Last week I had a wonderful time at the Eisenberg Institute for Historical Studies at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and came away with a host of new ideas and fresh lines of inquiry.

One of these concerns the role of the telegraph in modern war. When I was doing my first researches I discovered several writers emphasised its importance in reporting the Crimean War (1853-1856), a campaign that saw the first appearance of the war correspondent in the person of W.H. Russell, whose despatches for the Times won him a central place in both political and media history.

One of these concerns the role of the telegraph in modern war. When I was doing my first researches I discovered several writers emphasised its importance in reporting the Crimean War (1853-1856), a campaign that saw the first appearance of the war correspondent in the person of W.H. Russell, whose despatches for the Times won him a central place in both political and media history.

In The Ultimate Spectacle: a visual history of the Crimean War (Routledge, 2001) Ulrich Keller argued that:

‘Throughout the campaign the domestic front continuously inscribed itself on the military front, and vice versa; nothing could happen in one sphere without immediate repercussions in the other. It was of course the steamship, the telegraph and the news-press with its swift coverage of events, which created the interdependence of the two arenas.

‘Without the dramatic improvement of communication technologies during the first half of the nineteenth century, the Crimean events, evolving at a distance of 3000 miles from London, could never have become an object of constant, close and emotional public scrutiny at home…’

Russell’s reports were of tremendous significance, and the telegraph was important for the conduct of the war. Indeed, Orlando Figes in Crimea: the last Crusade (Allen Lane, 2010) treats the Crimean War as

‘the first example of a truly modern war – with new industrial technologies, modern rifles, steamships and railways, novel forms of logistics and communication like the telegraph .. and war reporters and photographers directly on the scene.’

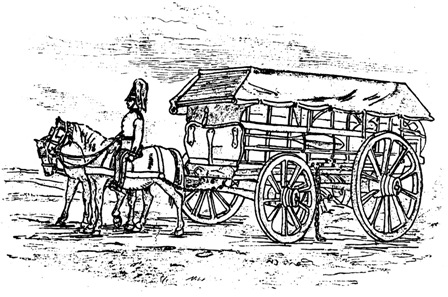

But it is important not to confuse the two. The British Army had a field telegraph whose 24 mile network connected Lord Raglan’s headquarters with eight stations in the field. The illustration below comes from Steven Roberts‘s Distant Writing which is a tremendous source of information on British telegraph companies from 1838 to 1868:

Electric Telegraph Company’s War Wagon in the Crimea, 1854

In addition, Army dispatches were sent 300 miles across the Black Sea to Varna and then overland to Bucharest (a journey of 60 hours) where they were telegraphed to London; by April 1855 a temporary submarine cable from Balaklava to Varna had reduced the overall transmission time to London to 5 hours, and the press used the same line for sending short despatches to London. One periodical was so excited at the new proximity of war that it held out the fantasy

‘that it would not now be difficult, by some little farther novelty of invention, to cause the reverberation of the very cannons themselves, as it were, to be transmitted, in the shape of electric vibration, through the 3000 miles of intervening wire, and heard, in still continuous vibrations, finally communicated to some acoustic apparatus in the British Houses of Parliament…. There is no physical reason why the public should not know every morning, noon and night, what is at these very times going on in the seat of war.’

But Russell’s detailed despatches went by sea via Constantinople and took 20 days to reach London: his famous report of the Charge of the Light Brigade on 25 October 1854 was not published in the Times until 13 November, though an initial notice had appeared on 2 November. And so it was not Russell that the Earl of Clarendon, the Foreign Secretary [right], had in his sights when he wrote to the British Ambassador in Constantinople on 23 September 1854, a month before that epic encounter (and in fact before any of Russell’s reports had been published), to complain about the press:

But Russell’s detailed despatches went by sea via Constantinople and took 20 days to reach London: his famous report of the Charge of the Light Brigade on 25 October 1854 was not published in the Times until 13 November, though an initial notice had appeared on 2 November. And so it was not Russell that the Earl of Clarendon, the Foreign Secretary [right], had in his sights when he wrote to the British Ambassador in Constantinople on 23 September 1854, a month before that epic encounter (and in fact before any of Russell’s reports had been published), to complain about the press:

‘Our “own correspondents” have certainly contrived to keep our enemy informed of all he must want to know – his only disadvantage is 8 hours delay which is the time for transmitting to St P[etersburg] all that the newspapers contain and they generally publish as much as the Government knows for in one way or another some correspondent at Hd Qrs generally discovers and transmits every secret order or intended movement as well as every disaster and disharmony and the patriotic editors never think of keeping back anything injurious to the public service but on the contrary hasten to publish it all in proof of their superior means of intelligence. The press and the telegraph are enemies we had not taken into account but as they are invincible there is no use complaining about them.’

