Last Thursday, the last full day of my visit to Ostrava, Tomas took me to visit the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum in the Polish town of Oswiecim: I’m still trying to come to terms with what I saw and felt.

It was Tomas’s third visit. Last time, he said, it was in the depth of winter, with the ground covered in snow: Auschwitz rendered in the sombre black and white tones we’ve come to expect. On Thursday it all seemed so incongruous: full colour on an unexpectedly sunny day – brilliant blue sky, flowers coming in to bloom and birds singing – and made even more unsettling by the new housing at the edge of the town and the supermarket up the road. To say that is at once to invoke a moral geography of sorts, and in a series of revealing essays Andrew Charlesworth, Robert Guzik, Michal Paskowski and Alison Stenning have documented the controversies that have shaped the site since the establishment of the State Museum in 1947 and the subsequent development before and after the fall of Communism: see ‘”Out of Place” in Auschwitz?’ [in Ethics, place and environment 9 (2) (2006) 149-72] and ‘A tale of two institutions: shaping Oswiecim-Auschwitz’ [in Geoforum 39 (2008) 401-413].

But as soon as we entered the complex a different (though related) series of moral geographies were invoked, also about the dissonance between Auschwitz then and now but more directly bound up with what Chris Keil calls ‘Sightseeing in the mansions of the dead’ [in Social & Cultural Geography 6 (40(2005) 479-494] or what is variously called ‘thanato-tourism’ or ‘dark tourism’: the tourism of death. You can find other fine reflections, following in Keil’s footsteps, in Derek Dalton‘s ‘Encountering Auschwitz: the possibilities and limitations of witnessing/remembering trauma in memorial space’ [in Law, Text, Culture 13 (1) (2009) 187-225] here. Significantly, Dalton argues that current theorising ‘fails to highlight the vital role of the imagination in animating the artefacts and geography of a place and investing them with meaning’.

For the tour is, of course, both pre-scripted (it is surely impossible for most visitors to come to what was the largest extermination camp in Europe without prior expectations and understandings) and scripted (it invites and even licenses a particular range of performances and responses). It takes in Auschwitz I (above), the original site more or less at the centre of Oswiecim that was established in the spring of 1940, and the sprawling open/closed space of Auschwitz II at Birkenau beyond the perimeter established the following year. (Auschwitz III, the labour camp at Monowitz linked to the IG Farben works, is not part of the memorial complex; neither are any of the 40-odd satellite camps).

We started by walking through the gates, their hideous sign Arbeit macht frei silhouetted against the sky, and filed into a series of prison blocks in a silence broken only by the guide’s voice whispering through our headphones and the shuffle of feet on stone and stair.

Inside we saw the collections of suitcases and shoes stripped from those who were murdered inside the camp: signs of movement from all over occupied Europe to the dead stop of the gas chambers. The first, experimental ones killed people in their hundreds; the later ones killed them in their thousands. We will never know the exact number nor all their names, but we do know more than 1,100,000 people were murdered at Auschwitz-Birkenau, around 960,000 of them Jews.

Dalton’s attention was also captured by these collections: a fraction of the total, yet the sheer number of shoes confounded any attempt ‘to posit individual histories’; and even though the suitcases had names and sometimes dates on them, Dalton was numbed by his inability ‘to focus on an individual case; my eye took them in as a mass despite their differences.’ This is a recurrent theme in his essay, but I saw the artefacts differently. As I looked at the collections behind the glass, I started to wonder about the aestheticisation of suffering – about what Keil calls ‘a Hall of Mirrors, a half-world between history and art’ (and in my photographs you can just about see the spectral reflections of the visitors in the glass) – and the ways in which these everyday objects had been turned into a vast still life that none the less could evoke such unutterable terror.

‘I have nothing to say, only to show,’ wrote Walter Benjamin (about his working method). Perhaps that is the best way to apprehend the museum; perhaps, too, this begins to explain Theodor Adorno‘s insistence in Negative Dialectics that ‘to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.’ And yet he later qualified his remark:

‘Perennial suffering has as much right to expression as the tortured have to scream … hence it may have been wrong to say that no poem could be written after Auschwitz.’

