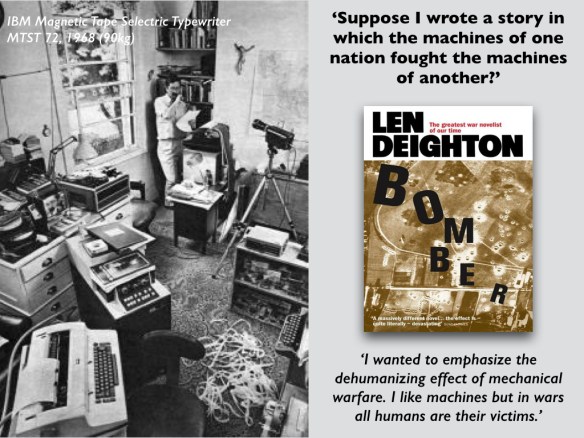

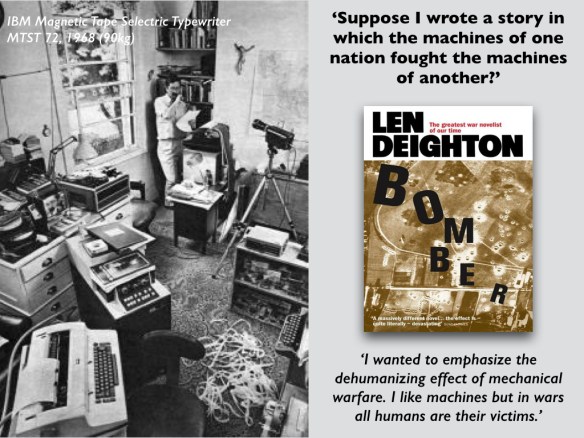

I began the first of my Tanner Lectures – Reach from the Sky – with a discussion of the machinery of bombing, and I started by describing an extraordinary scene: the window of a Georgian terrace house in London being popped out – but not by a bomb. The year was 1968, and the novelist Len Deighton was taking delivery of the first word-processor to be leased (not even sold) to an individual.

As Matthew Kirschenbaum told the story in Slate:

The IBM technician who serviced Deighton’s typewriters had just heard from Deighton’s personal assistant, Ms. Ellenor Handley, that she had been retyping chapter drafts for his book in progress dozens of times over. IBM had a machine that could help, the technician mentioned. They were being used in the new ultramodern Shell Centre on the south bank of the Thames, not far from his Merrick Square home.

A few weeks later, Deighton stood outside his Georgian terrace home and watched as workers removed a window so that a 200-pound unit could be hoisted inside with a crane. The machine was IBM’s MTST (Magnetic Tape Selectric Typewriter).

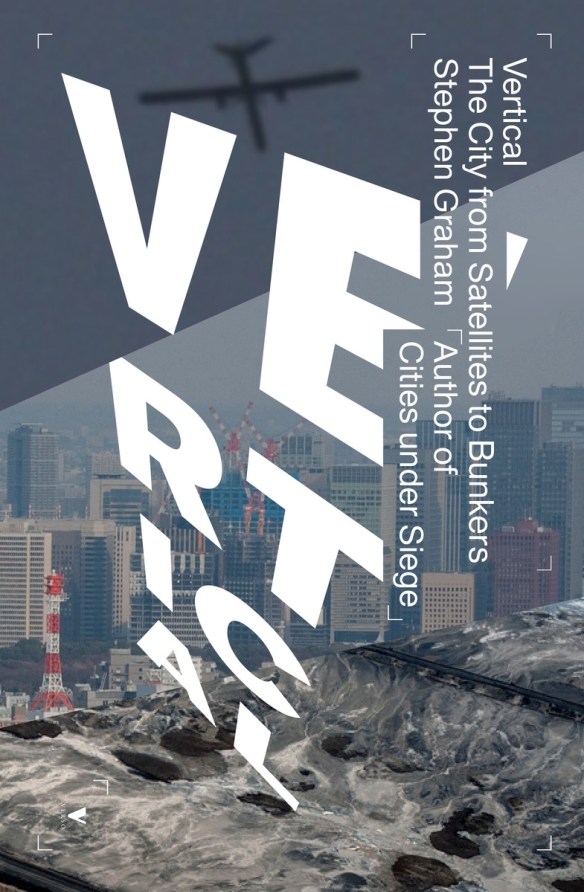

It was a lovely story, because the novel Deighton was working on – almost certainly the first to be written on a word-processor – was his brilliant account of bombing in the Second World War, Bomber. It had started out as a non-fiction book (and Deighton has published several histories of the period) but as it turned into a novel the pace of research never slackened.

