Anyone who has read Washington Post journalist Rajiv Chandrasekaran‘s Imperial Life in the Emerald City: Inside Iraq’s Green Zone (Vintage, 2006) or his Little America: the war within the war in Afghanistan (Knopf, 2012) – and even those who haven’t – will enjoy David Johnson‘s interview with him at the Boston Review.

In it Chandrasekaran draws some illuminating parallels (in two words: ‘strategic failure’) and provocative contrasts between the two campaigns:

In it Chandrasekaran draws some illuminating parallels (in two words: ‘strategic failure’) and provocative contrasts between the two campaigns:

I surely saw far more imperialistic overtones in Iraq than in Afghanistan. The bulk of my narrative in Little America focuses on how the Obama administration attempted to deal with the situation there. Though they pursued, in my view, a flawed strategy, they did approach it with some degree of humility. I certainly wouldn’t ascribe imperialist aims to the United States in Afghanistan from 2009 onward or even before that. I don’t ever think that we really went about it in that way. Whereas, one can look at what occurred in Iraq, particularly in the early years, and come to a very different conclusion.

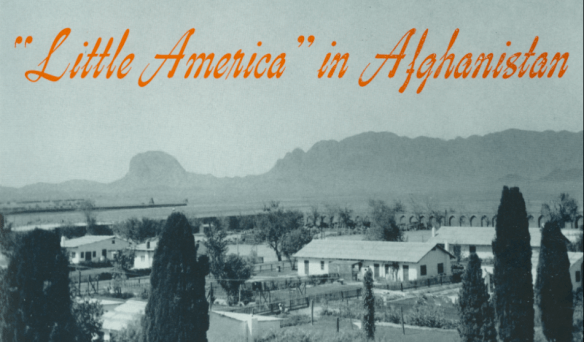

Chandrasekaran has some important things to say about the so-called ‘development-security’ nexus, not least through a comparison with USAID projects in Helmand in the 1950s. You know he’s on to something when Max Boot dismisses it: that was when local people started calling the area ‘Little America’, but Boot says that’s ‘far removed’ from the present situation. I think Chandresekaran is right; certainly when I was writing the Afghanistan chapters of The colonial present I learned much from Nick Cullather, ‘Damming Afghanistan: modernization in a buffer state’, Journal of American History 89 (2002) 512-37 – a preliminary study researched and written, as he notes, ‘between the beginning of the bombing campaign in late September and the mopping up [sic] of Taliban resistance around Tora Bora in early December 2001.’ Chandresekaran relied on an early version of the essay, and you can now access a later version as Chapter 4 [‘We shall release the waters’] of Cullather’s The hungry world: America’s Cold War battle against poverty in Asia (Harvard, 2010). Little America loops back to where it began, with one farmer – whose father had been drawn to Helmand by the promise of the new dam – telling Chandresekaran: ‘We are waiting for you Americans to finish what you started.’

This is also the epitaph for what Chandrasekaran sees as ‘the good war turned bad’: too few people were invested in seeing it through. In the book he paints vivid portraits of those on the ground who were committed to staying the course, but concludes that they were the exception:

‘It wasn’t Obama’s war, and it wasn’t America’s war.

‘For years we dwelled on the limitations of the Afghans. We should have focused on ours.’

Not surprisingly, Boot doesn’t care for Chandrasekaran’s take on counterinsurgency either, though his own view is spectacularly devoid of the historical and geographical sensitivity that distinguishes Little America. Boot describes COIN as ‘just the accumulated wisdom of generations of soldiers of many nationalities who have fought guerrillas’ (really) and insists that it (singular) ‘has worked in countries as diverse as the Philippines (during both the war with the U.S. in 1899-1902 and the Huk Rebellion in 1946-54), Malaya, El Salvador, Northern Ireland, Colombia and Iraq.’ Perhaps it all depends on what you mean by ‘worked’…

In fact, Chandrasekaran focuses relentlessly on the work of counterinsurgency. Little America begins with the sequestered imagery of ‘America abroad’ that will be familiar to readers of Imperial Life in the Emerald City –

– but soon moves far beyond such enclaves to document operations on the ground. In the interview he provides a pointed evaluation of US counterinsurgency (or lack of it) in Afghanistan:

I think the big lesson of Afghanistan is that we can’t afford to do this. COIN may be a great theory, but it probably will be irrelevant for the United States for the foreseeable future because it’s just too damned expensive and time consuming. You have to understand the value of the object you are trying to save with counterinsurgency—essentially your classic cost-benefit analysis. Even starting in 2009, if we’d mounted a real full-on COIN effort, we probably could have gotten to a better point today. We shouldn’t kid ourselves that what we did was full-on COIN—that would have involved more troops, more money, more civilian experts. But would all of that have been worth it? Was what we’ve already spent on this effort worth it? Particularly given the other national security challenges we face? The economic stagnation at home? So, the debate over COIN I think misses a key point: it’s not whether it works or not. It’s whether it’s a worthwhile expenditure or not.

