101 is the emergency number for Gaza and the rest of occupied Palestine. And perhaps I should begin with that sentence: I say ‘the rest of occupied Palestine’ because, despite Israel’s ‘disengagement’ from Gaza in 2005, Israel continues to exercise effective control over the territory which means that Gaza has continued to remain under occupation. It’s a contentious issue – like Israel’s duplicitous claim that the West Bank is not ‘occupied’ either (even by its illegal settlers) merely ‘disputed’ – and if you want the official Israeli argument you can find it in this short contribution by a former head of the IDF’s International Law Department here and here. The value of that essay – apart from illustrating exactly what is meant by chutzpah – is its crisp explanation of why the issue matters:

‘This does not necessarily mean that Israel has no legal obligations towards the population of the Gaza Strip, but that to the extent that there are any such legal obligations, they are limited in nature and do not include the duty to actively ensure normal life for the civilian population, as would be required by the law of belligerent occupation…’

Certainly, one of the objectives of Israel’s ‘disengagement’ was to produce what its political and military apparatus saw as ‘an optimal balance between maximum control over the territory and minimum responsibility for its non-Jewish population’. That concise formulation is Darryl Li‘s, which you can find in his excellent explication of Israel’s (de)construction of Gaza as a ‘laboratory’ for its brutal bio-political and necro-political experimentations [Journal of Palestine Studies 35 (2) (2006)]. (Another objective was to freeze the so-called ‘peace process’, as Mouin Rabbani explains in the latest London Review of Books here; his essay also provides an excellent background to the immediate precipitates of the present invasion). Still, none of this entitles Israel to evade the obligations of international law. Here it’s necessary to recall Daniel Reisner‘s proud claim that ‘If you do something for long enough, the world will accept it… International law progresses through violations’: Reisner also once served as head of the IDF’s International Law Department, and the mantra remains an article of faith that guides IDF operations. But as B’Tselem, the Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories, insisted in an important opinion published at the start of this year:

Even after the disengagement, Israel continues to bear legal responsibility for the consequences of its actions and omissions concerning residents of the Gaza Strip. This responsibility is unrelated to the question of whether Israel continues to be the occupier of the Gaza Strip.