He said his objection was to lyric poetry; perhaps, then, we need to reaffirm what Michael Peters [in Educational Philosophy & Theory 44 (2) (2012) 129-32] calls ‘poetry as offence’: a notice inside Dachau declared that anyone found writing or sharing poetry would be summarily executed. For as I trudged across the vast expanse of Birkenau, alongside the railway tracks and the infamous ramp and around the ruins of the gas chambers and crematoria, I began to think that Auschwitz made poetry all the more necessary – as defiant affirmation.

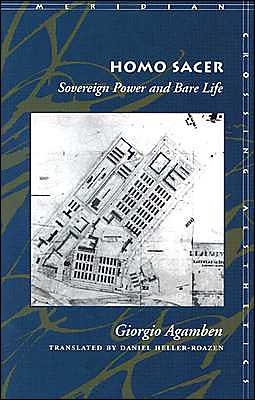

My visit also prompted me to re-visit Giorgio Agamben‘s meditations on Auschwitz in Homo Sacer: sovereign power and bare life and Remnants of Auschwitz: the witness and the archive (which is Homo Sacer III). If you’re not familiar with his work, Andrew Robinson provides a short and accessible summary that speaks directly to his incorporation of the Nazi concentration camp here.

Although the cover of the English-language translation of Homo Sacer (right) shows part of the second master plan for Auschwitz (February 1942), which I’ve reproduced above (and you can find more maps and plans here), Agamben’s discussion is brief, confined to Part III and most of it in §7, where he treats ‘The camp as the nomos of the modern’ and, specifically, as ‘the materialization of the state of exception’ and ‘the most absolute biopolitical space ever to have been realized.’ The plan provided for the expansion of the camp, and van Pelt explains it thus:

Although the cover of the English-language translation of Homo Sacer (right) shows part of the second master plan for Auschwitz (February 1942), which I’ve reproduced above (and you can find more maps and plans here), Agamben’s discussion is brief, confined to Part III and most of it in §7, where he treats ‘The camp as the nomos of the modern’ and, specifically, as ‘the materialization of the state of exception’ and ‘the most absolute biopolitical space ever to have been realized.’ The plan provided for the expansion of the camp, and van Pelt explains it thus:

The left side of the drawing depicts the concentration camp. Its center is the enormous roll-call place, designed to hold thirty thousand inmates. To the south are the barracks of the original camp, a group of brick buildings built in 1916 as a labor exchange center for Polish seasonal workers in Germany. To the east (on the right side), are the SS base and a Siedlung for the married SS men and their families. The center of town includes a hotel and shops.

Given what Agamben subsequently argued about the witness and the archive in Remnants, it is worth remembering that these detailed plans constituted important legal evidence against David Irving‘s notorious dismissal of Auschwitz’s function as an extermination camp as ‘baloney’ (in a Calgary lecture); you can find a detailed account of this early instance of forensic architecture in Robert Jan van Pelt‘s The case for Auschwitz: evidence from the Irving trial (2002) and a suggestive discussion of the plans (including an account in the appendix of the geographical selection of Auschwitz as a ‘central place’: given what we know of Walter Christaller‘s involvement in the spatial planning of Eastern Europe under the Third Reich, I wonder whether this was used in a technical sense?) in van Pelt’s ‘Auschwitz: from architect’s promise to inmate’s perdition’ [in Modernism/Modernity 1 (1) (1994) 80-120], from which I took the plan and explanation above. In our imaginations Auschwitz is full of people, and the plans are naturally as empty of the prisoners as today’s buildings: and yet through van Pelt’s patient, methodical commentary, they become redolent of the horrors they were intended to instil.

