On the day that Bradley Manning has been found guilty, here is John Pilger‘s celebrated film on the mediatization of modern war: a timely reminder of what, without people like Manning, we would never see and never know:

Category Archives: media

Writing at a dead-line

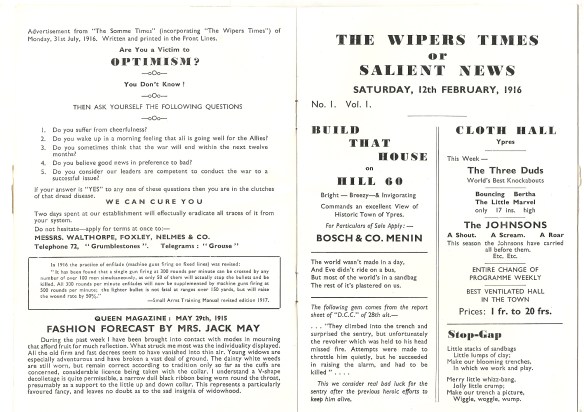

Back in the trenches again, revising “Gabriel’s Map”, and I see that the former President of the Royal Geographical Society – rather better known as Michael Palin (“This President is no more! He has ceased to be…. This is an EX-PRESIDENT!!”) – appears in a new BBC2 drama [also starring Ben Chaplin and Emilia Fox, left] based on the story of The Wipers Times, a trench newspaper written and printed on the Western Front during the First World War.

Back in the trenches again, revising “Gabriel’s Map”, and I see that the former President of the Royal Geographical Society – rather better known as Michael Palin (“This President is no more! He has ceased to be…. This is an EX-PRESIDENT!!”) – appears in a new BBC2 drama [also starring Ben Chaplin and Emilia Fox, left] based on the story of The Wipers Times, a trench newspaper written and printed on the Western Front during the First World War.

This is Palin’s first dramatic role in twenty years (other then being President of the RGS). Many readers will no doubt immediately think of the far from immortal Captain Blackadder in Blackadder Goes Forth (in which case see this extract from J.F. Roberts‘ The true history the Blackadder – according to Rowan Atkinson, “Of all the periods we covered it was the most historically accurate” – and compare it with this interview with Pierre Purseigle).

But since the script for The Wipers Times has been co-written by Ian Hislop (with Nick Newman) the Times is inevitably being described as a sort of khaki Private Eye: Cahal Milmo in the Independent says that ‘its rough-and-ready first edition was a masterclass in the use of comedy against industrialised death and military officialdom.’

So it was, but the appropriate critical comparison is with Punch, which Esther MacCallum-Stewart pursues in ingenious depth here. The French satirical magazine Le canard enchaîné (which is in many ways much closer to the Eye) started publication in 1915 and was much more critical. But for most of the war, MacCullum-Stewart says, Punch enforced ‘a strict code of “comedy as usual” interspersed by patriotic statements which hardly pastiched anything except an enduring capacity for the British to show a stiff upper lip to all comers.’

That soon wore thin on the Western Front, and when Captain Fred Roberts – played by Chaplin – found a printing-press amongst the rubble of Ypres (“Wipers”) in February 1916 the Times was born (though a shortage of vowels meant that only one page could be set up and printed at a time).

The title of the paper changed as the Division was re-deployed time and time(s) again. It had many targets in its sights, including the warrior poets:

‘We regret to announce that an insidious disease is affecting the Division, and the result is a hurricane of poetry. Subalterns have been seen with a notebook in one hand, and bombs in the other absently walking near the wire in deep communication with their muse.’

This is one of the most widely quoted passages in the paper, but MacCallum-Stewart explains that this is precisely because it could be squared with the mythology of the war which so many other contributions worked to undermine.

You can find other extracts here but my favourite – given how mud works its way into a central place in “Gabriel’s Map” and into one of the vignettes in “The nature of war” – is this satirical version of Rudyard Kipling‘s If (Kipling wrote the original in 1909 as advice to his son –”If you can keep your head when all about you are losing theirs…”: celebrated by the Daily Mail here):

If you can drink the beer the Belgians sell you,

And pay the price they ask with ne’er a grouse,

If you believe the tales that some will tell you,

And live in mud with ground sheet for a house,

If you can live on bully and a biscuit.

And thank your stars that you’ve a tot of rum,

Dodge whizzbangs with a grin, and as you risk it

Talk glibly of the pretty way they hum,

If you can flounder through a C.T. nightly

That’s three-parts full of mud and filth and slime,

Bite back the oaths and keep your jaw shut tightly,

While inwardly you’re cursing all the-time,

If you can crawl through wire and crump-holes reeking

With feet of liquid mud, and keep your head

Turned always to the place which you are seeking,

Through dread of crying you will laugh instead,

If you can fight a week in Hell’s own image,

And at the end just throw you down and grin,

When every bone you’ve got starts on a scrimmage,

And for a sleep you’d sell your soul within,

If you can clamber up with pick and shovel,

And turn your filthy crump hole to a trench,

When all inside you makes you itch to grovel,

And all you’ve had to feed on is a stench,

If you can hang on just because you’re thinking

You haven’t got one chance in ten to live,

So you will see it through, no use in blinking

And you’re not going to take more than you give,

If you can grin at last when handing over,

And finish well what you had well begun,

And think a muddy ditch’ a bed of clover,

You’ll be a soldier one day, then, my son.

