I’ve had my head down these past few weeks writing the long-form version of ‘Little Boys and Blue Skies’ (see here and here for preliminary notes), and en route I’ve been doing some more digging into the entanglements between nuclear weapons and drones. And, as you’ll see, I ended up in Korea.

Until now I’ve focused on the US Air Force‘s use of B-17 drones flown by remote control from ground stations and accompanying director aircraft to sample the atomic clouds produced by tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands from 1946, and its Project Brass Ring in the early 1950s designed to convert a B-47 Stratojet into a similarly remotely operated carrier capable of delivering the next generation of thermonuclear (hydrogen) bombs.

But the US Navy was no bystander.

In fact, the first series of postwar atomic tests, Operation Crossroads in July 1946, was an attempt by the Navy to move centre stage after Hiroshima and Nagasaki – when the Air Force had played the leading role – and to establish that sea power was still relevant in the atomic age. The target for the bombs was a fleet of 95 ships (ironically readied at Pearl Harbor) and now anchored in the Bikini lagoon. But critics inside and outside Congress doubted the value of the tests: the bombs would be of the same type as ‘Fat Man’, dropped over Nagasaki, so no development in weapons technology was involved, and in any event surface ships were unlikely to be the targets of such devastating weapons. They dismissed Crossroads as an expensive, purely theatrical extravaganza. And certainly, despite the remote location, 4,000 miles from San Francisco, every effort was made to attract international attention, both public and professional; the official record trumpeted that ‘never before had a nation fanfared its most secret weapon so closely before the eyes of the world’ [the official ‘pictorial record’ is here].

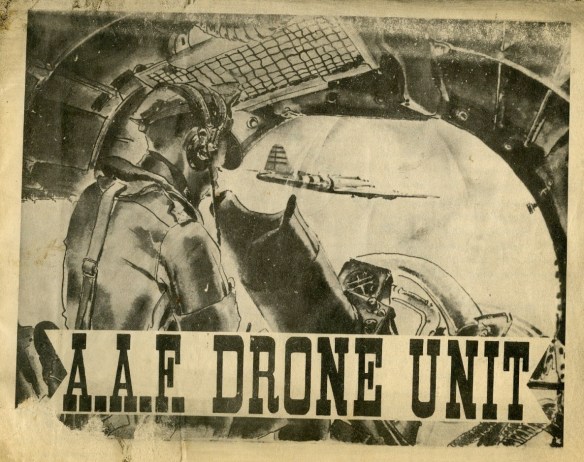

As far as the Air Force was concerned, however, Crossroads would be ‘a laboratory test’ not a ‘bomb-versus-battleship stunt’ [Sidney Shalett, ‘Atomic bomb test no “stunt” to AAF’, New York Times, 21 February 1946]. It would involve not only bomb delivery by one of its bombers but also cloud monitoring by drones. ‘Almost as dramatic as the flight of the B-29 bomber’, General W.E. Kepner told reporters, ‘will be the plunge of the unpiloted but mothered drone planes into the sky-reaching, irradiated cloud.’ ‘Where men cannot go,’ he added, ‘the drone will take electronic and other recording instruments.’ Vice-Admiral William Blaney told reporters that ‘robot aircraft will dive into the atomic blast to gather scientific data’ and ‘uncover facts of radioactive phenomena as well as supply data on blast effects on airborne aircraft.’

As I noted in my earlier post, both the Air Force and the Navy supplied the drones.

