On 18 March 1971 most readers of the Washington Post were taken aback by Jack Anderson‘s latest column:

On 18 March 1971 most readers of the Washington Post were taken aback by Jack Anderson‘s latest column:

‘Air Force rainmakers, operating secretly in the skies over the Ho Chi Minh Trail, have succeeded in turning the weather against the North Vietnamese. These strange weather warriors seed the clouds during the monsoons in an attempt to concentrate more rainfall on the trails and wash them out…

‘Their monthly reports, stamped “Top Secret (Specat)” (Special Category), have claimed success in creating man-made cloudbursts over the trail complex. These assertedly have caused flooding conditions along the trails, making them impassable…

‘The same cloudbursts that have flooded the Ho Chi Minh Trail reportedly also have washed out some Laotian villages. This is the reason, presumably, that the air force has kept its weather-making triumphs in Indochina so secret.’

Among the Post‘s astonished readers was Dennis Doolin, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for East Asia and Pacific Affairs. Three years later he testified before a subcommittte of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations that this was the first he had heard of the operation. When he asked about it he had been assured that it had not affected agriculture in ‘friendly countries’ in the region, and told not to pursue the matter: information ‘was held in a special channel and access was very, very limited’ as a result of the ‘sensitivity of the operation.’

In fact Secretary for Defense Melvin Laird had categorically denied Anderson’s ‘wild tales’, but rumours continued to circulate and on 3 July 1972 the New York Times splashed Seymour Hersh‘s detailed report over its first two pages: ‘Rainmaking is used as Weapon by U.S.’ Based on ‘an extensive series of interviews’ with officials who declined to be named – sounds familiar, no? – Hersh claimed that the experiments had been initiated by the CIA in 1963 and that by 1967 the Air Force had been drawn in (though ‘the agency was calling all the shots’). And if that sounds familiar too, then so will the cautious, even critical response of the State Department: its officials protested that the program would be illegal if it caused ‘unusual suffering or disproportionate damage’, and that its wider political and ecological consequences had been left unexamined. Undeterred, advocates demanded: ‘What’s worse – dropping bombs or rain?’

Although Hersh claimed that the program – which he identified as Operation Popeye – was ‘the first confirmed use of meteorological warfare’ there was a back-story and a history. In 1872 the US Congress authorised the Secretaries of War and the Navy to test the relationship between artillery fire and rain propagation proposed by Edward Powers in his War and the weather (1871). Experiments in rainmaking continued into the twentieth century, but the military interest in weather and war was primarily concerned with the adverse effects of the one on the other: most famously in planning the D-Day invasion of Normandy (see here and here, and Giles Foden‘s novel, Turbulence).

But after the Second World War the prospect of ‘weaponising the weather’ re-enchanted the US military. James Rodger Fleming (‘The pathological history of weather and climate modification’, Historical studies in the physical and biological sciences 37 (1) (2006) 3-25; see also here, and his Fixing the sky: the checkered history of weather and climate control (Columbia University Press, 2010)) describes how research on cloud seeding at the General Electric Research Laboratory in Schenectady, New York had been transferred to the US military in 1946:

‘Planners generated scenarios that included hindering the enemyʼs military campaigns by causing heavy rains or snows to fall along lines of troop movement and on vital airfields, taming the winds in the service of an all-weather air force, or, on a larger scale, perhaps disrupting (or improving) the agricultural economy of nations and altering the global climate for strategic purposes. Other possibilities included dissipating cloud decks to enable visual bombing attacks on targets, opening airfields closed by low clouds or fog, relieving aircraft icing conditions, or using controlled precipitation as a delivery system for chemical, biological, or radiological agents. The military regarded cloud seeding as the trigger that could release the violence of the atmosphere against an enemy or tame the winds in the service of an all-weather air force.’

In May 1954 Howard Orville, who had been the US Navy’s chief weather officer during the Second World War and was now chairman of President Eisenhower’s newly formed Advisory Committee on Weather Control, went public with the implications of the research in an article in Collier’s:

In May 1954 Howard Orville, who had been the US Navy’s chief weather officer during the Second World War and was now chairman of President Eisenhower’s newly formed Advisory Committee on Weather Control, went public with the implications of the research in an article in Collier’s:

‘It is even conceivable that we could use weather as a weapon of war, creating storms or dissipating them as the tactical situation demands. We might deluge an enemy with rain tp hamper a military movement or strike at his food supplies by withholding needed rain from his crops.’

