This is the seventh in a series of posts on Grégoire Chamayou‘s Théorie du drone; this one covers the second chapter of Part II, Ethos and psyche.

2. ‘That others may die’

Chamayou opens with a quotation from a French naval officer, Raoul Castex, on early submarine warfare. Castex was a naval strategist of the first water (he rose to the rank of Admiral, though he was a captain when he wrote the essay Chamayou cites). His views were canvassed as widely as those of Alfred Thayer Mahan, and they were set out in detail in his five-volume Théories strategiques published by the Société d’Editions Géographiques, Maritimes et Coloniales between 1929 and 1935. This was hailed as recently as 1995 in a report prepared for US Navy Doctrine Command by James Tritten as ‘perhaps the most complete theoretical survey of maritime strategy to ever appear.’

Chamayou opens with a quotation from a French naval officer, Raoul Castex, on early submarine warfare. Castex was a naval strategist of the first water (he rose to the rank of Admiral, though he was a captain when he wrote the essay Chamayou cites). His views were canvassed as widely as those of Alfred Thayer Mahan, and they were set out in detail in his five-volume Théories strategiques published by the Société d’Editions Géographiques, Maritimes et Coloniales between 1929 and 1935. This was hailed as recently as 1995 in a report prepared for US Navy Doctrine Command by James Tritten as ‘perhaps the most complete theoretical survey of maritime strategy to ever appear.’

Castex was not fêted so enthusiastically in the 1920s, however, when his ‘synthesis on submarine warfare’ was seen as a defence of unrestricted German submarine attacks during the First World War. The first attacks had been against warships, but by early 1915 – and in large measure as a response to Britain’s naval blockade – the focus switched to merchant shipping. In the course of the war Britain lost over 12 million tons of merchant shipping to U-boats. In Castex’s view, the success of these attacks showed that the submarine was the instrument that would overturn Britain’s naval supremacy.

Britain bridled at the suggestion, and Castex’s supposedly exculpatory views were quoted in (mis)translation by Britain’s First Lord of the Admiralty at the Committee on Limitation of Armaments in Washington in December 1921; they were repudiated by the senior French naval delegate and provoked a fierce political and public controversy in Britain. The British delegation had gone to the Washington conference to demand the total abolition of submarine warfare: submarines were virtually impossible to detect, and there was little defence against them (depth charges became available in early 1916, but these had minimal effect). Before the War, Admiral Sir Arthur Wilson had denounced submarines as “unfair, underhand, and damned un-British”, and during the war there were repeated condemnations of the sinking of merchantmen (and arguments over their ‘noncombatant’ status). By 1921 the focus of debate had switched back to military targets, and the Admiralty was gravely concerned that the ‘battlefleets of the world” – crucially, of course, those of the Royal Navy – “would be at the mercy of flotillas of submarines of improved design.” Britain’s position was opposed by France, Italy and Japan, and the attempt at abolition failed. Chamayou doesn’t bother with any of this detail – it’s all back-story and you can find much more here – but its relevance for drone warfare and campaigns against it should be obvious.

In his synthesis Castex noted that the practitioners of submarine warfare believed that it had finally realised the dream of risk-less warfare. Here is the passage that Chamayou cites (and its prefiguration of Chamayou’s hunting thematic could not be plainer):

‘They were invulnerable. War should be a game for them, a sport, a kind of hunting, where, having delivered and spread murder, all that would be left for them to do would be to revel in the sight of their victims’ agony. Meanwhile they would be safe from retaliation and, once back in port, they would busy themselves with stories of their hunting prowess.’

In Chamayou’s view, drones have reincarnated this myth – and these sentiments – in even stronger terms. They have transformed the meaning of ‘going to war’; the traditional model of combat is now being displaced by an altogether different ‘state of violence’ that degenerates into slaughter or hunting. One no longer fights the enemy, Chamayou contends, the enemy is simply eliminated as though one were shooting rabbits.

In the sixteenth century Chamayou says that the iconography of Death often portrayed a soldier fighting a skeleton – most famously in Holbein’s Dance of Death – in a struggle that was always pointless because Death mocked his adversary and always triumphed in the end. The imagery has now been appropriated in this unofficial patch produced for Reaper crews, where the soldier now assumes the position of Death itself (and becomes synonymous with the MQ-9 Reaper); the slogan – which is in fact a parody of “That others may live”, used as a patch by the USAF’s Pararescue teams – gives Chamayou the title for his chapter.

In a sense, then, both the submarine and the drone trumpet asymmetry as virtue. And as that parallel implies, the pursuit of asymmetry is by no means novel. Here is Sebastian Junger:

A man with a machine gun can conceivably hold off a whole battalion, at least for a while, which changes the whole equation of what it means to be brave in battle…. Machine guns forced infantry to disperse, to camouflage themselves, and to fight in small and independent units. All that promoted stealth over honor and squad loyalty over blind obedience….