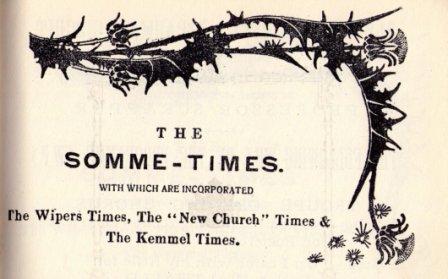

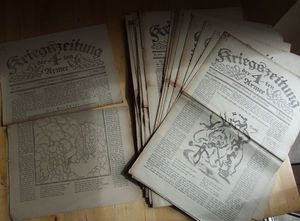

There were many other trench newspapers produced by the different armies on both sides. On the Allied side there were 100 or so British ones, for example, and perhaps four times as many French ones; there were perhaps 30 Canadian ones, and more Australian ones. Graham Seal has just published the first full-length study of Allied trench newspapers: The soldier’s press: Trench journals in the First World War (Palgrave-Macmillan 2013); you can sneak an extensive peak on Google Books (though contrary to what it says there, an e-edition is available at a ruinous price). As you can see from the image above, there were also trench newspapers on the other side too: see Robert Nelson, German soldiers newspapers of the First World War (Cambridge University Press, 2011). He also wrote a more general and thoroughly accessible survey of trench newspapers in War & History [2010] which is available here.

In the final edition of the Times, published after the end of the war, Roberts – by then a Lieutenant-Colonel – wrote this:

“Although some may be sorry it’s over, there is little doubt that the linemen are not, as most of us have been cured of any little illusions we may have had about the pomp and glory of war, and know it for the vilest disaster that can befall mankind.”

Producing the public in Arab societies

More news from Paul Amar about the inaugural research program launched by the Arab Council of Social Sciences (headquartered in Beirut; more at Jadaliyya here) on ‘Producing the Public in Arab Societies: space, media, participation.’

Formulating new understandings of public life in societies within conditions of twenty- first century globalization is an urgent priority for the social sciences. The insecurity of global and national financial systems, the increased violence and securitization of social and political life and the new modes and practices of making collective and social/cultural claims require rethinking concepts such as the “public sphere,” “public culture,” “public institutions,” “public access (e.g. to information)” and “the public good.” In addition, calls within some disciplines for the importance of “public knowledge” (e.g. “public sociology” and “public anthropology”) means that the social sciences themselves are part, and not only observers and analyzers, of re- conceptualizing public life. Knowledge production in general is integral to the development and maintenance of a vibrant public sphere in which different opinions, identities and political positions can be explored without recourse to violence. At least this is the hope embedded in these reformulations.

In this context, the Arab Council of the Social Sciences (ACSS) is launching a research program entitled “Producing the Public in Arab Societies,” that will enable projects to examine political, social and cultural issues in relation to one another while focusing on specific topics. This multidisciplinary program will explore the new possibilities, spaces and means for political action and practice in different Arab societies that bring to light, and create, new publics. The political and social imaginaries that are being produced not only open up new futures but also reread histories and reconfigure relations between different groups and actors in society, including the relationship between the intelligentsia and the rest of society. The retaking and remaking of the state, the new modes of inclusion and exclusion and the role of diasporas are among the issues raised by this research program. All these processes have profound implications for the societies in question but also for the social sciences in general.

The Program will consist of three Working Groups, one focusing on space, another on media, and a third on participation. These three Working Groups will be relatively autonomous, but will engage in regular dialogue with each other, occasionally come together for joint meetings; and they may develop cross-cutting research collaborations or products. In addition, there may be opportunities for cross-regional collaboration with researchers in Asia, Africa and Latin America.

Paul will co-ordinate the working group on Space, Tarik Sabry the working group on media, and Sherene Seikaly the working group on participation.

Here is the summary prospectus for the Space working group:

“Producing the Public: Spaces of Struggle, Embodiments of Futurity” This Working Group will research public spaces and spatializing embodiments that reverse class, sectarian, and gender segregation, foster social equalization, revive previous intersectional public subjectivities, and/or create future utopias. Our research will explore the context and legacies of the “Arab Spring”-era events; but we will largely (but not exclusively) focus on countries identified more with war and counterrevolution rather than with the triumphant social uprisings of 2011. Thus we aim to bridge gaps between analyses of spaces of war and armed intervention (in Syria, Libya, Iraq, Bahrain, etc.), and embodiments of future hope, inclusion, and justice across the Arab region.

Very exciting work has been done in the last generation shedding critical light on regimes of power, cultures of fear, and technologies of planning that have transformed public spaces. This work has focused on deconstructing neoliberal policies and discourses, exposing the techniques and economies of war and occupation, and articulating the spatial dimensions of postcolonial moral, ethno-sectarian, and religious regimes. This generation of scholarship has asked: How have social classes have been polarized by new kinds of space and public morality; how have built forms and spatial performances exacerbated sectarian divisions or even “invented” them; how have regimes of public-space regulation instituted regimes of puristic or pietist morality; and how have shifting norms of public-versus-private space restricted gender identities and issues of sexuality to an ever-narrowing private sphere where consumer and patriarchal values dominate. However, this set of research innovations have tended to neglect the kinds of spatial practices, movements, public embodiments, and policy regimes that can reverse or generate spatial alternatives that counter these segregatory dynamics and territorialization practices. In this light, “Producing the Public: Spaces of Struggle, Embodiments of Futurity” aims to produce a new body of comparative case studies. This Working group will be oriented explicitly toward positive alternatives, even in the most fraught contexts, and will offer new analyses of spatial and historical relations of power, war, control, and subjectivation.

Paul is particularly keen to include scholars working on Libya, though anyone who meets the critera (below) is welcome to apply. Questions about the Space working group to Paul at amar@global.ucsb.edu and about the program in general to grants@theacss.org.