What he had in mind were the brief telegraphic despatches that were mined by all the leading newspapers in Britain. The Times was no exception, but it prided itself on its exclusive reports from Russell [left], as it explained on 21 October 1854:

What he had in mind were the brief telegraphic despatches that were mined by all the leading newspapers in Britain. The Times was no exception, but it prided itself on its exclusive reports from Russell [left], as it explained on 21 October 1854:

‘The letters of our special correspondent from the scene of war, although naturally a few days in arrear of those leading communications which reach us through the agency of the telegraph, are always replete with interest, and are calculated indeed to serve far more important purposes than those of momentary amusement. In those circumstantial descriptions of an eye-witness – in those details of actual experience and personal observation – we obtain an inexhaustible source of information… We not only learn step by step what the army really did, and where it went, but we follow it in its march, and collect the opinions, the hopes and the feelings current among the soldiery from hour to hour.’

It may be true to say, as Andrew Lambert wrote for the BBC, that ‘the electric telegraph enabled news to travel across the continent in hours, not weeks’ so that during the Crimea ‘war became much more immediate – a massive leap forward on the way to our age of instant global coverage by satellite.’ But beyond Europe reporting was still agonisingly slow. In Australia, as Peter Putnis and Sarah Ailwood have shown, ‘just when news from Europe was most eagerly wanted’, steamship services from Britain were diverted to supply troop ships for the war, and the replacement sailing packets were so much slower and less reliable that colonial insecurities were heightened. And even within Europe Lambert’s ‘immediacy’ was produced by terse and not always reliable telegraphic despatches that editors combined with long-form reports from their correspondents and others in the field. The most vivid images of the war were produced by Russell’s despatches and by Roger Fenton‘s striking photographs.

For this reason, until now I had thought of the American Civil War (1861-1865) as ‘the first telegraph war‘, since the telegraph was demonstrably important both for the conduct of the war (which included military communications and, since cables were intercepted, military intelligence) and for its more detailed reporting.

But at Ann Arbor I met the redoubtable Jonathan Marwil who directed my attention to the Second Italian War of Independence (sometimes called the Franco-Austrian War) of 1859. His Visiting modern war in Risorgimento Italy (Palgrave, 2010), which I’ve devoured on my Kindle, is a superb account of the mediatization of modern war. By 1859, he writes,

But at Ann Arbor I met the redoubtable Jonathan Marwil who directed my attention to the Second Italian War of Independence (sometimes called the Franco-Austrian War) of 1859. His Visiting modern war in Risorgimento Italy (Palgrave, 2010), which I’ve devoured on my Kindle, is a superb account of the mediatization of modern war. By 1859, he writes,

‘armies could not expect to wage wars without journalists in attendance. Their stories, composed from what they saw, what they were told, and what they imagined, would be read soon after they were written, given the proximity of the seat of war to the major capitals and the presence of the telegraph wire. Those watching a war from afar were now kept abreast of events almost while they were happening. News of the first Napoleon’s victories in Italy had taken days to reach Paris; reports of his nephew’s expected triumphs would arrive in hours. A day after a major battle in early June, a French lieutenant would write his uncle assuming that he already knew more about the battle than did the nephew who had fought in it.’

[That last remark, incidentally, recalls one of the core arguments of Jan Mieszkowski‘s Watching War (Stanford University Press, 2012): that one of the crucial dilemmas of modern war is the disconnect between the participant’s sensory disorientation (‘To be under fire is to experience the loss of control of one’s own signifying practices’) and the abstraction (or ‘perspective’) of distant observers.]