A man with a machine gun can conceivably hold off a whole battalion, at least for a while, which changes the whole equation of what it means to be brave in battle…. Machine guns forced infantry to disperse, to camouflage themselves, and to fight in small and independent units. All that promoted stealth over honor and squad loyalty over blind obedience….

As a result much of modern military tactics is geared toward maneuvering the enemy into a position where they can essentially be massacred from safety. It sounds dishonorable only if you imagine that modern war is about honor: it’s not. It’s about winning, which means killing the enemy on the most unequal terms possible. Anything less simply results in the loss of more of your own men.

Historical precedent cannot issue an ethical warrant, however, and Junger admits as much. Yet Chamayou notes that this is exactly the strategy used time and time again to justify drone warfare and to silence its critics. His example is an essay by David Bell directed at what he called ‘the increasingly vocal critics who doubt the morality, effectiveness, and political implications of “remote control warfare.”‘

‘[C]ritics tend to present this new frontier of warfare as something largely novel — a sinister science fiction fantasy come to life, and one that has the power to radically change the political dynamics of warfare. But if our current technology is new, the desire to take out one’s enemies from a safe distance is anything but. There is nothing new about military leaders exploiting technology for this purpose. And, for that matter, there is nothing new about criticizing such technology as potentially immoral or dishonorable. In fact, both remote control warfare, and the queasy feelings it arouses in many observers, are best seen as parts of a classic, and very old history.’

This is perfectly true, as far as it goes, and in my own work I have traced the historical curve of ‘killing at a distance’. I accept, too, that it is reasonable to ask those who object to killing from (say) 7,500 miles away to stipulate the distance from which they do consider it acceptable to kill (though I’m not sure how Chamayou would respond to such a question). As Bell wryly remarks, ‘None of today’s critics, as far as I know, have expressed any nostalgia for the pike, or other hand-to-hand weapons.’

Bell is a professor of history at Princeton, and I greatly admire his revisionist account of The first total war which troubles the usual identification of ‘total war’ with the bloody twentieth century and insists, instead, on Napoleon as the midwife of ‘warfare as we know it’. In fact, I’ve drawn on Bell’s work for my exploration of the French occupation of Egypt at the end of the eighteenth century.

Bell is a professor of history at Princeton, and I greatly admire his revisionist account of The first total war which troubles the usual identification of ‘total war’ with the bloody twentieth century and insists, instead, on Napoleon as the midwife of ‘warfare as we know it’. In fact, I’ve drawn on Bell’s work for my exploration of the French occupation of Egypt at the end of the eighteenth century.

But that’s the irony: Chamayou argues that it was precisely Europe’s colonial wars that epitomised the desire to kill others from a safe distance, whereas these are conspicuously absent from Bell’s defence of drone warfare. They don’t loom large in The first total war either, where Bell anticipates Chamayou’s challenge. He accepts that The first total war deals ‘only rarely with the world beyond Europe’ – the principal exception is indeed Egypt – and he acknowledges that ‘colleagues often suggested to me that the origins of modern total war are surely to be found on the early modern impperial frontier’:

‘Surely it was here, long before the French Revolution, that Europeans first dispensed with notions of chivalric restraint and waged brutal wars of extermination against supposed “savages”. Did not Europeans learn their worst behavior from imperial encounters in Asia, Africa, and the Americas?’

His answer, in fact, is no:

‘The horrendous slaughters of the Reformation-era wars of religion began well before most European empires had developed much beyond trading posts, and the worst examples occurred in the German states, which had no colonies. The development of the French and British overseas empires coincided with the introduction of relative moderation and restraint into European warfare, not with their disappearance.’

Bell attributes this state of affairs to the ‘dependence’ of Europeans on indigenous populations. When later imperial armies embarked on Kipling’s ‘savage wars of peace’ in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, he argues, ‘the colonial setting mostly offered Europeans a laboratory for testing their own preexisting ideas about war’: ideas that had been honed, so he insists, by the Napoleonic wars that are the focus of his book.

These are convenient and far from uncontroversial claims, but three riders are necessary that, taken together, reinstate the importance of colonial and imperial modalities of power.