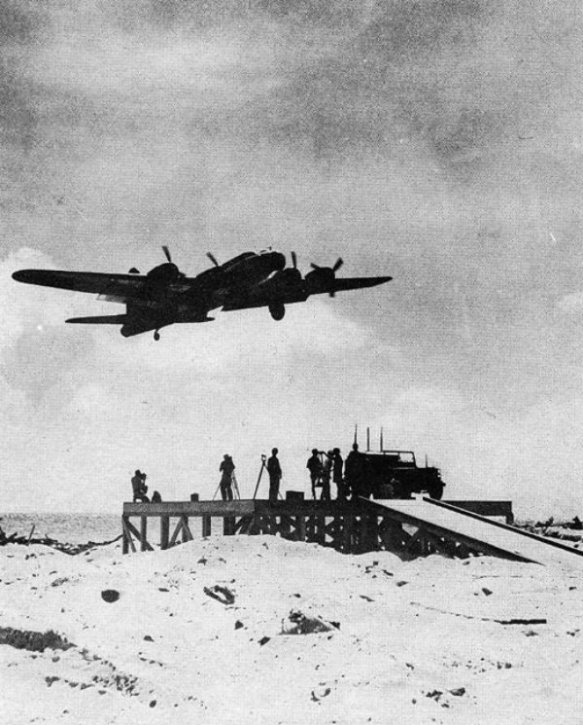

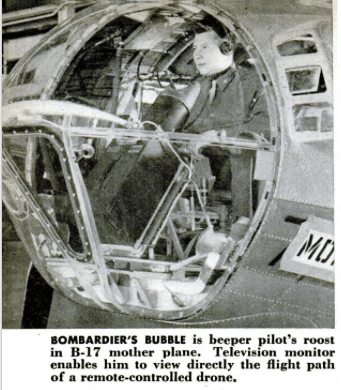

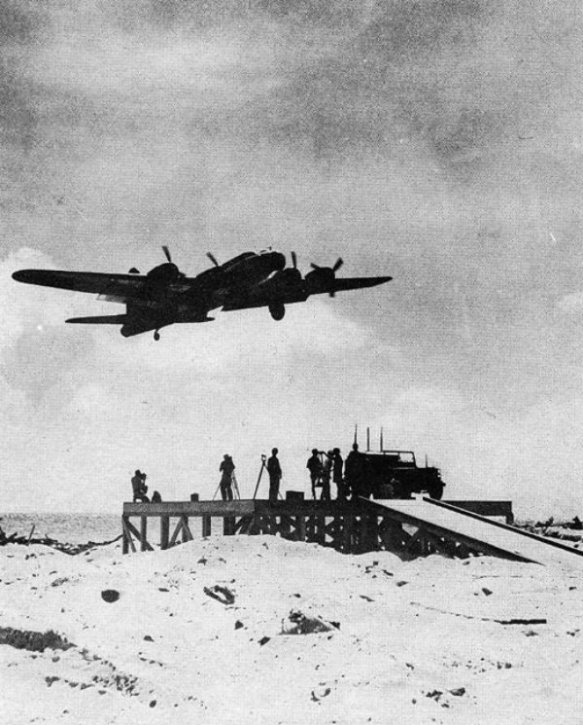

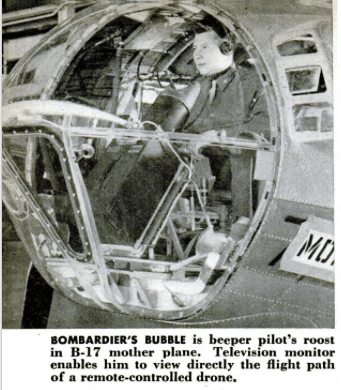

For its part, the Air Force retained its love affair with the heavy bombers that had driven its ill-fated Project Aphrodite in the dog days of the war, in which war-weary B-17 Flying Fortresses were filled with high explosives and flown from an accompanying director aircraft into enemy targets in Occupied Europe. This time its Drones Unit utilised new B-17s: four were converted into drones operated by radio-control from four others flying at a safe distance, while one acted as the master control aircraft. The drones were stripped of all their defensive armaments and fitted with radio and television equipment; air filters were fixed to their top turrets to trap particles from the cloud and collection bags installed in their bomb bays. Ground controllers launched the drones from control jeeps and then handed off to the airborne controllers (‘beeper pilots’) on board the accompanying B-17s who directed the aircraft into the cloud before returning them to the ground controllers who managed the landing.

But the Navy had experimented with its smaller, carrier-based aircraft during the war too. Its Project Option had used TDR-1 drones loaded with 500-2000 lb bombs with nose-mounted TV cameras controlled from the back seat of an Avenger Torpedo bomber.