Working group meetings start in September; those participating will receive full support for travel to and accommodations at all research workshops/group meetings, which will be held twice per year (usually held in the Arab Region or perhaps in Cyprus or Turkey), together with around $10,000 in research funds. This is a marvellous and rare opportunity, and so not surprisingly the criteria are stringent:

1) Due to the specialized mandate of the ACSS itself, all applicants must be either (1) a current or former citizen of one of the member states of the League of Arab States; OR (2) of Arab origin or part-Arab descent (or of any other ethnic, national, sectarian or minority “identity” within any Arab League country). Applicants who meet the above criteria and are living in the Arab region are encouraged to apply. Those living outside the Arab region are also welcome to apply, but they should demonstrate that they spend a significant part of each year in the region, engaged substantively with publics in a particular site, and be fully committed to public movements, cultures, and organizations in the region.

2) Applicants for the “Space” Working Group must be either in the final stages of receiving their PhD (“ABD” or prospectus finished), or be a professor or lecturer in the first seven years after completing their PhD. Applicants should have a social science degree, or a degree in a field within the “humanistic social studies” such as history, cultural studies, legal studies, etc.

3) Applicants for the “Participation” Working Group can be practitioners, media workers, journalists, techies, and scholars engaged in participatory work that both critiques and engages social sciences in the Arab world.

4) Applicants for the “Media” Working Group should have a degree in the ‘humanistic social sciences’. They will need to have published and conducted research in the Arab region, focusing on the relationships between media, culture and society. They will also be expected to think beyond disciplinary boundaries by engaging critically with scholars specializing in different fields of the humanities and the social sciences, including anthropology, media studies, cultural studies and philosophy. They must also be fluent in Arabic.

5) All applicants should be proficient in Arabic as well as English and/or French. Much of the readings and some of the conversations will be conducted in English, due to the overwhelming use of English in the relevant academic, political, and technical literatures. However ACSS encourages and permits writings and publications in Arabic, French or English. And each group will, of course, constantly engage public expressions, leaders, and research meetings in Arabic.

Incidentally, anyone who finds the idea of ‘producing’ the public an unfamiliar one should read Michael Warner‘s classic work, The letters of the Republic: publication and the public sphere in eighteenth-century America; you can also find a snappy essay by him, ‘Publics and counterpublics’, at Public culture (2002). As this suggests, so many of the available models and substantive treatments of these issues traffic in the public spheres of Europe and the shadows of Habermas, and it will be exceptionally interesting to see what happens when the focus and language of the discussion travels beyond these too familiar waters and also addresses the formation of transnational public spheres. And I’m also drawn to the way in which Paul’s working group will move the research frontier towards sites of war, counter-revolution and resistance. Do contact him if you’re interested.

Tahrir Squared

I’ve been putting the finishing touches to the extended version of my essay on Tahrir Square and the Egyptian uprisings, which focuses on performance, performativity and space through an engagement with Judith Butler‘s ‘Bodies in alliance and the politics of the street’ essay/lecture (originally delivered in Venice in 2011).

Much of the existing discussion of Tahrir treats performance in conventional dramaturgical terms, and owes much more to Erving Goffman‘s classic work than to Judith’s recent contributions, so that spatiality is more or less reduced to a stage: see, for example, Charles Tripp, ‘Performing the public: theatres of power in the Middle East’, Constellations (2013) doi: 10.1111/cons.12030 (early view). Others have preferred to analyse the spatialities of Tahrir through the work of Henri Lefebvre: I’m thinking of Ahmed Kanna, ‘Urban praxis and the Arab Spring’, City 16 (3) (2012) 360-8; Hussam Hussein Salama, ‘Tahrir Square: a narrative of public space’, Archnet – IJAR 7 (1) (2013) 128-38;and even, en passant, W.J.T.Mitchell, ‘Image, space, revolution: the arts of occupation’, Critical Inquiry 39 (1) (2012) 8-32.

Much of the existing discussion of Tahrir treats performance in conventional dramaturgical terms, and owes much more to Erving Goffman‘s classic work than to Judith’s recent contributions, so that spatiality is more or less reduced to a stage: see, for example, Charles Tripp, ‘Performing the public: theatres of power in the Middle East’, Constellations (2013) doi: 10.1111/cons.12030 (early view). Others have preferred to analyse the spatialities of Tahrir through the work of Henri Lefebvre: I’m thinking of Ahmed Kanna, ‘Urban praxis and the Arab Spring’, City 16 (3) (2012) 360-8; Hussam Hussein Salama, ‘Tahrir Square: a narrative of public space’, Archnet – IJAR 7 (1) (2013) 128-38;and even, en passant, W.J.T.Mitchell, ‘Image, space, revolution: the arts of occupation’, Critical Inquiry 39 (1) (2012) 8-32.

None of these seem to me to convey the way in which, as Judith has it, the presence of bodies in the square becomes the performance of a new spatiality through which people

‘seize upon an already established space permeated by existing power, seeking to sever the relation between the public space, the public square, and the existing regime. So the limits of the political are exposed, and the link between the theatre of legitimacy and public space is severed; that theatre is no longer unproblematically housed in public space, since public space now occurs in the midst of another action, one that displaces the power that claims legitimacy precisely by taking over the field of its effects…. In wresting that power, a new space is created, a new “between” of bodies, as it were, that lays claim to existing space through the action of a new alliance, and those bodies are seized and animated by those existing spaces in the very acts by which they reclaim and resignify their meanings.’