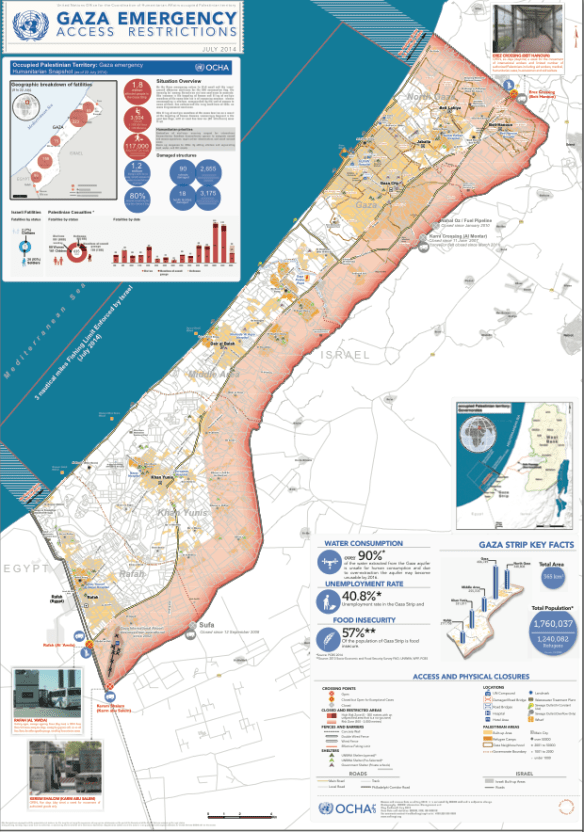

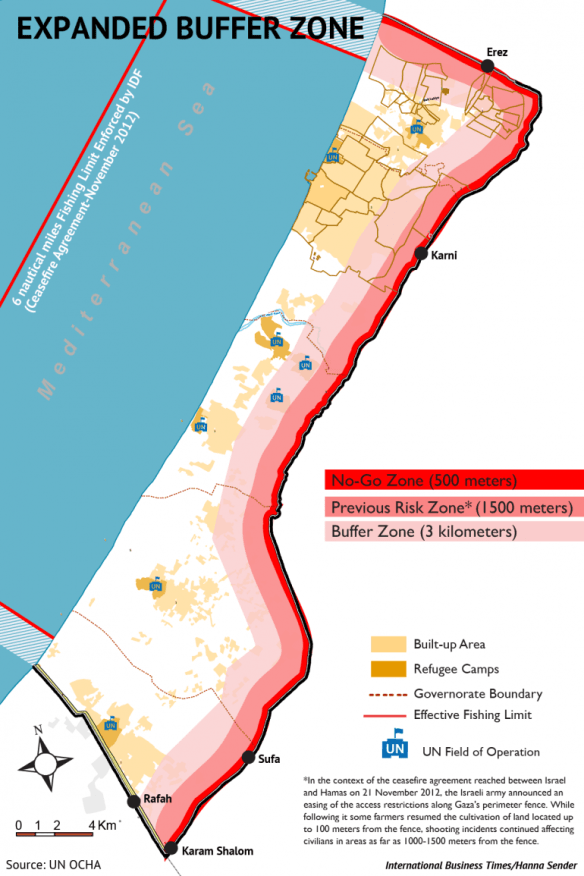

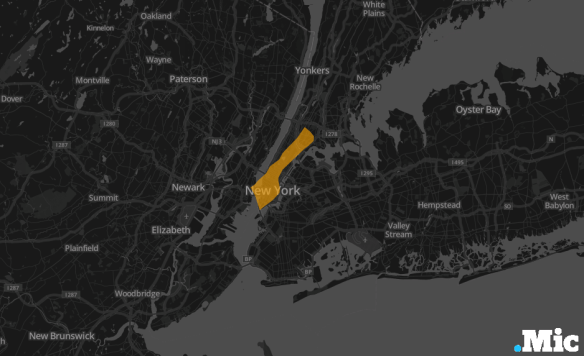

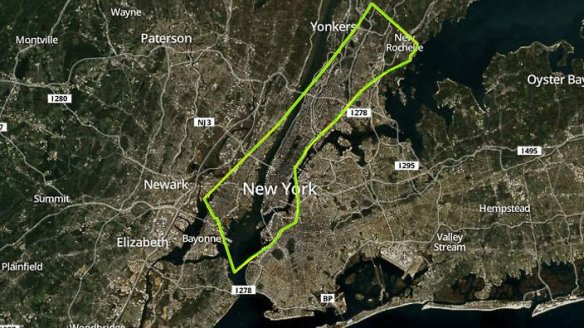

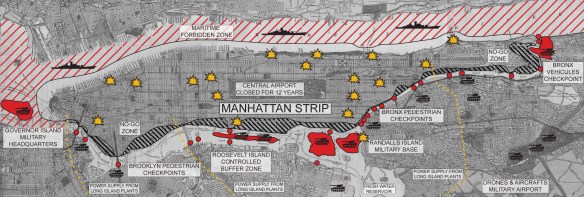

But there’s more. International humanitarian law – no deus ex machina, to be sure, and far from above the fray – not only applies during Israel’s military offensives and operations, including the present catastrophic assault on Gaza, but provides an enduring set of obligations. For as Lisa Hajjar shows in a detailed discussion re-published by Jadaliyya last week, Israel’s attempts to make Gaza into a space of exception – ‘neither sovereign nor occupied’ but sui generis – run foul of the inconvenient fact that Gaza remains under occupation. Israel continues to control Gaza’s airspace and airwaves, its maritime border and its land borders, and determines what (and who) is allowed in or out [see my previous post and map here]. As Richard Falk argues, ‘the entrapment of the Gaza population within closed borders is part of a deliberate Israeli pattern of prolonged collective punishment’ – ‘a grave breach of Article 33 of the Fourth Geneva Convention’ – and one in which the military regime ruling Egypt is now an active and willing accomplice.