As it happens, one of the first missions of the Special Task Air Group (STAG-1) had been to deploy its drones in support of a US assault on the Marshall Islands, but the Marines landed long before the planned invasion date; the Group was then tasked with attacking targets of opportunity throughout the Solomon Islands. In a single month, between 27 September and 26 October 1944, STAG-1 launched 46 drones, of which 29 successfully destroyed their targets. This was a short-lived project in another sense. As with Aphrodite, these were all in effect kamikaze missions in which the unoccupied aircraft plunged into its targets and exploded: James Hall provides a pilot’s view in his American Kamikaze, and you can find an exquisite analysis of the project in the second chapter of Katherine Chandler‘s thesis, Drone flight and failure: the United States’ secret trials, experiments and operations in unmanning, 1936-1973. For Crossroads, less than two years later, the Navy used carrier-based Grumman F6F-5 Hellcat fighter aircraft as drones and as control aircraft, mustering 30 drones and 26 control aircraft (below, the USS Shangri-La en route to Bikini with the drones on the flight deck).

The first shot in the series, codenamed Able, took place on 1 July 1946. At 0900 Dave’s Dream dropped the bomb over the target fleet, but the result was not the thrilling spectacle that had been advertised [below: Able shot from Enyu Island]. Visually it was a damp squib. Judged by its own Broadway razzamatazz, one reporter jibed, it was a complete flop: ‘Operation Chloroform, the logical sequel to Operation Build-Up and Handout.’

Scientifically it was not much better. Although Vice-Admiral Blaney initially declared that the bomb was dropped ‘with very good accuracy’, in fact it detonated off-target, exploding over one of the instrumentation vessels and compromising the readings from many others. Even most of the high-speed cameras missed the shot. One critic concluded that ‘from the standpoint of pure science no test was ever more haphazard’ [more in Jonathan Weisgall, Operation Crossroads: the atomic tests at Bikini Atoll (1994) and Keith Parsons and Robert Zabella, Bombing the Marshall islands:a Cold War tragedy (2017)].

Against this catalogue of errors, which was glossed over in the official report, the aerial sampling missions were judged a considerable success.

(When the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty put an end to atmospheric testing in 1963 you might think the need for aerial sampling disappeared with the cloud. But the US still operates two sampling aircraft as the ‘Constant Phoenix’ program that acts as a supplement to the satellite sensor network of the US Atomic Energy Detection System: earlier this year Constant Phoenix flew sampling missions to assess North Korea’s claim to have detonated a hydrogen bomb).

Back to the future. As soon as the bomb was released over Bikini the first B-17 control aircraft turned its huge drone (Fox) into the cloud at an altitude of 24,000 feet; Fox was then switched to its automatic pilot, entering the cloud eight minutes after the explosion, while the control (or “beeper”) aircraft raced around the cloud and resumed control when the drone emerged on the other side. Fox was followed by George (at 30,000 feet), How (at 18,000 feet) and Love (at 12,000 feet). All four drones were directed back to Eniwetok atoll where they were handed back to the ground controllers in jeeps at the end of the runway who taxied them to the radiological safe area where the filters and bags were removed and flown to Los Alamos Laboratory for analysis (below).

The Navy launched four of its drones from the Shangri-La, but only three of them – Yellow, White and Blue – sampled the cloud at 5,000, 10,000 and 15,000 feet before being directed back to Roi island for a ground landing and sample recovery (below).

The official report emphasised that this was a notable first. ‘At Hiroshima and Nagasaki,’ it declared, ‘a few photographs and pressure measurements were made of the explosions, but almost nothing of value to physicists was learned.’ Crossroads had changed that; ‘for the first time samples had been taken from an atomic cloud’ during what one military engineer hailed as ‘the most hugely instrumented experiment in history’.