Deighton recalls that he had shelved his original project until a fellow writer, Julian Symons, told him that he was ‘the only person he could think of who actually liked machines’:

I had been saying that machines are simply machines… That conversation set me thinking again about the bombing raids. And about writing a book about them. The technology was complex but not so complex as to be incomprehensible. Suppose I wrote a story in which the machines of one nation fought the machines of another? The epitome of such a battle must be the radar war fought in pitch darkness. To what extent could I use my idea in depicting the night bombing war? Would there be a danger that such a theme would eliminate the human content of the book? The human element was already a difficult aspect of writing such a story.

And so Bomber was born.

The novel describes the events surrounding an Allied attack during the night of 31 June (sic) 1943 – the planned target was Krefeld, but the town that was attacked, a ‘target of opportunity’, was ‘Altgarten’. And like the bombing raid, it was a long haul. As Deighton explained:

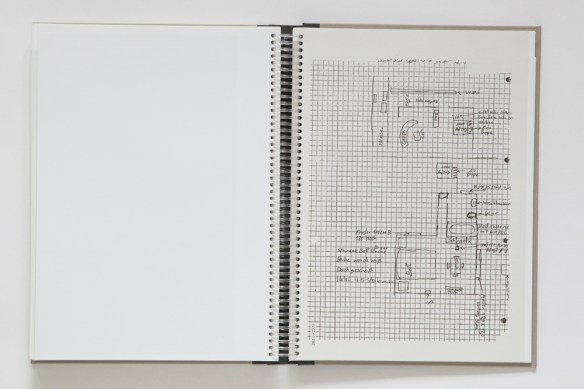

I am a slow worker so that each book takes well over a year—some took several years—and I had always ‘constructed’ my books rather than written them. Until the IBM machine arrived I used scissors and paste (actually Copydex one of those milk glues) to add paras, dump pages and rearrange sections of material. Having been trained as an illustrator I saw no reason to work from start to finish. I reasoned that a painting is not started in the top left hand corner and finished in the bottom right corner: why should a book be put together in a straight line?

Deighton’s objective, so he said, was ‘to emphasize the dehumanizing effect of mechanical warfare. I like machines but in wars all humans are their victims.’

I pulled all this together in this slide:

I then riffed off Deighton’s work in two ways.

