As Donald Trump‘s grotesque unfitness for office becomes ever clearer – though to most of us it was as plain as a pikestaff long before the election – a central vector of concern has been his proximity to the nuclear codes. For background, I recommend Adam Shatz‘s essay in the LRB, ‘The President and the Bomb‘:

What’s really terrifying about Trump’s control of the bomb is that it’s no aberration: in fact, it’s utterly normal. Democratic politicians – presidents, and would-be presidents – have spoken with no less gusto of their willingness to ‘keep all options on the table’. When Obama said that he wouldn’t consider using nuclear weapons against Pakistan at a presidential debate in 2008, Hillary Clinton scolded him: ‘I don’t believe any president should make blanket statements with regard to use or non-use.’ The right to annihilate one’s enemies (or frenemies, as in the case of Pakistan) is a right no American leader can afford to relinquish, for fear that he or she would be accused of being a pushover, an appeaser – a pussy. (A president can only grab a pussy: he can’t be one.) When Obama tried to discuss a no-first-use declaration, his cabinet quickly dissuaded him. Although he achieved the nuclear agreement with Iran, averting a potential war, and expressed symbolic atonement on his visit to Hiroshima, he also oversaw a programme of nuclear modernisation, with a commitment to a trillion dollars in extra spending over thirty years, increasing America’s ability to crush its opponents in a first strike. Trump has happily inherited that programme, without, of course, crediting his predecessor.

Against this wretched backdrop, it’s worth revisiting America’s history of nuclear narcissism.

I first discussed this in my presentation of ‘Little Boys and Blue Skies‘ at a wonderful symposium ‘Through Post-Atomic Eyes‘ [see here, here, here and here], and I’ve now revisited it for the long-form version (which you can at last find under the DOWNLOADS tab). Here is part of that new essay (‘Little Boys and Blue Skies: Drones through post-atomic eyes‘):

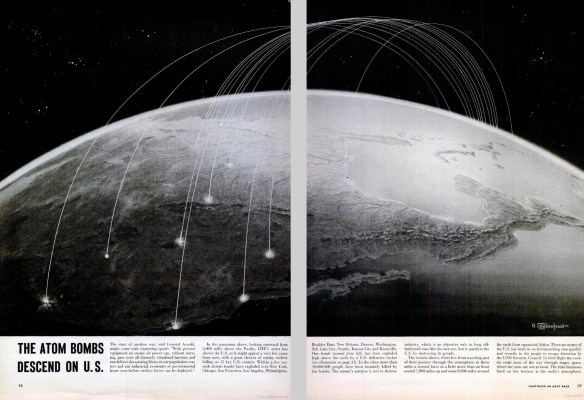

On 19 November 1945, barely 100 days after Hiroshima, Life published an illustrated essay entitled ‘The 36-Hour War’, which was informed by a report from General Henry ‘Hap’ Arnold as commander of the US Army Air Force to the Secretary of War. Although the opening paragraphs predicted that in the future ‘hostilities would begin with the explosion of atomic bombs on cities like London, Paris, Moscow or Washington’ – Arnold’s report had warned that ‘the danger zone of modern war is not restricted to battle lines’ and that ‘no one is immune from the ravages of war’ [1] – the global allusion of the text was dwarfed by Alexander Leydenfrost’s striking illustration of ‘a shower of white-hot rockets’ falling on Washington DC.

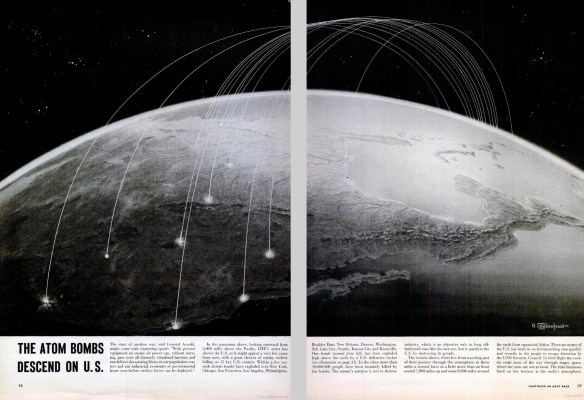

In case any reader should doubt the location of what the strapline called ‘the catastrophe of the next great conflict’, the next image sprawled across two pages and presented a vast panorama looking east across the United States from 3,000 miles above the Pacific: ‘Within a few seconds atomic bombs have exploded over New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Boulder Dam, New Orleans, Denver, Washington, Salt Lake City, Seattle, Kansas and Knoxville (sic)’ killing 10,000,000 people.