I see a similar conception at work in Adam Ramadan‘s emphasis on Tahrir as at once a space and an act – a space-in-process, if you like – of encampment: ‘From Tahrir to the world: the camp as a political public space’, European Urban and Regional Studies 20 (2013) 145-9. I’m drawn to these formulations partly because they connect performance to the possibility of performativity through space-in-process, and partly because these ideas, attentive as they are to ‘space’, also pay close attention to ‘time’ (or rather space-time) (for a suggestive discussion of the temporalities of Tahrir, which I think have been marginalised in too many ‘spatialising’ discussions, see Hanan Sabea, ‘A “time out of time”‘, here.)

These comments are little more than place-holders, I realise, and I hope my reworked essay will clarify them; I’ll post the final version on the Downloads page as soon as it’s ready – in the next day or two, I hope. [UPDATE: The manuscript version, to appear in Middle East Critique, is now available under the DOWNLOADS tab: ‘Tahrir: politics, publics and performances of space’]

In the meantime, if you’re interested in the Egyptian uprisings, there’s an excellent online bibliography at Mark Allen Peterson‘s equally excellent Connected in Cairo here; Mark also provides a listing of documentary films here (including YouTube feeds).

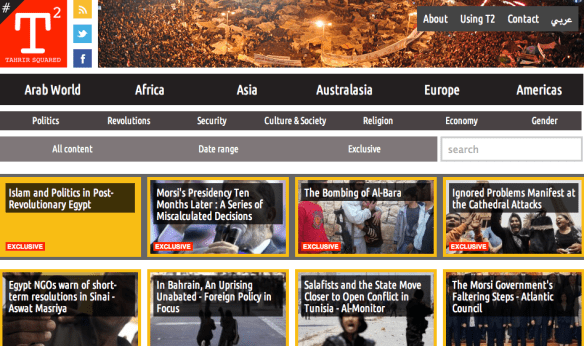

Part of my discussion addresses the imbrications of the digital and the physical, the virtual and the visceral. For a quick overview, see Mohamed Elshahed here (from whom I’ve borrowed the wonderful image at the head of this post), but for a remarkable online platform that, amongst other things, seeks to ‘multiply the Tahir Effect around the globe’, capitalising on the transformations from the digital to the physical and back again, try Tahrir Squared:

‘T2 is a one-stop shop for reliable and enlightening information about the Arab uprisings, revolutions and their effects. It combines both original content by leading analysts, journalists and authoritative commentators, and curated content carefully selected from across the web to provide activists, researchers, observers and policy makers a catch-all source for the latest on the Arab revolutions and related issues through an interactive, virtual multimedia platform.

Unattached to governments or political entities, Tahrir Squared is concerned with ‘multiplying the Tahrir Effect around the globe’: an Effect which reawakened civic consciousness and awareness. An Effect which led to neighbourhood protection committees, and created those scenes in Tahrir of different religions, creeds and backgrounds engaging, assisting, and protecting one another.

That Effect still lives inside those who believe in the ongoing revolutions that called for ‘bread, freedom, social justice and human dignity’. This website is a part of that broader initiative, seeking to provide people with the knowledge and information to assist and stimulate that process of reawakening, through the provision of reliable news reports, thoughtful commentary, and useful analysis.‘

Spaces of constructed (in)visibility

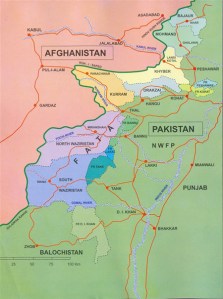

Further to my previous posts on air strikes in Pakistan here and here, the International Crisis Group today published a new report, Drones: Myths and Reality in Pakistan.

Further to my previous posts on air strikes in Pakistan here and here, the International Crisis Group today published a new report, Drones: Myths and Reality in Pakistan.

From ICG’s media release:

‘The report’s major findings and recommendations are:

- Pakistan’s new civilian leadership under PML-N leader Nawaz Sharif must make the extension of the state’s writ in FATA the centrepiece of its counter-terrorism agenda, bringing violent extremists to justice and thus diminishing Washington’s perceived need to conduct drone strikes in Pakistan’s tribal belt.

- Drones are not a long-term solution to the problem they are being deployed to address, since the jihadi groups in FATA will continue to recruit as long as the region remains an ungoverned no-man’s land.

- The U.S., while pressuring the Pakistan military to end all support to violent extremists, should also support civilian efforts to bring FATA into the constitutional and legal mainstream.

- The lack of candour from the U.S. and Pakistan governments on the drone program undermines efforts to assess its legality or its full impact on FATA’s population. The U.S. refuses to officially acknowledge the program; Pakistan portrays it as a violation of national sovereignty, but ample evidence exists of tacit Pakistani consent and, at times, active cooperation.

- Pakistan must ensure that its actions and those of the U.S. comply with the principles of distinction and proportionality under international humanitarian law. Independent observers should have access to targeted areas, where significant military and militant-imposed barriers have made accurate assessments of the program’s impact, including collateral damage, nearly impossible.

- The U.S. should cease any practices, such as “signature strikes”, that do not comply with international humanitarian law. The U.S. should develop a legal framework that defines clear roles for the executive, legislative and judicial branches, converting the drone program from a covert CIA operation to a military-run program with a meaningful level of judicial and Congressional oversight.

“The core of any Pakistani counter-terrorism strategy in this area should be to incorporate FATA into the country’s legal and constitutional mainstream”, says Samina Ahmed, Crisis Group’s Senior Asia Adviser. “For Pakistan, the solution lies in overhauling an anachronistic governance system so as to establish fundamental constitutional rights and genuine political enfranchisement in FATA, along with a state apparatus capable of upholding the rule of law and bringing violent extremists to justice”.

