Next month Cambridge University Press is publishing a book of essays edited by Peter Bergen and Daniel Rothenberg, Drone wars: transforming conflict, law and policy, due out from Cambridge University Press at the end of the year. Here’s the blurb:

Next month Cambridge University Press is publishing a book of essays edited by Peter Bergen and Daniel Rothenberg, Drone wars: transforming conflict, law and policy, due out from Cambridge University Press at the end of the year. Here’s the blurb:

Drones are the iconic military technology of many of today’s most pressing conflicts, a lens through which U.S. foreign policy is understood, and a means for discussing key issues regarding the laws of war and the changing nature of global politics. Drones have captured the public imagination, partly because they project lethal force in a manner that challenges accepted rules, norms, and moral understandings. Drone Wars presents a series of essays by legal scholars, journalists, government officials, military analysts, social scientists, and foreign policy experts. It addresses drones’ impact on the ground, how their use adheres to and challenges the laws of war, their relationship to complex policy challenges, and the ways they help us understand the future of war. The book is a diverse and comprehensive interdisciplinary perspective on drones that covers important debates on targeted killing and civilian casualties, presents key data on drone deployment, and offers new ideas on their historical development, significance, and impact on law and policy. Drone Wars documents the current state of the field at an important moment in history when new military technologies are transforming how war is practiced by the United States and, increasingly, by other states and by non-state actors around the world.

And here is the Contents List:

Part I. Drones on the Ground:

1. My guards absolutely feared drones: reflections on being held captive for seven months by the Taliban David Rohde

2. The decade of the drone: analyzing CIA drone attacks, casualties, and policy Peter Bergen and Jennifer Rowland

3. Just trust us: the need to know more about the civilian impact of US drone strikes Sarah Holewinski

4. The boundaries of war?: Assessing the impact of drone strikes in Yemen Christopher Swift

5. What do Pakistanis really think about drones? Saba ImtiazPart II. Drones and the Laws of War:

6. It is war at a very intimate level USAF pilot

7. This is not war by machine Charles Blanchard

8. Regulating drones: are targeted killings by drones outside traditional battlefields legal? William Banks

9. A move within the shadows: will JSOC’s control of drones improve policy? Naureen Shah

10. Defending the drones: Harold Koh and the evolution of US policy Tara McKelvey

Part III. Drones and Policy Challenges:

11. ‘Bring on the magic’: using drones in combat Michael Waltz

12. The five deadly flaws of talking about emerging military technologies and the need for new approaches to law, ethics, and war P. W. Singer

13. Drones and cognitive dissonance Rosa Brooks

14. Predator effect: a phenomenon unique to the war on terror Meg Braun

15. Disciplining drone strikes: just war in the context of counterterrorism David True

16. World of drones: the global proliferation of drone technology Peter Bergen and Jennifer RowlandPart IV. Drones and the Future of Warfare:

17. No one feels safe Adam Khan

18. ‘Drones’ now and what to expect over the next ten years Werner Dahm

19. From Orville Wright to September 11: what the history of drone technology says about the future Konstantin Kakaes

20. Drones and the dilemma of modern warfare Richard Pildes and Samuel Issacharoff

21. How to manage drones, transformative technologies, the evolving nature of conflict and the inadequacy of current systems of law Brad Allenby

22. Drones and the emergence of data-driven warfare Daniel Rothenberg

Over at Foreign Policy you can find an early version of Chapter 6, which is an interview with a drone pilot conducted by Daniel Rothenberg. There are two passages in the interview that reinforce the sense of the bifurcated world inhabited by drone crews that I described in ‘From a view to a kill’ and ‘Drone geographies’ (DOWNLOADS tab). On the one side the pilot confirms the inculcation of an intimacy with ground troops, particularly when the platforms are tasked to provide Close Air Support, which is in some degree both reciprocal and verbal:

“Because of the length of time that you’re over any certain area you’re able to engage in lengthy communications with individuals on the ground. You build relationships. Things are a little more personal in an RPA than in an aircraft that’s up for just a few hours. When you’re talking to that twenty year old with the rifle for twenty-plus hours at a time, maybe for weeks, you build a relationship. And with that, there’s an emotional attachment to those individuals.