So: Gaza 101. Medical equipment and supplies are exempt from the blockade and are allowed through the Karam Abu Salem crossing (after protracted and expensive security checks) but the siege economy of Gaza has been so cruelly and deliberately weakened by Israel that it has been extremely difficult for authorities to pay for them. Their precarious financial position is made worse by direct Israeli intervention in the supply of pharmaceuticals. Corporate Watch reports that

When health services in Gaza purchase drugs from the international market they come into Israel through the port of Ashdod but are not permitted to travel the 35km to Karam Abu Salem directly. Instead they are transported to the Bitunia checkpoint into the West Bank and stored in Ramallah, where a permit is applied for to transport them to Gaza, significantly increasing the length and expense of the journey.

There’s more – much more: you can download the briefing here – but all this explains why Gaza depends so much on humanitarian aid (and, in the past, on medical supplies smuggled in through the tunnels). Earlier this summer Gaza’s medical facilities were facing major shortfalls; 28 per cent of essential drugs and 54 per cent of medical disposables were at zero stock.

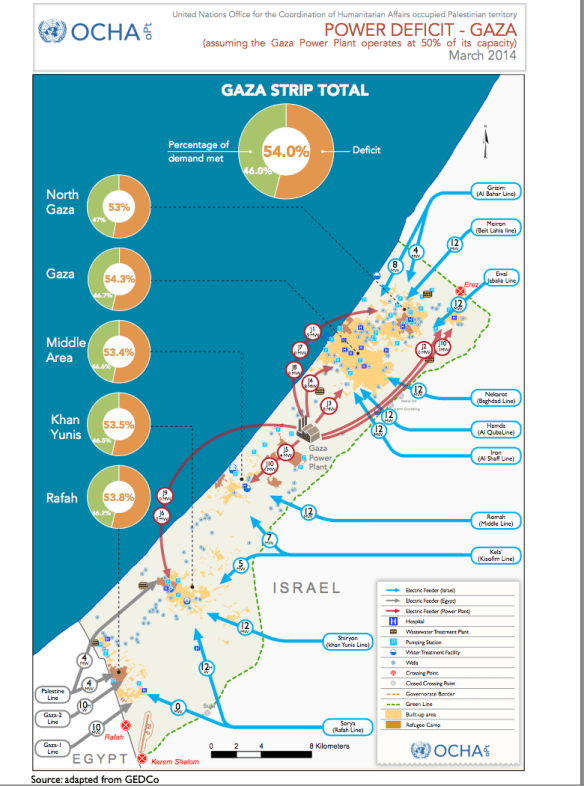

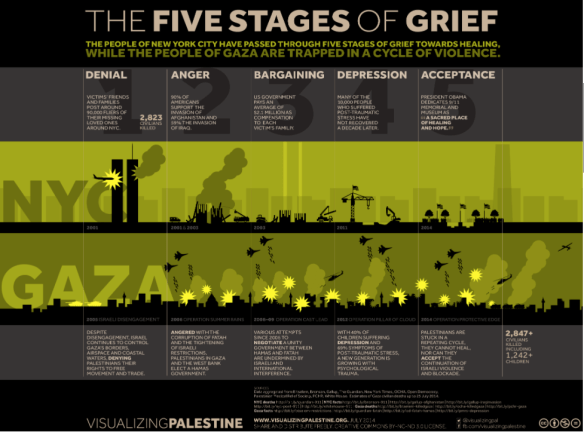

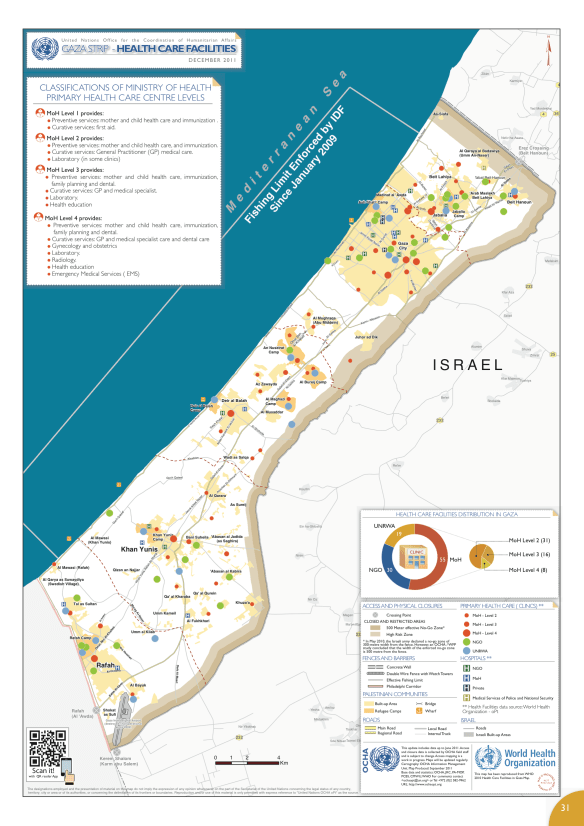

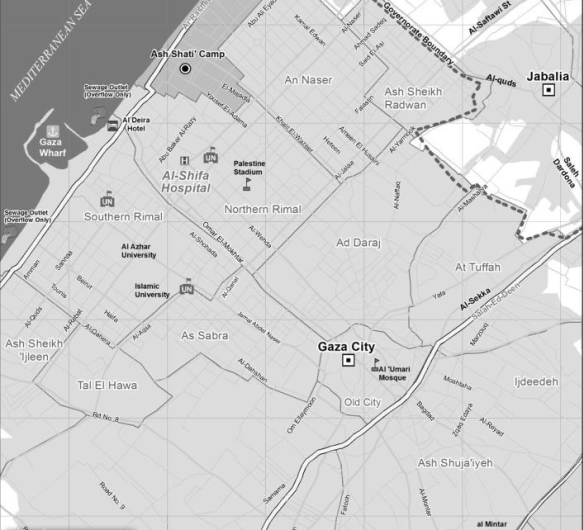

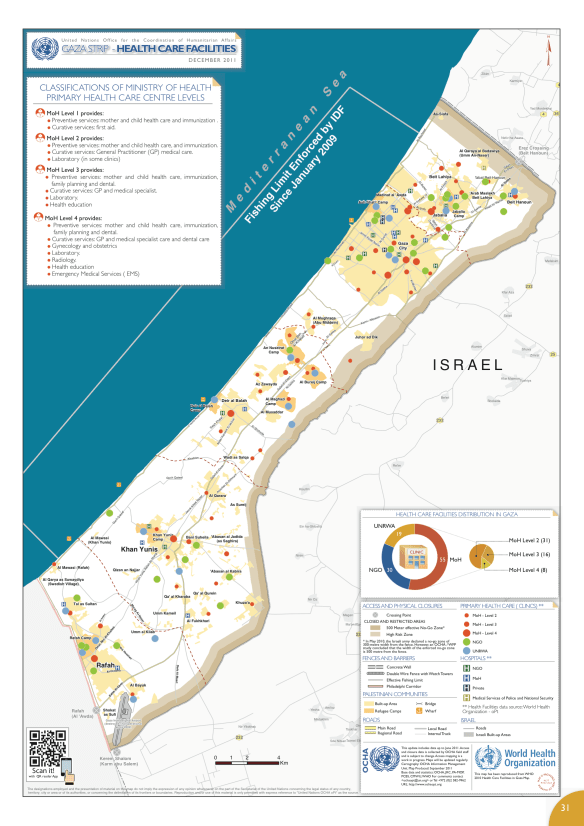

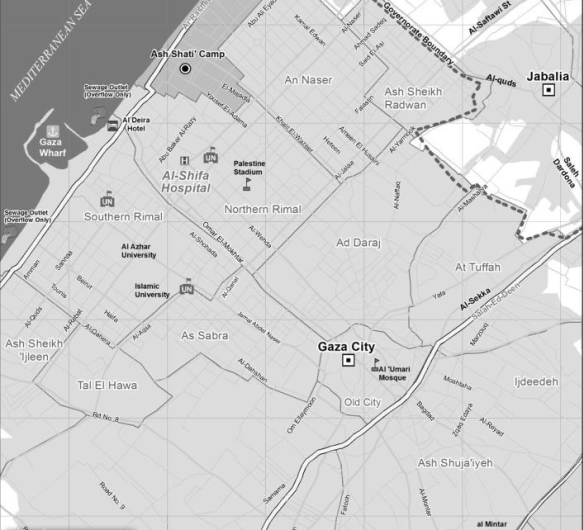