In Remnants, Agamben does not attempt to make the plans and stones – the spaces – speak, but he is concerned, in quite another register, to erect ‘some signposts allowing future cartographers of the new [post-Auschwitz] ethical territory to orient themselves.’ Still, I’m left puzzled by the closed geography that captures his attention. The nearest he comes to transcending this is his brief discussion of Hitler’s insistence on the production in central Europe of a volkloser Raum, ‘a space empty of people’, which Agamben glosses as a ‘fundamental biopolitical intensity’ that ‘can persist in every space and through which peoples pass into populations and populations pass into Musselmänner’, the ‘living dead’ of the camps (p. 85). The sequence of transformations evidently stops short – there is, as Agamben says himself, a ‘central non-place’ at the heart of Auschwitz: the gas chamber – but Agamben’s reluctance to go there is in part a product of his interest in bare life and in part a product of an argument directed towards elucidating the position of the witness (even then his selection and examination of witnesses is, as Jeffrey Mehlman shows, strikingly arbitrary). It’s a profound absence, but even Agamben’s abbreviated sequence shows that to make sense of Auschwitz-Birkenau and that still space at its centre you have to turn outwards and imagine spaces of exception that spiral far beyond and converge upon the dread confines of the camp: the contraction of the spaces of everyday life, the confinement of the ghettoes, the transit camps, the railway lines snaking across the dark continent. Their absence from Remnants has acutely political and ethical consequences, because it threatens to turn the act of witnessing into a purified aesthetic act; the best discussion of this that I know is J.M. Bernstein‘s ‘Bare life, bearing witness: Auschwitz and the pornography of horror’ [in parallax 10 (1) (2004) pp. 2-16], which I drew on in my discussion of Agamben and Auschwitz in ‘Vanishing points’. Paolo Giacarria and Claudio Minca have more recently emphasised in their ‘Topographies/topologies of the camp’ [in Political geography 30 (2011) 3-12] that

In Remnants, Agamben does not attempt to make the plans and stones – the spaces – speak, but he is concerned, in quite another register, to erect ‘some signposts allowing future cartographers of the new [post-Auschwitz] ethical territory to orient themselves.’ Still, I’m left puzzled by the closed geography that captures his attention. The nearest he comes to transcending this is his brief discussion of Hitler’s insistence on the production in central Europe of a volkloser Raum, ‘a space empty of people’, which Agamben glosses as a ‘fundamental biopolitical intensity’ that ‘can persist in every space and through which peoples pass into populations and populations pass into Musselmänner’, the ‘living dead’ of the camps (p. 85). The sequence of transformations evidently stops short – there is, as Agamben says himself, a ‘central non-place’ at the heart of Auschwitz: the gas chamber – but Agamben’s reluctance to go there is in part a product of his interest in bare life and in part a product of an argument directed towards elucidating the position of the witness (even then his selection and examination of witnesses is, as Jeffrey Mehlman shows, strikingly arbitrary). It’s a profound absence, but even Agamben’s abbreviated sequence shows that to make sense of Auschwitz-Birkenau and that still space at its centre you have to turn outwards and imagine spaces of exception that spiral far beyond and converge upon the dread confines of the camp: the contraction of the spaces of everyday life, the confinement of the ghettoes, the transit camps, the railway lines snaking across the dark continent. Their absence from Remnants has acutely political and ethical consequences, because it threatens to turn the act of witnessing into a purified aesthetic act; the best discussion of this that I know is J.M. Bernstein‘s ‘Bare life, bearing witness: Auschwitz and the pornography of horror’ [in parallax 10 (1) (2004) pp. 2-16], which I drew on in my discussion of Agamben and Auschwitz in ‘Vanishing points’. Paolo Giacarria and Claudio Minca have more recently emphasised in their ‘Topographies/topologies of the camp’ [in Political geography 30 (2011) 3-12] that

‘what will eventually become the most infamous extermination camp was … not located in a void; quite the contrary, it was fully embedded within the broader spatialities and territorialities that were implemented by the Nazi imperial project.’

I sketched some of these geographies in my entry on holocaust in the Dictionary of Human Geography, and for me all this means that the immediate struggle during my visit to Auschwitz-Birkenau was an effort of the imagination: to focus in on the individual lives lost in the mass murder while simultaneously panning out to the wider spaces of terror set in motion far beyond and, crucially, constitutive of the site of the camp itself.

