This is the third in a series of posts on Grégoire Chamayou‘s Théorie du drone, in which I provide a detailed summary of his argument, links to some of his key sources, and reflections drawn from my soon-to-be-completed The everywhere war (and I promise to return to it as soon as I’ve finished this marathon).

5: Pattern of life analysis

Chamayou begins with the so-called ‘Terror Tuesdays‘ when President Obama regularly approves the ‘kill list’ (or disposition matrix) that authorises ‘personality strikes’ against named individuals: ‘the drones take care of the rest’.

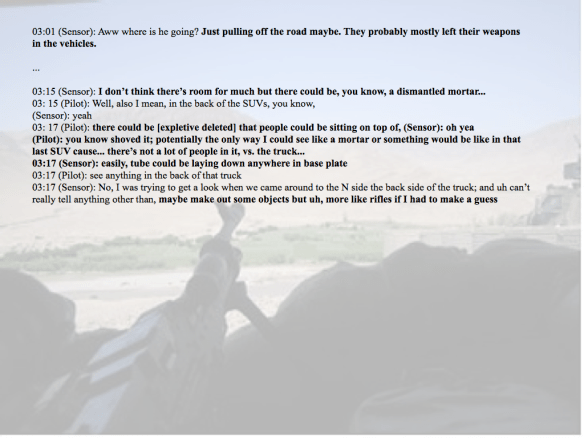

But Chamayou immediately acknowledges that most strikes are ‘signature strikes‘ against individuals whose names are unknown but for whom a ‘pattern of life analysis‘ has supposedly detected persistent anomalies in normal rhythms of activity, which are read as signs (‘signatures’) of imminent threat. I’ve described this as a militarized rhthmanalysis, even a weaponized time-geography, in ‘From a view to a kill’ (DOWNLOADS tab), and Chamayou also notes the conjunction of human geography and social analysis to produce a forensic mapping whose politico-epistemological status is far from secure.

The principal limitation – and the grave danger – lies in mistaking form for substance. Image-streams are too imprecise and monotonic to allow for fine-grained interpretation, Chamayou argues, and supplementing them by equally distant measures, like telephone contacts, often compounds the problem. Hence Gareth Porter‘s objection, which both Chamayou and I fasten upon:

‘The phone numbers and call histories from those phones go into the database which is used to “map the networks.” But the link analysis methodology employed by intelligence analysis is incapable of qualitative distinctions among relationships depicted on their maps of links among “nodes.” It operates exclusively on quantitative data – in this case, the number of phone calls to or visits made to an existing JPEL target or to other numbers in touch with that target. The inevitable result is that more numbers of phones held by civilian noncombatants show up on the charts of insurgent networks. If the phone records show multiple links to numbers already on the “kill/capture” list, the individual is likely to be added to the list.’

This is exactly what happened in the Takhar attack in Afghanistan on 2 September 2010 that I’ve discussed elsewhere, relying on the fine investigative work of Kate Clark, and Chamayou draws attention to it too. The general assumption, as Kate was told by one officer, seems to be that ‘”If we decide he’s a bad person, the people with him are also bad.”

These necro-methodologies raise two questions that Chamayou doesn’t address here.

The first, as Porter notes, is that ‘guilt by association’ is ‘clearly at odds with the criteria used in [international] humanitarian law to distinguish between combatants and civilians.’ You can find a much more detailed assessment of the legality of signature strikes (and what he calls their ‘evidential adequacy’) in Kevin Jon Heller‘s fine essay, ”One hell of a killing machine”: Signature strikes and international law’ [Journal of international criminal justice 11 (2013) 89-119; I discussed a pre-publication version here].