Medical care involves more than bringing in vital supplies and maintaining infrastructure (the map of medical facilities above is taken from the UN’s humanitarian atlas and shows the situation in December 2011; the WHO’s summary of the situation in 2012 is here). Medical care also involves unrestricted access to electricity and clean water; both are compromised in Gaza, and on 1 January 2014 B’Tselem reported a grave deterioration in health care as a result:

‘The siege that Israel has imposed on the Gaza Strip since Hamas took over control of the security apparatus there in June 2007 has greatly harmed Gaza’s health system, which had not functioned well beforehand…. The reduction, and sometimes total stoppage, of the supply of fuel to Gaza for days at a time has led to a decrease in the quality of medical services, reduced use of ambulances, and serious harm to elements needed for proper health, such as clean drinking water and regular removal of solid waste. Currently, some 30 percent of the Gaza Strip’s residents do not receive water on a regular basis.’

In-bound transfers are tightly constrained, but so too are out-bound movements. Seriously ill patients requiring advanced treatment had their access to specialists and hospitals outside Gaza restricted:

In-bound transfers are tightly constrained, but so too are out-bound movements. Seriously ill patients requiring advanced treatment had their access to specialists and hospitals outside Gaza restricted:

‘Israel has cut back on issuing permits to enter the country for the hundreds of patients each month who need immediate life-saving treatment and urgent, advanced treatment unavailable in Gaza. The only crossing open to patients is Erez Crossing, through which Israel allows some of these patients to cross to go to hospitals inside Israel [principally in East Jerusalem], and to treatment facilities in the West Bank, Egypt, and Jordan. Some patients not allowed to cross have referrals to Israeli hospitals or other hospitals. Since Hamas took over control of the Gaza Strip, the number of patients forbidden to leave Gaza “for security reasons” has steadily increased.’

As in the West Bank, Israel has established a labyrinthine system to regulate and limit the mobility of Palestinians even for medical treatment. Last month the World Health Organization explained the system and its consequences (you can find a detailed report with case studies here):

‘In Gaza, patients must submit a permit application at least 10 days in advance of their hospital appointment to allow for Israeli processing. Documents are reviewed first by the health coordinator but final decisions are made by security officials. Permits can be denied for reasons of security, without explanation; decisions are often delayed. In 2013, 40 patients were denied and 1,616 were delayed travel through Erez crossing to access hospitals in East Jerusalem, Israel, the West Bank and Jordan past the time of their scheduled appointment. If a patient loses an appointment they must begin the application process again. Delays interrupt the continuity of medical care and can result in deterioration of patient health. Companions (mandatory for children) must also apply for permits. A parent accompanying a child is sometimes denied a permit, and often both parents, and the family must arrange for a substitute, a process which delays the child’s treatment.’

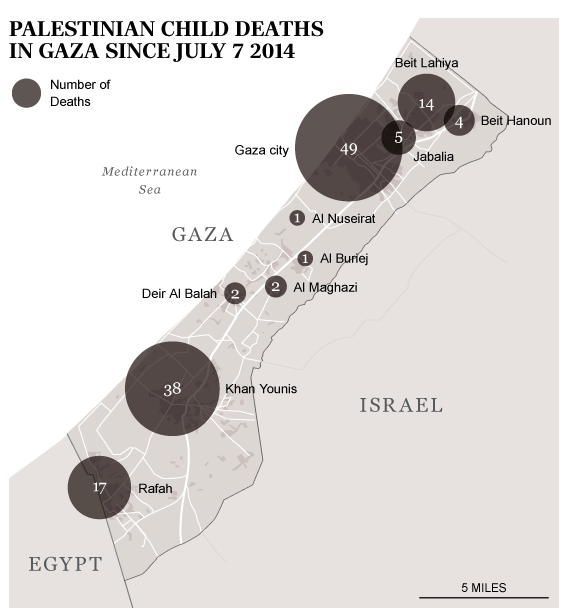

On 17 June Al-Shifa Hospital, the main medical facility in Gaza City (see map below), had already been forced to cancel all elective surgeries and concentrate on emergency treatment. On 3 July it had to restrict treatment to life-saving emergency surgery to conserve its dwindling supplies. All of this, remember, was before the latest Israeli offensive. People have not stopped getting sick or needing urgent treatment for chronic conditions, so the situation has deteriorated dramatically. The care of these patients has been further compromised by the new, desperately urgent imperative to prioritise the treatment of those suffering life-threatening injuries from Israel’s military violence.

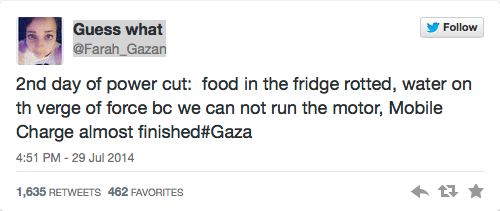

Trauma surgeons emphasise the importance of the ‘golden hour’: the need to provide advanced medical care within 60 minutes of being injured. Before the IDF launched its ground invasion, there were three main sources of injury: blast wounds from missiles, penetrating wounds from artillery grenades and compression injuries from buildings collapsing. But this is only a typology; many patients have multiple injuries. ‘We are not just getting patients with one injury that needs attending,’ said the head of surgery at Al-Shifa, ‘we are getting a patient with his brain coming out of his skull, his chest crushed, and his limbs missing.’ All of these injuries are time-critical and require rapid intervention.  And yet the Ministry of Health reckons that Gaza’s ambulance service is running at 50 per cent capacity as a result of fuel shortages. That figure must have been reduced still further by the number of ambulances that have been hit by Israeli fire (for more on paramedics in Gaza, and the extraordinary risks they run making 20-30 trips or more every day, see here and this report from the Telegraph‘s David Blair here). When CNN reporters visited the dispatch centre at Jerusalem Hospital in Gaza City last Tuesday, they watched a a screen with illuminated numbers recording 193 killed and 1,481 injured and the director of emergency services dispatching available ambulances to the site of the latest air strike (by then, there had already been over 1,000 of them). But the system only works effectively when there is electricity…

And yet the Ministry of Health reckons that Gaza’s ambulance service is running at 50 per cent capacity as a result of fuel shortages. That figure must have been reduced still further by the number of ambulances that have been hit by Israeli fire (for more on paramedics in Gaza, and the extraordinary risks they run making 20-30 trips or more every day, see here and this report from the Telegraph‘s David Blair here). When CNN reporters visited the dispatch centre at Jerusalem Hospital in Gaza City last Tuesday, they watched a a screen with illuminated numbers recording 193 killed and 1,481 injured and the director of emergency services dispatching available ambulances to the site of the latest air strike (by then, there had already been over 1,000 of them). But the system only works effectively when there is electricity…

Power supplies were spasmodic at the best of times (whenever those were); they have been even more seriously disrupted by the air campaign, and since the start of the ground assault Gaza has lost around 90 per cent of its power generating capacity. Nasouh Nazzal reports that many hospitals have been forced to switch to out-dated generators to light buildings and power equipment:

“The power generators in Gaza hospitals are not trusted at all and they can go down any moment. If power goes out, medical services will be basically terminated,” [Dr Nasser Al Qaedrah] said. He stressed that the old-fashioned types of power generators available in Gaza consume huge quantities of diesel, a rare product in the coastal enclave.

On occasion, Norwegian ER surgeon Mads Gilbert told reporters, if the lights go out in the middle of an operation ‘[surgeons] pick up their phones, and they use the light from the screen to illuminate the operation field.’ (He had brought head-lamps with him from Bergen but found they were on Israel’s banned list of ‘dual-use’ goods). As the number of casualties rises, the vast majority of them civilians, so hospitals have been stretched to the limit and beyond. According to Jessica Purkiss, the situation was already desperate a week ago:

“The number of injuries is huge compared to the hospitals’ capacity,” said Fikr Shalltoot, the Gaza program director for Medical Aid for Palestinians, an organization desperately trying to raise funds to procure more supplies. “There are 1,000 hospital beds in the whole of Gaza. An average of 200 injuries are coming to them every day.”

As in so many other contemporary conflicts – Iraq, Libya, Syria – hospitals themselves had already become targets for military violence. For eleven days Al-Wafa Hospital in Shuja’iyeh in eastern Gaza City (see the map above), the only rehabilitation centre serving the occupied territories, was receiving phone calls from the IDF warning them that the building was about to be bombed. [In case you’re impressed by the consideration, think about Paul Woodward‘s observation: ‘I grew up in Britain during the era when the Provisional IRA was conducting a bombing campaign in Northern Ireland and on the mainland. I don’t remember the Provos ever being praised for the fact that they would typically phone the police to issue a warning before their bombs detonated. No one ever dubbed them the most humane terrorist organization in the world.’] The staff refused to evacuate the hospital because their patients were paralysed or unconscious. The Executive Director, Dr Basman Alashi, explained:

‘We’ve been in this place since 1996. We are known to the Israeli government. We are known to the Israeli Health Center and Health Ministry. They have transferred several patients to our hospital for rehabilitations. And we have many success stories of people come for rehabilitation. They come crawling or in a wheelchair; they go out of the hospital walking, and they go back to Israel saying that al-Wafa has done miracle to them. So we are known to them, who we are, what we are. And we are not too far from their border. Our building is not too small. It’s big. It’s about 2,000 square meters. If I stand on the window, I can see the Israelis, and they can see me. So we are not hiding anything in the building. They can see me, and I can see them. And we’ve been here for the last 12 or 15 years, neighbors, next to each other. We have not done any harm to anybody, but we try to save life, to give life, to better life to either an Arab Palestinian or an Israeli Jew.’

But just after 9 p.m. on 17 July shells started falling:

‘… the fourth floor, third floor, second floor. Smoke, fire, dust all over. We lost electricity… luckily, nobody got hurt. Only burning building, smoke inside, dust, ceiling falling, wall broke, electricity cutoff, water is leaking everywhere. So, the hospital became [uninhabitable].’

Seventeen patients were evacuated and transferred to the Sahaba Medical Complex in Gaza City. Sharif Abdel Kouddos takes up the story:

‘The electricity went out, all the windows shattered, the hospital was full of dust, we couldn’t see anything,’ says Aya Abdan, a 16-year-old patient at the hospital who is paraplegic and has cancer in her spinal cord. She is one of the few who can speak.

It is, of course, literally unspeakable. But this was not an isolated incident – still less ‘a mistake’ – and other hospitals have been bombed or shelled. According to the Ministry of Health, 25 health facilities in Gaza have been partially or totally destroyed. Just this morning it was reported that Israeli tanks shelled the al-Aqsa Hospital in Deir al-Balah in central Gaza, killing five and injuring 70 staff and patients. The Guardian reports that ambulances which tried to evacuate patients were forced to turn back by continued shelling. According to Peter Beaumont:

‘”People can’t believe this is happening – that a medical hospital was shelled without the briefest warning. It was already full with patients,” said Fikr Shalltoot, director of programmes at Medical Aid for Palestinians in Gaza city.’

