Rummaging around for more people working on militarized vision, I encountered a forum on Military optics and Bodies of difference held at Berkeley’s Center for Race and Gender earlier this year, and through that the research of Katherine Chandler, who holds a Townsend Center for the Humanities Dissertation Fellowship in the Department of Rhetoric. Her dissertation in progress is entitled Drone Flight and Failure: the United States’ Secret Trials, Experiments and Operations in Unmanning, 1936 – 1973, which promises to fill in a crucial gap in conventional genealogies of today’s remote operations.

As you’ll see if you visit her website here, Katherine is an accomplished artist as well as researcher and critic. You can read her essay on ‘System Failures’, which includes a discussion of Trevor Paglen‘s Drone Vision and Omer Fast‘s 5,000 Feet is the Best, at The New Inquiry (August 2012) here, and find a fuller discussion of Fast’s video situated within what Katherine calls the ‘knowledge politics’ and political ecologies of remote operations on pp. 63-74 of Knowledge politics and intercultural dynamics here.

Here is the abstract for her talk at the forum, Unmanning Politics: Aerial Surveillance 1960-1973:

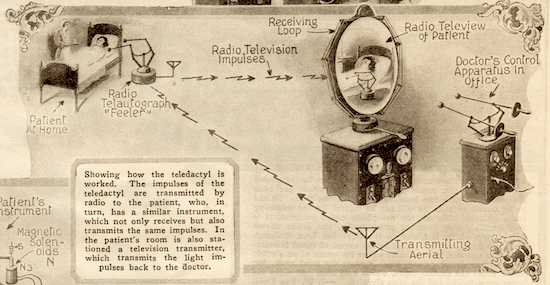

On May 1, 1960, Francis Gary Powers’ U-2 plane was shot down over the Soviet Union while on a secret reconnaissance mission. The ensuing diplomatic fallout caused the cancellation of the Paris Summit between Dwight Eisenhower and Nikita Khrushchev. Less well known, in April 1960, Robert Schwanhausser, an engineer for Ryan Aeronautical, briefed the United States Air Force on the possibility that its Firebee target drone, used at the time for air defense training, might be re-engineered as an unmanned reconnaissance plane. In the weeks following the Powers incident, the Air Force began wholesale negotiations with Ryan Aeronautical to develop a pilotless spy plane and, on July 8, 1960, the company was given funding to begin the project. Among the noted advantages were: “political risk is minimized due to the absence of a possible prisoner” (“Alternative Reconnaissance System,” 1960). I investigate the resulting Lightning Bugs, flown for three-thousand reconnaissance missions in Southeast Asia between 1964 and 1973.

On May 1, 1960, Francis Gary Powers’ U-2 plane was shot down over the Soviet Union while on a secret reconnaissance mission. The ensuing diplomatic fallout caused the cancellation of the Paris Summit between Dwight Eisenhower and Nikita Khrushchev. Less well known, in April 1960, Robert Schwanhausser, an engineer for Ryan Aeronautical, briefed the United States Air Force on the possibility that its Firebee target drone, used at the time for air defense training, might be re-engineered as an unmanned reconnaissance plane. In the weeks following the Powers incident, the Air Force began wholesale negotiations with Ryan Aeronautical to develop a pilotless spy plane and, on July 8, 1960, the company was given funding to begin the project. Among the noted advantages were: “political risk is minimized due to the absence of a possible prisoner” (“Alternative Reconnaissance System,” 1960). I investigate the resulting Lightning Bugs, flown for three-thousand reconnaissance missions in Southeast Asia between 1964 and 1973.

Researching how aircraft were unmanned during the Cold War is instructive both in the ways they mimic contemporary unmanned combat aerial vehicles and trouble assumptions about them. I follow how unmanned systems operated within the logics of American Cold War politics and their perceived usefulness geopolitically – crossing borders as spy aircraft, collecting and jamming electronic signals, and gathering battlefield reconnaissance. I ask how conquest, and the ensuing assumptions of empire, colonialism and race, underlie the unmanning of military aircraft, even while these aspects were purposefully, although, unsuccessfully occluded through the idea that technologies could mitigate political risks. Moreover, unmanned reconnaissance projects were cancelled at the end of the Vietnam War and their failure provides clues about what might be left out of visions of aerial control and the ways politics, and human vulnerabilities, persisted in spite of efforts to engineer systems that would suggest otherwise.

The legitimacy of contemporary drone strikes relies on the ability of unmanned aircraft to “see” enemy targets. Yet, as Isabel Stengers has argued, any representation gives value. Looking at the few available images from these early unmanned reconnaissance flights, I move between what is seen and unseen to examine how values, particularly, secrecy and control, are formed through unmanned reconnaissance. Claiming to produce a mechanical, rather than political, view of the territories surveyed, I show how the supposedly apolitical lens of the drone occludes how politics, industry and military come together to privilege certain positions and target others.

