Seeing like a military

I’ll be talking about ‘Seeing like a military‘ at the Association of American Geographers’ Annual Meeting in Tampa (home of Joint Special Operations Command!) 8-12 April 2014, and here’s the abstract:

Modern war has long placed a premium on visuality, but later modern war deploys new political technologies of vision and incorporates them into distinctive modes of the mediatization and juridification of military violence. This paper sketches those general contours and then examines two episodes in more detail. Both were carried out by the US military. The first is a combat helicopter attack on unarmed civilians in New Baghdad in July 2007, the subject of a military investigation, a Wikileaks release (‘Collateral Murder’), and two documentary films (‘Permission to Engage’ and ‘Incident in New Baghdad’). The second is another combat helicopter attack, but this time facilitated by the crew of a MQ-1 Predator, on three civilian vehicles in Uruzgan province, Afghanistan in February 2010, which was the subject of a military investigation that has been documented in detail. I use these incidents to extend the debate about militarized vision beyond dominant discussions of ‘seeing like a drone’, and to raise a series of questions about witnessing and military violence under the sign of later modern war.

Modern war has long placed a premium on visuality, but later modern war deploys new political technologies of vision and incorporates them into distinctive modes of the mediatization and juridification of military violence. This paper sketches those general contours and then examines two episodes in more detail. Both were carried out by the US military. The first is a combat helicopter attack on unarmed civilians in New Baghdad in July 2007, the subject of a military investigation, a Wikileaks release (‘Collateral Murder’), and two documentary films (‘Permission to Engage’ and ‘Incident in New Baghdad’). The second is another combat helicopter attack, but this time facilitated by the crew of a MQ-1 Predator, on three civilian vehicles in Uruzgan province, Afghanistan in February 2010, which was the subject of a military investigation that has been documented in detail. I use these incidents to extend the debate about militarized vision beyond dominant discussions of ‘seeing like a drone’, and to raise a series of questions about witnessing and military violence under the sign of later modern war.

The title is obviously a riff on James C. Scott‘s Seeing like a state – not least his opening claim that ‘certain forms of knowledge and control require a narrowing of vision’ – and the abstract is really just a summary of previous posts on Militarized Vision (see also ‘Unmanning’ here), but I’ll provide updates as the work progresses.

I’m deep into the detailed investigation of the Uruzgan incident. Previously I’d worked from a transcript of communications between the Predator crew, the ground forces commander and others – hence ‘From a view to a kill’ (DOWNLOADS tab) – but the detailed investigation files are eye-opening and are beginning to suggest a different narrative.

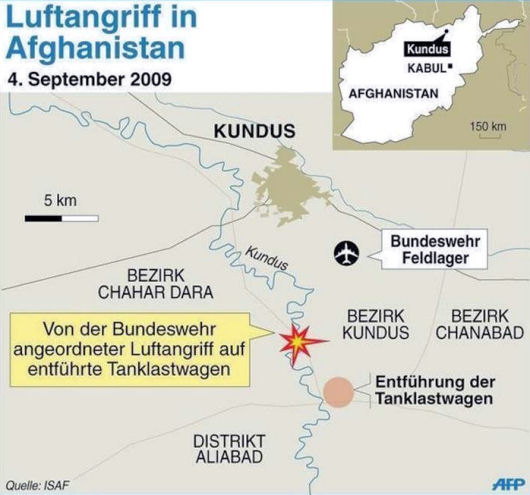

I’ve also widened the scope of the project (which, as the abstract suggests, was already about much more than the full motion video from Predators and Reapers). Although I won’t be talking about this in Tampa, I’m also examining another incident, an air strike on two tankers hijacked by the Taliban near Omar Kheil in Kunduz, Afghanistan in September 2009. The strike was carried out by USAF jets on the orders of the German Army (the Bundeswehr) from its Forward Operating Base at Camp Kunduz. It’s a complicated story that needs some background about (1) the Bundeswehr in Afghanistan and (2) air strikes and civilian casualties.

Bad Kunduz: the Bundeswehr and Afghanistan

After 9/11 and the US-led invasion of Afghanistan, Germany provided the third largest contingent of troops to NATO’s International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), but Bonn saw its primary role as stabilisation and reconstruction – in fact, the government refused to describe its military operations in Afghanistan as a war at all – and following this mandate Camp Kunduz [below] served as the base for a Provincial Reconstruction Team which was instructed to maintain a ‘light footprint’: so much so that troops jokingly referred to the base as ‘Bad Kunduz‘ (‘Spa Kunduz’) because it was so removed from the fighting.

But the security situation deteriorated, and Taliban attacks on German patrols and bases intensified. By 2007 the Bundeswehr had formed Task Force 47, made up of regular soldiers and elite troops from the Kommando Spezialkräfte or Special Forces, to adopt a more offensive posture and, in particular, to identify Taliban commanders who would be placed on ISAF’s Joint Prioritized Effects List (JPEL) for kill/capture missions. A detachment from Task Force 47 was also stationed at Camp Kunduz.