The report speaks directly to claims that the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) are treated by both Washington and Islamabad as a space of exception, subject to special legal dispensations that expose their inhabitants to military violence and, ultimately, death. And it also repeats much of the argument I made earlier about the close collaboration between Washington and Islamabad based, in part, on the Wikileaks cables.

The report speaks directly to claims that the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) are treated by both Washington and Islamabad as a space of exception, subject to special legal dispensations that expose their inhabitants to military violence and, ultimately, death. And it also repeats much of the argument I made earlier about the close collaboration between Washington and Islamabad based, in part, on the Wikileaks cables.

But there’s nothing about the air strikes carried out in the FATA by the Pakistan Air Force. Since the report is specifically about the CIA-directed counter-terrorism campaign, you may think the silence unsurprising. But I think it’s important not to contract the focus in this way – I say that not to exempt the US from criticism (far from it) but as a reminder that this is a space of constructed visibility that is also (as always) a space of constructed invisibility. The inhabitants of FATA deserve to have the wider landscape of military violence exposed to the public gaze.

As part of that process, this passage is immensely important, given the difficulty of reporting from or carrying out field work in the FATA:

‘Islamabad has a constitutional and international obligation to protect the lives of citizens and non-citizens alike on its territory. Even if it seeks U.S. assistance against individuals and groups at war with the state, Pakistan is still obliged to ensure that its actions and those of the U.S. comply with the principles, among others, of distinction and proportionality under International Humanitarian Law, and ideally to give independent observers unhindered access to the areas targeted.’

The ICG’s very first recommendation, therefore, is to lift ‘all travel and other restrictions on independent observers, national and foreign, to the targeted areas in FATA.’ In short, it’s not enough to demand that Washington be transparent in the procedures it follows (whatever Obama might say in his advertised speech on Thursday); it’s also vital for observers to be able to witness and report what is happening on the ground in Waziristan (and elsewhere). Here is Madiha Tahir:

‘I do think these stories would look quite different if they were being told by people from the countries in question. It would shift perspective, and it would highlight as well as marginalize different aspects of the issue. As it is, the conversation is had among largely American, largely white, largely male voices, and the only real options for the rest of us are either to enter that conversation by agreeing or disagreeing, or risk irrelevance.

… [T]he intense focus on the government’s narrative lets journalists and the media off-the-hook for not doing the hard work of actually reporting the stories of those on the receiving end of America’s war in Pakistan.’

The vision machine

News this morning from Roger Stahl of a wonderful new resource and site, The vision machine: media, war, peace. I’ve admired Roger’s work for an age, and his Militainment Inc.: war, media and popular culture has been an indispensable source for my own work on military violence in its various forms; you can find his blog here.

But the new, collective project (for which Roger is a co-director) is even more ambitious; the subject obviously speaks directly to my own concerns, but so too does the format – see the last paragraph below.

TheVisionMachine is a scholarly platform for critically engaging the intersection of war, peace, and media. Using a multimedia approach, the site incorporates pod/vodcasts, media analysis, documentary clips, and links to larger bodies of work. The site is operated by a global group of scholars in the fields of International Relations, Media Production, and Communication Studies.

Thematically, TheVisionMachine is comprised of three components. The first is historical, focusing on the dual development of colonial and media empires from early days of the panorama, photography, print media, radio, TV, to today’s Internet (web 2.0), and social media – thus covering the history of and evolution from old to new digital media. The second is theoretical, using classical and critical theory to examine media as the product and instrument of cultural, economic and political struggles, resistance and revolt. The third is practical, using media production such a micro-documentaries, regular pod/vodcasts, and interactive social media to disseminate research, generate interactive debate, and raise public awareness. As one might guess, The Vision Machine takes direct inspiration from Paul Virilio’s book by the same name, though the site is certainly not limited to his style of thought.

TheVisionMachine is…

1. A Multimedia Journal. TheVisionMachine seeks contributions from a range of prominent thinkers, from academics to activists, media producers, military professionals, journalists, public intellectuals, and more. These contributions range from audio/video profile interviews to short-form original pieces of criticism, theory, observational essays, and documentary work. The driving impulse of the site is to provide a venue for airing cutting-edge ideas and exposing work to larger audiences. If you are interested in becoming involved, please contact us here.

2. A Discussion Platform. TheVisionMachine operates as a hub for an ongoing community conversation. The site hosts a social networking function, discussion boards geared around specific topics, and comment clouds for individual exhibits. Subscribers are encouraged not only to partake of the various articles and micro-documentaries featured on the site, but also to contribute to an expanding range of expertise and perspectives.

3. A Media Production Clearing House. One of the ultimate goals of TheVisionMachine is to operate as a media center, a place for creative collaboration and media production. The structure of the site provides opportunities to “crowdsource” material for larger projects. These could range from academic endeavors to the production of documentary films on relevant subjects. TheVisionMachine is partner with the University of Queensland Media Lab, a $180,000 media monitoring and recording facility, one of the first of its kind housed in a non-corporate, non-military institution.

TheVisionMachine is driven by an explicit attempt to rethink and revamp archaic academic practices of knowledge creation and dissemination. The site aims to move from the average global readership of academic articles in the social sciences (which currently stands at 4.5 readers per published journal article!) to actively engaging a wider public through digital new media. TheVisionMachine is designed as a truly interactive multiplatform space where those with an interest in the infotech/war/peace complex can participate in debates through discussion threads, audio/video postings, and micro-documentary production. Thereby, TheVisionMachine aspires to be a rosetta stone to the complex contemporary global media environment, a tool for interfacing a world where satellite, Internet, cell phone, and other recent technologies directly affect questions of war and peace, control and resistance.