But the ongoing, far greater conundrum is to understand how it all was possible: how could people do such things? Agamben himself portrays this as the ‘incorrect’, even ‘hypocritical’ question…. As with his more general argument about homo sacer, responsibility plainly does not lie solely with those who used political and legal artifice to put so many people to death; mass murder on an industrial scale, surely the most exorbitant of all the grim termini of Fordist war, required more than Hitler and Himmler. Neither can the willingness of so many men and women to be party to these murders be explained by their “following orders” and being “fearful of punishment”, a putrid defence that most historians have exposed as a lie. What is so extraordinary, after all, is the way in which, under general directives, so much was left to local improvisation and ‘ordinary’ functionaries. The ‘prison within the prison’, Auschwitz’s Block 11, is an exemplary instance: here punishments were devised for people who were already destined for death. I have no answer, but I do think that the key is not only in turning ‘ordinary’ people into ‘functionaries’ but also in luring and licensing the transformation of base imaginations into physical realities.

But the ongoing, far greater conundrum is to understand how it all was possible: how could people do such things? Agamben himself portrays this as the ‘incorrect’, even ‘hypocritical’ question…. As with his more general argument about homo sacer, responsibility plainly does not lie solely with those who used political and legal artifice to put so many people to death; mass murder on an industrial scale, surely the most exorbitant of all the grim termini of Fordist war, required more than Hitler and Himmler. Neither can the willingness of so many men and women to be party to these murders be explained by their “following orders” and being “fearful of punishment”, a putrid defence that most historians have exposed as a lie. What is so extraordinary, after all, is the way in which, under general directives, so much was left to local improvisation and ‘ordinary’ functionaries. The ‘prison within the prison’, Auschwitz’s Block 11, is an exemplary instance: here punishments were devised for people who were already destined for death. I have no answer, but I do think that the key is not only in turning ‘ordinary’ people into ‘functionaries’ but also in luring and licensing the transformation of base imaginations into physical realities.

Note: There’s a vast specialist and a general literature on Auschwitz, but for a book that brilliantly bridges the two I recommend Laurence Rees‘s authoritative and accessible Auschwitz: the Nazis and the final solution, also published as Auschwitz: a new history (available in a Kindle edition).

ADDENDUM: This post continues to attract many readers several years after I wrote it, so I should probably add that I’ve since become even more critical of Agamben’s views on the exception. If we think of a space of exception as one in which groups of people are knowingly and deliberately exposed to death through the removal of ordinary legal protections then the conflict zone is surely a paradigmatic case (and its indistinction has become ever clearer [sic] since the ‘deconstruction of the battlefield’ from the First World War on); but this is not a legal void, since the right of combatants to kill one another – and the concomitant obligation to afford at least minimal protection to civilians – is regulated by international law (Agamben’s concern in State of exception is entirely with the suspension of national laws). It is sadly the case that the invocation of international law as anything other than a rhetorical gesture has become all too common, but the failure to respect its norms or to sanction those responsible for its transgression has not reduced civilians crouching under the bombs or caught in the cross-fire to ‘bare life’. For an indication of what I have in mind, see ‘The Death of the Clinic‘.

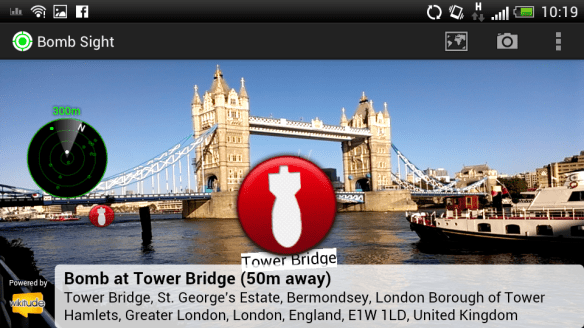

![London Blitz mapped [Guardian]](https://geographicalimaginations.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/london-blitz-mapped-guardian.png?w=584)