Still, in August 2009 Der Spiegel ran a story on ‘How the Taliban are taking control in Kunduz‘, and interviewed the base commander, Colonel Georg Klein, who described what the newspaper called the new ‘logic of the war’:

‘Kunduz has changed… I really don’t want to shoot at other people. They’re people too, after all. But if I don’t shoot, they’ll kill my soldiers.’

This ‘new logic’ would be demonstrated with hideous clarity a fortnight later. Yet – in principle, at least – it was constrained by a new Tactical Directive issued by General Stanley McChrystal in response to civilian casualties caused by coalition air strikes.

Air strikes and civilian casualties

Bombing had played a major role in the invasion of Afghanistan, and air strikes continued to be of decisive importance as the war with the Taliban continued (for more information, see here and here). They were also the main source of civilian casualties caused by coalition military operations; as the air war was stepped up and the body count soared so public hostility increased.

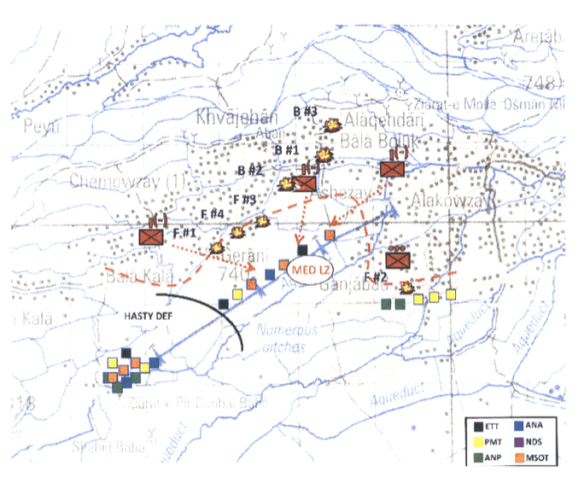

On 4 May 2009, just four months before the Kunduz air strike, there was yet another serious incident in which, according to a field investigation by the International Committee of the Red Cross, at least 89 civilians were killed in a series of air strikes near the village of Garani (sometimes spelled Gerani or even Granai) in the district of Bala Baluk in Farah province. Afghan forces had moved to engage the Taliban, supported by ISAF advisers, and as the fighting intensified they were reinforced by a detachment of US Marines. Close Air Support (CAS) was requested, and the first air strikes were carried out by F/A-18F jets (shown as #F1-4 in the graphic below). In the early evening their fuel reserves became too low to continue, and they were replaced by a B-1 bomber which made three further strikes (#B1-3). In the first strike, three 500 lb GPS-guided bombs were dropped; in the second, two 500 lb and two 2,000 lb bombs were dropped; and in the third a single 2,000 lb bomb was dropped. You can find images of the aftermath at Guy Smallman‘s gallery here.

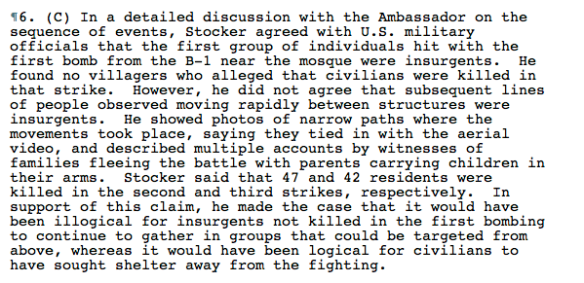

The ICRC report on the incident has never been published, in accordance with its usual practice, but Wikileaks released a cable from the US Ambassador in Kabul describing his meeting with the ICRC’s Head of Mission on 13 June to discuss the results. The ambassador praised the Head of Mission as ‘one of the most credible sources for unbiased and objective information in Afghanistan’ and accepted that the investigation was ‘certainly exhaustive’. But the casualty estimates were considerably higher than those made by ISAF’s own military investigation, from which I’ve taken the map above.

According to the Executive Summary prepared for US Central Command, ‘we will never be able to determine precisely how many civilian casualties resulted from this operation’. The military investigation concluded that 26 civilians had been killed but did ‘not discount the possibility’ that there were many more, and its authors also noted the ‘balanced, thorough investigation’ carried out by the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission that cited ‘as many as 86 civilian casualties’. Other reports claim as many as 147 civilians were killed.

The details of the military’s own investigation remain classified; General David Petraeus promised to show the strike video from the B-1 bomber in a press briefing (see also here), but it has never been released, though Wikileaks reportedly had an encrypted version in its possession (the issue formed part of the US government’s case against Bradley/Chelsea Manning). Although the CENTCOM report of 18 June ‘validated the lawful military nature of the strike’, it also expressed grave concern at ‘the inability to discern the presence of civilians and assess the potential collateral damage of those strikes’, and its recommendations included an immediate review of guidance ‘for employment of kinetic weapons, to include CAS, in situations involving the potential for civilian casualties.’

