The debate over the militarisation of policing in the United States that has been sparked by the shooting of a young Afro-American by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri increasingly cites Radley Balko‘s Rise of the warrior cop: the militarisation of America’s police forces. It was published last year to considerable acclaim, and last August the Wall Street Journal‘s Saturday Essay featured what was, in effect, Balko’s three-minute version.

Since the 1960s, in response to a range of perceived threats, law-enforcement agencies across the U.S., at every level of government, have been blurring the line between police officer and soldier. Driven by martial rhetoric and the availability of military-style equipment – from bayonets and M-16 rifles to armored personnel carriers – American police forces have often adopted a mind-set previously reserved for the battlefield. The war on drugs and, more recently, post-9/11 antiterrorism efforts have created a new figure on the U.S. scene: the warrior cop – armed to the teeth, ready to deal harshly with targeted wrongdoers, and a growing threat to familiar American liberties.

So far, so familiar – and by no means confined to the United States. There the present debate seems to have been conducted in an intellectual vacuum. When ‘Warrior cop’ was published, Glenn Greenwald wrote that ‘there is no vital trend in American society more overlooked than the militarization of our domestic police forces’, and he’s since repeated the claim (though he does acknowledge the ACLU report produced earlier this year, War Comes Home: the excessive militarization of American policing (see also Matthew Harwood‘s ‘One Nation Under SWAT’ here – he’s a senior writer/editor at the ACLU).

I suspect the debate could be advanced, both politically and intellectually, by including two other (academic) voices that approach the situation from two different directions. One is Steve Graham‘s Cities under siege: the new military urbanism (2010), which starts from new constellations of military violence, and the other is Mark Neocleous‘s War power, police power (2014), which starts from a wider conception of policing than has figured in the present discussion. Doing so would also enable the role of racialisation – which flickers in the margins of both accounts – to be given the greater prominence I think it deserves. But it would also considerably sharpen talk of war ‘coming home’, as though it ever left…

For now, though, let me make two further points. One is about the need to enlarge the conventional conception of the military-industrial complex. It has already been extended in all sorts of ways, of course – the Military-Industy-Media-Entertainment complex (MIME) and the Military-Academic-Industrial-Media complex (MAIM) to name just two – but it has become increasingly clear that the producers and designers of military equipment also have domestic police forces in their sights (sic).