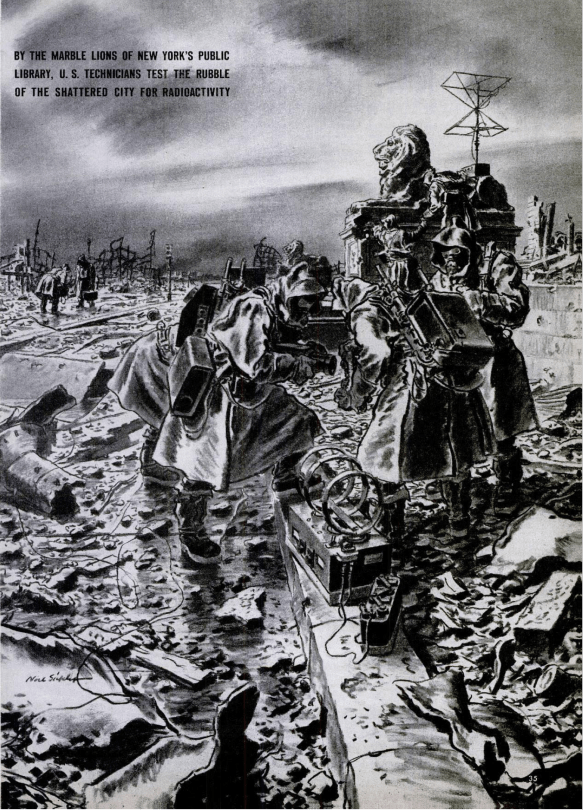

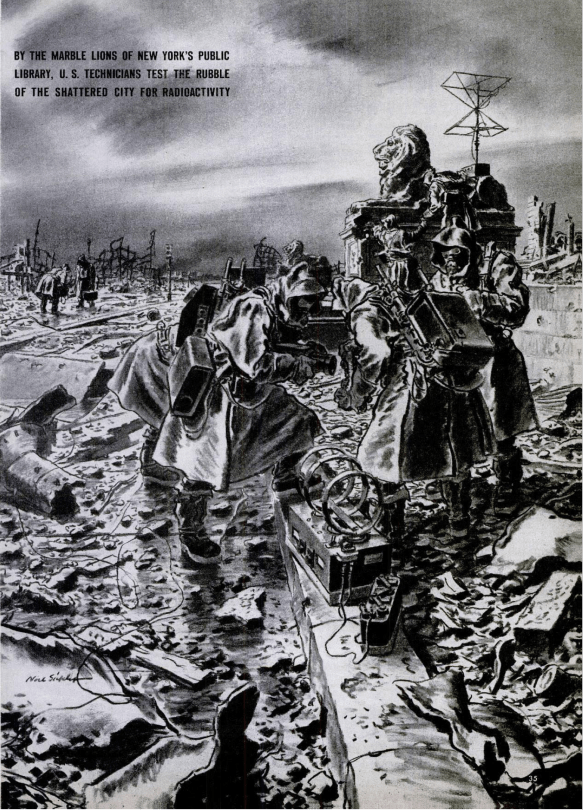

Arnold’s report had suggested that there were ‘insurmountable difficulties in an active defense against future atomic projectiles.’ Now Life warned that ‘low-flying robot planes’ were even more dangerous because they would be more difficult to detect by radar – and ‘radar would be no proof at all against time bombs of atomic explosive which enemy agents might assemble in the U.S’ – so that defence was more or less impossible. A counterattack could be launched (against an enemy who remained unidentified throughout the essay), but nuclear strikes would surely be followed by invasion. By then, the US would have suffered ‘terrifying damage’: ‘All cities of more than 50,000 have been levelled’ and New York’s Fifth Avenue reduced to a ‘lane through the debris.’