On 2 July McChrystal updated the existing Tactical Directive of October 2008 with a revised Tactical Directive – parts of it remained classified, but the ‘releasable’ version is here – which insisted that

‘We must avoid the trap of winning tactical victories – but suffering strategic defeats – by causing civilian casualties or excessive damage and thus alienating the people.’

Among other provisions, the directive specifically instructed commanders to ‘weigh the gain of using CAS against the cost of civilian casualties’. This is, of course, a requirement under international humanitarian law, but McChrystal went further and tightened the Rules of Engagement to such a degree that David Wood could write of the US Air Force ‘holding fire over Afghanistan’. Lessons from the incident were also incorporated into US Marine pre-deployment briefings (here; scroll down) and it was also used as the basis for a ‘tactical decision-making’ module in the US Army’s Afghanistan Civilian Casualty Prevention Handbook (June 2012) (pp. 58-67). But these lessons hadn’t been learned in time to prevent the tragedy that took place near Kunduz on the night of 3/4 September 2009.

The Kunduz air strike

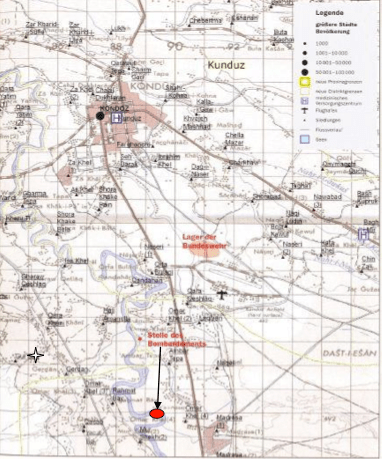

At 8 p.m. on 3 September Colonel Klein received a report that two tanker trucks had been hijacked by the Taliban as they drove south through Kunduz province (‘Entführung der Tanklastwagen’ on the map above). Thomas Ruttig provides an excellent overview of how what the Bundeswehr called ‘the Incident at Coordinate 42S VF 8934 5219’ unfolded here:

‘ The trucks were owned by an Afghan private company and contracted to deliver airplane fuel to ISAF forces. When the two hijacked lorries got stuck crossing a shallow riverbed at the border between Aliabad and Chahrdara districts, away from the main road, in the middle of a night in Ramadan, the Taliban mobilised the inhabitants of nearby villages more or less under their control to pump the fuel out and get the lorries going again. A large number took the offer up. Meanwhile, with the help of ISAF air reconnaissance, the immobilised trucks were located. This was done by a B-1 bomber which had cameras on board so strong they could even identify the weapons carried by the hijackers.’

The B-1 had to withdraw in the early hours of the morning because it was running low on fuel, and according to some reports the US Air Force was unwilling to provide replacement aircraft unless there were ‘Troops in Contact’ (TIC) with the Taliban. Klein decided to confirm a TIC – even though his troops were not at the scene – and two F-15E fighter jets flew right over his Forward Operating Base and then took up their station near the tankers at 0108. These aircraft (the two shown below were photographed over eastern Afghanistan) are operated by two crew members, a pilot and a weapons systems officer, and are equipped with Forward-Looking Infrared Sensors that, as Rutting notes, ‘portrayed people on the ground only as black spots.’ The two jets eventually carried out an airstrike at 0150.

What is particularly interesting about all this is that – in the wake of McChrystal’s revised Tactical Directive and tightened Rules of Engagement – the American pilots of the two F15-Es were markedly reluctant to strike. They were eventually persuaded to do so by Klein, yet he had no direct ‘eyes’ on the events as they unfolded. He was relying on a visual feed from the strike aircraft to a Remote Operated Video Enhanced Receiver [ROVER] terminal and on ground reporting from a single Afghan informant – classified as C-3, the lowest grade for ‘actionable intelligence’ – who was communicating by telephone with other ‘sub-contacts’ at the scene; there were apparently five intermediaries between the local source and Klein. At least one of them was a Special Forces intelligence officer from Task Force 47 who was with Klein in the Tactical Operations Center; some reports suggest that he believed that four Taliban leaders on the JPEL were at the scene.

The 15-page (redacted) cockpit transcript is here; all times shown there are Zulu (i.e. GMT), but here I revert to local time to reconstruct what happened. Klein is with his Forward Air Controller codenamed ‘Red Baron’ – what the USAF calls a Joint Terminal Attack Controller or JTAC, which is how he appears in the transcript – in the Tactical Operations Centre at Camp Kunduz (marked as Lager der Bundeswehr on the map above and referred to as PRT KDZ in the SIGACT report below).

The JTAC first asks the pilots to ‘stay as high as possible’ so that they can transmit a wide-shot video of the scene to his ROVER-3 screen – although this isn’t the latest model the JTAC wants ‘the best picture possible to give the commander [Klein] the possibility to make a decision’ – and they paint the target with infrared. They are confident this won’t alert the people on the ground: ‘We got no friendlies in the vicinity of the target and I don’t believe the insurgents got N[ight] V[ision] G[oggles] to see the IR.’

The picture is poor and so the pilots fly lower; they offer to provide ‘a show of force’, which is a standard tactic in Afghanistan accounting for 10 per cent of all Close Air Support sorties (though, as this map shows, it was less common in Kunduz compared to the south; I’ve borrowed the map from the remarkable work of Jason Lyall that I noted in a previous post on air strikes in Afghanistan).

The JTAC declines, saying ‘I want you to hide’, so that the people on the ground will have no warning of an impending attack, which leaves the pilots wondering ‘how we’d be able to drop anything on that as far as current ROE [Rules of Engagement] and stuff like that…’ They’re not sure that this meets the criteria for a TIC, which would allow them to engage, because they can’t see any German troops (‘friendlies’) on the ground: ‘We’ve got 50 to 100 people down there all claiming to be insurgents but I’m not seeing any imminent threat…’

One pilot accepts that the JTAC might have better information, but wants to ‘dig a little more’:

‘I’m really looking to find out status of the people inside [a nearby building 200 metres away] and then what’s inside the trucks. And then we can “show of force”, scatter the people, and then blow up the trucks.’

Again he offers to make a show of force but tells the JTAC they are ‘showing no CDE [collateral damage estimate] concerns within about 200 metres of that target.’ The pilots agree that Camp Kunduz is ‘pretty far away’ from the scene so that it is not visibly in imminent danger, and they wonder if ‘there is anyone else we can talk to’ before committing to a strike. They even contemplate contacting US Central Command’s Combined Air Operations Center in Qatar for clearance.

The pilots ask for confirmation that there would be ‘no civilians in the vicinity of the fragmentations’ from their two 500 lb GBU-38 bombs dropped on the tankers – ‘is that possible with no C[ollateral] D[amage] E[stimate]?’ the lead pilot queries – and again they ask the JTAC to confirm that everyone on the scene is ‘hostile’:

‘That’s affirmative. We got the intel information that everyone down there is hostile.’

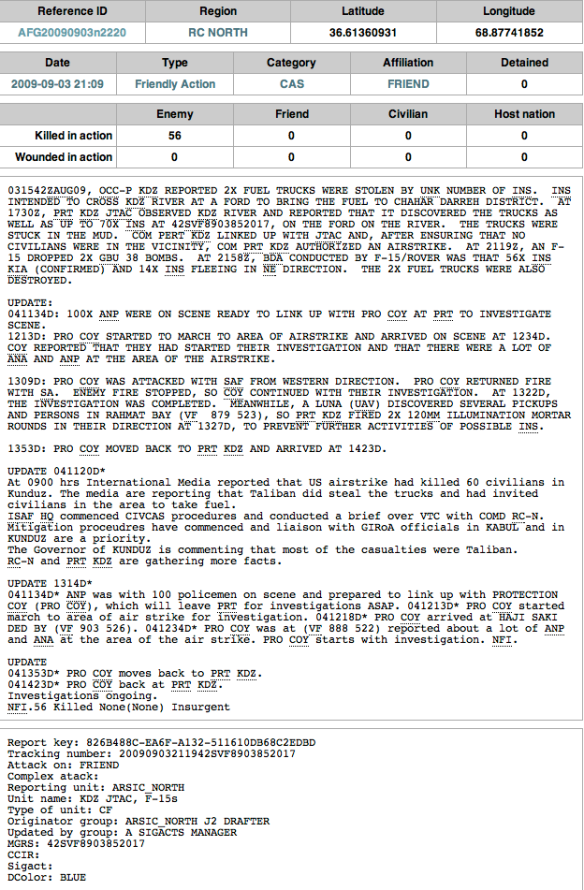

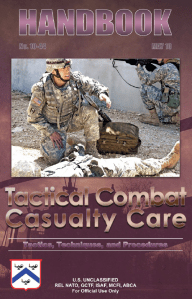

More vehicles are arriving on the scene and the JTAC insists that this is now a ‘time-sensitive target’. He then passes the pilots the standard 9-line briefing for a strike (see left). The first three lines are ‘not applicable’ because the aircraft are already on the scene, but the JTAC specifies the altitude, the target (‘insurgents on sandbank with 2 stolen trucks’), target location and mark, repeats ‘no friendly forces in area’, and asks them to remain on station for a Battle Damage Assessment.

More vehicles are arriving on the scene and the JTAC insists that this is now a ‘time-sensitive target’. He then passes the pilots the standard 9-line briefing for a strike (see left). The first three lines are ‘not applicable’ because the aircraft are already on the scene, but the JTAC specifies the altitude, the target (‘insurgents on sandbank with 2 stolen trucks’), target location and mark, repeats ‘no friendly forces in area’, and asks them to remain on station for a Battle Damage Assessment.

