Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer has published an extended critique of Grégoire Chamayou‘s Théorie du drone at La vie des idées under the title ‘Ideology of the drone’. Some of the essays from that site are eventually translated into English and appear on the mirror site Books & Ideas, but I have no idea when or even whether this one will be, so I thought it would be helpful to provide a summary.

Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer has published an extended critique of Grégoire Chamayou‘s Théorie du drone at La vie des idées under the title ‘Ideology of the drone’. Some of the essays from that site are eventually translated into English and appear on the mirror site Books & Ideas, but I have no idea when or even whether this one will be, so I thought it would be helpful to provide a summary.

First, some background. Vilmer has travelled via Montréal, Yale and War Studies at King’s College London to his present position at Sciences Po in Paris, where he teaches ethics and the law of war; he also teaches at the military academy at Saint-Cyr, and is a policy adviser on security issues to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Vilmer is the author of more than a dozen books, of which La Guerre au nom de l’humanité : tuer ou laisser mourir (2012) is probably the best known. If you’re not familiar with his work, here’s an English-language interview with him about La Guerre au nom de l’humanité via France 24 and the Daily Motion:

I should note, too, that Vilmer’s critique trades in part on an essay published earlier this year, ‘Légalité et légitimité des drones armés’ [‘Legality and legitimacy of armed drones’], in Politique étrangère 3 (2013) 119-32, in which he rehearses a number of criticisms of Chamayou. There Vilmer insists that the use of drones is perfectly compatible with the principles of international humanitarian law (this is about principle not practice, though, and he doesn’t address the implications of international human rights law which many critics and NGOs believe is the operative body of law for drone strikes outside war zones, like those carried out by the US in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan).

I should note, too, that Vilmer’s critique trades in part on an essay published earlier this year, ‘Légalité et légitimité des drones armés’ [‘Legality and legitimacy of armed drones’], in Politique étrangère 3 (2013) 119-32, in which he rehearses a number of criticisms of Chamayou. There Vilmer insists that the use of drones is perfectly compatible with the principles of international humanitarian law (this is about principle not practice, though, and he doesn’t address the implications of international human rights law which many critics and NGOs believe is the operative body of law for drone strikes outside war zones, like those carried out by the US in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan).

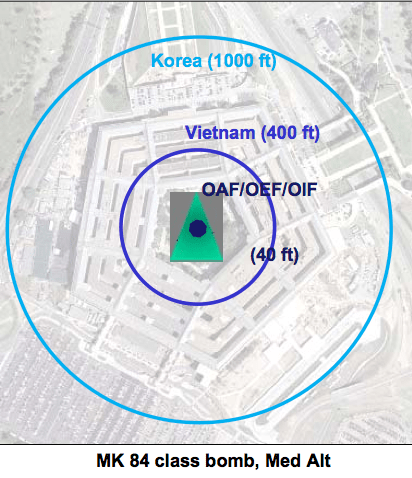

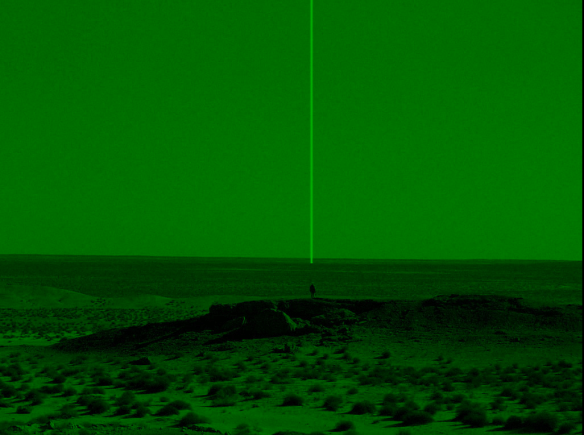

He also has no time for critics who turn the distance between the drone operator and the target into a moral absolute (though I don’t think Chamayou does that at all: instead, as I tried to show previously, he provides a nuanced discussion of the concept of distance). Still, Vilmer is right to insist that the history of modern war is the history of killing the enemy from ever greater distances, and those who cling to the ‘nobility’ of hand-to-hand fighting are blind to an historical record reaching back over centuries. If distance is a ‘moral buffer’, this is hardly unique to today’s remote operations, where in any case the greater physical distance is counterbalanced by a compression of what Vilmer calls ‘epistemic distance’ through the real-time full-motion video feeds transmitted from the drone. The difference between the crew of a Lancaster bomber over Germany and the drone operator controlling an aircraft over Afghanistan is that the latter sees his victim. And if conducting strikes by computer is ‘dehumanising’, the machetes used at close quarters in the Rwandan genocide were hardly less so. What is more, Vilmer suggests, those video feeds are not only remote witnesses of the target; there is an important sense in which they also function as remote witnesses of the crew, providing a vital record for any subsequent military-judicial investigation and thus inviting and even institutionalising a regularised monitoring of ‘the conduct of conduct’.