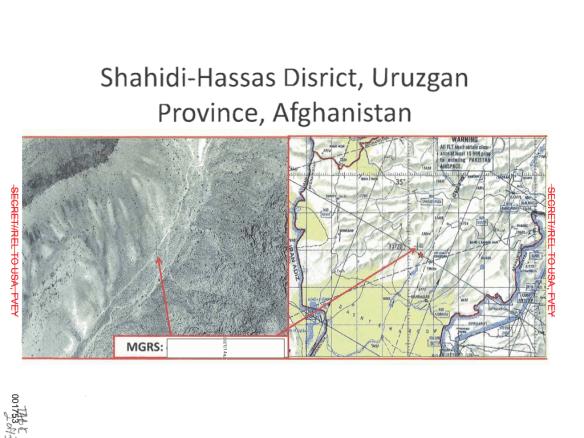

The geo-legal ramifications of these attacks reach far beyond the killing grounds. Earlier this month in the High Court in London one man who lost five relatives in the air strike in Takhar (as you can see on the slide above, on an election convoy) challenged the legality of the alleged involvement of Britain’s Serious and Organised Crimes Agency (SOCA) in drawing up the kill-list, the Joint Prioritized Effects List, used by the military to authorise the attack: more here, here and here. (It was the presence of names on the list that triggered the faulty network analysis).

The second is the imaginary conjured up by the very idea of a ‘pattern of life’ analysis. I’ve written before about the way in which the screen on which the full-motion video feeds from the Predators and Reapers are displayed interpellates those who watch what is happening on the ground from thousands of miles away, and I’ve emphasised that this isn’t a purely optical affair: that it is an embodied, techno-culturally mediated process that involves a series of structured dispositions to view the other as Other (and often dangerous Other). But these dispositions also reside in what we might think of as a grammar of execution. To see what I mean, here is Micah Zenko:

‘Recently, I spoke to a military official with extensive and wide-ranging experience in the special operations world, and who has had direct exposure to the targeted killing program. To emphasize how easy targeted killings by special operations forces or drones has become, this official flicked his hand back over and over, stating: “It really is like swatting flies. We can do it forever easily and you feel nothing. But how often do you really think about killing a fly?”’

Hence, of course, ‘Bugsplat’ [according to Rolling Stone, ‘the military slang for a man killed by a drone strike is “bug splat,” since viewing the body through a grainy-green video image gives the sense of an insect being crushed’], and a host of other predatory terms (see also here) that distinguish between this mere (bare) life and what Judith Butler calls ‘a life that qualifies for recognition’.

But the same result is achieved through the nominally neutral, technical-scientific vocabulary deployed in these strikes. Joseph Pugliese captures the grammar of execution with acute insight in another fine essay, ‘Prosthetics of law and the anomic violence of drones’, [Griffith Law Review 20 (4) (2011) 931-961; you can also find it in his excellent new book State violence and the execution of law]:

But the same result is achieved through the nominally neutral, technical-scientific vocabulary deployed in these strikes. Joseph Pugliese captures the grammar of execution with acute insight in another fine essay, ‘Prosthetics of law and the anomic violence of drones’, [Griffith Law Review 20 (4) (2011) 931-961; you can also find it in his excellent new book State violence and the execution of law]:

‘The term ‘heat signature’ works to reduce the targeted human body to an anonymous heat-emitting entity that merely radiates signs of life. This clinical process of reducing human subjects to purely biological categories of radiant life is further elaborated by the US military’s use of the term ‘pattern of life’…

‘The military term ‘pattern of life’ is inscribed with two intertwined systems of scientific conceptuality: algorithmic and biological. The human subject detected by drone’s surveillance cameras is, in the first scientific schema, transmuted algorithmically into a patterned sequence of numerals: the digital code of ones and zeros. Converted into digital data coded as a ‘pattern of life’, the targeted human subject is reduced to an anonymous simulacrum that flickers across the screen and that can effectively be liquidated into a ‘pattern of death’ with the swivel of a joystick. Viewed through the scientific gaze of clinical biology, ‘pattern of life’ connects the drone’s scanning technologies to the discourse of an instrumentalist science, its constitutive gaze of objectifying detachment and its production of exterminatory violence. Patterns of life are what are discovered and analysed in the Petri dish of the laboratory…

‘Analogically, the human subjects targeted as suspect yet anonymous ‘patterns of life’ by the drones become equivalent to forms of pathogenic life. The operators of the drones’ exterminatory attacks must, in effect, be seen to conduct a type of scientific ethnic cleansing of pathogenic ‘life forms’. In the words of one US military officer: “Our major role is to sanitize the battlefield.”’

