raise questions about the evidential and inferential practices that are incorporated into the kill-chain that are clearly capable of wider application and concern.

Those questions raise other issues too. It seems clear, from the examples I’ve given, that to isolate a single platform (the drone) is to contract the scrutiny of military and paramilitary violence that, under the conditions of late modern war, is typically networked. And to determine the legal status of targeted killing must not foreclose on wider political and ethical decisions: to accept late modern war’s avowed reflexivity is too often to equate legality with legitimacy.