First, Bell’s book glosses over the extraordinary violence of the French occupation of Egypt between 1798 and 1801, including the terrible victory at the Battle of the Pyramids and the French army’s savage and exemplary response to two insurrections in Cairo (he’s not alone: remarkably, Edward Said does much the same in Orientalism). The violence included close-quarter butchery but also stand-off artillery bombardments that rained shells down onto the city from the Citadel above. Here is an eye-witness account of the first insurrection:

‘The situation worsened by the time of the afternoon prayer. Violence and the atmosphere of siege increased. At that point (the French) fired their guns and bombarded the houses and the quarters, aiming especially at al-Azhar. They trained cannons and mortars on it, as well as on the positions of the fighters close to it, such as Ghawriya Market and al-Fahhamin. When this bombardment fell on the people, it was something which they had never witnessed in their whole life… ’

Second, whatever the origins of those ‘ideas about war’ – and they were, I think, clearly multiple – they were put into often spectacular effect during the colonial wars of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. And it is those wars that show the most direct continuity with the places and the peoples who are now condemned to live and die under the shadow of the drone.

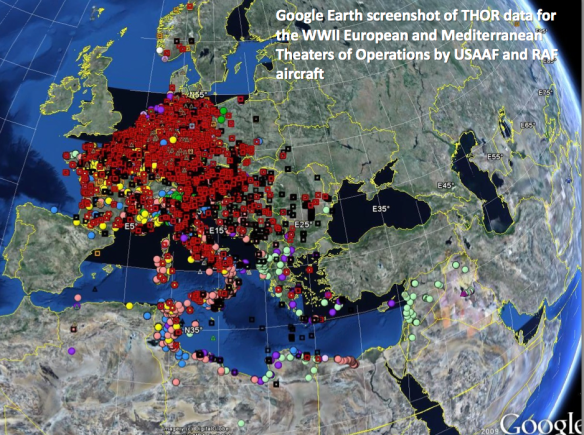

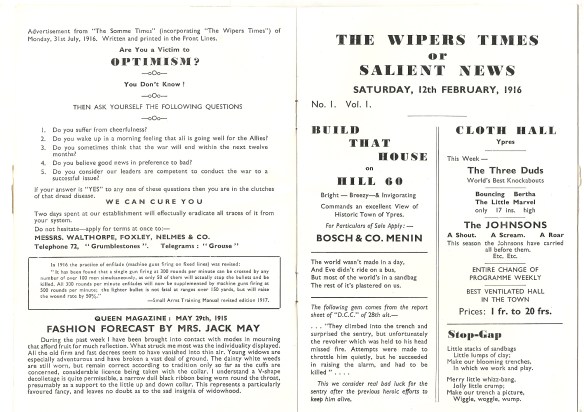

Third, as Chamayou shows in his discussion of ‘Counterinsurgency from the Air’, so-called ‘air control’ in the early twentieth century was an intrinsically colonial doctrine. The first experiments in bombing from aircraft took place over Libya before the First World War, and while bombing of civilian targets in Britain, France and Germany took place in the last years of the war, the use of airpower against peoples who had no capacity to strike back was a cornerstone of British policy in Iraq, Afghanistan and on the North-West Frontier of British India.

Chamayou argues that defenders of drone warfare who invoke the ‘nothing new under the sun’ argument do so in an attempt to relativise, even sedate contemporary violence. They invoke historical precedent – in effect: ‘This has happened time and time again before, so why all the fuss now?’ – but then fail to describe the bloody continuity that yokes past to present. Hence, as Chamayou concludes: ‘The drone is the weapon of an amnesiac post-colonial violence.’

My own inclination is to press this further. In The Colonial Present I suggested that what Chamayou describes here as a version of postcoloniality – I still think that term sadly premature – is haunted by Terry Eagleton‘s ‘terrible twins’: amnesia and nostalgia. Or, as Eagleton put it, ‘the inability to remember and the incapacity to do anything else.’ Drone strikes in Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia and elsewhere not only suppress the wretched consequences of previous ‘air control’ regimes but also yearn for the swagger and seemingly effortless domination that they imposed.