Later modern war more generally works through relays of biological-medical metaphors – equally obviously in counterinsurgency, as I’ve described in “Seeing Red” and other essays (DOWNLOADS tab), where the collective enemy becomes a ‘cancer’ that can only be removed by a therapeutic ‘killing to make live’ (including ‘surgical strikes’) – and Colleen Bell has provided an illuminating series of reflections in ‘Hybrid warfare and its metaphors’ [in Humanity 3 (2) (2012) 225-247] and ‘War and the allegory of medical intervention’ [International Political Sociology 6 (3) (2012) 325-8].

This immunitary logic is clearly bio-political, and its speech-acts just as plainly performative, and Pugliese draws the vital conclusion:

‘As mere patterns of pathogenic life, these targeted human subjects effectively are reduced to what Giorgio Agamben would term ‘a kind of absolute biopolitical substance’ that can killed with no concern about the possibility of juridical accountability: they are ‘bare life’ that can be killed with absolute impunity. Anonymous ‘patterns of life’ signify in contradistinction to legally named persons; they exemplify the ‘ontological hygiene’ legislated by US government policy in order to secure the reproduction of the ‘principle of scarcity with respect to agency and personhood’.

‘Situated in this Agambenian context of the extermination of human life with absolute impunity, the Predator drones must be seen as instantiating mobile ‘zones of exception’…’

Which artfully brings me to Chamayou’s next chapter…

6: Kill-box

Chamayou notes that the ‘war on terror’ loosed the dogs of war from their traditional boundaries in time and in space: at once ‘permanent war’ and, as he notes, ‘everywhere war’.

But for Chamayou it is more accurate to speak of the world turned into a ‘hunting ground’ rather than a battlefield, and this matters because two different geographies (his term) are involved. War is defined by combat, he explains, hunting by pursuit. Combat happens where opposing forces engage, but hunting tracks the prey, so that the place of military violence is no longer defined by a delimited space (‘the battlefield’) but by the presence of the enemy-prey who carries with him, as it were, his own mobile halo of a zone of personal hostilities.

To escape, the quarry must make itself undetectable or inaccessible – and the ability to do so depends not only on physical geography (terrain) but also on political and legal geography. For this reason, Chamayou argues, the US has rendered contingent the sovereignty of Pakistan because it (for the most part unwillingly) provides sanctuary to those fleeing across the border from Afghanistan. In such circumstances, what becomes crucial for the hunter is not the military occupation of territory but the ability to control trans-border spaces from a distance through the instantiation of what Eyal Weizman called the politics of verticality that has since captured the attention of Stuart Elden [“Secure the volume: vertical geopolitics and the depth of power”, Political Geography 34 (2013) 35-51], Steve Graham [“Vertical geopolitics: Baghdad and after”, Antipode 36 (1) (2004) 12-23] and others. For this to work, as Weizman shows in the case of occupied Palestine, air power is indispensable.

Chamayou suggests that the US has refined this capacity – in effect, finely calibrated the time and space of the hunt – through the concept of the kill-box. I’m not so sure about this; the lineage of the ‘kill-box’ goes back to the USAF’s ‘target boxes’ [target boxes around An Loc in Vietnam in 1972 are shown below] – and two or three specified ‘boxes’ or ‘Restricted Operating Zones‘ were used to define the Predato’s’ ‘hunting grounds’ over North and South Waziristan that were tacitly endorsed by the Pakistan state.