As the target is designated by the pilots, they ask the JTAC whether he is ‘trying to take out the vehicles or are you trying to take out the pax [people]?’

‘We’re trying to take out the pax.’

They again ask the JTAC to confirm that there are no friendlies in the vicinity, and he reports that they are all ‘safe’ at Camp Kunduz ‘roughly fifteen click to the east.’ (In fact, the base is about 8 km to the north east, but the tankers are facing in the opposite direction and Ruttig estimates it would have taken them an hour or so to reach the base on the rough, unpaved roads of the region).

The pilots still have misgivings: ‘something doesn’t feel right but I can’t put my thumb on it.’ They debate between themselves whether ‘in accordance with our ROE right now’ they should obtain higher-level clearance. If troops are not in imminent danger clearance is required from ISAF Headquarters in Kabul, and if there is a risk of civilian casualties clearance would need to be obtained from NATO’s Joint Force Command. Before they can reach a decision the JTAC jumps back in:

‘Clearance approved by commander he is right next to me.’

They’re not convinced. ‘The ground commander is clearing us hot but I don’t know if it meets the [hostile] intent or not.’

Still reluctant to strike – one pilot asks the other if ‘you’re saying it’s no imminent threat even though the JTAC said it was’ – the lead pilot tells the JTAC that they would prefer ‘to get down low, scatter the pax and blow up the vehicles’.

It then emerges that ‘ISR’ is en route, which presumably means a Predator with higher definition sensors, but before the remote platform can arrive the JTAC responds to the pilot’s repeated suggestion to scatter the people and then hit the trucks:

‘Negative, I want you to strike directly.’

Still no contact with the remote platform, and the lead pilot asks ‘one last [time]’ for confirmation that this is an imminent threat.

‘Yeah, those pax are an imminent threat, so those insurgents are trying to get all the gasoline off the tanks and after that they will regroup and we’ve got intel information about current ops so probably attacking Camp Kunduz.’

At 1.51 a.m. local time Klein gives the order: ‘Weapons release!’ The F-15Es are again ‘cleared hot’. Two 500lb GBU-38 bombs are released.

Here’s the strike video:

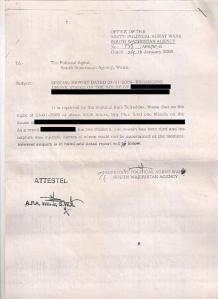

And here are the first military reports of the action (SIGACT or Significant Act) via Wikileaks:

From the ground

In contrast to these distanced observations, this is how the attack was described to Der Spiegel by one of the tanker drivers:

‘I can’t say how many airplanes there were or what type there were. But, starting at around 10 p.m., you could hear the sound of aircraft, though it was very faint. The plane must have been flying very high. But, yes, in Afghanistan, we recognize the sound of fighter jets. Some of the people around the trucks must have certainly heard the sound as well, but the majority of them were just jockeying to get fuel more quickly.

The armed men were getting nervous. They started making lots of phone calls again. I thought they were calling their leaders and asking for advice, asking what they were supposed to do now. At a certain point, some of them started shouting and waving their weapons around. They were screaming at the people to get away from the trucks because bombs were about to start falling. But no one wanted to miss an opportunity to get some free fuel. Then, some of the armed men even started running away…. I was sitting with some of the armed men along the river quite a way away from the trucks, maybe 50 meters (164 feet). The men were arguing over whether they should kill me right away or use me as a hostage to try to extort money from my company. I was very afraid — also of a possible bombardment….

At first, there was a loud droning, like what you hear when a generator short-circuits. Then there was a bright flash. I just let myself fall forward and went down underwater. Even from there, I could feel the shock wave. For a few seconds, it was as bright as day. Even the water was heating up. When I came out of the water, the whole area around the tanker trucks was on fire. It looked like the ground was spitting up fire, though it was just the fuel from the trucks. It was unbearably hot. There were bodies lying everywhere; they were completely carbonized.’

And this is how the scene was described to Amnesty International by another Afghan eyewitness:

“When we heard the planes flying everyone was scared and people began to flee the area at around 10.00 or 11.00 pm but then when people saw that the planes were only flying [and not bombarding] they returned to take the fuel. The number of the people were increasing every minute but after midnight the number started to decrease as many people obtained enough fuel and didn’t have enough containers to carry more fuel. It was around 1.00-1.30 am when the planes disappeared…

At about 1.45am we heard the planes return from our village. I tried to call my brother who was still at the scene. I knew that something was wrong if the planes returned but it seemed that the planes had blocked the telecommunication systems and we couldn’t get through to our relatives to call them to come back. Then I saw a big fire coming from plane and a big explosion with fire every where. I could see it from our village. Flames were very high and everyone rushed to the scene because most of the families had their children and family members out there.

