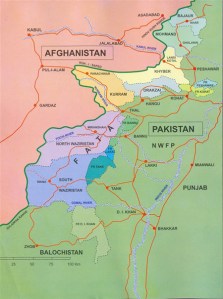

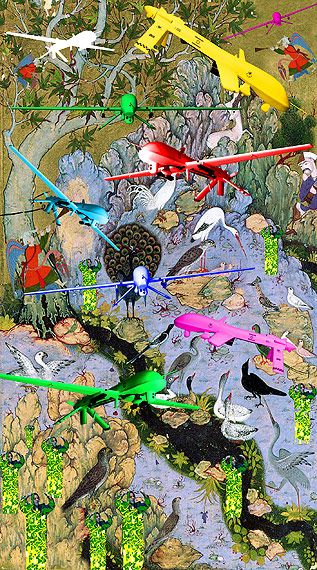

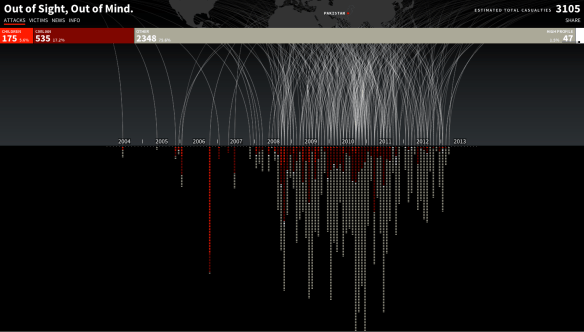

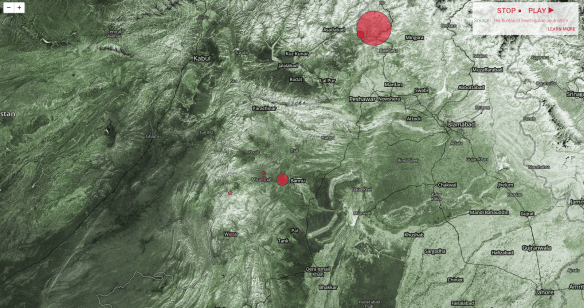

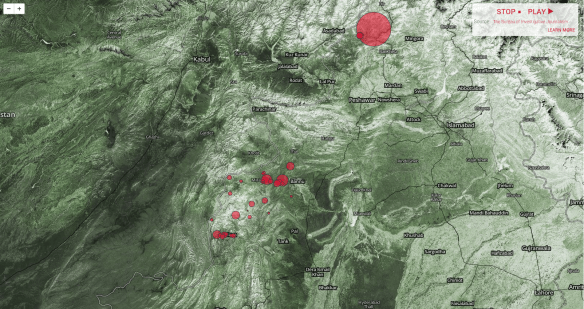

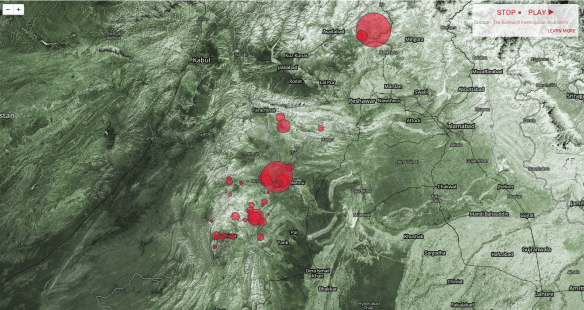

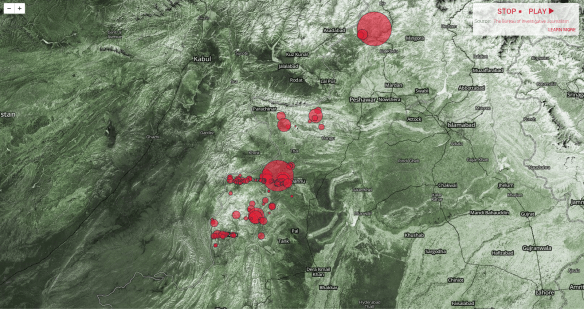

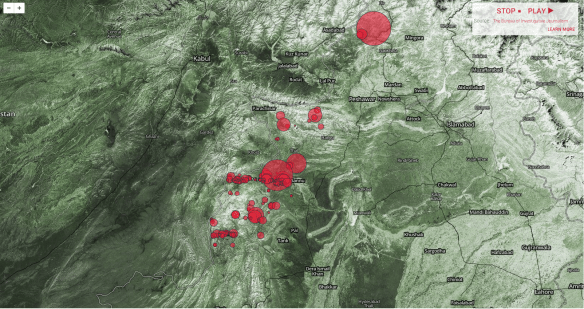

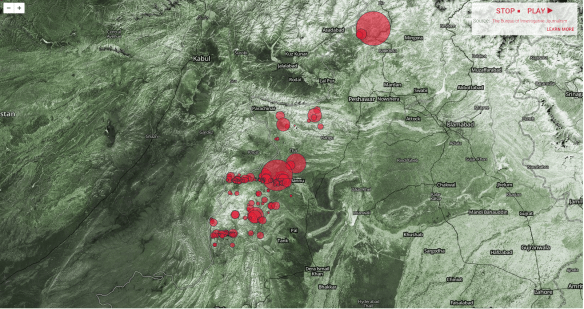

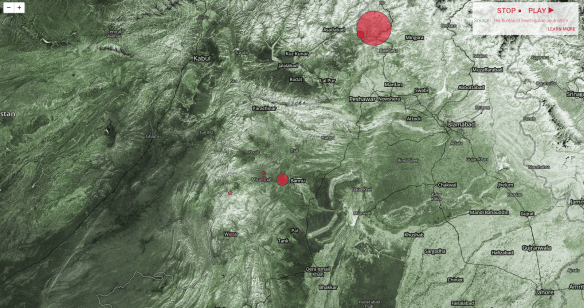

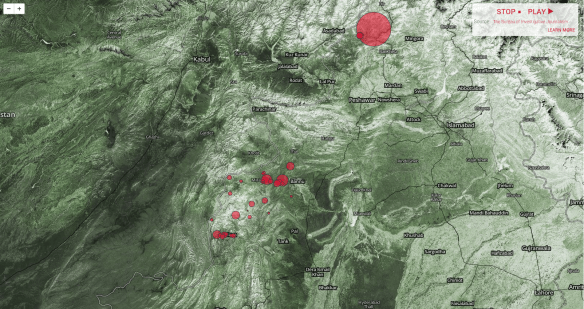

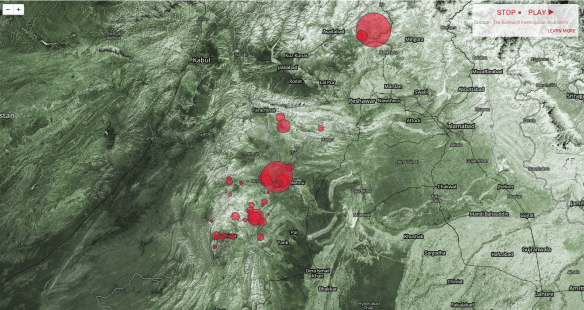

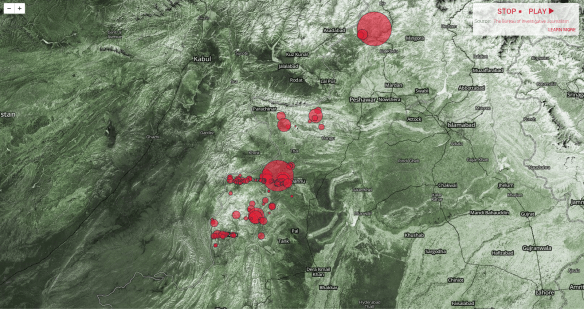

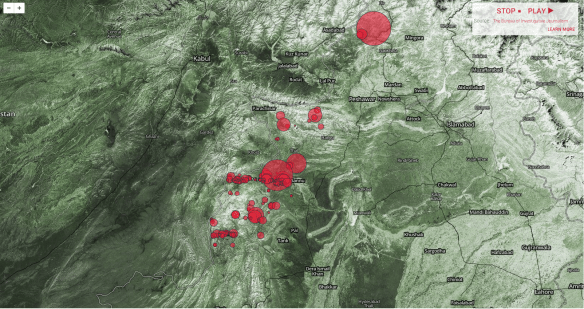

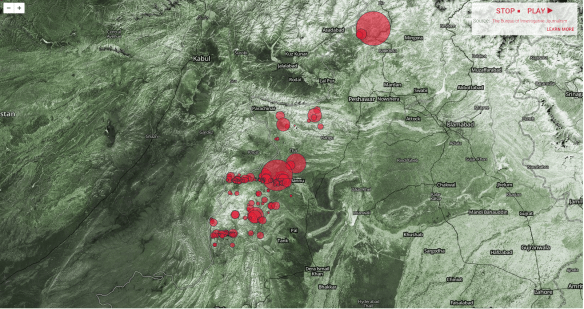

Following up my post on the air campaigns waged by the United States and by Pakistan inside the Federally Administered Tribal Territories and the North-West Frontier Province (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), here are some screenshots from Chris Herwig‘s remarkable cartographic animation of casualties from US drone strikes from 2004 through to the present (data from the Bureau of Investigative Journalism):

Casualties from US drone strikes to end December 2007

Casualties from US drone strikes to end December 2008

Casualties from US drone strikes to end December 2009

Casualties from US drone strikes to end December 2010

Casualties from US drone strikes to end December 2011

Casualties from US drone strikes to end December 2012

You can see the rapid escalation of strikes in 2009-2010 and their contraction in 2011-2012. There is also a tendency for later strikes to cause fewer casualties; the Bureau suggests that this may have been the result of a deliberate decision to limit civilian casualties (the CIA was already reported to be using new, smaller missiles with a restricted blast field and minimal shrapnel by the spring of 2010, so the later change is likely to be down to a mix of better intelligence and greater circumspection) and, more recently, of a switch away from ‘signature strikes’ – the two are of course related – and John Brennan, who was one of the main boosters of the programme’s expansion, now claims that drone strikes are a weapon ‘of last resort’. Maybe; most sources agree that even as the numbers of deaths dwindled, so too did their tactical significance. By February 2011 it was clear that fewer and fewer were so-called ‘high-value targets’ and more and more were simply foot-soldiers.

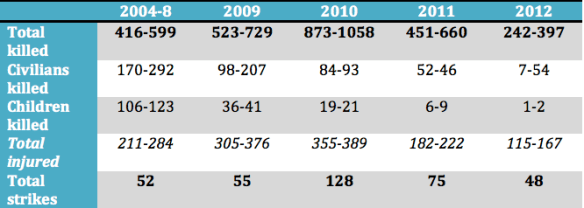

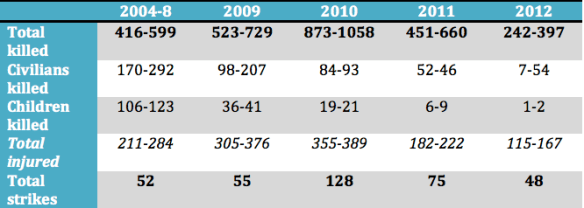

Here are the Bureau’s raw figures:

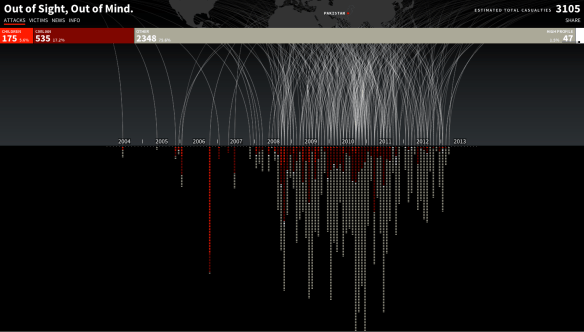

You can find an interactive animation of the Bureau’s tabulations from Pitch Interactive here (thanks to Steve Legg for the tip); the screenshot below doesn’t do justice to the political-aesthetic effect of seeing this in full motion (or of clicking on each strike for the details):

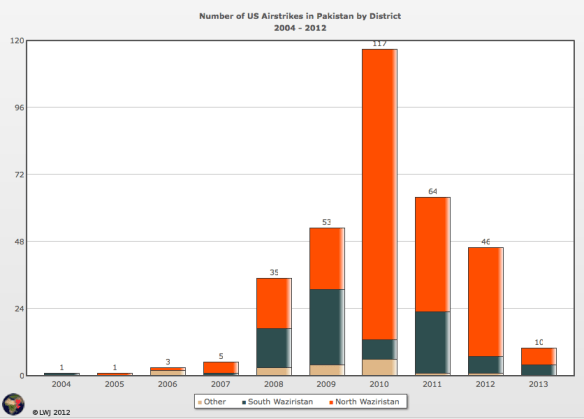

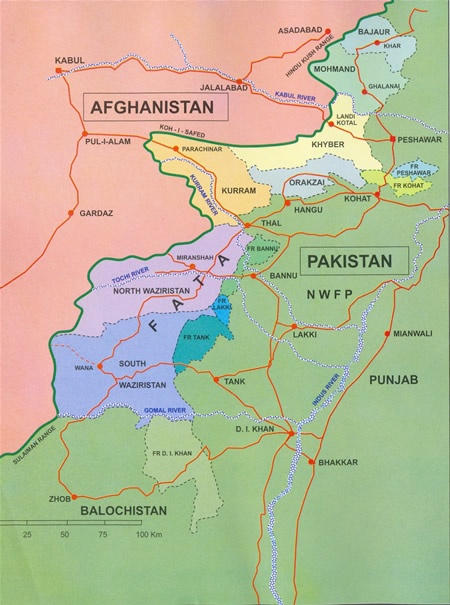

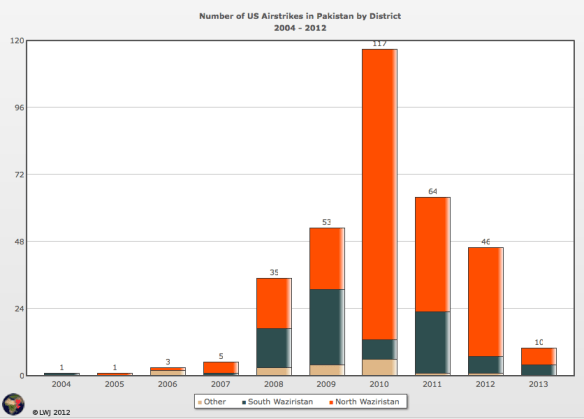

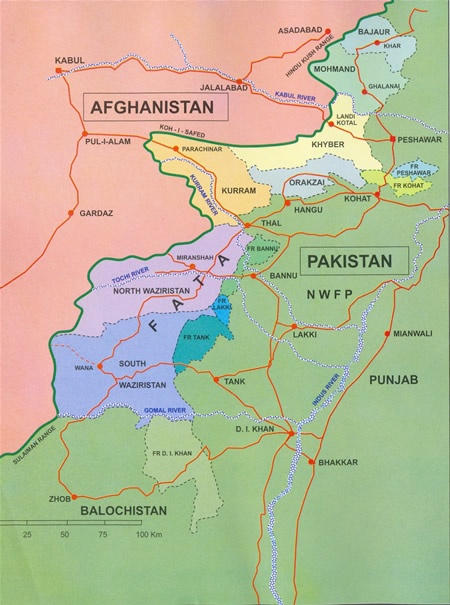

The maps also show that the strikes have been concentrated on North Waziristan, increasingly so since 2010, the locus of the Haqqani Network (which is a longstanding ally of Pakistan’s Inter Services Intelligence), with a secondary concentration on South Waziristan (a key locus of Tehrik-i-Taliban). Here’s a tabulation from the Long War Journal, and although the strike numbers are marginally different from the Bureau’s the geographical concentration is clear:

What the maps can’t convey is the intricate, inconstant gavotte between Pakistan’s various military campaigns and US air strikes in the borderlands since 2004. In the wake of 9/11 and the US-led invasion of Afghanistan, and in response to increasing pressure from Washington, the Pakistan Army launched a number of offensives against militants in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA). In April 2004, after fierce fighting in the mountains of South Waziristan, Islamabad concluded a peace accord with Nek Muhammad, a key militant leader in the agency. But he was killed just two months later, the first casualty of a US drone strike in Pakistan, and the agreement immediately collapsed. In 2005 similar, fragile agreements were negotiated with Baitullah Mehsud, Nek’s successor, and other militant leaders, but these were soon broken. Accords were also signed in North Waziristan in 2006 and 2007 but these too were short-lived. In 2008 a peace accord was signed with the Tehrik-i-Taliban but heavy fighting continued, with major ground and air operations in the agencies to the north of the Khyber Pass. In 2009 Pakistan’s military campaign became even more aggressive. Much of its effort was focused on the northern districts, especially around the Swat Valley, but attention then switched back to South Waziristan. During the summer the Pakistan Air Force carried out regular air strikes in the region; in August 2009 Baitullah Mehsud was killed in a US drone strike. In October 30,000 ground troops entered the region, and US drone strikes in South Waziristan immediately juddered to a (temporary) halt. These operations drove large numbers of militants into Orakzai, which in recent years has been a major target of air strikes by the Pakistan Air Force.

The previous paragraph is little more than a caricature of a highly complex and evolving battlespace, but the gavotte I’ve described has been artfully – if intermittently – choreographed by the US and by Pakistan in fraught concert: so much so that Joshua Foust writes of the ‘Islamabad drone dance’.

This may surprise some readers; earlier this month Ben Emmerson QC, the UN Special Rapporteur on Counterterrorism and Human Rights, concluded a three-day visit to Pakistan by reaffirming what he described as ‘the position of the government of Pakistan’ that drone strikes in the FATA ‘are a violation of Pakistan’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.’ Emmerson met with officials from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Defence and the Secretariat of the FATA – but not, significantly, with anyone from the military or the ISI – who told him that ‘reports of continuing tacit consent by Pakistan to the use of drones on its territory by any other State are false’ and that ‘a thorough search of Government records had revealed no indication of such consent having been given.’ Certainly, the government has repeatedly protested the strikes in public, and the National Assembly passed resolutions in May 2011 and April 2012 condemning them. But Foust insists that Emmerson has been an unwitting participant in the dance.

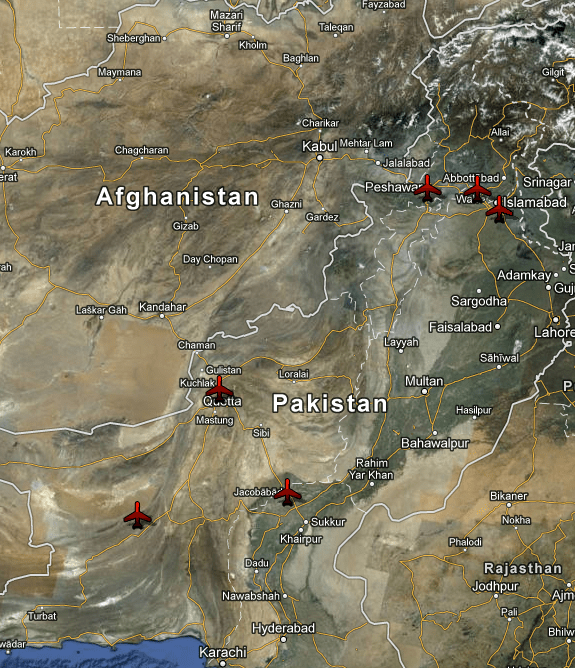

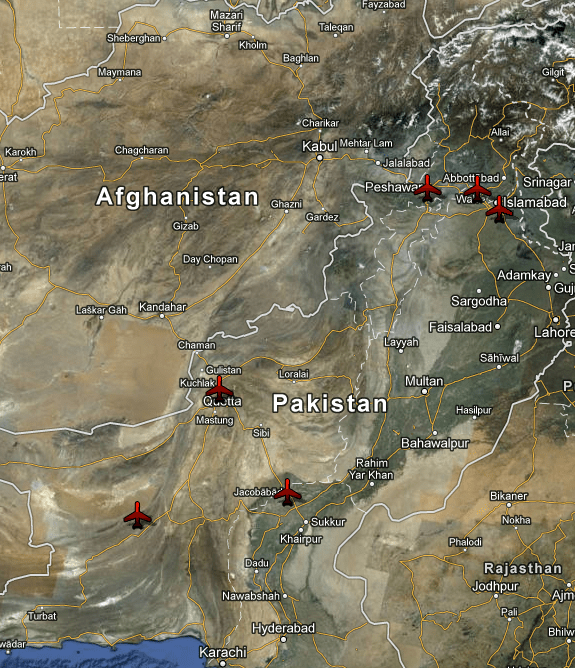

We know, from the Wikileaks cache of diplomatic cables from the US Embassy in Islamabad, that in August 2008 Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gillani told the Ambassador that he approved of the drone strikes as part of ongoing offensives in the FATA – ‘I don’t care if they do it as long as they get the right people’ – and that ‘We’ll protest it in the National Assembly and then ignore it.’ But this was more than ‘tacit consent’. Foust reminds us that, until comparatively recently, US drones were being launched or supported from at least six different air bases inside Pakistan, shown below, including Islamabad, Jacobabad, Peshawar, Quetta and Tarbela Ghazi; the US was ordered to leave Shamsi and had its lease terminated in December 2011.

But there’s more. Pakistan had agreed that the focus of the US strikes would be North and South Waziristan. Earlier that same year, March 2008, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral Mullen asked General Kayani, Pakistan’s Chief of Army Staff, for help in approving ‘a third Restricted Operating Zone for US aircraft over the FATA’, and writing in the Washington Post in November 2010 Greg Miller confirmed that these ‘flight boxes’ were confined to North and South Waziristan (although the US had unsuccessfully pressed for permission to extend the flights over Quetta, outside the FATA). The geometry of those boxes is not known, though it would not be difficult to superimpose two likely rectangles over the previous map sequence. Operational details are, not surprisingly, far from clear. According to a report in the Wall Street Journal on 26 September 2012, the CIA sends a fax to the ISI every month detailing strike zones and intended targets – replies apparently stopped early last year, but the US interprets the silence as ‘tacit consent’ since Pakistan immediately de-conflicts the air space to allow the Predators to carry out their surveillance – and a report in the New York Times earlier this month claimed that the US still provides the Pakistan military with 30 minutes notice of an imminent strike in South Waziristan (but no advance notice for strikes in North Waziristan because the Haqqani Network enjoys such close ties with the ISI that the CIA fears their targets would be warned of the attack).

But there’s more. Pakistan had agreed that the focus of the US strikes would be North and South Waziristan. Earlier that same year, March 2008, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral Mullen asked General Kayani, Pakistan’s Chief of Army Staff, for help in approving ‘a third Restricted Operating Zone for US aircraft over the FATA’, and writing in the Washington Post in November 2010 Greg Miller confirmed that these ‘flight boxes’ were confined to North and South Waziristan (although the US had unsuccessfully pressed for permission to extend the flights over Quetta, outside the FATA). The geometry of those boxes is not known, though it would not be difficult to superimpose two likely rectangles over the previous map sequence. Operational details are, not surprisingly, far from clear. According to a report in the Wall Street Journal on 26 September 2012, the CIA sends a fax to the ISI every month detailing strike zones and intended targets – replies apparently stopped early last year, but the US interprets the silence as ‘tacit consent’ since Pakistan immediately de-conflicts the air space to allow the Predators to carry out their surveillance – and a report in the New York Times earlier this month claimed that the US still provides the Pakistan military with 30 minutes notice of an imminent strike in South Waziristan (but no advance notice for strikes in North Waziristan because the Haqqani Network enjoys such close ties with the ISI that the CIA fears their targets would be warned of the attack).

The focus on the FATA follows not only from the militant groups that are based there; it also derives from the exceptional legal status of the borderlands. Under British colonial rule, this was a buffer zone whose inhabitants were allowed a measure of nominal autonomy; colonial power was exercised indirectly through the authority vested in tribal leaders (who received subsidies from the British), and the special Frontier Crimes Regulations – in practice corrupt and draconian – were codified by Lord Curzon in 1901. After partition and independence in 1947 Pakistan retained the 1901 Regulations, so that the President – who has direct executive control of the FATA – appoints a Political Agent for each agency who has absolute authority to adjudicate criminal and civil affairs; ordinary Acts of Parliament do not apply to the FATA unless the President expressly declares that they do. Limited reforms were introduced in August 2011, including the right to political mobilisation, but some commentators raised doubts about their implementation. Preventive detention and collective punishment remain in force and the writ of the courts is still severely restricted.

These special measures were reinforced by the simultaneous passage of the Actions (in Aid of Civil Power) Regulations in 2011, a quid pro quo demanded by the military, which allowed the Pakistan Armed Forces to carry out ‘law enforcement duties [and] to conduct law enforcement operations’, granted them sweeping powers of pre-emptive arrest and detention without charge, and forbade the high court from intervening. According to one local politician, these new Regulations are ‘even more dangerous’ than the Frontier Crimes Regulations: ‘It is a system of martial law over the Tribal Areas.’ A new report from Amnesty International (from which I’ve taken these accounts) borrows its title, The Hands of Cruelty, from a despairing claim made by a lawyer from Peshawar: ‘The hands of cruelty extend to the Tribal Areas, but the hands of justice cannot reach that far.’

These special measures were reinforced by the simultaneous passage of the Actions (in Aid of Civil Power) Regulations in 2011, a quid pro quo demanded by the military, which allowed the Pakistan Armed Forces to carry out ‘law enforcement duties [and] to conduct law enforcement operations’, granted them sweeping powers of pre-emptive arrest and detention without charge, and forbade the high court from intervening. According to one local politician, these new Regulations are ‘even more dangerous’ than the Frontier Crimes Regulations: ‘It is a system of martial law over the Tribal Areas.’ A new report from Amnesty International (from which I’ve taken these accounts) borrows its title, The Hands of Cruelty, from a despairing claim made by a lawyer from Peshawar: ‘The hands of cruelty extend to the Tribal Areas, but the hands of justice cannot reach that far.’

(Given the – I think abusive – attack on Amnesty’s report by Abdullah Mansoor at Global Research as ‘malicious’ and ‘misinformation’ that virtually ignores the violence perpetrated by the Taliban and other militant groups, I should also draw readers’ (and his) attention to Amnesty’s previous report, As if Hell fell on me, which provides a detailed indictment of exactly that).

In short, the FATA constitute a space of exception in precisely the sense given to that term by Giorgio Agamben: the normal rights and protections under the law are withdrawn from a section of the population by the law. To see what this has to do with the geography of US drone strikes we can turn to an attack on 19 November 2008 on a residential compound in Indi Khel, 22 miles outside Bannu and about two hours by road from Peshawar. Five alleged militants were killed and four civilians injured: not a large toll compared to other strikes, and yet the public reaction across Pakistan was extraordinary.

A diplomatic cable from US Ambassador Anne Patterson on 24 November explained the widening gap between what she called ‘private GOP [Government of Pakistan] acquiescence and public condemnation for U.S. action’:

‘According to local press, the alleged U.S. strike in Bannu on November 19 marked the first such attack in the settled areas of the Northwest Frontier Province, outside of the tribal areas. The strike drew a new round of condemnation by Prime Minister Gilani, coalition political parties, opposition leaders, and the media.

‘According to Pakistani press, the strike killed four people, including a senior Al-Qaida member, and injured five others. The first strike within “Pakistan proper” is seen as a watershed event, and the media is suggesting this could herald the spread of attacks to Peshawar or Islamabad. Even politicians who have no love lost for a dead terrorist are concerned by strikes within what is considered mainland Pakistan.’

The language is truly extraordinary, with its distinction between the FATA and ‘Pakistan proper’, even ‘mainland Pakistan’. In short: (imaginative) geography matters. Not for nothing are the FATA known in Urdu as ilaqa ghair, which means ‘alien’ or ‘foreign’ lands.

The plight of the people in the FATA is exacerbated by the forceful imposition of a second, transnational legal regime: the right asserted by the United States to carry its fight against al Qaeda and its war against the Taliban across the border from the ‘hot’ zone in Afghanistan into militant sanctuaries in Pakistan. This is part of a larger argument about the advanced deconstruction of the traditional, bounded battlefield – here Frédéric Megret‘s work is indispensable – and the production of a global battlespace, processes that have been accelerated by the remote operations permitted by drones. But it remains both an assertion and an argument. Although international law is not a deus ex machina, a neutral court of appeal above the fray, it nonetheless has a developed body of precepts that are supposed to regulate armed conflicts between states, and there are also protocols and tribunals that govern armed conflicts between governments and non-state actors within the territorial boundaries of a state (the former Yugoslavia or Ruanda, for example). But conflicts between states and transnational non-state actors pose new and difficult questions, and perhaps even map a ‘legal void’. Significantly, as Eyal Benvenisti points out in the Duke Journal of International and Comparative Law,

‘Concurrently with the successful efforts to impose restraints on intra-state asymmetric warfare, we have been witnessing efforts by the same powerful countries that pressed for intra-state conflict regulation to deregulate inter-state asymmetric warfare or what may be called “transnational” warfare.‘

I will leave a review of these debates, at once legal and political, for another day; among the most relevant recent contributions are Kenneth Anderson, ‘Targeted killing and drone warfare: how we came to debate whether there is a legal geography of war’ (2011), available here; Laurie Blank, ‘Defining the battlefield in contemporary conflict and counterterrorism: understanding the parameters of the zone of combat’, Georgia Journal of International and Comparative Law 39 (1) (2010-11), available here; Jennifer Daskal, ‘The geography of the battlefield: a framework for detention and targeting outside the “hot” conflict zone’ (2012), available here; Noam Lubell and Nathan Derejko, ‘A global battlefield? Drones and the geographical scope of armed conflict’, Journal of International Criminal Justice 11 (1) (2013) 65-88 (abstract here). In this twilight zone, where Washington at once admits its actions through a never-ending string of off-the-record briefings and yet denies any responsibility for their collateral outcomes, there are no inquiries into ‘mistakes’, no culpability for wrong-doing, and no compensation or restitution for the innocent victims.

Whatever you make of the rights and wrongs of all this, what matters for my present purposes is that these two legal regimes, one national and the other transnational, work in concert to expose the people of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas to military and paramilitary violence and, ultimately, death.

It’s more than a matter of law, of course (and in any case we shouldn’t confuse legality with legitimacy). Within these exceptional spaces there has been active, tactical collaboration between the US and Pakistan. Another diplomatic cable reported a meeting on 22 January 2008 with General Kayani, who asked US Central Command to provide ‘continuous Predator coverage of the conflict area’ in South Waziristan, but was offered only Joint Terminal Attack Controllers to direct PAF air strikes by F-16s – an offer which was refused because of a reluctance to allow US ground forces to operate inside Pakistan. But in September and October 2009 small teams of US Special Forces were deployed to provide intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) support to the Pakistan Army, which included a ‘live downlink of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) full motion video.’ (What is interesting about all these exchanges is the degree of collaboration they reveal not only between the US and Pakistan but also between the CIA and the US military, especially Joint Special Operations Command; this is not surprising, given the hybridisation of military and paramilitary violence and the close involvement of the military in supplying, servicing and even flying the drones used in CIA-directed strikes).