“You see them on a screen. That can only happen because of the amount of time you’re on station. I have a buddy who was actually able to make contact with his son’s friend over in the AOR [area of responsibility]. If you don’t think that’s going to make you focus, then I don’t know what will.

“Many individuals that have been over there have said, ‘You know, we were really happy to see you show up’; ‘We knew that you were going to keep us from being flanked’; ‘We felt confident in our ability to move this convoy from ‘A’ to ‘B’ because you were there.’ The guy on the ground and the woman on the ground see how effective we are. And it gives them more confidence.”

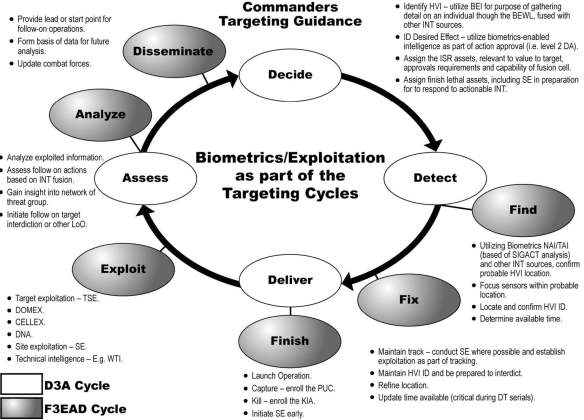

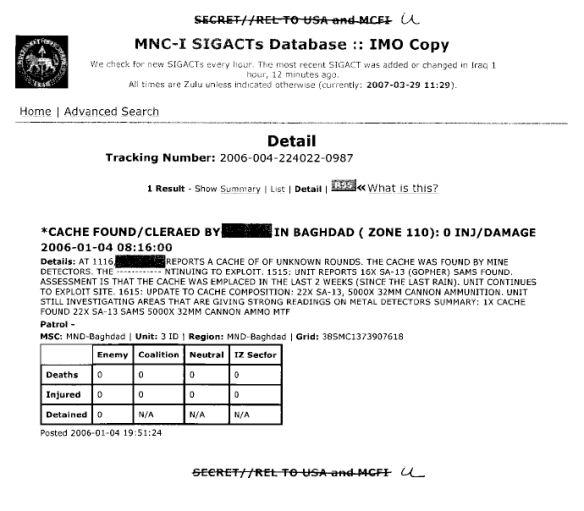

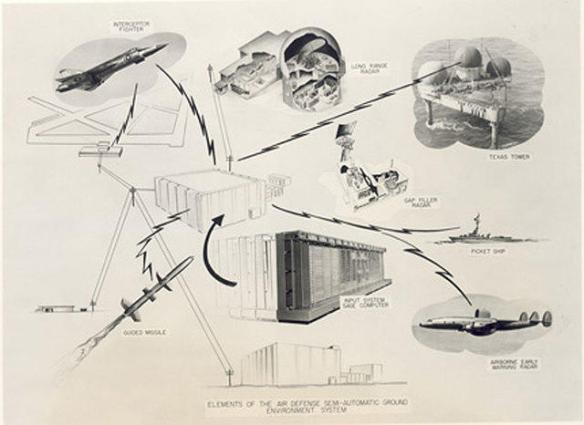

[The image above is taken from my ‘Angry Eyes’ presentation; the Predator pilot in this instance was involved in orchestrating the air strike in Uruzgan province, Afghanistan on 21 February 2010, and the quotation is taken from the US Army investigation into the incident. I’m converting the presentation into the final chapter for The everywhere war, and I’ll post the draft as soon as I’m finished.]

But when the pilot in Rothenberg’s interview goes on to claim that ‘Targeting with RPAs is very intimate’ and that ‘It is war at a very intimate level’, he reveals on the other side an altogether different sense of intimacy: one that is strictly one-sided, limited to the visual, and which resides in a more abstracted view:

“Flying an RPA, you start to understand people in other countries based on their day-to-day patterns of life. A person wakes up, they do this, they greet their friends this way, etc. You become immersed in their life. You feel like you’re a part of what they’re doing every single day. So, even if you’re not emotionally engaged with those individuals, you become a little bit attached. I’ve learned about Afghan culture this way. You see their interactions. You’re studying them. You see everything.”