(Little America reports that the cost of keeping one US service member in Afghanistan for a year is $1 million… though there are, of course, many other non-monetary costs that fall on many other people).

Chandrasekaran offers a more detailed and nuanced discussion of counterinsurgency in Afghanistan in a fine interview with Peter Munson at the Small Wars Journal.

I described Chandrasekaran as a journalist but he’s (even) more: his website records his residencies as a public policy scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center and the Center for a New American Security – which is where he converted his ‘sand-encrusted notebooks’ into the manuscript of Little America – and the International Reporting Project at the Johns Hopkins School for Advanced International Studies.

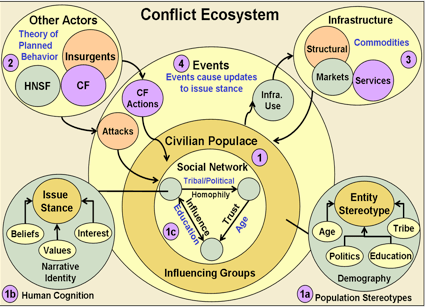

I’m making so much of Chandresekaran’s emphasis on the conduct of counterinsurgency and the connections between reporting and reflection because the academic critique of contemporary counterinsurgency has drawn a bead on the doctrine so vigorously advertised by the US Army and Marine Corps in 2006. When I wrote “Rush to the intimate” (DOWNLOADS tab) the new field manual FM 3-24 had just been released, and I was interested in how this – together with changes in pre-deployment training, technology and the rest – described a ‘cultural turn’ of sorts that seemed to be addressed as much to the American public as it was to the American military. (In later work I’ve explored the bio-political dimensions of counterinsurgency too, and I’m presently revising those discussions for the book).

I’m making so much of Chandresekaran’s emphasis on the conduct of counterinsurgency and the connections between reporting and reflection because the academic critique of contemporary counterinsurgency has drawn a bead on the doctrine so vigorously advertised by the US Army and Marine Corps in 2006. When I wrote “Rush to the intimate” (DOWNLOADS tab) the new field manual FM 3-24 had just been released, and I was interested in how this – together with changes in pre-deployment training, technology and the rest – described a ‘cultural turn’ of sorts that seemed to be addressed as much to the American public as it was to the American military. (In later work I’ve explored the bio-political dimensions of counterinsurgency too, and I’m presently revising those discussions for the book).

Since then there has been a stream of detailed examinations of the doctrine and its genealogy, and I’d particularly recommend:

Ben Anderson, ‘Population and affective perception: biopolitics and antiicpatory action in US counterinsurgency doctrine’, Antipode 43 (2) (2011) 205-36

Josef Teboho Ansorge, ‘Spirits of war: a field manual’, International political sociology 4 (2010) 362-79

Alan Cromartie, ‘Field Manual 3-24 and the heritage of counterinsurgency theory’, Millennium 41 (2012) 91-111

Marcus Kienscherf, ‘A programme of global pacification: US counterinsurgency doctrine and the biopolitics of human (in)security’, Security dialogue 42 (6) (2012) 517-35

Patricia Owens, ‘From Bismarck to Petraeus:the question of the social and the social question in counterinsurgency’, European journal of international relations [online early: March 2012]

There is indeed something odd about a mode of military operations that advertises itself as ‘the graduate level of war’ (one of Petraeus’s favourite conceits about counterinsurgency) and yet describes a ‘cultural turn’ that is decades behind the cultural turns within the contemporary humanities and the social sciences. There’s also been a vigorous debate about the enlistment of the social sciences, particularly anthropology, in the doctrinal ‘weaponizing’ of culture – though I sometimes worry that this contracts to a critique of weaponizing anthropology. (I don’t mean the latter is unimportant – as David Price‘s important work demonstrates – and there are obvious connections between the two. But disciplinary purity is the least of our problems).

That said, the discussion of counterinsurgency surely can’t be limited to a single text, its predecessors and its intellectual credentials. If there has been a ‘cultural turn’, then its codification now extends far beyond FM 3-24 (which is in any case being revised); if the domestic audience was an important consideration in 2006, the public has certainly lost interest since then (and, if the US election is any guide, in anything other than an air strike on Iran); and whatever the attractions of large-scale counterinsurgency operations in the recent past, Obama’s clear preference is for a mix of drone strikes, short-term and small-scale Special Forces operations, and cyberwar.

But – Chandresekaran’s sharp point (and Clausewitz’s too) – there’s also a difference between ‘paper war’ and ‘real war’. Here are just two passages from former Lieutenant Matt Gallagher‘s Kaboom: embracing the suck in a savage little war (Da Capo, 2010) that dramatise the difference between the Field Manual and the field:

‘There was a brief pause and then [Staff Sergeant Boondock] continued. “Think I’ll be able to bust Cultural Awareness out on one of the hajjis now?” he said, referring to the stun gun he carried on his ammo pack… we were all waiting for the day that some Iraqi did something to warrant its electric kiss’ (p. xi).