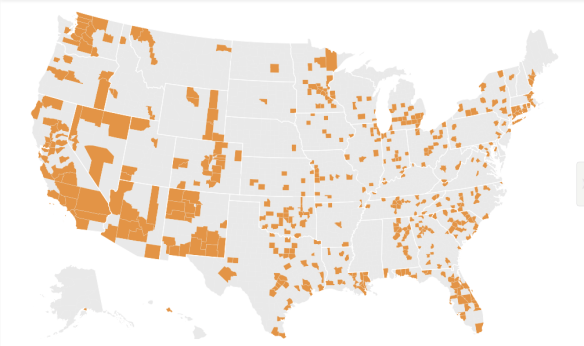

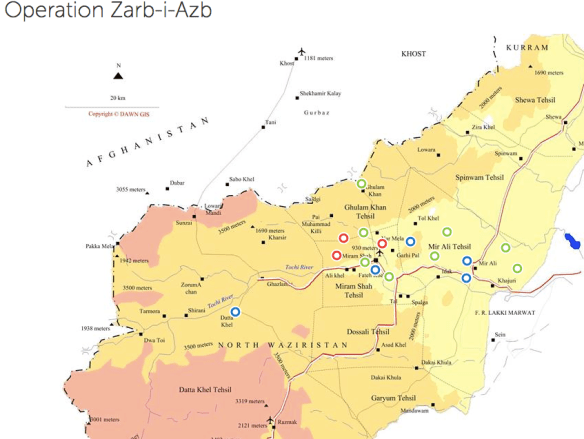

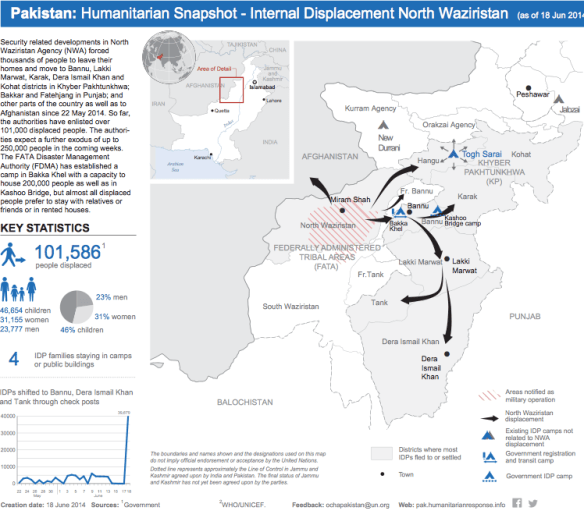

It’s a complicated business, because on one side there is an active Department of Defense program that, since 1990, has channelled surplus military equipment to state and local police departments in the United States: more details from Shirley Li here. The New York Times has a sequence of interactive maps showing the spread of everything from aircraft and armoured vehicles through grenade launchers and assault rifles to body armour and night vision goggles (the accompanying article is here). The map below is just one example, showing the transfer of armoured vehicles:

On the other side, there’s also an active market for new equipment – and some of the latest ‘toys for the boys‘ (see also here) include drones (at present unarmed versions only for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance). Jane’s, widely acknowledged as an indispensable global database on military equipment and platforms, now advertises a new guide dedicated to ‘Police and Homeland Security Equipment’:

Jane’s Police & Homeland Security Equipment delivers a comprehensive view of law enforcement and paramilitary equipment in production and service around the world, providing A&D businesses with the market intelligence that drives successful business development, strategy and product development activity, and providing military, security and government organizations with the critical technical intelligence that they need in order to develop and maintain an effective capability advantage….

Profiles of more than 2,200 types of law enforcement equipment and services around the world, including firearms, body armor, personal protection, riot and crowd control equipment, communications, security equipment and biometric solutions, make Jane’s Police & Homeland Security Equipment the most comprehensive and reliable source of police equipment technical and program intelligence.

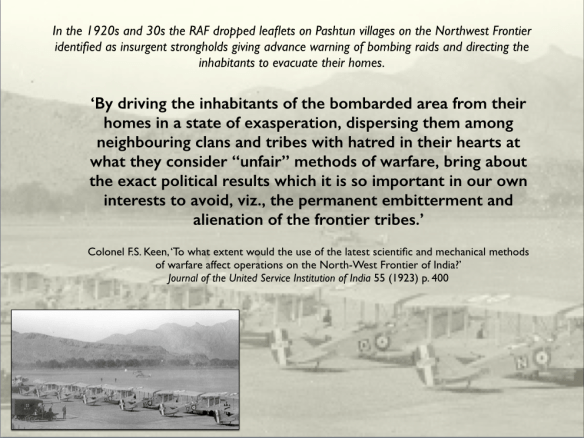

There is a genealogy to all of this, of course, which means there is important work to be done in tracing the historical pathways through which both offensive and defensive materials have migrated from external uses (by the military) to internal uses (by the police). This breaches one of the canonical divides of the liberal state, a rupture signalled by the hybrid term ‘security forces’, but it has been going on for a long time.

In an excellent essay – a preview of her book, Tear Gas: 100 years in the making, due out from Verso next year – Anna Feigenbaum shows how tear gas drifted from the battlefields of France and Belgium onto streets around the world. The French were the first to use toxic gas shells on a large scale – engins suffocants – which discharged tear gas; in most cases the effects were irritating rather than disabling, and when the Germans used similar shells against the British in October 1914 at Neuve Chapelle they too proved largely ineffective.

In an excellent essay – a preview of her book, Tear Gas: 100 years in the making, due out from Verso next year – Anna Feigenbaum shows how tear gas drifted from the battlefields of France and Belgium onto streets around the world. The French were the first to use toxic gas shells on a large scale – engins suffocants – which discharged tear gas; in most cases the effects were irritating rather than disabling, and when the Germans used similar shells against the British in October 1914 at Neuve Chapelle they too proved largely ineffective.