The distinction isn’t elaborated, but the claims of ‘immersion’ and becoming ‘part of what they’re doing every day’ are simply astonishing, no? You can find more on the voyeurism of ‘pattern of life analysis’ and the remarkable conceit that ‘you see everything’ here.

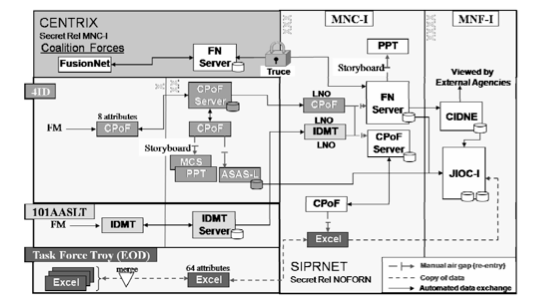

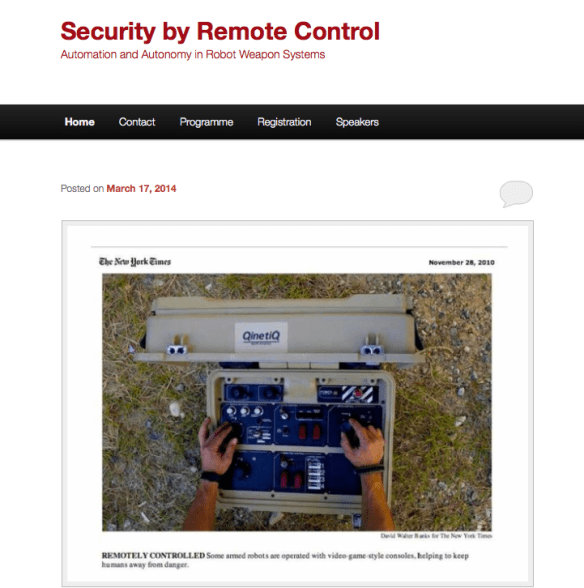

[The image above is taken from my ‘Drone geographies’ presentation]

The interview emphasises a different bifurcation, which revolves around the alternation between ‘work’ and ‘home’ when remote operations are conducted from the United States:

“”When you’re doing RPA operations, you’re mentally there, wherever there is. You’re flying the mission. You’re talking to folks on the ground. You’re involved in kinetic strikes. Then you step out the ground control station (GCS) and you’re not there anymore…

“Those are two very, very different worlds. And you’re in and out of those worlds daily. I have to combine those two worlds. Every single day. Multiple times a day. So, I am there and then I am not there and then I am there again. The time between leaving the GCS [Ground Control Station] and, say, having lunch with my wife could be as little as ten minutes. It’s really that fast.”

You can find much more on these bifurcations in my detailed commentary on Grégoire Chamayou‘s Théorie du drone here and in ‘Drone geographies’ (DOWNLOADS tab).

There’s one final point to sharpen. In my developing work on militarized vision, and especially the ‘Angry eyes’ presentation/essay, I’ve tried to widen the focus beyond the strikes carried out by Predators and Reapers to address the role they play in networked operations where the strikes are carried out by conventional strike aircraft. Here is what Rothenberg’s pilot says about what I’ve called the administration of military violence (where, as David Nally taught me an age ago, ‘administration’ has an appropriately double meaning):

‘”Flying an RPA is more like being a manager than flying a traditional manned aircraft, where a lot of times your focus is on keeping the shiny side up; keeping the wings level, putting the aircraft where it needs to be to accomplish the mission. In the RPA world, you’re managing multiple assets and you’re involved with the other platforms using the information coming off of your aircraft.

“You could use the term ‘orchestrating’; you are helping to orchestrate an operation.”