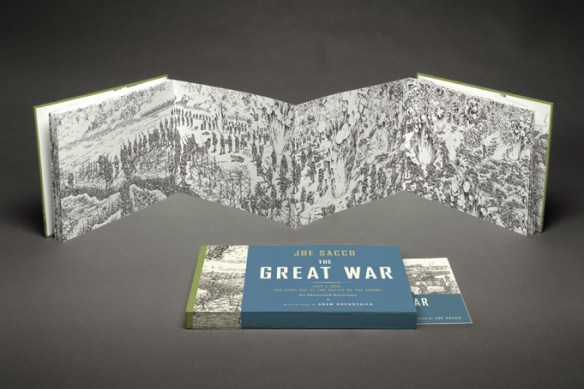

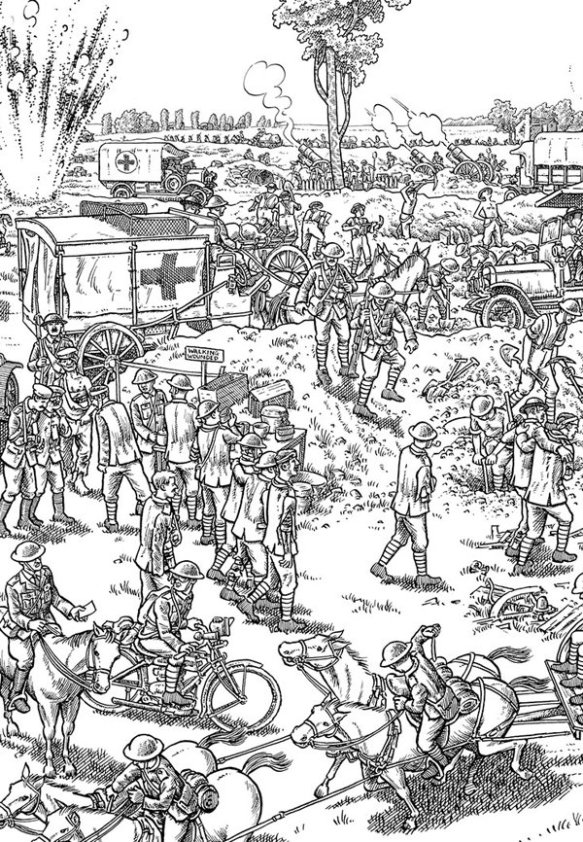

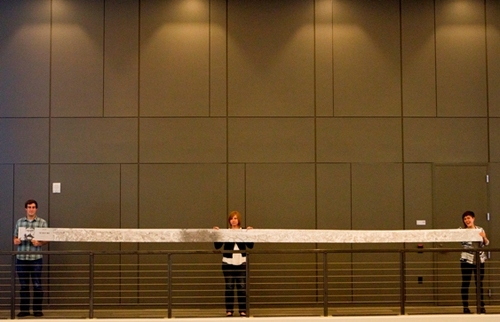

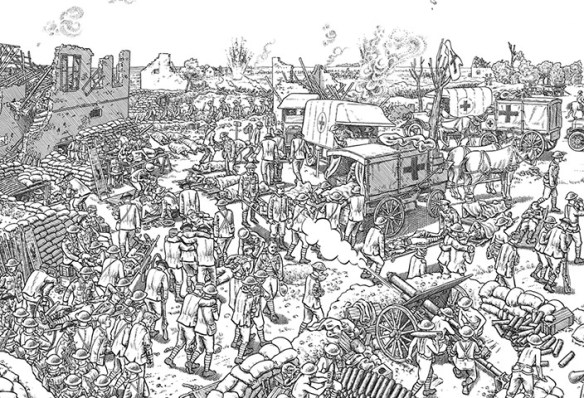

The first is Emily Mayhew‘s Wounded: from Battlefield to Blighty 1914-1918, which I noted in an earlier post; for editions outside the UK the subtitle becomes A new history of the Western Front. I’ve now read it, and admire its substance but also its style enormously. It’s based on painstaking research, literally so, and yet the main chapters read like a novel, and the analytical-bibliographic apparatus has been artfully moved to the Notes where it becomes a model of clear, concise and thought-provoking commentary rather than a cage that hobbles the narrative.

The first is Emily Mayhew‘s Wounded: from Battlefield to Blighty 1914-1918, which I noted in an earlier post; for editions outside the UK the subtitle becomes A new history of the Western Front. I’ve now read it, and admire its substance but also its style enormously. It’s based on painstaking research, literally so, and yet the main chapters read like a novel, and the analytical-bibliographic apparatus has been artfully moved to the Notes where it becomes a model of clear, concise and thought-provoking commentary rather than a cage that hobbles the narrative. The second is Ken MacLeish‘s Making war at Fort Hood: life and uncertainty in a military community. I met Ken at a workshop in Paris last year, and if you read anything better this year – in style and substance – than his Chapter 2 (‘Heat, weight, metal, gore, exposure’) I’ d like to know about it. The combination of ethnographic sensitivity, elegant prose, and a theoretical sensibility that Ken wears with confidence and displays with the lightest of touch is simply stunning.

The second is Ken MacLeish‘s Making war at Fort Hood: life and uncertainty in a military community. I met Ken at a workshop in Paris last year, and if you read anything better this year – in style and substance – than his Chapter 2 (‘Heat, weight, metal, gore, exposure’) I’ d like to know about it. The combination of ethnographic sensitivity, elegant prose, and a theoretical sensibility that Ken wears with confidence and displays with the lightest of touch is simply stunning.