If you need to find the site without using the link above, you should note that there are several ‘vision machines’ on the web – but only one is ‘thevisionmachine.com‘. Note, too, that the site takes its title from Paul Virilio‘s book (which is available here) but isn’t limited to his style of thought…

Just looking?

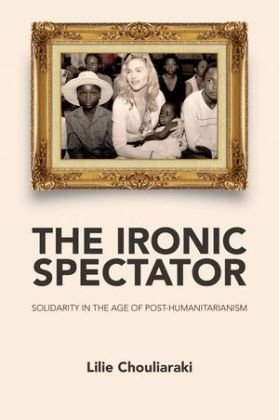

Most readers interested in the politics of humanitarianism and what Eyal Weizman calls ‘the humanitarian present‘ will know Lilie Chouliaraki‘s work, notably The spectatorship of Suffering (Sage, 2006). She has a new book out now, The ironic spectator: solidarity in the age of post-humanitarianism (Polity, 2012/13):

(Polity, 2012/13):

This path-breaking book explores how solidarity towards vulnerable others is performed in our media environment. It argues that stories where famine is described through our own experience of dieting or or where solidarity with Africa translates into wearing a cool armband tell us about much more than the cause that they attempt to communicate. They tell us something about the ways in which we imagine the world outside ourselves.

By showing historical change in Amnesty International and Oxfam appeals, in the Live Aid and Live 8 concerts, in the advocacy of Audrey Hepburn and Angelina Jolie as well as in earthquake news on the BBC, this far-reaching book shows how solidarity has today come to be not about conviction but choice, not vision but lifestyle, not others but ourselves – turning us into the ironic spectators of other people’s suffering.

This intersects with my own interest in the modern and late modern spectatorship of war, though in complex and far from straightforward ways (I have particularly in mind the contemporary ‘consumption’ of war), so I was excited to read this description of Lilie’s current research:

My current work focuses on the mediation of war, where I explore the various public genres through which war has been mundanely communicated in our culture, from photojournalism to films and from memoirs to news. The aim is to better understand how our collective imagination of the battlefield and its sufferings, what we may call our ‘war imaginary’, has been shaping the moral tissue of public life, in the course of the past century (1914-2012).

As part of this project, she has an essay forthcoming in Visual communication later this year, ‘The humanity of war: iconic photojournalism, 1914-2012’, which will also appear in extended form in Nick Couldry, Mirca Madianou and Amit Pinchevski (eds) The Ethics of Media (Palgrave, 2013).

In digestion

We’ve been in Mexico for the last two weeks – hence the silence – so there’s lots to catch up on and with.

We’ve been in Mexico for the last two weeks – hence the silence – so there’s lots to catch up on and with.

While I was away Joanne Sharp wrote with news of her experience with CNN… Reader’s Digest is in trouble, and readers will surely know of Jo’s Condensing the Cold War: Reader’s Digest and American Identity (University of Minnesota Press, 2000). So CNN asked her for a commentary, which you can find here; here’s the conclusion:

Perhaps the decline of Reader’s Digest’s fortunes was inevitable with the longer-term social and political influences of 60s counterculture, the failure of general interest magazines, the rise of global media targeted at specific niches and the advent of the internet. But of equal importance was the end of the Soviet threat: With the fall of its arch enemy, the Evil Empire, there was no mirror against which it could present an alternative image of America and its historic mission.

As Jo ruefully notes, there is an irony in all this (and not only in being asked to condense her Condensing, if you see what I mean): ‘something that was rushed together between 1 and 4am (in Helsinki – I didn’t even have my notes!) – has reached a far larger audience than anything I’ve spent months sweating over.’ But, as she also notes, some of the online comments would provide material for another essay….

‘The largest picture in the world’

I was in Lexington Thursday-Saturday to give the first of this year’s Committee on Social Theory lectures at the University of Kentucky. The theme this year is “Mapping“, and this was the first outing for “Gabriel’s Map: cartography and corpography in modern war”. The video will be posted online in a week or so, and there will also be an online interview with the journal disClosure, which is moving to a digital platform. I was last in Kentucky soon after I moved to UBC, so some time around 1989/90, to give one of the first of these lectures, and this occasion was as enjoyable as the first: many thanks to Jeremy Crampton and his wonderful colleagues and graduate students for such warm hospitality on such a chilly week! That said, being invited to talk about “Mapping” by Jeremy is like being invited to talk about Marxism by David Harvey, so I was relieved everything went so well; I learned much from the questions, comments and conversations, so no doubt the second outing will see a different presentation. Then, somewhere down the line, I’ll translate it into written form.

One of the most enjoyable parts of preparing a presentation, for me anyway, is the image research and design, which invariably takes me to sites and sources I’d never otherwise find. And because it can take an age to find the right image, it slows down the process and gives me time to think more carefully (and I hope creatively) about the argument I’m developing. This was no exception: again and again, as I raided image banks on the First World War, I encountered the work of Australian photographer and film-maker Frank Hurley (1885-1962). In fact, it’s one of his photographs that I cut for the banner of this blog (‘Moving Forward/Supporting troops of the 1st Australian Division walking on a duckboard track near Hooge, in the Ypres Sector’).

When the First World War began Hurley was in Antarctica as the photographer for the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, Ernest Shackleton‘s legendary attempt to reach the South Pole on foot in 1914-1917, which ended in near disaster when the expedition’s support vessel became trapped and was eventually crushed in the pack ice. The First Officer on the ill-fated Endurance described Hurley as ‘a warrior with his camera’ who would ‘go anywhere or do anything to get a picture.’

When the First World War began Hurley was in Antarctica as the photographer for the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, Ernest Shackleton‘s legendary attempt to reach the South Pole on foot in 1914-1917, which ended in near disaster when the expedition’s support vessel became trapped and was eventually crushed in the pack ice. The First Officer on the ill-fated Endurance described Hurley as ‘a warrior with his camera’ who would ‘go anywhere or do anything to get a picture.’

Sure enough, soon after he returned to England Hurley was appointed as one of two official photographers to the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) in July 1917 with the honorary rank of Captain. (War correspondents were expressly forbidden to take photographs, which is why official photographers were appointed – and subject to regulation and censorship). Hurley left England the following month for what he called ‘the grim duties of France’. He was constantly haunted by the horror gouged into the landscape of the front line:

Sure enough, soon after he returned to England Hurley was appointed as one of two official photographers to the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) in July 1917 with the honorary rank of Captain. (War correspondents were expressly forbidden to take photographs, which is why official photographers were appointed – and subject to regulation and censorship). Hurley left England the following month for what he called ‘the grim duties of France’. He was constantly haunted by the horror gouged into the landscape of the front line:

‘After, we climbed to the crest of hill 60, where we had an awesome view over the battlefield to the German lines. What an awful scene of desolation! Everything has been swept away: only stumps of trees stick up here & there & the whole field has the appearance of having been recently ploughed. Hill 60 long delayed our infantry advance, owing to its commanding position & the almost impregnable concrete emplacements & shelters constructed by the Bosch. We eventually won it by tunnelling underground, & then exploding three enormous mines, which practically blew the whole hill away & killed all the enemy on it. It’s the most awful & appalling sight I have ever seen. The exaggerated machinations of hell are here typified. Everywhere the ground is littered with bits of guns, bayonets, shells & men. Way down in one of these mine craters was an awful sight. There lay three hideous, almost skeleton decomposed fragments of corpses of German gunners. Oh the frightfulness of it all… Looking across this vast extent of desolation & horror, it appeared as though some mighty cataclysm had swept it off & blighted the vegetation, then peppered it with millions of lightning stabs. It might be the end of the world where two irresistible forces are slowly wearing each other away.’

Or again:

‘The Menin Rd is one of the, if not the, most ghastly approach on the whole front. Accretions of broken limbers, materials & munitions lay in piles on either side, giving the road the appearance of running through a cutting. Any time of the day it may be shelled & it is absolutely impossible owing to the congested traffic for the Boche to avoid getting a coup with each shell. The Menin road is like passing through the Valley of death, for one never knows when a shell will lob in front of him. It is the most gruesome shambles I have ever seen…’

But throughout his diary he is also evidently entranced, even thrilled by the aesthetic effect of such spectacular violence:

‘The battlefield in the night was a wonderful sight of star shells & flashes. The whole sky seemed a crescent of shimmering sheet lightning like illumination. It was all very beautiful yet awesome and terrible.’

At Ypres, he confesses that the shattered town is now ‘aesthetically … far more interesting than the Ypres that was’. Making his way along the Menin Road at twilight:

At Ypres, he confesses that the shattered town is now ‘aesthetically … far more interesting than the Ypres that was’. Making his way along the Menin Road at twilight:

‘No sight could be more impressive than walking along this infamous shell swept road, to the chorus of the deep bass booming of the drum fire, & the screaming shriek of thousands of shells. It was great, stupendous & awesome.’

Later:

‘The shells shrieked in an ecstasy overhead, & the deep boom of artillery sounded like a triumphant drum roll. Those murderous weapons the machine guns maintained their endless clatter, as if a million hands were encoring & applauding the brilliant victory of our countrymen. It was ineffably grand & terrible…’

Above all, Hurley was tormented by the difficulty of conveying the full extent of what he saw in a single exposure. In his diary he confided that

‘We have even a worse time than the infantry, for to get pictures one must go into the hottest & even then come out disappointed. To get War pictures of striking interest & sensation is like attempting the impossible.’

He later explained:

‘None but those who have endeavoured can realise the insurmountable difficulties of portraying a modern battle by the camera. To include the event on a single negative, I have tried and tried, but the results are hopeless. Everything is on such a vast scale. Figures are scattered — the atmosphere is dense with haze and smoke — shells will not burst where required — yet the whole elements of a picture are there could they but be brought together and condensed.’

Hurley passionately believed that it was only by the superimposition of different negatives to form a single, ‘condensed’ image that he could re-present the violence of war – and, I think, its shocking, thrilling aesthetic. Towards the end of September 1917 Hurley recorded

‘a great argument with Bean about combination pictures. Am thoroughly convinced that it is impossible to secure effects – without resorting to composite pictures.’

Charles Bean was Australia’s Official War Correspondent (more here, and for the documentary-drama, Charles Bean’s Great War, see here), and he was equally adamant that Hurley’s method was itself so violent that it destroyed the truth: to Bean, Hurley’s montages were ‘little short of fake’ and violated the imperative to view photographs as ‘sacred records’ of the war. Indeed, Bean insisted that ‘press photography in this war is such a construction of flimsy fake,’ and ‘that is the last thing a historian wants to build on.’ In October Bean presented an ultimatum to which Hurley responded in a characteristically uncompromising fashion:

Charles Bean was Australia’s Official War Correspondent (more here, and for the documentary-drama, Charles Bean’s Great War, see here), and he was equally adamant that Hurley’s method was itself so violent that it destroyed the truth: to Bean, Hurley’s montages were ‘little short of fake’ and violated the imperative to view photographs as ‘sacred records’ of the war. Indeed, Bean insisted that ‘press photography in this war is such a construction of flimsy fake,’ and ‘that is the last thing a historian wants to build on.’ In October Bean presented an ultimatum to which Hurley responded in a characteristically uncompromising fashion:

‘Had a lengthy discussion with Bean re pictures for Exhibition & publicity purposes. Our Authorities here will not permit me to pose any pictures or indulge in any original means to secure them. They will not allow composite printing of any description, even though such be accurately titled nor will they permit clouds to be inserted in a picture. As this absolutely takes all possibilities of producing pictures from me, I have decided to tender my resignation at once. I conscientiously consider it but right to illustrate to the public the things our fellows do & how war is conducted. These can only be got by printing a result from a number of negatives or reenactment. This is out of reason & they prefer to let all these interesting episodes pass. This is unfair to our boys & I conscientiously could not undertake to continue the work.’