***

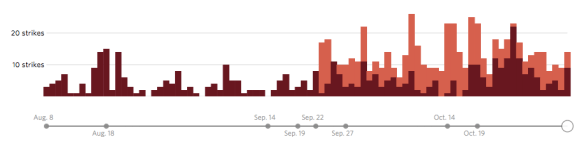

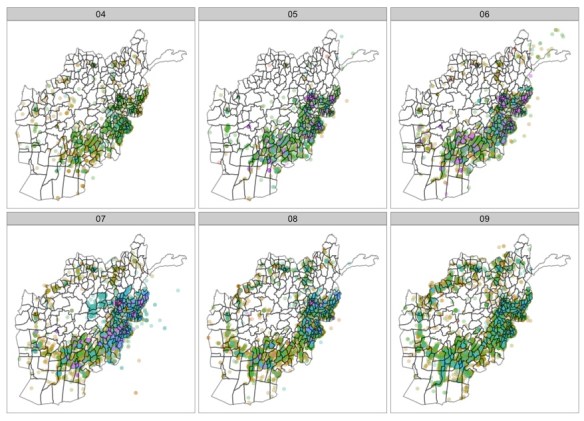

Drone wars appears just as remote operations over Iraq and Syria are ramping up: you can find an excellent review by Chris Cole at Drone Wars UK here, ‘Drones in Iraq and Syria: What we know and what we don’t.’ The images below are from the Wall Street Journal‘s interactive showing all air strikes reported by US Central Command 8 August through 3 November 2014:

During this period 769 coalition air strikes were reported: 434 in Syria (the dark columns), including 217 on the besieged border city of Kobane, and 335 in Iraq (the light columns), including 157 on Mosul and the Mosul Dam.

But bear in mind these figures are for all air strikes and do not distinguish between those carried out directly by drones and those carried out by conventional strike aircraft. As Chris emphasises:

‘Since the start of the bombing campaign, US drones have undertaken both surveillance and strike missions in Iraq and Syria but military spokespeople have refused to give details about which aircraft are undertaking which strikes repeatedly using the formula “US military forces used attack, fighter, bomber and remotely-piloted aircraft to conduct airstrikes.”’

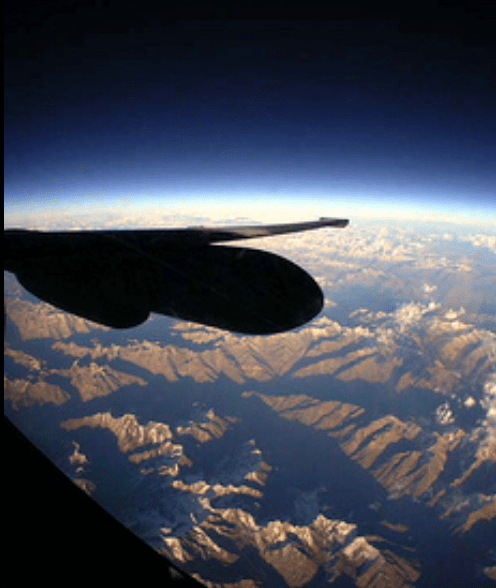

Although the USAF has used a mix of MQ-1 (Predator) and MQ-9 (Reaper) drones, F-15E, F-16, F/A-18 and F-22 fighters, B-1 bombers, AC-130 gunships and AH-64 Apache helicopters in these operations, it seems likely that its capacity to use remote platforms to provide intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance is limited by its continuing commitments in Afghanistan (though Britain’s Royal Air Force has now deployed its Reapers for operations in both Iraq and Syria).

IS (Islamic State) claims to have its own drones too. In February it released video of its aerial surveillance of Fallujah in Iraq, taken from a DJI Phantom FC40 quadcopter, in August it released video of Taqba air base in Syria taken from the same platform, tagged as ‘a drone of the Islamic State army’, and in September a propaganda video featuring hostage John Cantile showed similar footage of Kobane (below).

These image streams are all from commercial surveillance drones, but in September the Iranian news agency Fars reported that Hezbollah had launched an air strike from Lebanon against a command centre of the al-Nursra Front outside Arsal in Syria using an armed (obviously Iranian) drone.

You can find Peter Bergen’s and Emily Schneider‘s view on those developments here, and a recent survey of the proliferation of drone technologies among non-state actors here.

The details of both the state and non-state air strikes remain murky, but I doubt that much ‘intimacy’ is claimed for any of them.