‘There was a brief pause and then [Staff Sergeant Boondock] continued. “Think I’ll be able to bust Cultural Awareness out on one of the hajjis now?” he said, referring to the stun gun he carried on his ammo pack… we were all waiting for the day that some Iraqi did something to warrant its electric kiss’ (p. xi).

‘In this malleable, flexible world, creativity and ingenuity replaced firepower and overwhelming force as the central pillars of the army’s output. Ideally, a decentralized army struck like a swarm of killer bees rather than a lumbering elephant… In conventional warfare, the order of war dissolved into anarchy as time yielded more and more blood. Unconventional, decentralized warfare was the exact opposite. In fluid theory and historical practice, victorious counterinsurgencies served as a shining inverse to … conventionality, because through anarchy and bloodshed, order could eventually be established. This was the war I had trained for, brooded over, and studied. Then there was the war I fought’ (p. 175)

There’s also a particularly telling passage in David Finkel‘s The good soldiers (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2009) that speaks directly to COIN spinning, to its address to the American public and, more particularly, to the body politic:

‘Soldiers such as Kauzlarich might be able to talk about the war as it was playing out in Iraq, but after crossing the Atlantic Ocean from one version of the war to the other, Petraeus had gone to Washington to talk about the war as it was playing out in Washington‘ (p. 130),

I’ve been gathering lots more examples from accounts like these – some of which, like Gallagher’s, started out as military blogs – but one of Chandresekaran’s many achievements is to show what can (must) be achieved when we to turn to an examination of practice.

There have been other studies of counterinsurgency operations – some from within the military, some from within the academy, and some at the nexus between the two – but the need to explore the connections between theory and practice (which are always two-way: the military constantly seeks to incorporate what it calls ‘lessons learned’ into its training) has never been greater.

This isn’t limited to counterinsurgency either: it’s one thing to demand to know what the ‘rules’ governing drone strikes are, for example, but quite another to monitor their implementation.

For academics, none of this is straightforward. We aren’t war correspondents – and my own debt to courageous journalists like Chandresekaran is immense – and I suspect most of us would be unwilling to enlist in Human Terrain Teams. There’s a long history to geography‘s military service; today some geographers undertake (critical) field work in war zones – Jennifer Fluri, Philippe le Billon, Michael Watts and others – and no doubt many more geographers live in them.

There’s also a particularly rich anthropology written from war zones. I’m thinking in particular of the work of Sverker Finnström (Living with bad surroundings, Duke, 2008), Danny Hoffman (The war machines, Duke, 2011), and Carolyn Nordstrom (especially A different kind of war story, SBS, 2002 and Shadows of war, University of California Press, 2004).

There’s also a particularly rich anthropology written from war zones. I’m thinking in particular of the work of Sverker Finnström (Living with bad surroundings, Duke, 2008), Danny Hoffman (The war machines, Duke, 2011), and Carolyn Nordstrom (especially A different kind of war story, SBS, 2002 and Shadows of war, University of California Press, 2004).

All of these studies approach ‘fieldwork under fire’ from a radically different position to David Kilcullen‘s ‘conflict ethnography’ (which is placed directly at the service of counterinsurgency operations) but, as Neil Whitehead showed, they still raise serious ethical questions about witnessing violence and, indeed, the violence of what he called ‘ethnographic interrogation’ that is often aggravated in a war zone. (For more, see Fieldwork under fire (left) and Sascha Helbardt, Dagmar Hellmann-Rajanayagam and Rüdiger Korff, ‘War’s dark glamour’, Cambridge Review of International Affairs 23 (2) (2010) 349-69).

To be sure, there is important work to be done ‘off stage’ and in the vicinity of war, as Wendy Jones insists in ‘Lives and deaths of the imagination in war’s shadow’, Social anthropology 19 (2011) 332-41, and overtly techno-cultural modes of remote witnessing have their own dilemmas. But the dangers involved in venturing beyond our screens – and outside our emerald cities – are more than corporeal: they are also intellectual and ethical.

Chandresekaran’s principled combination of reporting and reflection shows how necessary it is to face them down.

In posting this, I’m mindful not only of Rob Sullivan‘s critical response to Trevor Paglen‘s The Last Pictures (incidentally, the URL gloriously converts Paglen to “Pagen”….) and all those interested in ‘zombie geographies‘… For a different take that none the less loops back to Der Derian’s concerns in both his films, see Gaston Gordillo‘s perceptive commentary on Marc Forster’s forthcoming film World Revolution Z, based on Max Brooks‘s novel:

In posting this, I’m mindful not only of Rob Sullivan‘s critical response to Trevor Paglen‘s The Last Pictures (incidentally, the URL gloriously converts Paglen to “Pagen”….) and all those interested in ‘zombie geographies‘… For a different take that none the less loops back to Der Derian’s concerns in both his films, see Gaston Gordillo‘s perceptive commentary on Marc Forster’s forthcoming film World Revolution Z, based on Max Brooks‘s novel: