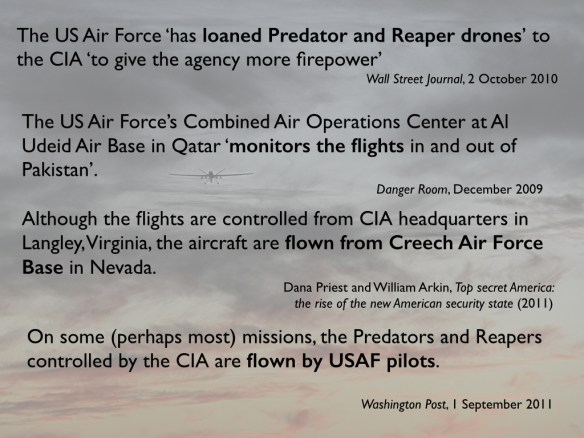

In the short-form version of ‘The everywhere war’ (DOWNLOADS tab) I emphasised the blurring of the lines between the increasingly paramilitary but nominally civilian CIA and the US military, and for the last several years I’ve been including this slide in most of my presentations about CIA-directed drone strikes in Pakistan (and I’ve been very careful to use precisely that description: ‘CIA-directed’):

Today’s Guardian (online) carries a report that lends support to these claims and concerns:

A regular US air force unit based in the Nevada desert is responsible for flying the CIA’s drone strike programme in Pakistan, according to a new documentary to be released on Tuesday.

The film – which has been three years in the making – identifies the unit conducting CIA strikes in Pakistan’s tribal areas as the 17th Reconnaissance Squadron, which operates from a secure compound in a corner of Creech Air Force Base, 45 miles from Las Vegas in the Mojave desert.

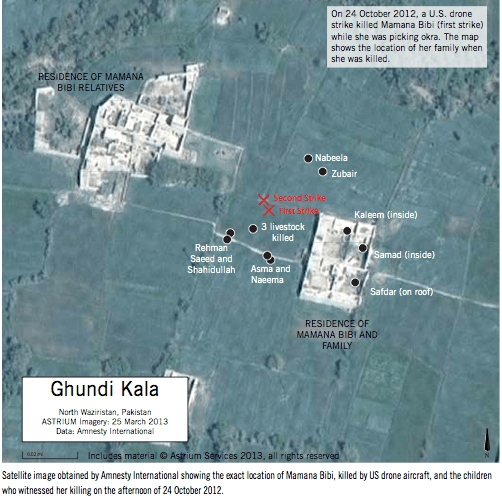

Several former drone operators have claimed that the unit’s conventional air force personnel – rather than civilian contractors – have been flying the CIA’s heavily armed Predator missions in Pakistan, a 10-year campaign which according to some estimates has killed more than 2,400 people.

The film is Tonje Schei‘s documentary Drone, which has its premiere tomorrow. You can read an interview with her about the drone wars here. In an overlapping interview for Pakistani media, she explains:

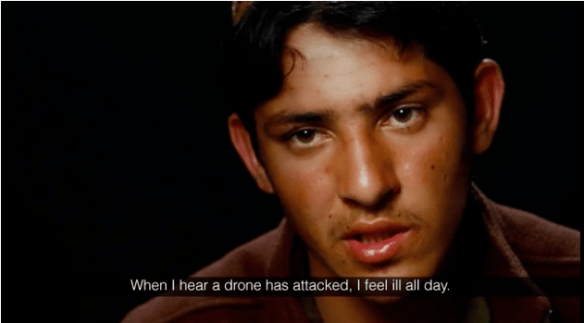

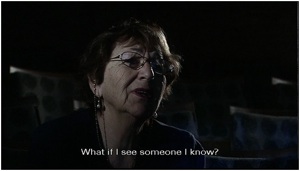

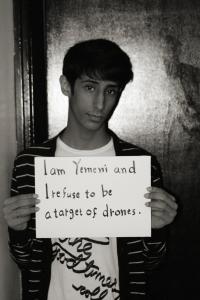

DRONE investigates the human consequences of the US drone war. Through unique access to voices on both sides of this new technology, DRONE offers new insights into the nature of drone warfare. DRONE juxtaposes the realities of drone victims in Waziristan to drone pilots who struggle to come to terms with the new warfare. The film covers diverse and integral ground from the recruitment of young pilots at gaming conventions and the re-definition of “going to war”, to the moral stance of engineers behind the technology, the world leaders giving the secret “greenlight” to engage in the biggest targeted killing program in history, and the people willing to stand up against the violations of civil liberties and fight for transparency, accountability and justice.

You can watch a clip on Youtube, which I’ve also embedded here, in which Chris Woods (senior reporter at the Bureau of Investigative Journalism) explains why this blurring of the lines between the CIA and the military matters:

Schei’s original source was Brandon Bryant, a former USAF sensor operator who had already gone public with his own account of the traumatic business of targeted killing (see also here and here). He decided to add to his testimony when the Obama administration proposed transferring control of the targeted killing program from the CIA to the military, a plan that has faced Congressional opposition:

“There is a lie hidden within that truth. And the lie is that it’s always been the air force that has flown those missions. The CIA might be the customer but the air force has always flown it. A CIA label is just an excuse to not have to give up any information. That is all it has ever been.”

Bryant’s account has apparently been corroborated by another six former crew members, who claimed that the 17th transitioned to its ‘new customer’ in 2004.

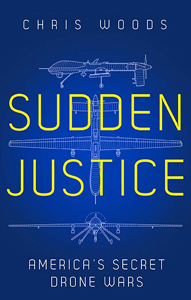

Chris Woods provides much more in Sudden Justice: America’s secret drone wars, forthcoming from Hurst at the end of this year, but – for now – here is what I said in ‘The everywhere war’ in 2011 (and I can now say much more in The everywhere war!):

Chris Woods provides much more in Sudden Justice: America’s secret drone wars, forthcoming from Hurst at the end of this year, but – for now – here is what I said in ‘The everywhere war’ in 2011 (and I can now say much more in The everywhere war!):

These considerations radically transform the battlespace as the line between the CIA and the military is deliberately blurred. Obama’s recent decision to appoint Panetta as Secretary of Defense and have General David Petraeus take his place as Director of the CIA makes at least that much clear. So too do the braiding lines of responsibility between the CIA and Special Forces in the killing of Osama bin Laden in Abbottabad in May 2011, which for that reason (and others) was undertaken in what Axe (2011) portrays as a ‘legal grey zone’ between two US codes, Title 10 (which includes the Uniformed Code of Military Justice) and Title 50 (which authorises the CIA and its covert operations) (Stone 2003). The role of the CIA in this not-so-secret war in Pakistan thus marks the formation of what Engelhardt and Turse (2010) call ‘a new-style [battlespace] that the American public knows remarkably little about, and that bears little relationship to the Afghan War as we imagine it or as our leaders generally discuss it’.