To the Air Force its drones had made crucial contributions not only to the aerial sampling programme but also to the development of remote operations more generally: ‘For the first time, four-motored drone aircraft had been flown without a safety pilot aboard.’ The author of the official report was equally impressed. ‘With no one aboard,’ he marvelled, ‘these great planes were radio-guided through their prescribed flights across the target area, a unique and impressive feat.’ In a footnote he continued:

To the Air Force its drones had made crucial contributions not only to the aerial sampling programme but also to the development of remote operations more generally: ‘For the first time, four-motored drone aircraft had been flown without a safety pilot aboard.’ The author of the official report was equally impressed. ‘With no one aboard,’ he marvelled, ‘these great planes were radio-guided through their prescribed flights across the target area, a unique and impressive feat.’ In a footnote he continued:

‘A number of Army Air Forces officials believe that the drone-plane program undertaken for Crossroads advanced the science of drone-plane operations by a year or more… Operation Crossroads was the first operation in which take-off, flight, and landing were accomplished with no one aboard. The feat was an impressive one; many experts had thought it could never be accomplished with planes of this size.’

These were the experiments that captured the imagination of Hanson Baldwin, a military affairs correspondent for the New York Times and Life magazine. He had already predicted that ‘robot planes, rockets, television and radar bombing and atomic bombs will do the work today done by fleets of thousands of piloted bombers.’ Now he saw the future materialising in front of him. ‘Today,’ he wrote in the New York Times for 25 August 1946, ‘planes without crews can be flown from almost anywhere, and can even survive… the atomic cloud.’ At Bikini the drones were controlled over a distance of eight miles or less, but Baldwin had been told that remote control up to fifty and perhaps even 100 miles was possible. These were what today would be called line-of-sight operations, so their range was limited and Baldwin stressed that ‘an unmanned drone cannot be sent careening into a target in Europe by an operator standing at his “beep box” on La Guardia field in New York’. But he was also adamant that a threshold had been crossed:

‘In the Pacific so much experience in the handling of drones was accumulated during the summer and the operations were so far in advance of drone operations during the war that it is safe to say that a simplified and reliable system of drone control – with all that implies – has been achieved…. Drones thus add a new and dangerous instrument to the growing armory of Mars, increase the power of the offensive and further complicate the tasks of the defensive’ [Hanson W. Baldwin, ‘The “Drone”: portent of a push-button war’, New York Times, 25 August 1946].

He was right, and the lines of descent from these post-war experiments to today’s remote operations by the US Air Force reveal continuing entanglements with nuclear weapons.

The official report of Crossroads makes no mention of the implications for remote operations of the smaller Navy drones. Yet the Navy retained an interest in their development, and here too the connections with weapons of mass destruction are more than marginalia.

In April 1952 Herbert Johansen, an associate editor for Popular Mechanics, was invited to observe a flight of four F6F-5K Hellcats – though ‘they could just as well be our fastest jets’ – converted to drone operations at the Navy’s Pilotless Aircraft Laboratory and controlled from a single aircraft off the Atlantic coast. Although the caption to a photograph noted that ‘Big Fellows’ – the Air Force’s Flying Fortresses – ‘can also be radio-controlled’ (see right), it was the smaller drones that got this reporter’s attention.

In April 1952 Herbert Johansen, an associate editor for Popular Mechanics, was invited to observe a flight of four F6F-5K Hellcats – though ‘they could just as well be our fastest jets’ – converted to drone operations at the Navy’s Pilotless Aircraft Laboratory and controlled from a single aircraft off the Atlantic coast. Although the caption to a photograph noted that ‘Big Fellows’ – the Air Force’s Flying Fortresses – ‘can also be radio-controlled’ (see right), it was the smaller drones that got this reporter’s attention.

The Navy was ‘tight-lipped’ about its plans for the Hellcat drones, but Johansen had no difficulty imagining a future in which they would ‘carry atomic warheads and crash-dive as projectiles of destruction’ [‘No Live Operator Aboard’, Popular Mechanics 160 (4) (1952)].