That final image was unique; it was the only one to envision a nuclear attack from the ground. Perhaps that was unsurprising; the power of the image – ‘the nuclear sublime’ – was one of the central objectives of the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. ‘The weapon’s devastating power had to be seen to be believed,’ Kyo Maclear observed, in Moscow as well as in Tokyo. And above all, literally so, it was designed to be seen from the air. During the seven years of the US occupation of Japan the effects on the people who lived and died in the irradiated rubble were subject to strict censorship. Still photographs could not be published – professionals and amateurs were ordered to burn their films and prints (fortunately some refused and hid them instead) – while Japanese media and even US military film crews had their documentary footage embargoed. In their place were endless images of the vast cloud towering into the sky. In fact Life had published a series of aerial views of the ‘obliteration’ of Hiroshima and the ‘disembowelling’ of Nagasaki just three months before its speculations on the 36-hour war. All those high-altitude views, and the maps that accompanied them, planed away the field of bodies: all that could be seen, deliberately so, were levelled spaces and superimposed concentric circles. In the studied absence of a visual record it was left to the imagination of writers to convey the effect of the bombs on human beings. And yet, as often as not, it was the bodies of Americans that filled the frame.

Philip Morrison’s remarkable essay for the Federation of American Scientists was at once the best informed and the most exemplary. Morrison was a former student of Oppenheimer who had worked with him on the Manhattan Project, and in July 1945 he was sent to the Mariana Islands as part of the team charged with assembling Little Boy. One month later he was on the ground in Hiroshima with the US Army mission to investigate the effects of the bomb. Their report was submitted in June 1946, but Morrison’s personal essay had appeared three months earlier and had already acknowledged the impossibility of conveying the enormity of the scene in dry and distanced scientific prose. It also proposed a solution.

‘Even from pictures of the damage realization is abstract and remote. A clearer and truer understanding can be gained from thinking of the bomb as falling on a city, among buildings and people, which Americans know well. The diversity of awful experience which I saw at Hiroshima … I shall project on to an American target.’

Warning that in any future war there would be twenty such targets – and not one bomb but ‘hundreds, even thousands’ – Morrison, as befitted someone who served with the US Army’s Manhattan Engineer District (the Manhattan Project), selected Manhattan.

‘The device detonated about half a mile in the air, just above the corner of Third Avenue and East 20th Street, near Grammercy Park. Evidently there had been no special target chosen, just Manhattan and its people. The flash startled every New Yorker out of doors from Coney Island to Van Cortland Park, and in the minute it took the sound to travel over the whole great city, millions understood dimly what had happened.’

After an endless chamber of horrors – bodies of old men ‘charred black on the side towards the bomb’, men with clothing in flames, women with ‘red and blackened burns’, and ‘dead children caught while hurrying home’; toppled brownstones, roads choked with rubble – he concluded that at least 300,000 people would have died: 200,000 ‘burned and cremated’ by volunteers, and the rest ‘still in the ruins, or burned to vapour and ash.

Hard on the heels of the Army in Hiroshima was the US Strategic Bombing Survey, whose findings were rendered in the same, impersonal voice that Morrison found wanting. But in the concluding section of its report, the authors confessed that investigators had been bothered by the same troubling question as Morrison: ‘What if the target for the bomb had been an American city?’ They provided rough and ready answers, which they accepted had ‘a different sort of validity’ from the measurable data used in the preceding sections, but they insisted that their speculative calculations were ‘not the least important part of this report’ and that they were offered ‘with no less conviction.’ Acknowledging substantial differences between Japanese and American cities, the report none the less concluded that most buildings in American cities would not withstand an atomic bomb bursting a mile or a mile and a half from them, and that the vertical densities of high-rise buildings would produce large numbers of dead, injured and desperately sick people: ‘The casualty rates at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, applied to the massed inhabitants of Manhattan, Brooklyn, and the Bronx, yield a grim conclusion.