Now to the extended critique of Chamayou. Vilmer notes that Théorie du drone follows directly from Chamayou’s previous book, Chasses à l’homme [Manhunts], and in fact that’s his main problem with it: he says that Théorie reduces the function of drones to ‘hunting’, specifically to the US campaign of targeted killing, and identifies the one so closely with the other that the force of his analysis is blunted. Vilmer thinks this is playing to the crowd: there is a considerable audience opposed to the use of drones who find Chamayou’s arguments convincing because they confirm their own views.

Now to the extended critique of Chamayou. Vilmer notes that Théorie du drone follows directly from Chamayou’s previous book, Chasses à l’homme [Manhunts], and in fact that’s his main problem with it: he says that Théorie reduces the function of drones to ‘hunting’, specifically to the US campaign of targeted killing, and identifies the one so closely with the other that the force of his analysis is blunted. Vilmer thinks this is playing to the crowd: there is a considerable audience opposed to the use of drones who find Chamayou’s arguments convincing because they confirm their own views.

Indeed, Chamayou makes it plain that one of his express intentions is to provide the critics with useful tools to advance their political work. Yet at the same time he presents Théorie as a philosophical investigation – and it is that, Vilmer concedes, erudite and at times brilliant – but in his view the objective is less to provide understanding than to provoke indignation. In fact, Chamayou has said in press interviews that what provoked him in the first place was the sight of philosophers collaborating with the military – and Vilmer freely admits to being one of them (though in France rather than the United States or Israel).

It’s important to examine the practice of targeted killing, Vilmer agrees, because it raises crucial ethical and legal questions. But it’s also important not to confuse the ends with the means. As I’ve noted in my own commentaries on Théorie, there are other ways of carrying out targeted killing (as Russian dissidents on the streets of London or Iranian scientists on the streets of Tehran have discovered to their cost) and there are many other military uses for drones. Targeted killing gets the most publicity because it’s so controversial, Vilmer argues, but it’s far less important than the provision of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (though ISR is central to lethal strikes carried out by conventional aircraft and ground troops too).

Vilmer is breezily confident about the use of drones in war-zones, where he says they are no more problematic than any other observation platform or weapons system. Contrary to Chamayou’s assertion that drones only save ‘our’ lives, Vilmer insists that they have saved the lives of others – ‘their’ lives – in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and Mali. Yet Chamayou isn’t interested in these cases; instead his ‘theory of the drone’ reduces its role to CIA-directed targeted killings in Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia, which Vilmer complains is like calling a book on Russian cyber-attacks Theory of the computer.

That said, he thinks Chamayou’s critique of signature strikes is ‘excellent’, and he deeply regrets the migration of the American campaign away from ‘personality strikes’ against High Value Targets. The widening of the target lists and the ‘industrialisation’ of targeted killing deserves condemnation – and Vilmer notes that the Obama administration, responsible for ramping up the attacks, has since cut them back in response to criticisms – but in his view this only shows that Predators and Reapers ‘have been used in an imprecise way’ not that they are intrinsically less accurate than other systems.

That said, he thinks Chamayou’s critique of signature strikes is ‘excellent’, and he deeply regrets the migration of the American campaign away from ‘personality strikes’ against High Value Targets. The widening of the target lists and the ‘industrialisation’ of targeted killing deserves condemnation – and Vilmer notes that the Obama administration, responsible for ramping up the attacks, has since cut them back in response to criticisms – but in his view this only shows that Predators and Reapers ‘have been used in an imprecise way’ not that they are intrinsically less accurate than other systems.