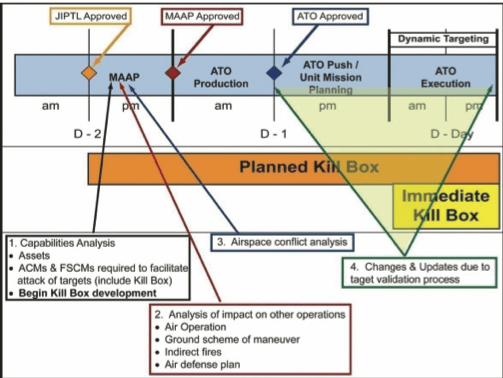

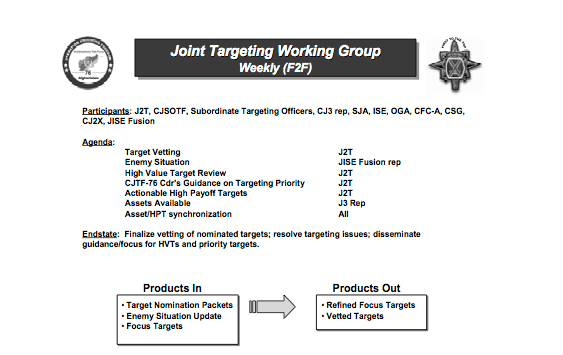

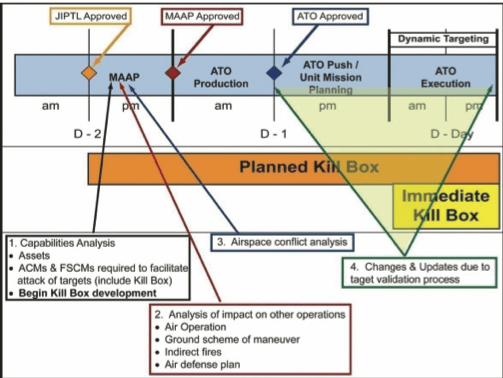

The concept of the ‘kill box’ was formalised as a joint operations doctrine in the 1990s as part of the established targeting cycle: what Henry Nash famously described in another context as ‘the bureaucratization of homicide’. Nash worked for the USAF Air Targets Division in the 1950s and 60s, identifying targets in the USSR for nuclear attack by US Strategic Air Command, but I doubt that Chamayou would dissent from using either the verb or the noun to describe the contemporary, non-nuclear kill-chain. (In a later post I’ll explain how this technical division of labour feeds in to what Chamayou castigates as a ‘setting aside’, a dispersal of responsibility, which functions to separate an action from its consequences: this is aggravated by the remote-split operations in which drones are embedded, and is central to Chamayou’s critique). Here is how the relevant military manuals incorporated the development of the kill box into the targeting cycle in 2009 (ATO = Air Tasking Order):

You can find more on kill-boxes and their operationalisation here.