The most vivid, visceral contrast to the dry recitations of the official reports appeared on 31 August 1946, when the New Yorker devoted an entire issue to John Hersey’s epic essay on Hiroshima. It was based on interviews he had conducted with more than 40 survivors over three weeks in April. Written when he returned to New York, beyond the scrutiny of military censors, Hersey focused on six people whose stories he told in spare, unadorned prose (he later said he chose to be ‘deliberately quiet’ so that ‘the horror could be presented as directly as possible’). The essay was cinematic in its execution, cutting from individual to individual across the shattered city, and excruciating in its painstaking detail. Their splintered accounts combined a methodical matter-of-factness – the numbing one-thing-after-another of their acts of survival – with the almost unspeakable horror of what lay beyond: ‘Under many houses, people screamed for help, but no one helped; in general, survivors that day assisted only their relatives or immediate neighbors, for they could not comprehend or tolerate a wider circle of misery.’ Two of Hersey’s respondents were doctors, which enabled him to pan out across that vast sea of casualties (‘Wounded people supported maimed people; disfigured families leaned together’) and then bring the focus back to individuals: ‘Tugged here and there in his stockinged feet, bewildered by the numbers, staggered by so much raw flesh, Dr. Sasaki lost all sense of profession and stopped working as a skillful surgeon and a sympathetic man; he became an automaton, mechanically wiping, daubing, winding, wiping, daubing, winding.’ Hersey’s narrative moved carefully through the weeks after the blast until the results of radiation sickness began to take their toll and even the signs of a precarious normality became sinister: ‘a blanket of fresh, vivid, lush, optimistic green’ as wild flowers bloomed ‘among the city’s bones.

Surely this awful litany would turn the American public’s post-atomic eyes to Japan? In fact the extraordinary success of Hersey’s essay – the print run of 300,000 sold out, ‘Hiroshima’ was reprinted in many newspapers, broadcast on the radio in nightly instalments, and when it appeared in book form it became an immediate bestseller – served not only to dispel the claims of those who had sought to minimise the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; it also redoubled the fears of an attack on the continental United States. In consequence, it was not only the New Yorker but also New York that dominated the American atomic imaginary in the late 1940s and 50s. Even the first mass-market edition of Hiroshima confirmed that the preoccupation with American lives had not sensibly diminished. Hersey later said he had wanted his readers ‘to identify with the characters in a direct way’ – ‘to become the characters enough to suffer some of the pain’ – but the artist responsible for the cover of the paperback, Geoffrey Biggs, took that literally. His image showed what he described as ‘two perfectly ordinary people’ in ‘a city like yours or mine’: who happened to be Americans in an American city:

The publication of ‘Hiroshima’ was preceded by the two tests at Bikini Atoll, and in 1947 the official report on Operation Crossroads illustrated the vastly more spectacular effects of the second (Baker) shot by superimposing its towering cloud over Manhattan:

Perhaps the most iconic series of images of a post-atomic New York was painted by Chesley Bonestell and Birney Lettick. They accompanied John Lear’s contribution to Collier’s in August 1950, whose title seemed to evoke Hersey’s essay only to transpose it: ‘Hiroshima USA’. A prefatory note from the editor William Davenport insisted that nothing in the report was fantasy. While ‘the opening account of an A-bombing of Manhattan may seem highly imaginative,’ he wrote, ‘little of it is invention.’

It was based on the two US military surveys of Hiroshima, interviews with officials at the Atomic Energy Commission and the Pentagon, and advice from physicists, engineers, doctors and other experts. The description that followed was apocalyptic:

‘Aerial reconnaissance was impractical immediately after the blast because of the cloud of black grime that masked the lower city. Even after that cleared, it was only possible for the police helicopter squad to get a numb impression of the devastation. Streets could not be seen plainly. Many were blotted out entirely. In an area roughly 15 blocks long and 20 blocks across – from Canal Street north to Tenth and from Avenue B to Sullivan Street – there was now an ugly brown-red scar. A monstrous scab defiling the earth…

‘Rising gradually outward from this utter ruin … was all that was left of Manhattan between Thirty-Eighth Street and Battery Park.’

As this passage implies, however, Lear’s vantage point was far from Hersey’s, who had described ‘four square miles of reddish-brown scar, where everything had been buffeted down and burned’ but who was clearly more invested in the suppurating wounds and scarred flesh of the survivors. Consistent with the official sources from which Lear drew, his emphasis was instead on the geometries of destruction: only here and there did the bodies of ‘the burned, the crushed and the broken’ flicker into view. Still, the sting was in the tail. ‘Fortunately for all of us,’ Lear concluded fifty pages after his editor’s admonitory note, ‘the report you have just read is fiction.’ But ‘if it ever does happen, the frightfulness will almost certainly be more apocalyptic than anything described in these pages.’