These were ‘Lilliputian efforts’, according to historian Peter Bull, and experiments by both sides with other systems were aimed at a greater and deadlier harvest. You can find much more on the use of lethal gas on the battlefield from Ulrich Trumpener, ‘The road to Ypres’, Journal of modern history 47 (1975) 460-80; Tim Cook, No place to run: the Canadian Corps and gas warfare in the First World War (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1999) – which despite its title is much less Canuck-centric than it might appear; Jonathan Krause, ‘The origins of chemical warfare in the French Army’, War in history 20 (4) (2013) 545-56; and Edgar Jones, ‘Terror weapons: the British experience of gas and its treatment in the First World War’, War in history 21 (3) (2014) 355-75.

But many military officers realised that tear gas had other potential uses, and Anna shows that the process of repatriation and re-purposing began even before the First World War had ended:

By the end of the 1920s, police departments in New York, Philadelphia, Cleveland, San Francisco, and Chicago were all purchasing tear-gas supplies. Meanwhile, sales abroad included colonial territories in India, Panama, and Hawaii.

With this new demand for tear gas came new supply. Improved tear-gas cartridges replaced early explosive models that would often harm the police deploying them….

Leading American tear-gas manufacturers, including the Lake Erie Chemical Company founded by World War I veteran Lieutenant Colonel Byron “Biff” Goss, became deeply embroiled in the repression of political struggles. Sales representatives buddied up with business owners and local police forces. They followed news headlines of labor disputes and traveled to high-conflict areas, selling their products domestically and to countries such as Argentina, Bolivia, and Cuba. A Senate subcommittee investigation into industrial-munitions sales found that between 1933 and 1937, more than $1.25 million (about $21 million today) worth of “tear and sickening gas” had been purchased in the U.S. “chiefly during or in anticipation of strikes.”

Anna continues the story through the Second World War and the Vietnam War (where in an unremarked irony tear gas was used against anti-war demonstrations) and down to the present, but you get the (horrible) idea. She closes with the supreme irony:

Yet while tear gas remains banned from warfare under the Chemical Weapons Convention, its use in civilian policing grows. Tear gas remains as effective today at demoralizing and dispersing crowds as it was a century ago, turning the street from a place of protest into toxic chaos. It clogs the air, the one communication channel that even the most powerless can use to voice their grievances.

This brings me to my second point, and it’s one that both Steve and Mark sharpen in different ways: the militarization of policing is not only about weapons but also about the the practices in which they are embedded. One place to start such an investigation would be the cross-over in what the military calls doctrine. There’s many a slip between doctrine on the books and practice on the streets. But Public Intelligence has recently published U.S. Army Techniques Publication 3-39.33: Civil Disturbances, which will now repay even closer reading. The cross-overs between counterinsurgency, counter-terrorism and police operations against organised crime are now a matter of record – and I’ve discussed these on several occasions (see here and here) – but 3-39.33 is perhaps most revealing in its preamble:

ATP 3-39.33 provides discussion and techniques about civil disturbances and crowd control operations that occur in the continental United States (CONUS) and outside the continental United States (OCONUS)….Worldwide instability coupled with U.S. military participation in unified-action, peacekeeping, and related operations require that U.S. forces have access to the most current doctrine and techniques that are necessary to quell riots and restore public order.

Which is where I came in… These are just preliminary jottings, and there’s lots more to say – and lots more to consider (as the Martha Rosler photomontage at the top of this post implies: it’s from her 2004 series Bringing the War Home: House Beautiful, which carries an implicit plea to attend to their homes and their streets not just ‘ours’ ) – so watch this space.

UPDATE: See Stuart Schrader‘s elegant short essay on ‘Policing Empire’ at Jacobin:

‘… we should be skeptical of calls for police reform, particularly when accompanied by cries that this (militarization) should not happen here. A close look at the history of US policing reveals that the line between foreign and domestic has long been blurry. Shipping home tactics and technologies from overseas theaters of imperial engagement has been a typical mode of police reform in the United States. When policing on American streets comes into crisis, law-enforcement leaders look overseas for answers. What transpired in Ferguson is itself a manifestation of reform.

From the Philippines to Guatemala to Afghanistan, the history of US empire is the history of policing experts teaching indigenous cops how to patrol and investigate like Americans. As a journalist observed in the late 1950s, “Americans in Viet-Nam very sincerely believe that in transplanting their institutions, they will immunize South Viet-Nam against Communist propaganda.” But the flow is not one-way: these institutions also return home transformed.’

Thanks to Alex Vasudevan for the tip.