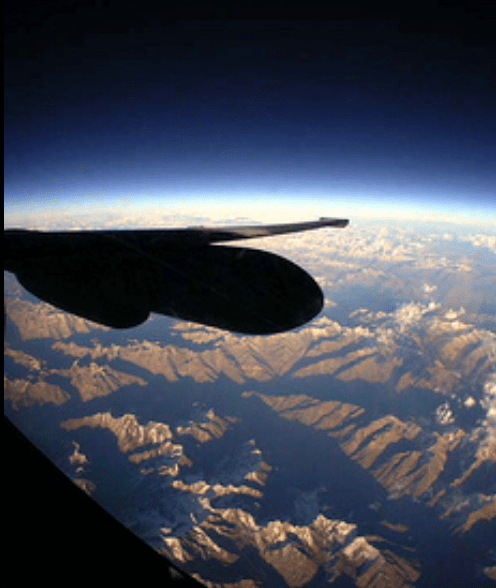

Interesting stuff – especially that first paragraph linking ‘un-manning’ to the U-2. There is a strange irony here, because until this year the US Air Force had in fact favoured its fleet of 33 U-2 (‘Dragon Lady’) aircraft [one of which is shown at the top of the photograph] over the high-altitude Global Hawk [shown at the bottom], so much so that it had asked for permission to cancel its orders for the new Block 30 Global Hawks and place others in storage.

You may be surprised to discover that the U-2 is still flying, but the airframe has been repeatedly modified and so too has the network in which it is embedded. One pilot explained:

“The U-2 started out only carrying a wet-film camera. Now, with today’s technology, I’m alone up there, but I may be carrying 40 to 50 Airmen via data link who are back at a (deployable ground station).”

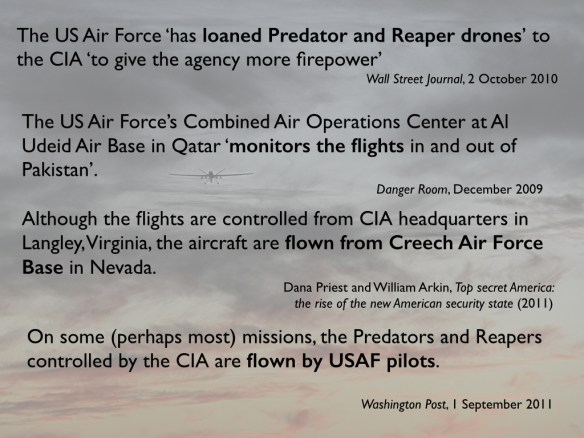

It’s important to remember that Predators and Reapers are not the only platforms streaming imagery to the Air Force’s Distributed Common Ground System. The U-2 was given a new lease of life by the Gulf War in 1991, when nine U-2s flying out of the UAE provided 50 per cent of all imagery and over 90 per cent of all ground forces targeting imagery. During the invasion of Iraq in 2003 U-2s flew only 19 percent of the air reconnaissance missions, but they provided more than 60 per cent of the signals intelligence and 88 per cent of battlefield imagery. The continuing wars in Afghanistan and Iraq confirmed that the U-2’s original, strategic significance had been eclipsed by its new tactical role. Chris Pocock explains:

It’s important to remember that Predators and Reapers are not the only platforms streaming imagery to the Air Force’s Distributed Common Ground System. The U-2 was given a new lease of life by the Gulf War in 1991, when nine U-2s flying out of the UAE provided 50 per cent of all imagery and over 90 per cent of all ground forces targeting imagery. During the invasion of Iraq in 2003 U-2s flew only 19 percent of the air reconnaissance missions, but they provided more than 60 per cent of the signals intelligence and 88 per cent of battlefield imagery. The continuing wars in Afghanistan and Iraq confirmed that the U-2’s original, strategic significance had been eclipsed by its new tactical role. Chris Pocock explains:

“The U-2 today is more a tactical intelligence gatherer… It supports ground operations on a daily basis, flying over Afghanistan, flying around Korea, flying in the eastern Mediterranean, doing all those things every day and it’s actually not only providing intelligence that is analyzed for the benefit of those ground troops, but it’s actually in contact with those ground troops in real time.”