Not surprisingly, results were at best equivocal, but Fleming argues that ‘weather modification took a macro-pathological turn between 1967 and 1972 in the jungles over North and South Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia’.

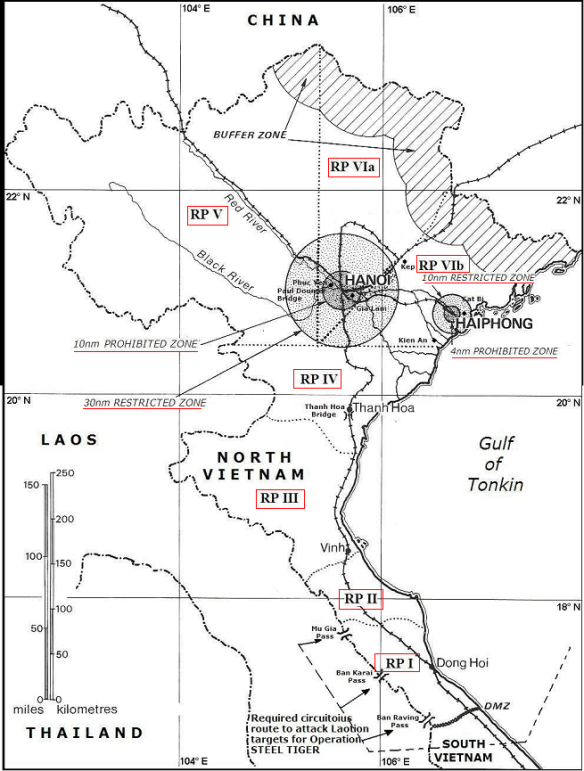

It was part of what John Prados (The bloody road: the Ho Chi Minh Trail and the Vietnam War, Wiley, 1998) calls the ‘wizard war’ waged by the United States to disrupt the main supply lines running from North Vietnam along the Ho Chi Minh Trail (or Duong Truong Road) through Laos and Cambodia to South Vietnam; other projects included the ‘electronic battlefield’ whose acoustic and seismic sensors detected movement along the trail network and triggered air strikes on target boxes (see ‘Lines of descent’, DOWNLOADS tab).

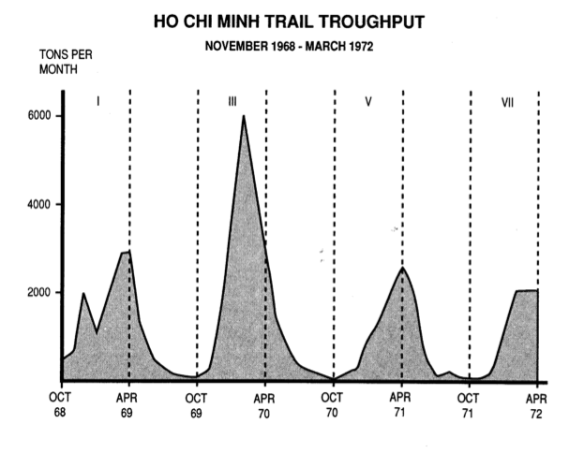

The Trail was in reality a complex, braiding network of roads and tracks, paths and trails, of which perhaps 3,500 kilometres was ‘motorable’. Although the system was maintained by 40-50,000 engineers, drivers and labourers, who used heavy equipment and gravel and corduroy surfaces to smooth the passage for trucks, most of the roads were dirt and virtually impassable during the south-west monsoon (May-September), so that the supply chain was highly seasonal:

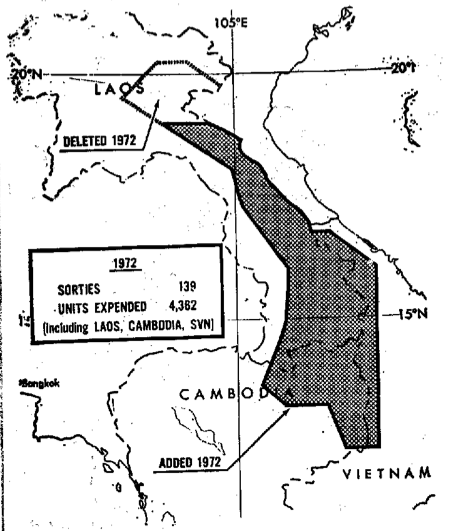

(Image from Herman Gilster, The air war in southeast Asia, Air University Press, 1993)