Perhaps this was Johansen’s own, wild conjecture; perhaps not. Bruce Cumings has shown that Washington had contemplated the use of nuclear weapons ‘from the first days of the Korean war’. General MacArthur had requested atomic bombs to support ground operations as early as July 1950; in November President Truman, in response to a reporter’s question, insisted that their use was on the table, and Strategic Air Command was told that aircraft despatched to the Pacific theatre (based on Guam and Okinawa) should have ‘atomic capabilities’. Cumings argues that ‘the US came closest to using nuclear weapons’ in April 1951, when the Pentagon prepared for immediate ‘atomic retaliation’ against any Chinese or Russian escalation; nine Mark IV bombs were transferred to the Air Force, and the President authorised their use against North Korean and Chinese targets. But these were enormous bombs destined for the Air Force’s B-29s – each weighed 11,000 lbs and was far beyond the capacity of the Navy’s Hellcats (though not its AJ-1 bombers) – and they were never used. Still, the Pentagon continued to consider the nuclear option, and in September and October 1951 flights of B-29s carried out simulated runs over the North, dropping dummy atomic bombs to assess their utility as battlefield weapons [see Bruce Cumings, ‘On the strategy and morality of American policy in Korea, 1950 to the present’, Social Science Japan Journal 1 (1) (1998) 57-70; see also here; Daniel Calingaert, ‘Nuclear weapons and the Korean War’, Journal of strategic studies 11 (2) (1988) 177-202; and here).

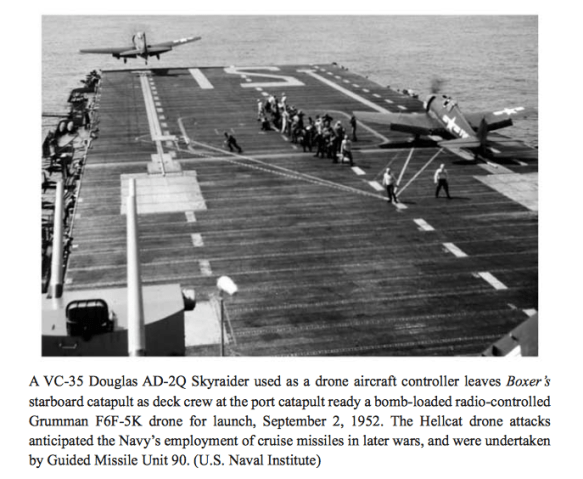

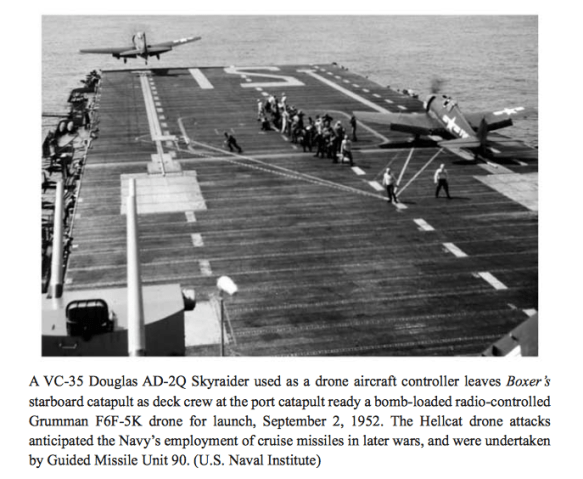

One year later the same bleak prospect as Johansen’s was conjured up by a naval officer much closer to the conflict, who was overseeing an experimental flight of Navy drones against targets in North Korea. Between 28 August and 2 September six Hellcat drones on the carrier USS Boxer were loaded with 2000 lb bombs and, with TV pods slung under their wings, yoked to director aircraft – AD-2Q Skyraiders this time – whose pilots used TV screens to guide what were now described as ‘robot missiles’ on to their targets.

The test roared on to the front pages. An American correspondent cabled a vivid description of what he called ‘one of the most dramatic and historical events of the Korean War’:

‘We watched a guided missile roar off a catapult, climb north-westward in a sweeping turn and head for a dangerous flak-ridden communist target in North Korea more than 150 miles away.

‘As the doomed craft streaked towards its target, grim-faced electronic experts, in a secret room on this ship, rode with the missile, mile by mile, through wondrous electronic instruments. On their dials in the secret room, the experts crossed the Sea of Japan and watched the jagged peaks of Eastern Korea loom in the distance and grow larger. Far from the missile, an automatic device transmitted every dying moment of the missile’s last hour to the USS Boxer.

‘The target – an enemy concentration in a valley between two shadowy hills – was indicated on the receiving instrument – a real flak-ridden trap for any hapless Allied pilot.