As we arrived at the scene we could see nothing but flames and smoke. At that time it was almost around 3.00 [am] we saw the bodies burned and unidentifiable, others were badly injured and crying. The planes reappeared and then everyone fled in fear of being attacked and targeted. Some people got their family members’ bodies but not everyone. We couldn’t take the wounded people with us because the planes were still flying and we had to leave them there. As the planes disappeared, we went back and it was very early in the morning – everywhere were many bodies we couldn’t identify them at the time. Then every one carried the bodies to the villages and we had to bury some without knowing who they were. There were at least 20 children among the dead.”

Here is AFP video of the aftermath:

Ghaith Abdul-Ahad provide another extraordinary account in the Guardian:

What followed is one of the more macabre scenes of this or any war. The grief-stricken relatives began to argue and fight over the remains of the men and boys who a few hours earlier had greedily sought the tanker’s fuel. Poor people in one of the world’s poorest countries, they had been trying to hoard as much as they could for the coming winter.

“We didn’t recognise any of the dead when we arrived,” said Omar Khan, the turbaned village chief of Eissa Khail. “It was like a chemical bomb had gone off, everything was burned. The bodies were like this,” he brought his two hands together, his fingers curling like claws. “There were like burned tree logs, like charcoal.

“The villagers were fighting over the corpses. People were saying this is my brother, this is my cousin, and no one could identify anyone.”

So the elders stepped in. They collected all the bodies they could and asked the people to tell them how many relatives each family had lost.

A queue formed. One by one the bereaved gave the names of missing brothers, cousins, sons and nephews, and each in turn received their quota of corpses. It didn’t matter who was who, everyone was mangled beyond recognition anyway. All that mattered was that they had a body to bury and perform prayers upon.

If anybody still thinks that later modern war is somehow de-corporealized, they should read Abdul-Ahad’s full report. Ruttig takes up the story:

The number of people and specifically the number of civilians who were not ‘participating in hostilities’ killed in the strike is unclear to this day. It differs depending on the investigation report, some of which are published, while others remain classified. The still classified report by the then ISAF commander, General Stanley McChrystal – parts of which are cited in the report of the investigation committee of the German parliament, the Bundestag, that was published on 25 October 2011 – says “between 17 and 142 people” were killed. It does not seem to refer to killed civilians directly, but quotes local elders saying that possibly 30 to 40 civilians were killed. A report authored by a German military policeman who conducted an investigation at the location of the airstrike avoids stating whether there were what he called “non-involved civilians” among the dead …

The lawyers who brought the case before the Bonn court claim 137 people died, “undeniably many dozens of civilians”. An Afghan investigation commission, sent by President Hamed Karzai and led by police general Mirza Muhammad Yarmand, that was in the area between 4 and 10 September 2009, stated that 69 Taleban and 30 local residents – a term that leaves it open whether they were perceived as non-involved civilians or civilians that were supporting the Taleban in an operation – were killed.

An Afghan human rights group, Afghanistan Rights Monitor, which also conducted interviews with victims in the area, said on 7 September that 60 to 70 civilians were killed. Finally, UNAMA, as stated in its 2009 Protection of Civilians report (on p 18), after its own investigation, said that 74 civilians, including many children, had been killed. One of the problems, said UNAMA, was that the fireball produced by dropping munitions on the fuel tankers incinerated many of the bodies, making their identification impossible. However, according to probably the most extensive investigation, carried out by two Germans, Christoph Reuter, a journalist and occasional AAN author, and Marcel Mettelsiefen, a photographer, who repeatedly travelled to the region interviewing families and community members, ninety civilians “from children to old men” were killed. Reuter and Mettelsiefen published a moving book [Kunduz – above], naming the victims they had confirmed as having been killed and featuring photographs – ID documents, family photos and such – of each of the victims and their relatives. It was a powerful way to humanise the numbers of those killed and the scale of the loss to the community.

Military investigations and mediatizations

Immediately after the strike a senior ISAF officer made it clear that ‘The most important thing is for local official[s] to refute CIVCAS (civilian casualties).’ This is a leitmotif in ISAF’s response to incidents like this – CIVCAS reporting (or the lack of it) was a major preoccupation of the Uruzgan investigation – as the military battles to ‘control the narrative’ before the Taliban provide their own version of events. When McChrystal heard about the strike, however, he was reportedly furious:

He had just tightened up the rules for air strikes in the Afghanistan conflict. Bombs should only be dropped in the cases of acute danger to ISAF soldiers, in order to create the necessary trust in the foreign troops. The Kunduz air strike did not fit into this picture at all….

“Freely admit what we don’t know and say we are investigating,” he ordered the Germans. He assumed the first assessement that there had been no civilian victims had been incorrect. There was no way one could have made that determination from the air. The angered ISAF chief said he was “deeply disappointed.” The first statements from the Germans had been “foolishness.” He also said he had doubts that the rules of engagement had been followed and asked why soldiers were first sent to the scene three hours after the first accusations in the media of civilian casualties.