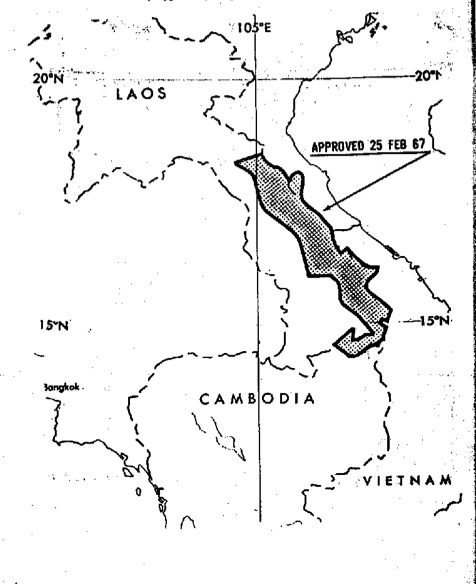

By 1966 it was becoming clear that efforts to interdict movement along the trail through conventional bombing had been unsuccessful (though this did little to halt the bombing). Pentagon scientists realised that if they could increase rainfall in selected areas this would not only soften roads, trigger landslides and wash out river crossings but also – the object of the exercise – continue these effects over an extended saturation period. From transcripts of a classified hearing by a subcommittee of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations in March 1974 we know that the US Office of Defense Research and Engineering initiated an experimental cloud-seeding program over the Laos panhandle in October 1966. Intelligence briefings blithely insisted that this would impose little or no additional hardship on the civilian population:

‘The sparsely populated areas over which seeding was to occur had a population very experienced in coping with the seasonal heavy rainfall conditions. Houses in the area are built on stilts, and about everyone owns a small boat. The desired effects of rainfall on lines of communication are naturally produced during the height of the monsoon season just by natural rainfall. The objective was to extend these effects over a longer period.’

56 pilot ‘seedings’ were carried out as Operation Popeye, and the military concluded that this was such a ‘valuable tactical weapon’ that the program should be continued over a wider area. According to Milton Leitenberg, in an unpublished study of Military R&D and Weapons Development prepared for Sweden’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in November President Johnson’s Scientific Advisory Committee came down against the military use of rainmaking techniques for both technical reasons (the results were inconclusive) and political ones (using meteorological techniques as weapons might jeopardise international scientific collaboration).

But in December the Joint Chiefs of Staff submitted three plans for future military operations in Indochina to the President, and all three involved extending Operation Popeye to ‘reduce trafficability along infiltration routes’.

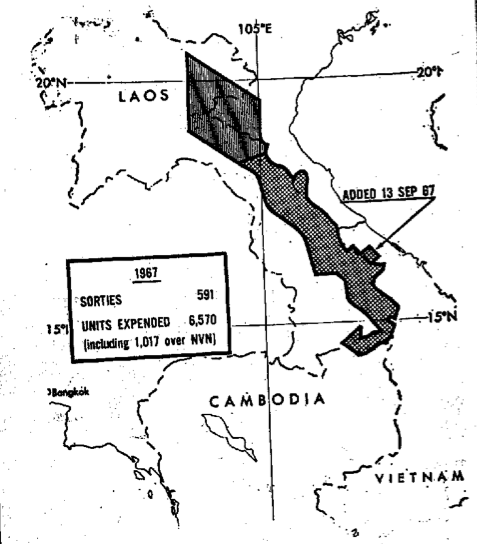

The operational phase (sometimes referred to as ‘Motorpool‘) began in March 1967, using three WC-130 aircraft – one of which is shown above, returning to Udorn Air Force Base in Thailand – and two RF-4C aircraft, all fitted with silver iodide ejectors. The aircraft displayed the standard Southeast Asia camouflage colours and markings but no unit identifiers, presumably because the operation was top secret. Although the missions were flown by the USAF’s Air Weather Service, and logged as standard ‘weather reconnaissance flights’, secret reports were forwarded to the Pentagon and the crews all had special clearance. Here is Howard Kidwell:

The operational phase (sometimes referred to as ‘Motorpool‘) began in March 1967, using three WC-130 aircraft – one of which is shown above, returning to Udorn Air Force Base in Thailand – and two RF-4C aircraft, all fitted with silver iodide ejectors. The aircraft displayed the standard Southeast Asia camouflage colours and markings but no unit identifiers, presumably because the operation was top secret. Although the missions were flown by the USAF’s Air Weather Service, and logged as standard ‘weather reconnaissance flights’, secret reports were forwarded to the Pentagon and the crews all had special clearance. Here is Howard Kidwell:

I kept hearing the call sign “Motorpool” used by two of crews in the 14th. When I inquired what they did, I got the usual reply that it was Top Secret and no one knew. I knew the crews and they wouldn’t say zip. This grows on a guy, and I had to find out what was going on. So, dummy me, I volunteered. Well, in a little while I was interviewed and told they would get a higher security clearance for me. In a few short weeks and I was told to come to Motorpool Ops for a briefing. (I found out later that friends and relatives in the states were contacted about me). The Lt Col in charge said the room had been swept for monitoring devices, etc., and I had one last chance to withdraw my volunteer statement. I had fleeting thoughts of flying over China, working for the CIA, you name it… but what the heck. I signed the statement and found out that I was going to make rain! Geez! I thought they were kidding!

Leitenberg claims that responsibility for the program was assigned to the office of the Special Assistant for Counterinsurgency and Special Activities, an agency with close operating links to the CIA (in fact U Dorn was also the operating base for the CIA’s Air America that supported covert operations in Indochina). Consistent with this security classification, the governments of Thailand and Laos were not informed about the operations: Doolin testified that the Lao government ‘had given approval for interdiction efforts against the trail system and we considered this to be part of the interdiction effort.’

By June the US Ambassador to Laos was enthusiastically reporting that:

‘Vehicle traffic has ground virtually to a halt… Our road-watch teams report that in many stretches … ground water has already reached saturation point and standing water has covered roads.’

By then, Motorpool had been joined by another covert operation, Commando Lava, described as an ‘experiment in soil destabilisation’. C-130 aircraft dropped pallet-loads of chelating compounds (’emulsifiers’) at choke points along the Trail in Laos to magnify the effect of the rains and, again, to extend the saturation period. The Ambassador was thrilled. Convinced that this ‘could prove a far more effective road interdictive device (at least in rainy season) than iron bombs and infinitely less costly’, he cabled Washington:

‘If we could combine these techniques with techniques of Operation Popeye, we might be able to make enemy movement among the cordillera of the Annamite chain almost prohibitive. In short, chelation may prove better than escalation. Make mud, not war!’

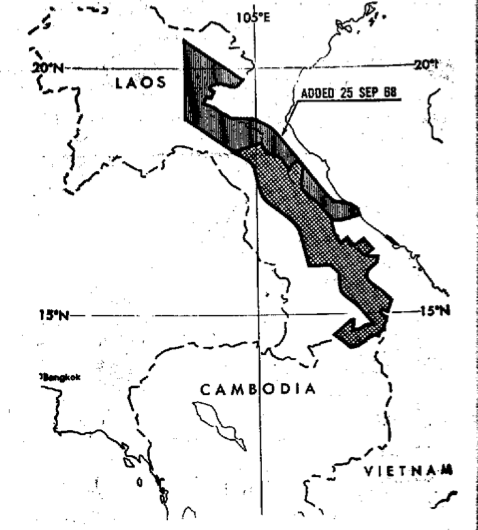

But Commando Lava was a failure, and Westmoreland cancelled it in October. The results for Popeye/Motorpool were far from conclusive either – the Defense Intelligence Agency later estimated that rainfall may have been increased by up to 30 per cent in limited areas – but the mission was regularly extended. Its coverage was constantly adjusted, and all seeding above North Vietnam was ended on 1 November 1968 when Johnson called a halt to the Rolling Thunder bombing campaign:

By the time the operation was ended 2,602 individual sorties had been flown. Prompted in part by a Senate resolution in 1973 that urged the US government to secure an international agreement outlawing ‘any use of an environmental or geophysical modification activity as a weapon of war’, and by the public release of the transcript of the secret Congressional hearings in 1974, the UN General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Prohibition of Military or Any Other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification Techniques (or ENMOD) in 1976. It came into force in October 1978: more here and here.

There were, of course, other, better known and hideously more effective versions of ecological warfare in Indochina: defoliating huge swathes of mangrove and rainforest with Agent Orange and other chemical sprays, and bombing the dikes in North Vietnam. But these weather operations, which combined minimum success with scandalous recklessness, now have a renewed significance. As late as 1996 the US Air Force was still describing weather as a ‘force multiplier’ and, by 2025, planning to deploy UAVs for ‘weather modification operations’ at the micro- and meso-scale so that the United States could ‘own’ the weather (strikingly, there is no discussion of any legal restrictions).

But today the equation has been reversed, and the US military has to contend not only with its projected capacity to change the weather but also – as I’ll discuss in a later post – with the effects of global climate change on its operations.