‘A second to go now – the signal of the instruments grew stronger as the guided missile dived straight at the target at hundreds of miles an hour. Then the instruments went suddenly blank. The screaming dive had ended squarely on the target and the missile had crashed to oblivion’ [His dispatch was dated 1 September but delayed and censored; it was published in several regional newspapers in the United States and in the Australian press almost three weeks later: ‘United States ready for push-button warfare’, Canberra Times, 19 September 1952].

With that blank screen, he continued, those on board the Boxer knew that ‘here at last in actual combat, was a new era of battle’, when ‘electronic brains will ride in tough, dangerous places, saving the lives of American pilots.’ Or, as one observing officer marvelled, ‘It’s a nice way to fight a war’ [More from Jeremy Hsu, ‘When US Navy suicide drones went to war’, here].

Although observers were ‘amazed at the drone’s sensitive response to remote control’ and the TV screen supposedly ‘enabled the controlling officer to keep the drone “on the target” until the last second, giving the missile unbelievable accuracy’, only one of the six hit its target [‘Navy uses robot missiles against targets in Korea’, New York Times, 18 September 1952]. The others recorded near-misses, but this was enough for Lt-Cdr Lawrence Kurtz, the (less than tight-lipped) commander of Guided Missile Unit 90 responsible for the trial, to boast that the United States had enough of them to ‘launch and sustain a large-scale robot campaign’. And he then added this ominous rider: some of the ‘missile planes’ were ‘capable of carrying an atomic bomb from one continent to another’ [ ‘United States ready for push-button warfare’; ‘Guided missiles in Korean War: Deadly new US technique’, Sydney Morning Herald, 19 September 1952].

Agency reports of his comments were played down in the United States, where they evidently incurred the wrath of his superiors. Rear Admiral John Sides described the use of the Hellcat drones as an ‘interim measure’ before the development of ‘more effective guided missiles’, conceding that ‘it wouldn’t take much imagination to realize that there are better ways of doing this job.’ But he would give no further details: the Navy was ‘investigating the use of classified information in news dispatches on the employment of pilotless bombers in Korea’, but refused to elaborate [‘Korea robot raids “interim measure”’, New York Times, 19 September 1952]. Instead, Sides switched the focus from the aircraft to American lives. The object of the experimental programme observed by the Popular Mechanics correspondent earlier in the year was ‘to obtain air kills by individuals operating from beyond the range of the enemy’s armament’, he emphasised, and in Korea ‘a controller sitting in relative safety’ outside the range of anti-aircraft defences ‘had been able to direct an effective drop on the enemy positions.’ The previous Times report had already underlined the significance: ‘The planes were sacrificed but, of course, not a man was lost.’

On 22 September NBC broadcast a short Department of Defense film describing what it called the dawn of ‘a new era in warfare’ in Korea but which made no mention of nuclear weapons. Instead the commentary emphasised that the pilot of the ‘robot bomber’ was ‘safely out of range’ and that these ‘guided missiles’ might ‘someday eliminate the human element’ altogether :

‘The carrier USS Boxer launches guided missiles for the first time in combat, bringing the push-button war of tomorrow into present day reality. Defense Department films show the first mission of the robot bombers, weapons that may someday eliminate the human element from air war.

The robot missile is catapulted aloft. It is a semi-obsolete Hell Cat, carrying a one-ton bomb load and a television camera instead of a pilot.

Already in the air is the mother plane, with an observer who flies the drone by remote control. Side by side, missile and mother plane head for the target. Then the pilot, safely out of range of interception and anti-aircraft fire, guides the robot directly into the target with unerring accuracy.’

And this was, of course, the larger and sharper point. The reason drones were originally used to fly through the atomic cloud (though they were later replaced by crewed missions); the reason the Air Force needed a remotely operated aircraft to drop the next generation of nuclear weapons; the reason the Navy wanted ‘offensive drones’ and ‘robot missiles’ to attack heavily defended targets was to save the lives of American crews. It is the same mission that continues today in the US prosecution of what are its avowedly asymmetric wars: to ‘project power without vulnerability’.