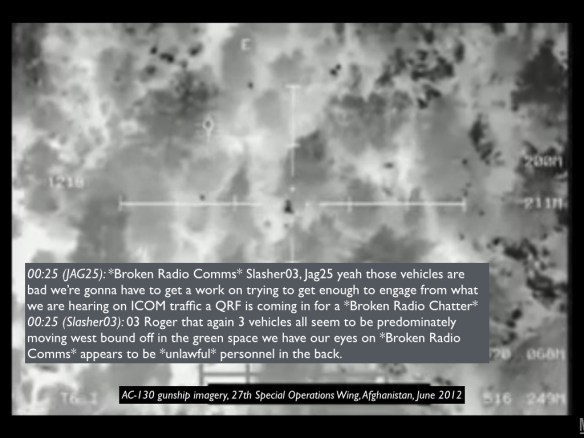

And that close contact – akin to the intimacy remote operators in the continental United States claim when they say they are not 7,000 miles but 18 inches from the battlespace, the distance from eye to screen – takes its toll on the U-2 pilots too. In addition to the extraordinary pressures flying the U-2 imposes on their bodies, one USAF physician insisted that ’emotionally… they’re wrung out from that… When you’re talking to somebody on the radio and there’s gunfire in the background… you’re not taking a nap while that’s happening.’

Writing in the New York Times, Christopher Drew provided a revealing example:

Major Shontz said he was on the radio late last year with an officer as a rocket-propelled grenade exploded. “You could hear his voice talking faster and faster, and he’s telling me that he needs air support,” Major Shontz recalled. He said that a minute after he relayed the message, an A-10 gunship was sent to help.

In fact, that last clause can be generalised; the U-2 has often been deployed in close concert with other platforms, including Predators and Reapers. Drew again:

The U-2’s altitude [70,000 feet or more], once a defense against antiaircraft missiles, enables it to scoop up signals from insurgent phone conversations that mountains would otherwise block. As a result, Colonel Brown said, the U-2 is often able to collect information that suggests where to send the Predator and Reaper drones, which take video and also fire missiles. He said the most reliable intelligence comes when the U-2s and the drones are all concentrated over the same area, as is increasingly the case.

Part of the reason for that is that the U-2 has such an advanced imagery system:

Even from 13 miles up its sensors can detect small disturbances in the dirt, providing a new way to find makeshift mines [IEDs] that kill many soldiers. In the weeks leading up to the [2010] offensive in Marja, military officials said, several of the … U-2s found nearly 150 possible mines in roads and helicopter landing areas, enabling the Marines to blow them up before approaching the town.

Marine officers say they relied on photographs from the U-2’s old film cameras, which take panoramic images at such a high resolution they can see insurgent footpaths, while the U-2’s newer digital cameras beamed back frequent updates on 25 spots where the Marines thought they could be vulnerable.

For all that, in the last two years the Air Force’s plan to cut the Global Hawk program was repeatedly over-ridden by Congress, in response to an extraordinary campaign waged by Northrop Grumman, which launched what Mark Thompson called ‘its own ISR – intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance – mission over Capitol Hill to decide where to strategically target cash-bombs to keep its plane, and more of them, flying for another day’: you can find a full report at the Center for Public Integrity here.

The Air Force has now accepted the retirement of Lockheed Martin’s ageing Cold warrior, because (so it says) the cost per flying hour of the Hawk has now fallen below that of the U-2 ($24,000 vs. $32,000). ‘U2 shot down by budget cuts’, is how PBS put it, while the Robotics Business Review triumphantly announced ‘Here comes automated warfare’.

Even so, cost per flying hour is not the whole story, as Amy Butler explains. Part of the problem is logistical and, by extension, geopolitical: ‘Global Hawks based in Guam have to transit for hours just to reach North Korea, whereas the U-2, based at Osan air base, South Korea, has a shorter commute’ (details of the Hawk’s global basing can be found here).

A second issue is reliability, which bedevils all major UAVs and makes cost per flying hour a dubious index:

‘Intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance collection is in high demand, and aircraft downtime is extremely worrisome for combatant commanders. In the Pacific, 55% of Global Hawk’s missions were canceled in fiscal 2013; 96% of the U-2’s missions were achieved. The U-2 was also scheduled for nearly three times as many missions. Global Hawk lacks anti-icing equipment and is not able to operate in severe weather.’

Finally, critics continue to complain that the sensors on the U-2 remain superior to those on the Hawk and provide a wider field of view. According to a report from Eric Beidel,

The Global Hawk carries Raytheon’s Enhanced Integrated Sensor Suite, which includes cloud-penetrating radar, a high-resolution electro-optical digital camera and an infrared sensor. But the U-2’s radar can see farther partly because the plane can fly at altitudes over 70,000 feet, about 10,000 feet higher than a Global Hawk. A longer focal length also gives the U-2’s camera an edge, experts said…

Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Norton Schwartz has said that the drone’s sensors just weren’t cutting it. Further, the U-2 can carry a larger payload, up to 5,000 pounds compared to 3,000 pounds for the Global Hawk.

“Some of the most useful sensors are simply too big for Global Hawk,” said Dave Rockwell, senior electronics analyst at Teal Group Corp. He referred to an optical bar camera on the U-2 that uses wet film similar to an old-fashioned Kodak. “It’s too big to fit on Global Hawk even as a single sensor.”

All of these technical considerations are also political ones, as Katherine’s abstract indicates, and none of them answers the other questions she poses about what can and cannot be seen…