The next morning Hurley resigned:

‘I sent in my resignation this morning & await the result of igniting the fuse. It is disheartening, after striving to secure the impossible & running all hazards to meet with little encouragement. I am unwilling & will not make a display of war pictures unless the military people see their way clear to give me a free hand. Canada has made a great advertisement out of their pictures & I must beat them.’

According to Robert Dixon’s engaging essay ‘Travelling Mass-Media Circus: Frank Hurley and Colonial Modernity’, Hurley had Canada in his sights because the Canadian War Records Office had staged a highly successful photographic exhibition at the Grafton Galleries in London the previous December, which had included vast enlargements using multiple negatives; the follow-up exhibition in July had as its centrepiece what was advertised as ‘the largest photograph in the world’, ‘Dreadnoughts of the Battlefield’, which occupied an entire wall of the gallery.

Within days a compromise of sorts had been reached: Hurley was allowed to make six ‘combination enlargements’ for his public exhibition, provided they were clearly labelled as composites, and he withdrew his resignation. (For more on the spat between Hurley and Bean, and the vexed political-epistemological issues at stake, see here).

But it was not until May 1918 – after he had completed a photographic expedition to record Australian troops fighting in Palestine – that Hurley was able to prepare his photographs for the London exhibition (the catalogue for the later show in Sydney is here). He was particularly excited by two montages. The first, ‘DEATH THE REAPER” was made up of two negatives: ‘One, the foreground, shows the mud-splashed corpse of a Boche floating in a shell crater. The second is an extraordinary shell burst: the form of which resembles death.’

What is striking about Hurley’s gloss – and the composition of the image itself – is the evident striving for a particular aesthetic effect: the compulsion to ‘secure effects’ (above) that were also affects. Hurley reserved his most extravagant self-praise for a second photo-work which was made from 12 separate negatives:

‘Our largest picture, “THE RAID”, depicting an episode an the Battle of Zonneke [south-west of Passchendaele] measures over 20 ft. x 15’6″ high. Two waves of infantry are leaving the trenches in the thick of a Boche Barrage of shells and shrapnel. A flight of Bombing Aeroplanes accompanies them. An enemy plane is burning in the background. The whole picture is realistic of battle, the atmospheric effects of battle smoke are particularly fine.’

You can see an animation of the composition process here and a video here, and although Hurley claims this as a ‘realistic’ photo-work, the process of composition is, again, an artfully studied one that was plainly intended to produce a particular aesthetic – and cinematic – effect.

Even more than this, though, Hurley was – as Julian Thomas makes very clear here, a show man: Robert Dixon argues that by the 1920s ‘Hurley had become not only the ring-master but also the main attraction in his own travelling, international, multi- and mass-media circus.’ (Given how much I enjoy devising my own presentations, perhaps that’s also why I find the man so interesting….).

And ‘The Raid’, sometimes also called ‘Over the top’ (shown leaning against a wall in London, left) was his bid to produce ‘the largest picture in the world’ (a quest which shows no sign of coming to an end).

You can find online galleries of Hurley’s photographs from the First World War here. I used several of them in my presentation at Lexington, and so this excursion into Hurley’s war work is not a side-track: I also used passages from several novels (clearly noted as such), partly to trouble the simple distinctions between ‘fiction’ and ‘non-fiction’ and to draw attention to the constructedness of our histories, but partly too because there are some truths (sic) that can be conveyed most effectively through the imaginative resources of the novel. In the case of Tom McCarthy’s luminous novel C, which I’ve invoked before, there are complex relationships between the documentary record and the fictional narrative: C is clearly a work of prodigious imagination, but just as clearly saturated in archival research. I’m left wondering what a latter-day Hurley would have made of it – and whether photographs are still subject to more stringent protocols than texts as a result of a presumptive indexicality. What now counts as ‘fakery’ once Bean’s ‘sacred records’ have become secularised?

StateTube

An update to my post on social media and late modern war (also here): Rebecca Stein writes with the excellent news that she has published an extended version of her MERIP commentary on Israel’s Twitter-war on Gaza: “StateTube: Anthropological reflections on social media and the Israeli state”, in Anthropological Quarterly 85 (3) (2012) 893-916. The essay complicates what she calls the usual narrative about digital militancy (which is the theme of a special section of the journal): ‘the notion of new technologies that organically liberate from below, and of states invested chiefly in their repression from above.’

That said, some Israelis seem to have an astonishingly obdurate view of the power of social media – Rebecca quotes one member of Likud claiming that “Facebook pages … have as much impact as a tank – and sometimes even more” – and, as she notes, remarkably little sense of the countervailing possibilities.

All of which makes me wonder about a sequel to David Fincher‘s film about Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, The social network (2010): in the light of Rebecca’s ethnographic work, the original poster (reproduced above) suggests an altogether different scenario….