When Chamayou seeks to show, to the contrary, that drones are ‘inhumane’ he advances two arguments that Vilmer flatly rejects. (I have to say that I think Chamayou’s arguments are considerably more subtle than Vilmer allows: see here and here). The first – the claim that ‘unmanned’ aircraft are by definition ‘inhuman’ – he dismisses as sophistry, not because each operation involves almost 200 people but because the bombers that destroyed Hamburg and levelled Dresden were ‘manned’: he says that Chamayou would hardly describe the results of their missions as ‘humane’. The second – that machines dedicated to killing cannot be ‘humane’ – is an absolutism that doesn’t engage with those (like Vilmer) who argue that some weapons are more humane than others. That, after all, is precisely why some weapons are banned by international law. And unlike Chamayou, Vilmer insists that drones allow for a greater degree of compliance with principles of distinction because they are more than weapons systems: they also provide enhanced ISR.

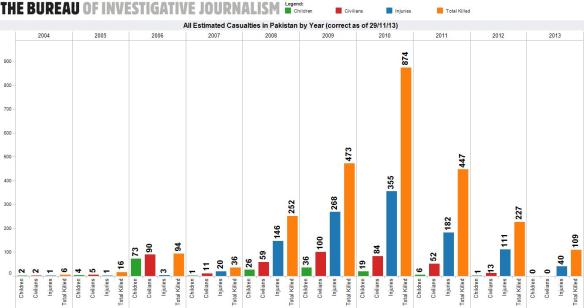

Vilmer agrees that it is wrong to compare drone strikes with bombing missions in the Second World War, Korea or Vietnam, but he disagrees with the contemporary alternative canvassed by Chamayou: ground troops armed with grenades. In the case of Pakistan, Yemen or Somalia this isn’t a realistic option, he argues, and in the absence of drones the only alternative would be a Kosovo-like bombing campaign or a rain of Tomahawk missiles – neither of which would be as accurate as a Hellfire missile. But this is to substitute one absolutism for another. Hellfire missiles are not confined to Predators and Reapers but are also carried by conventional strike aircraft and attack helicopters; and in any case cruise missiles have been launched from US Naval vessels to attack targets in Yemen, and Special Forces have been deployed on the ground in all three killing fields. Perhaps more to the point, however, Vilmer knows very well that conventional operations involving ground troops do not typically minimise civilian casualties. He points to the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq as reasons for Obama’s greater reliance on remote operations and a ‘lighter footprint’, and he also emphasises (as Chamayou does not) the casualties caused by Pakistan’s own military operations in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (see my discussions here and here).

This last brings Vilmer to a key objection, which is that Chamayou provides no detailed discussion of the reasons behind the US drone strikes. It’s not enough to attribute them to American imperialism tout court, he insists, because this is a reductive argument that turns terrorists and insurgents into freedom fighters and fails to acknowledge let alone analyse the real dangers posed, both locally and trans-nationally, by al-Qaeda and its associates. Théorie doesn’t simply ‘disappear’ the terrorists, Vilmer writes, it turns them into victims: like so many rabbits put back in the magician’s hat. The imagery is almost Chamayou’s – he claims that ‘one no longer fights the enemy, one eliminates them like rabbits’ – but Vilmer prefers another one. He says that Chamayou’s talk of the predator (or Predator) advancing, the prey fleeing, makes it seem as though the drones are targeting Bambi’s mother…

It’s another clever phrase (and Vilmer excels in them), but I think Chamayou is much more sensitive to civilian casualties – and to the plight of all those innocents living under the perpetual threat of attack – than Vilmer. There are snares and dangers out there, to be sure; but there are also an awful lot of Bambis and their mothers.

Finally, Vilmer turns to France’s decision to buy Reapers, which Chamayou contends has caused no outcry in France only because the public is badly informed about drones. On the contrary, Vilmer replies: it’s because they can tell the difference between buying the technology and using it like the Americans. Vilmer has much more to say about this in a recent open access interview in Politique étrangère, where he explains that the Air Force had deployed four unarmed drones, a version of Israel’s Heron called the Harfang, in Afghanistan, Libya and Mali, but that from the end of this year France will start to take delivery of 12 MQ-9 Reapers: these too will be unarmed. He also speculates about the future development of drones. Among other things, there will be a lot more of them (so he does worry about their proliferation); he also thinks they will be faster and stealthier, more lethal and more autonomous, and that they will fly in swarms. He also believes that aircraft of the future will increasingly be produced in two versions: either conventional operations with pilots onboard or remote operations with pilots in a Ground Control Station.

Please bear in mind that this is only a summary of Vilmer’s critique, which is vulnerable to its own simplifications and caricatures, though I obviously haven’t been able to keep entirely silent. But I’ll reserve a fuller engagement until I’ve finished my own extended commentary on Théorie du drone.