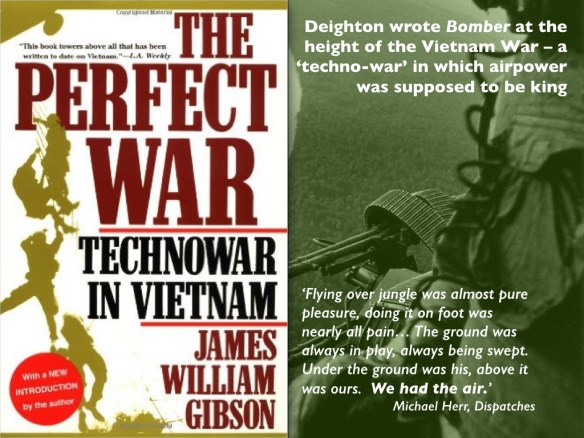

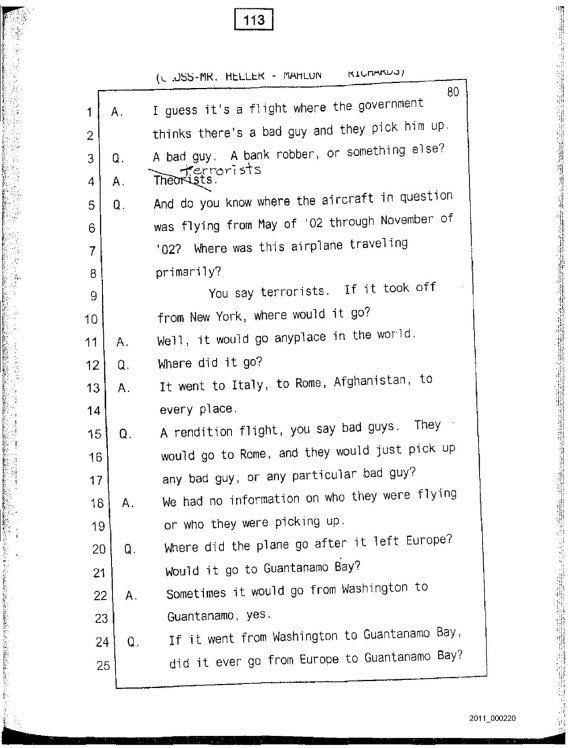

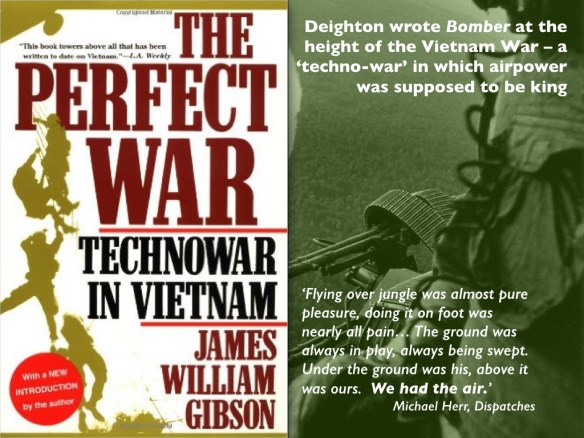

First, I noted that Bomber was written at the height of the Vietnam War, what James Gibson calls ‘techno-war’:

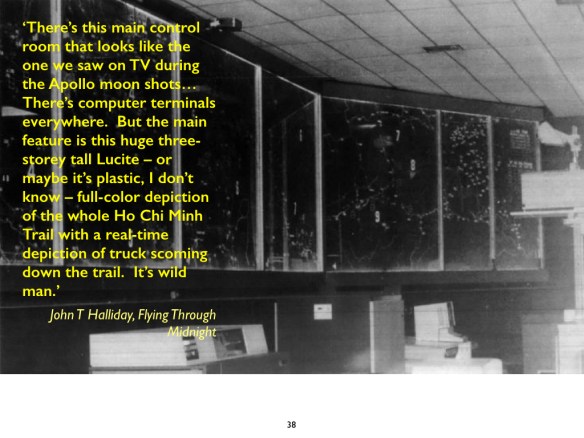

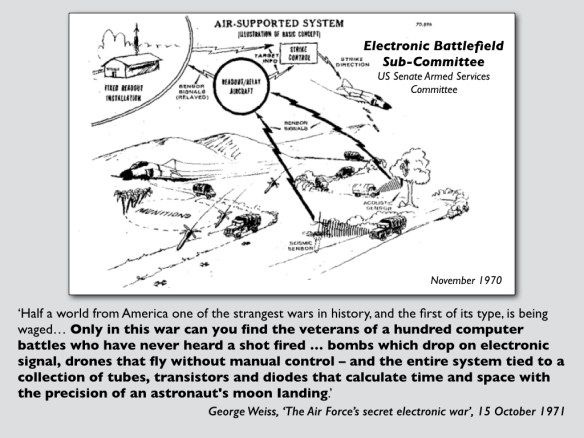

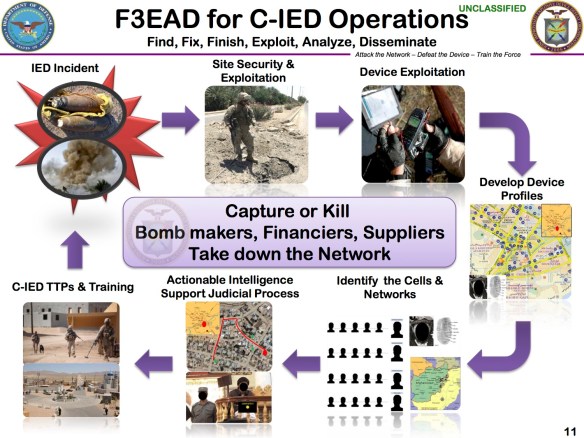

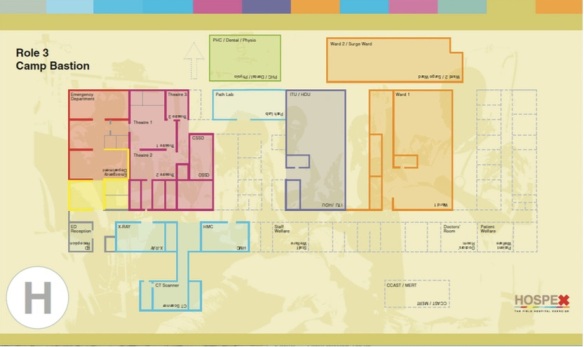

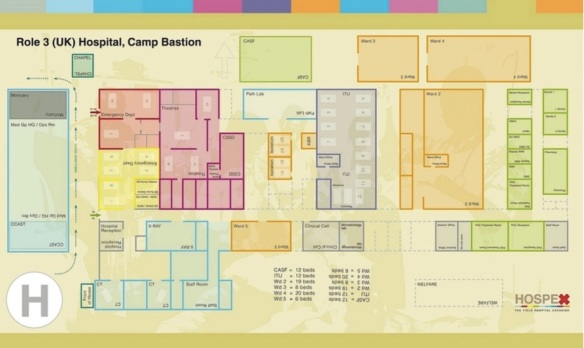

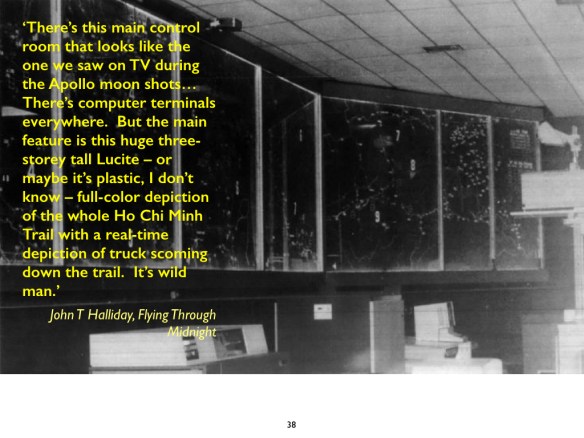

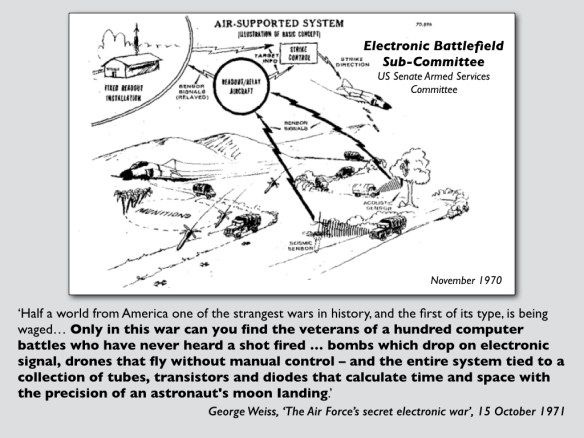

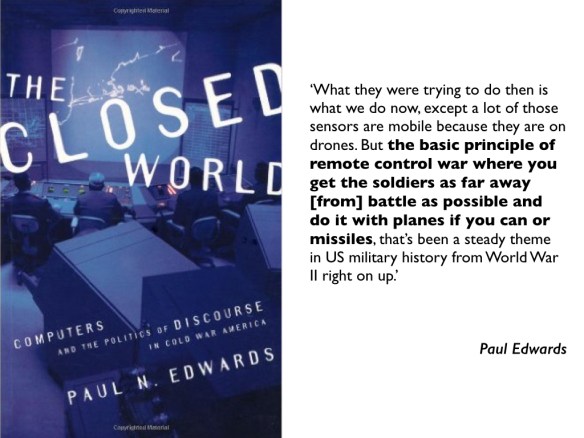

I focused on the so-called ‘electronic battlefield’ that I had discussed in detail in ‘Lines of descent’ (DOWNLOADS tab), and its attempt to interdict the supply lines that snaked along the Ho Chi Minh Trail by sowing it with sensors and automating bombing:

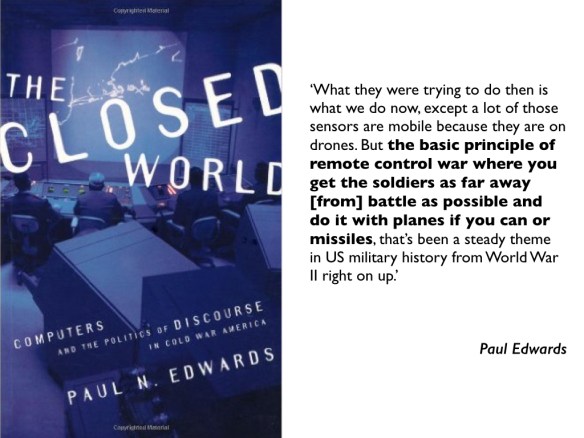

The system was an expensive failure – technophiles and technophobes alike miss that sharp point – but it prefigured the logic that animates today’s remote operations:

Second – in fact, in the second lecture – I returned to Bomber and explored the relations between Deighton’s ‘men and machines’. There I emphasised the intimacy of a bomber crew in the Second World War (contrasting this with the impersonal shift-work that characterises today’s crews operating Predators and Reapers). ‘In the air’, wrote John Watson in Johnny Kinsman, ‘they were component parts of a machine, welded together, dependent on each other.’ This was captured perfectly, I think, in this photograph by the inimitable Margaret Bourke-White:

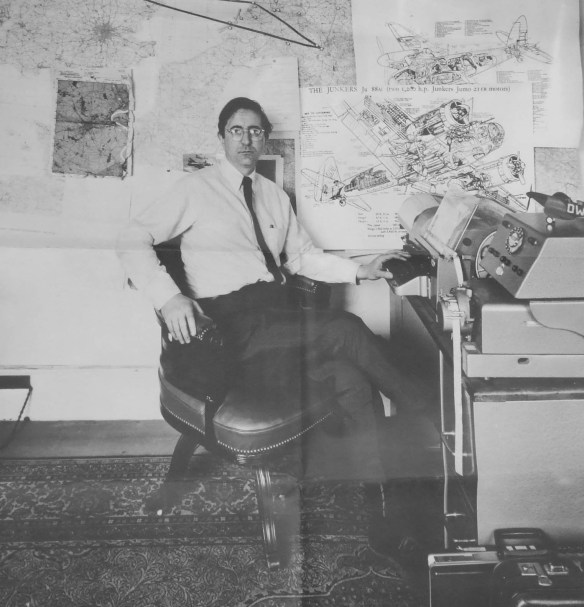

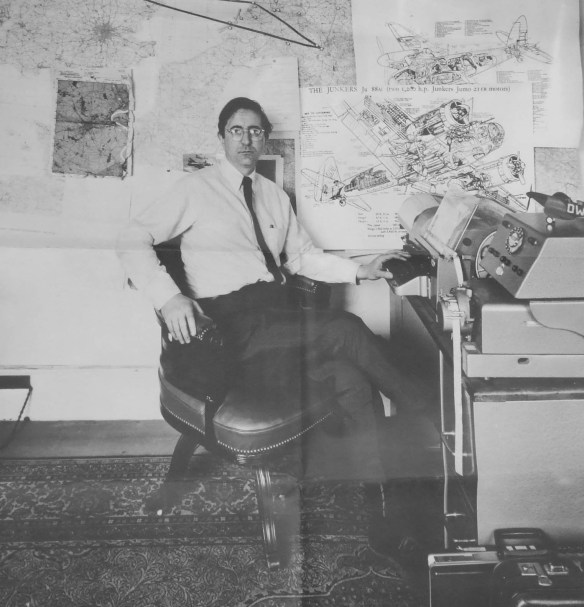

Much to say about the human, the machine and the cyborg, no doubt, but what has brought all this roaring back is another image of the entanglements between humans and machines that returns me to my starting-point. In a fine essay in The Paris Review, ‘This faithful machine‘, Matthew Kirschenbaum revisits the history of word-processing. It’s a fascinating read, and it’s headed by this photograph of Len Deighton working on Bomber in his study:

Behind him you can see giant cut-away diagrams of British and German bombers, and on the left a Bomber Command route map to ‘the target for tonight’ (the red ribbon crossing the map of Europe), and below that a target map. ‘Somber things,’ he called them in Bomber:

‘inflammable forest and built-up areas defined as grey blocks and shaded angular shapes. The only white marks were the thin rivers and blobs of lake. The roads were purple veins so that the whole thing was like a badly bruised torso.’

More on all that in my ‘Doors into nowhere’ (DOWNLOADS tab), and much more on the history of word-processign in Matthew’s Track Changes: A Literary History of Word Processing just out from Harvard University Press:

The story of writing in the digital age is every bit as messy as the ink-stained rags that littered the floor of Gutenberg’s print shop or the hot molten lead of the Linotype machine. During the period of the pivotal growth and widespread adoption of word processing as a writing technology, some authors embraced it as a marvel while others decried it as the death of literature. The product of years of archival research and numerous interviews conducted by the author, Track Changes is the first literary history of word processing.

Matthew Kirschenbaum examines how the interests and ideals of creative authorship came to coexist with the computer revolution. Who were the first adopters? What kind of anxieties did they share? Was word processing perceived as just a better typewriter or something more? How did it change our understanding of writing?

Track Changes balances the stories of individual writers with a consideration of how the seemingly ineffable act of writing is always grounded in particular instruments and media, from quills to keyboards. Along the way, we discover the candidates for the first novel written on a word processor, explore the surprisingly varied reasons why writers of both popular and serious literature adopted the technology, trace the spread of new metaphors and ideas from word processing in fiction and poetry, and consider the fate of literary scholarship and memory in an era when the final remnants of authorship may consist of folders on a hard drive or documents in the cloud.

And, as you’d expect, it’s available as an e-book.