McChrystal was on the scene the next day – though Klein urged him not to go in case he was shot at – demanding to know why the Bundeswehr had waited so long to send a team to the strike site to conduct a ‘boots on ground’ Battle Damage Assessment and to provide a casualty report. On 9 September he announced the establishment of a Joint Investigation Board, which included a Canadian major-general (ISAF’s Air Component Element Director), officers from the USAF and the Bundeswehr, and military legal advisers (McChrystal’s detailed instructions to the Board are here).

Franz Josef Jung, Germany’s Minister of Defence, was soon on the offensive. He insisted that the Taliban’s seizure of the tankers ‘posed an acute threat to our soldiers’, that the strike was ‘absolutely necessary’ and that his officers had ‘very detailed information’ that the Taliban had planned to use the tankers to launch an attack. He was clearly displeased at McChrystal’s attitude (and determination), and five days after the strike had his Ministry set up a special task force (‘Group 85’) both to exploit an inside track to the investigation and to create a ‘positive image’ of the events. By then, an internal Bundeswehr inquiry had been completed. Its brief report described the incident as ‘Close Air Support’, determined that the Rules of Engagement for a ‘time-sensitive target’ had been followed and that Klein had the authority to order the strike, which was deemed ‘appropriate’, and declined to say whether ‘non-involved civilians’ had been killed alongside the Taliban.

But the subsequent, much more extensive report from ISAF’s Joint Investigation Board (75 pages plus 500 pages of attachments) flatly contradicted the German versions of what had taken place. According to Der Spiegel, which had seen the leaked report, the Board concluded that

‘Klein relied on only one person for “intelligence gathering,” which, even when combined with the aerial video images, was “inadequate to evaluate the various conditions and factors in such a difficult and complex target area.”

The report states it was not clear “what ROE (rule of engagement) was applied during the airstrike,” and that there was a “lack of understanding” by the German commander and his forward air controller (JTAC), “which resulted in actions and decisions inconsistent” with ISAF procedures and directives. Moreover, the report concludes, intelligence summaries and specific intelligence “provided by HUMINT (human intelligence) did not identify a specific threat” to the camp in Kunduz that night — the mandatory condition for an airstrike.’

In short, Klein knew that there were no ‘troops in contact’ but ‘believed that by declaring a “TIC” he would get the air support he wanted.’

Ironically, in 2008 Human Rights Watch had published a report showing that the likelihood of civilian casualties from air strikes in Afghanistan increased in TIC situations:

Ironically, in 2008 Human Rights Watch had published a report showing that the likelihood of civilian casualties from air strikes in Afghanistan increased in TIC situations:

‘…we found that civilian casualties rarely occur during planned airstrikes on suspected Taliban targets… High civilian loss of life during airstrikes has almost always occurred during the fluid, rapid-response strikes, often carried out in support of ground troops after they came under insurgent attack. Such unplanned strikes included situations where US special forces units — normally small numbers of lightly armed personnel — came under insurgent attack; in US/NATO attacks in pursuit of insurgent forces that had retreated to populated villages; and in air attacks where US “anticipatory self- defense” rules of engagement applied.’

In any event, Klein’s own account was markedly different. In a two-page report ‘for German eyes only’, der Spiegel revealed,

Klein portrays himself as the person who tried to rein in the American fighter jets. He wrote that he called for smaller bombs to be used “contrary to the recommendation of the B-1B and F-15E pilots.” The German colonel also says that he limited the use of force to the tanker trucks and people in the immediate vicinity and forbade strikes on people elsewhere on the river bank. He wrote that the bombs were dropped solely on the sandbank “in order to definitively exclude the possibility of collateral damage in the neighboring villages.”

In January 2010 a Bundestag committee started to investigate how such different versions emerged and to determine who was responsible for the strike. Its final report is here and supporting documents here. ISAF still refused to release its own report, even to the parliamentary investigation:

There are many other ways of ‘seeing’ what happened, of course, and the strike has been the subject of at least two films. The first, Raymond Ley’s Eine mörderische Entscheidung (2013), A fatal decision, is a docu-drama shot for German television. You can watch the trailer with English-language subtitles here. The full German-language film is available on YouTube here: it’s long, but if you start at 1:13:10 you’ll pick up the story as the informant is phoning in to the Forward Operating Base; the immediate prelude to the strike starts at 1:22:37. There’s an English-language discussion by Verena Nees here, which translates the title as A murderous decision but gives a good extended synopsis of the film. (The production company uses both English-language titles, but ‘fatal‘ is a better representation of the tenor of the film).