‘For this documentary account is a conservative application to Manhattan Island of the minimum known consequences of explosion of one of the 1945 model A-bombs. And the Russians, if they once decide to attack us, surely will drop two or three or four of the 1950 models, each of which would ruin almost twice the area here circumscribed… In fact, one of the primary assumptions of current military planning for defense of the United States is that an enemy’s first move will be to try to disable not only New York but the entire Atlantic seaboard…’

Similar scenarios were regularly offered for other cities, including Chicago in 1950, Washington in 1953, Houston in 1955 and Los Angeles in 1961, and all of them dramatized their accounts through photomontages, maps and artwork.

Significantly, the burden of these accounts was on the effects of blast, burn and destruction. Hersey’s descriptions of radiation sickness in Hiroshima were not mirrored in the United States, where the government consistently minimized its dangers. For the benefit of the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy in February 1953 the Atomic Energy Commission superimposed the blast radius from the first hydrogen bomb detonated in the Marshall Islands the previous November (‘Ivy Mike’) over a map of Washington DC, and the conceit provoked laugher from members of Congress because the ‘zero point’ was centred on the White House not the Capitol. The high-yield thermonuclear blast of Castle Bravo on 1 March 1954 was of a different order, and its fallout contaminated thousands of square miles. To illustrate its extent the AEC superimposed the plume over the eastern seaboard of the United States. Had this bomb been detonated over Washington, then Philadelphia, Baltimore and New York would have become uninhabitable.

President Eisenhower insisted on the map remaining classified, and when the New York Times splashed across its front page ‘The H-Bomb can wipe out any city’ its map was centred on New York and emphasised physical damage and destruction:

I rehearse all this because in her reflections on ‘the age of the world target’ Rey Chow writes of ‘the self-referential function of virtual worlding that was unleashed by the dropping of the atomic bombs, with the United States always occupying the position of the bomber, and other cultures always viewed as the … target fields.’ Yet, as I have shown, a common – perhaps even the most common – American response to Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the years immediately after the war was precisely the opposite. To be sure, the preoccupation with American cities as targets was spectacularly self-referential. Peter Galison was not sure whether ‘the bombsight eye had already begun to look back’ before Hiroshima, but he had no doubt that analysts working in the atomic rubble started ‘to see America through the bombardier’s eye.’ In a further twist to the examples I have cited, he shows how this scopic regime was refracted so that US defence planning in the 1950s included a national programme of ‘self-targeting’ in which cities were required to transform large-scale maps of their communities into target zones for nuclear bombs: what Galison called a ‘new, bizarre yet pervasive form of Lacanian mirroring.’

[1] Third Report of the Commanding General of the Army Air Force to the Secretary of War (12 November 1945), p. 59

[2] ‘The 36-Hour War: Arnold report hints at the catastrophe of the next great conflict’, Life, 19 November 1945, pp. 27-35; see also Alex Wellerstein, ‘The 36-Hour War’, Restricted Data, at http://blog.nuclearsecrecy.com/2013/04/05/the-36-hour-war-life-magazine-1945, 5 April 2013.

[3] Kyo Maclear, Beclouded visions: Hiroshima-Nagasaki and the art of witness (New York: SUNY Press, 1998); Barbara Marcon, ‘Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the eye of the camera’, Third Text 25 (6) (2011) 787-97.

[4] ‘War’s ending’, Life, 20 August 1945, pp. 25-31. In an accompanying editorial on ‘The Atomic Age’, the unease of the magazine about the effects of the twin bombings haunted its uncertain prose. ‘Every step in [the] bomber’s progress has been more cruel than the last,’ the editors wrote. ‘From the very concept of strategic bombing, all the developments – night, pattern, saturation, area, indiscriminate – have led straight to Hiroshima, and Hiroshima was and was intended to be almost pure Schrecklichkeit [terror].’ The use of the German was deliberate; noting that the Hague ‘rules of war’ had been persistently violated during the war by both sides, the editorial insisted that ‘Americans, no less than Germans, have emerged from the tunnel with radically different standards and practices of permissible behaviour toward others’ (p. 32).

[5] It was this artfully staged geometry of destruction that enabled some apologists to treat Hiroshima and Nagasaki as no different from other Japanese cities that had been subject to US firebombing, and to erase the suffering of the victims of both air campaigns from the field of view.

[6] Philip Morrison, ‘If the bomb gets out of hand’, in One world or none (Federation of American Scientists, 1946) pp. 1-15; cf. The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Manhattan Engineer District, US Army, 29 June 1946, at http://www.atomicarchive.com/Docs/MED/index.shtml.

[7] ‘That the Survey had seldom, if ever, felt compelled to ask such a question as it pored over the ruins of Germany spoke to the sheer psychic effect of the magnitude of the new weapon’: Tom Vanderbilt, Survival City: Adventures among the ruins of Atomic America (Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press, 2002) p. 74.

[8] The effects of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (US Strategic Bombing Survey, submitted 19 June 1946; published version 30 June 1946) pp. 39-41. The published version included a selection of photographs, virtually all of them aerial views, and the only photograph showing a victim was of a Japanese soldier with superficial burns: bodies were rendered as biomedical objects. Although most of the images obtained by the Survey remained classified, many of them are now available in David Monteyne, Adam Harrison Levy and John Dower (eds) Hiroshima Ground Zero 1945 (Göttingen: Steidl, 2011).

[9] John Hersey, ‘Hiroshima’, New Yorker, 31 August 1946. Hersey later explained that he wanted ‘to write about what happened not to buildings but to bodies’ and ‘cast about for a form to do that’; he found it on the marchlands between T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland and Thornton Wilder’s The Bridge of San Luis Rey (which he read onboard ship on his way to Japan). See John Hersey, ‘The Art of Fiction No 92’ (interview with Jonathan Dee), The Paris Review 100 (1986) 1-23. For commentaries, see Dan Gerstle, ‘John Hersey and Hiroshima’, Dissent 59 (2) (2012) 90-94; Patrick Sharp, ‘From Yellow Peril to Japanese wasteland’, Twentieth Century Literature 46 (2000) 434-52; Michael Yaavenditti, ‘John Hersey and the American conscience: the reception of “Hiroshima”’, Pacific Historical Review 43 (1974) 24-49.

[10] The Bantam edition appeared in 1948; Hersey, ‘Art of fiction’.

[11] Paula Rabinowitz, American Pulp: how paperbacks brought modernism to Main Street (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014) p. 211.

[12] John Lear, ‘Hiroshima USA’, Collier’s, 5 August 1950, pp. 11-15, 60-63: 15.

[13] Lear, ‘Hiroshima USA’, 62. One year later the magazine devoted an entire issue to ‘The war we do not want’ purporting to describe the defeat and occupation of the Soviet Union; the conflict was punctuated by air strikes on Chicago, Detroit, New York, Philadelphia and Washington and missiles launched from submarines against Boston, Los Angeles, Norfolk (Virginia), San Francisco, and Washington. There were also Soviet nuclear strikes on London and US saturation strikes on the Soviet Union: Collier’s, 27 August 1951.

[14] Richard Hewlett and Jack Holl, Atoms for Peace and War 1953-1961: Eisenhower and the Atomic Energy Commission (Berkeley CA: University of California Press, 1989) p. 181. The map followed a press conference held by Rear Admiral Lewis Strauss, chairman of the AEC, who explained that by ‘any city’ he meant ‘the heart of Manhattan’: William Laurence, ‘Vast power bared’, New York Times, 1 April 1954. Strauss also shared with the press part of the briefing he had given the President; his reported remarks minimised any dangers from radioactivity: ‘any radioactivity falling into the test area would become harmless within a few miles’: ‘Text of statement and comments by Strauss on hydrogen bomb tests in the Pacific’, New York Times, 1 April 1954.

[15] Rey Chow, in ‘The age of the world target: atomic bombs, alterity, area studies’, in her The age of the world target: self-referentiality in warm theory and comparative work (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006) pp. 25-43: 41.