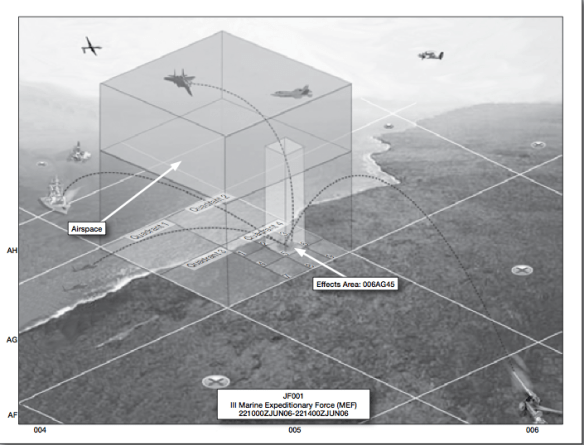

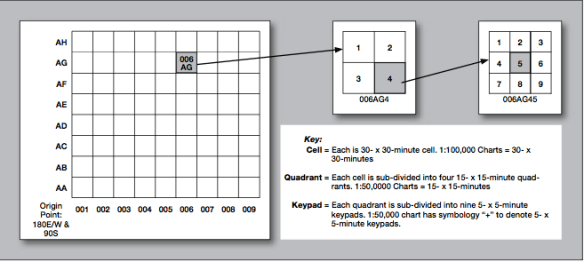

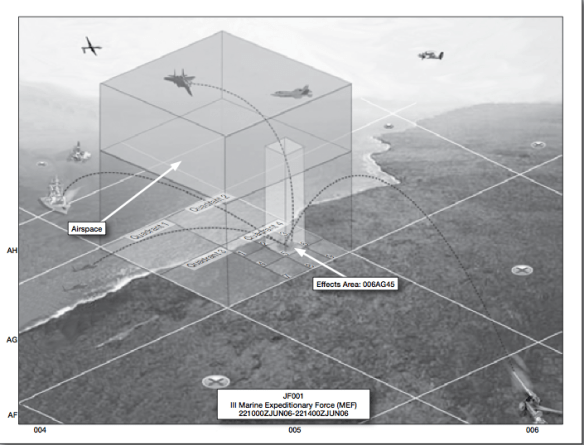

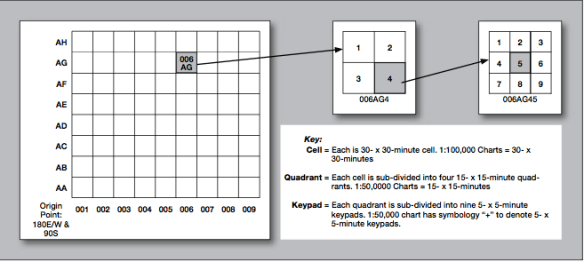

Chamayou doesn’t track the development of the concept, but since then the ‘kill-box’ has been supplanted or at least supplemented by the ‘Joint Fires Area’ as a way of continuing to co-ordinate the deployment of lethal force and allowing targets to be engaged without additional communication. Within the grid of the JFA (shown below, taken from an essay by Major James Mullin on ‘redefining the kill box’) permission to fire in specified cells is established in advance; areas are defined, targeting intervals stipulated, and the time-space cells can be opened and closed as operations proceed.

It is this capacity that Chamayou seizes upon: within the kill box targets can be engaged at will, so that the kill box, he writes, ‘is an autonomous zone of temporary killing’ (cf. the ‘free fire/specified fires zone’ in Vietnam: see my discussion of Fred Kaplan‘s recent essay, ‘The world as a free-fire zone‘).

Chamayou implies that the schema has been further refined in contemporary counterinsurgency and counter-terrorism operations: the fact that the kill-box and its successor allow for dynamic targeting across a series of scales is crucial, he says, because its improvisational, temporary nature permits targeting to be extended beyond a declared zone of conflict. The scale of the JFA telescopes down from the cell shown on the right of the figure below through the quadrant in the centre to the micro-scale ‘keypad’ (sic) on the right.

This is more than a grid, though; the JFA is, in effect, a performative space that authorises, schedules and triggers lethal action. Chamayou: ‘Temporary micro-cubes of lethal exception can be opened anywhere in the world, according to the contingencies of the moment, once an individual who qualifies as a legitimate target has been located.’ Thus, even as the target becomes ever more individuated – so precisely specified that air strikes no longer take the form of the area bombing of cities in World War II or the carpet bombing of the rainforest of Vietnam – the hunting ground becomes, by virtue of the nature of the pursuit and the remote technology that activates the strike, global.

The system I’ve described here is one adopted by the US military, and how far its procedures are used by other agencies outside established conflict zones is unknown to me and doubtless to Chamayou too. Are these micro-cells used to specify individual compounds or rooms, as Chamayou suggests in a thought-experiment? For him, however, it’s the imperative logic that matters, and here Kaplan’s tag-line (above) can provide the key explanatory exhibit: ‘to kill a particular person anywhere on the planet.’ The doubled process of time-space calibration and individuation is what allows late modern war to become the everywhere (but, contra Kaplan, not the anywhere, because specified) war.

On the one side, then, a principle of what Chamayou calls precision or specification: ‘The zone of armed conflict, fragmented into micro-scale kill boxes, reduces itself in the ideal-typical case to the single body of the enemy-prey: the body as the field of battle.’ Yet on the other side, a principle of globalisation or homogenisation: ‘Because we can target our quarry with precision, the military and the CIA say in effect, we can strike them wherever we see fit, even outside a war zone.’

This paradoxical articulation has sparked fierce debates among legal scholars – Chamayou cites Kenneth Anderson, Michael Lewis, and Mary Ellen O’Connell – over whether the ‘zone of armed conflict’ should be geo-centred (as in the conventional battlefield) or target-centred (‘attached to the body of the enemy-prey’). Jurists are thus in the front line of the battle over the extension of the hunting ground, he writes, and ‘applied ontology’ is the ground on which they fight. I’ll have more to say about this on my own account in a later post.

So I was interested to read about photographer Tomas van Houtryve‘s (right) project Blue Sky Days. He begins with an arresting observation with which both James and Josh would be only too familiar:

So I was interested to read about photographer Tomas van Houtryve‘s (right) project Blue Sky Days. He begins with an arresting observation with which both James and Josh would be only too familiar:In October 2012, a drone strike in northeast Pakistan killed a 67-year-old woman picking okra outside her house. At a briefing held in 2013 in Washington, DC, the woman’s 13-year-old grandson, Zubair Rehman, spoke to a group of five lawmakers. “I no longer love blue skies,” said Rehman, who was injured by shrapnel in the attack. “In fact, I now prefer gray skies. The drones do not fly when the skies are gray.”