There are many other ways of ‘seeing’ what happened, of course, and the strike has been the subject of at least two films. The first, Raymond Ley’s Eine mörderische Entscheidung (2013), A fatal decision, is a docu-drama shot for German television. You can watch the trailer with English-language subtitles here. The full German-language film is available on YouTube here: it’s long, but if you start at 1:13:10 you’ll pick up the story as the informant is phoning in to the Forward Operating Base; the immediate prelude to the strike starts at 1:22:37. There’s an English-language discussion by Verena Nees here, which translates the title as A murderous decision but gives a good extended synopsis of the film. (The production company uses both English-language titles, but ‘fatal‘ is a better representation of the tenor of the film).

The second is Stefan and Simona Gieren‘s Kunduz (2012), a short film which builds on eyewitness reports to create a fictionalised German-Afghan photographer who witnessed the strike and tells his story to German doctors as he is is flown out from the area. You can see the trailer on vimeo here.

The second is Stefan and Simona Gieren‘s Kunduz (2012), a short film which builds on eyewitness reports to create a fictionalised German-Afghan photographer who witnessed the strike and tells his story to German doctors as he is is flown out from the area. You can see the trailer on vimeo here.

Preliminary observations

I still need to work my way through the Bundestag report in detail, but already several lines of inquiry are emerging that bear on my other case studies of ‘Militarized vision’.

(1) Militarized vision is not a constant. It’s an obvious point, but it can be sharpened because I don’t mean to confine this to the mundane (but still important) observation that political technologies of vision are constantly changing. So they are, but it’s clear that the ability of militaries to ‘see’ is differently and differentially distributed; there is a geography to militarized vision, and what Klein and his advisers saw on their screen was not what the F15E pilots saw – and that in turn was different to what the crew of the B-1 were able to see. This is about more than the resolution level of different imaging technologies, because:

(2) The politico-cultural construction of a wider ‘landscape of threat’ is crucial to the production and performance of a specific ‘space of the target’. In this case, the transition of the Bundeswehr‘s operational posture – the powerful sense of increasing and even impending Taliban attacks and the determination to take the offensive – clearly shaped the way in which Klein and those advising him (mis)read the developing situation. This in turn is shaped by developing legal geographies:

(3) The use of military force is clearly governed by international law which, as I’ve noted elsewhere, has an intimate relationship with technologies of vision. This extends beyond the requirements imposed by proportionality and distinction – including the US military’s ‘prosecution of the target’ and the ‘visual chain of custody’, though in this case it is notable that no military lawyers were involved in authorising the strike – because the legal armature that surrounds military violence is located at the intersection of international law, military law and domestic law. The relevance of McChrystal’s updated Tactical Directive and revised Rules of Engagement to the pilots’ field of vision is clear enough, but the refusal by Bonn to describe its military operations in Afghanistan as ‘war’ materially affected the way in which German law was brought to bear on Klein’s actions: his criminal prosecution was dropped soon after the government determined that the Kunduz affair was indeed a punctuation point – in fact an exclamation mark – in an armed conflict.

(4) And – to return to my first point from a different direction – what military investigations ‘see’ after an incident (and what they allow the public to see) is often radically different from what those caught up in the event-scene were able to see…

More to come.

Readings

There is a commentary on the strike by Constantin Schüßler and Yee-Kuang Heng,’The Bundeswehr and the Kunduz air strike 4 September 2009: Germany’s post-heroic moment?’, in European security 22 (30 (2013) 355-75. They explore not only the doctrine of force protection (in which risk is transferred to others in the field of view – see the still from Fatal Decision below – as I discussed in my commentary on what Grégoire Chamayou calls ‘necro-ethics’) but also the legal and media apparatus that enveloped the incident. For a more detailed treatment of the (il)legality of the strike, see Andreas Fischer-Lescano and Steffen Kommer, ‘Entschädigung für Kollateralschäden? Rechtsfragen anlässlich des Luftangriffs bei Kunduz im September 2009’, Archiv des Völkerrechts 50 (2) (2012) 156-990, which makes extensive use of the Bundestag investigation, and Lesley Wexler, ‘International Humanitarian Law transparency’, Illinois Public Law and Legal Theory Research Papers Series 14-11 (2013) available via ssrn here.

For a discussion of the political landscape within which the strike took place, see Timo Noetzel, ‘The German politics of war: Kunduz and the war in Afghanistan‘, International Affairs 87 (2) (2011) 397-417; Thomas Rid and Martin Zapfe, ‘Mission command without amission: German military adaptation in Afghanistan’, in Theo Farrell, Frans Osinga and James A. Russell (eds), Military adaptation in Afghanistan (2013) 192-218. For the ethical perspective, Anya Topolksi has an extremely interesting essay, ‘Relationality: an ethical response to the tensions of network enabled operations in the Kunduz airstrikes’ forthcoming in the Journal of military ethics. Finally, Christine G. van Burken has an essay on ‘The non-neutrality of technology‘ in Military Review XCIII (3) (2013) 39-47 that spirals around the Kunduz strike and some of the issues that are central to my own focus on the political technologies involved.