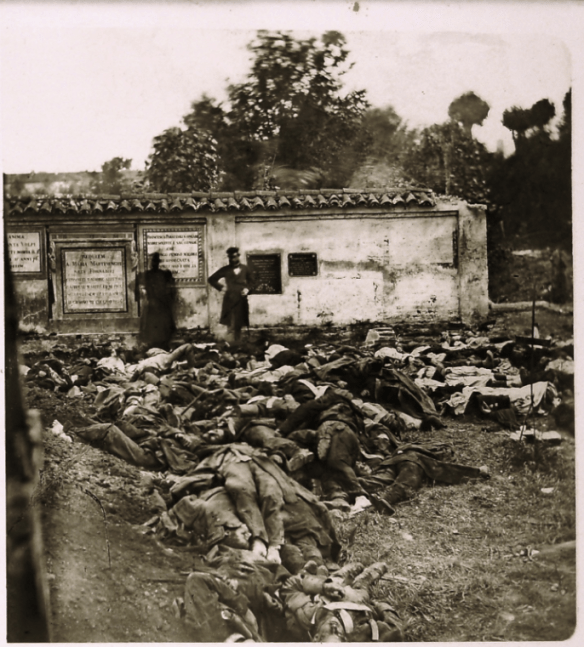

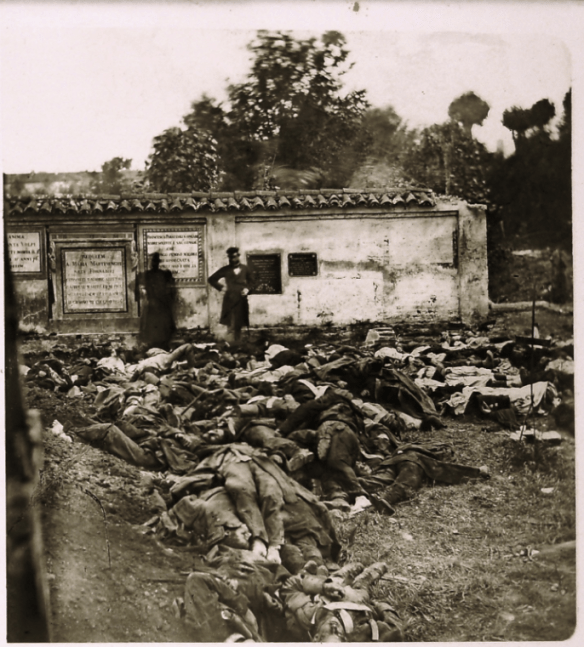

The Italian War was a war of truly awful proportions: you can find a stark description of ‘combat photography’ during the war, together with some examples, at Bill Johnson‘s Hold History in Your Hand here. At the battle of Solferino some 40,000 were killed or injured in 15 hours, and the sight of the unrelieved suffering prompted a Swiss observer, Henry Dunant, to memorialise the scene in A memory of Solferino. Within months of its publication in 1862 a committee started work on Dunant’s vision of an impartial relief society that would provide aid to those wounded in time of war: this would eventually become the International Committee of the Red Cross.

Cemetery at Melegnano, June 1859

The Times was horrified at what it called ‘the wanton and prodigal waste of life’ too, but in an editorial on 2 June 1859 it also reflected on the intimate conjuncture of killing and technological advance:

‘… revolting as war always is, it never presented itself in a form more repulsive than that which it now wears in the Italian Peninsula… War also seems to have become more hideous from its closer contact with the greatest triumphs of our modern civilization. The butchery of Casteggio was fed by a succession of railway trains, which disgorged their cargoes close to the human shambles, just as they carry the cattle, the sheep, and the calves which feed the daily hunger of London.

‘Science is degraded into an instrument for .. destruction… While rival hosts are encountering each other with a ferocity which the Huns and the Vandals might envy, news of every particular of the butchery is carried by the delicate and beautiful machinery of the electric telegraph, and the pulse with which all nature throbs communicates, with a fidelity and despatch unknown to the Scourge of Mankind in former ages, every circumstance and detail of destruction.’

(Polity, 2012/13):

(Polity, 2012/13):