The hospitals that remain in operation are overwhelmed, with doctors making heart-wrenching decisions about who to treat and who to send away, refusing ‘moderately injured patients they normally would have admitted in order to make room for the more seriously wounded.’ Mads Gilbert (centre in the image above) again:

Oh NO! not one more load of tens of maimed and bleeding, we still have lakes of blood on the floor in the ER, piles of dripping, blood-soaked bandages to clear out – oh – the cleaners, everywhere, swiftly shovelling the blood and discarded tissues, hair, clothes,cannulas – the leftovers from death – all taken away…to be prepared again, to be repeated all over. More then 100 cases came to Shifa last 24 hrs. enough for a large well trained hospital with everything, but here – almost nothing: electricity, water, disposables, drugs, OR-tables, instruments, monitors – all rusted and as if taken from museums of yesterdays hospitals.

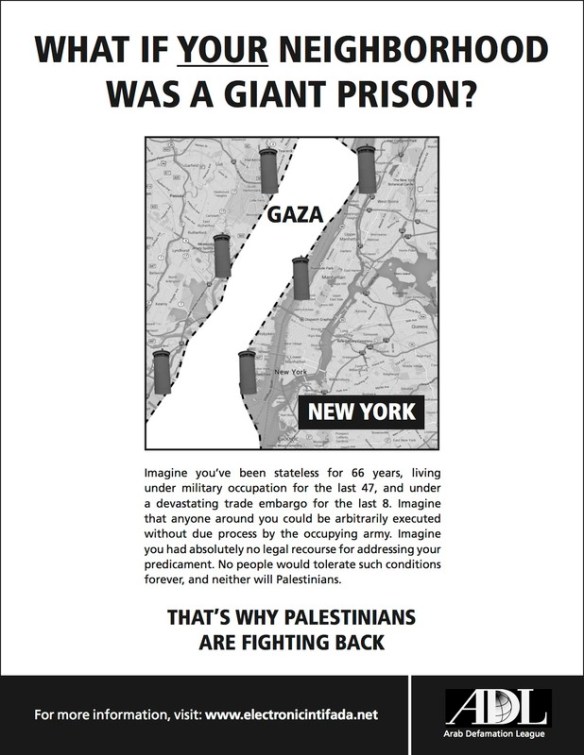

Al-Shifa, where he is working round the clock, has only 11 beds in its ER and just six Operating Rooms. On Saturday night, when the Israeli army devastated the suburb of Shuja’ieyh, its ‘tank shells falling like hot raindrops‘, al-Shifa had to deal with more than 400 injured patients. Al-Shifa is Gaza’s main trauma centre but in other sense Gaza’s trauma is not ‘centred’ at all but is everywhere within its iron walls. Commentators repeatedly describe Gaza as the world’s largest open-air prison – though, given the cruelly calculated deprivation of the means of normal life, concentration camp would be more accurate – but it is also one where the guards routinely kill, wound and hurt the prisoners. The medical geography I’ve sketched here is another way of reading Israel’s bloody ‘map of pain‘. I am sickened by the endless calls for ‘balance’, for ‘both sides’ to do x and y and z, as though this is something other than a desperately unequal struggle: as though every day, month and year the Palestinians have not been losing their land, their lives and their liberties to a brutal, calculating and manipulative occupier. I started this post with an image of a Palestinian ambulance; the photograph below was taken in Shuja’ieyh at the weekend. It too is an image of a Palestinian ambulance.

For updates see here; I fear there will be more to come. In addition to the links in the post above, this short post is also relevant (I’ve received an e-mail asking me if I realised what the initial letters spelled…. Duh.)