There have been several reports of continuing collaboration between American and Pakistani intelligence operatives working on the ground in Pakistan, and one source – who purported to run a network of agents and ‘spotters’ in North and South Waziristan – told Reuters in January 2012 that ‘Our working relationship is a bit different from our political relationship. It’s more productive.’ He claimed that the US and Pakistan agreed priority target lists between them, and that it took little more than two or three hours between the location of a targeted individual and the firing of missiles. These claims are impossible to verify, but the emphasis on a working relationship rings true.

Perhaps the most chilling of the Wikileaks cables is this (redacted) message sent from Islamabad in February 2009, reporting a discussion with a senior member of the FATA Secretariat, who enthusiastically recommended the practice of ‘double tap‘ – follow-up strikes targeting rescuers – and endorses the rationale for signature strikes against unknown, un-named targets:

Perhaps the most chilling of the Wikileaks cables is this (redacted) message sent from Islamabad in February 2009, reporting a discussion with a senior member of the FATA Secretariat, who enthusiastically recommended the practice of ‘double tap‘ – follow-up strikes targeting rescuers – and endorses the rationale for signature strikes against unknown, un-named targets:

9. (S) XXXXXXXXXXXX remains a strong advocate of U.S. strikes. In fact, he suggested to PO that the U.S. consider follow-on attacks immediately after an initial strike. He explained that after a strike, the terrorists seal off the area to collect the bodies; in the first 10-24 hours after an attack, the only people in the area are terrorists, so “you should hit them again-there are no innocents there at that time.” His sources report that the reported September 29 strike in South Waziristan had been particularly successful; “you will see that you hit more than has been reported in the press both in terms of quantity and quality.” XXXXXXXXXXXX also drew a diagram essentially laying out the rationale for signature strikes…

Here you can see two perspectives on administrative killing, one from Pakistan and the other from the United States, converging onto a single target.

The cables from which I’ve quoted are all four or five years old, but this reflects the shutters coming down after the subsequent assault on Wikileaks and the arrest of Bradley Manning – the reports from seasoned investigative journalists are much more recent. I suppose you might conclude that none of them contradicts that artful word that does so much silent work in the official statement repeated by Emmerson, in which Pakistan denies reports of continuing tacit consent. But given what I’ve shown about the deadly dance over those five years, do you really think the music has stopped?

I’ve been contacted by L’actualité for an interview on drones, which led me to a new book by French philosopher Grégoire Chamayou (CNRS): Théorie du drone (La fabrique, 2013). I’ve only just ordered it, so this post is advance notice, the product of some rummaging around the web, and I’ll post a considered discussion as soon as I’ve read it.

I’ve been contacted by L’actualité for an interview on drones, which led me to a new book by French philosopher Grégoire Chamayou (CNRS): Théorie du drone (La fabrique, 2013). I’ve only just ordered it, so this post is advance notice, the product of some rummaging around the web, and I’ll post a considered discussion as soon as I’ve read it. You can find a short extract from Théorie du drone here. This is of particular interest to me since it includes a transcript of an air strike mediated but not directly carried out by a Predator crew and its associated network/assemblage in Uruzgan province, Afghanistan on 21 February 2010, which killed 23 civilians and wounded 8 others. It’s the mediation that is crucial, though I’m not (yet) sure that what Chayamou means by ‘intermediaries’ in the passage from RP above is quite what I have in mind: we’ll see. In any event, I discussed the strike and Major General Timothy McHale’s subsequent investigation in ‘From a view to a kill’ (DOWNLOADS tab) and I’ve now provided a much more detailed discussion, with longer extracts from the transcript Chamayou uses here, in The everywhere war (due to be finished, please God, this summer). Chamayou uses this incident as a Prelude to his main argument which – unlike so much philosophical reflection on later modern war, and as he makes clear in his Introduction is in part inspired by the example of Simone Weil – evidently engages directly with the material conduct of military violence.

You can find a short extract from Théorie du drone here. This is of particular interest to me since it includes a transcript of an air strike mediated but not directly carried out by a Predator crew and its associated network/assemblage in Uruzgan province, Afghanistan on 21 February 2010, which killed 23 civilians and wounded 8 others. It’s the mediation that is crucial, though I’m not (yet) sure that what Chayamou means by ‘intermediaries’ in the passage from RP above is quite what I have in mind: we’ll see. In any event, I discussed the strike and Major General Timothy McHale’s subsequent investigation in ‘From a view to a kill’ (DOWNLOADS tab) and I’ve now provided a much more detailed discussion, with longer extracts from the transcript Chamayou uses here, in The everywhere war (due to be finished, please God, this summer). Chamayou uses this incident as a Prelude to his main argument which – unlike so much philosophical reflection on later modern war, and as he makes clear in his Introduction is in part inspired by the example of Simone Weil – evidently engages directly with the material conduct of military violence.