Ever since I attended a conference at Nijmegen on Transmobilities I’ve followed the current interest in ‘mobilities’, though from a distance and perhaps in strange ways: but I think that the following study contributes to that debate as well as to quite different preoccupations with the intersections of military geography, medical geography and my current research on woundscapes and ‘trauma geographies‘. Let me know what you think.

Modern trauma response pays close attention to what happens in the ‘platinum ten minutes‘ immediately after injury and treats the ‘golden hour‘ to definitive medical treatment as the standard to which casualty evacuation should adhere. I explored the implications of these metrics for treatment outcomes and survival rates in Afghanistan in ‘the geographies of sixty minutes‘, and as part of my comparative work I’ve been examining the speed of casualty evacuation on the Western Front in the First World War.

The politics of speed

This turns out to be a complicated issue, and one that attracted considerable controversy – both professional and political – throughout the war. There are summaries in Ian Whitehead‘s Doctors in the Great War and in Ana Carden-Coyne‘s The politics of wounds, but some of the sharpest exchanges (in early January 1917) were sparked by a memorandum from Sir Almroth Wright, Consultant Physician to the British Expeditionary Force, criticising what he saw as the preoccupation with rapid evacuation at all costs. His charges were summarily dismissed by General Sir Arthur Sloggett, (right, shown in 1917), the Director-General of Medical Services for the British Expeditionary Force – in angry memoranda and meetings and in acerbic private correspondence – as being entirely without foundation and, indeed, ‘ignorant’ and even ‘stupid’ (see RAMC 365/4 here).

Some front-line medical officers were more perturbed than these exchanges suggest. Surgeon Henry Kaye, for example, addressed the issue in his diary for 24 January 1916, when he sought an explanation for the mortality rates from ‘different classes of wounds’ passing through his casualty clearing station:

‘I should surmise that the only controllable factor is that of transport – ie that a certain percentage of the mortality is due to the transport of seriously wounded men – people are so pleased with the excellence of the transport arrangements (ambulances, trains, and ships) that they forget what a great additional strain any transport imposes on the patients, and are apt to lay approving stress on how quickly they have transported thousands of cases to England, without regarding (or at least mentioning) how many men this express transport has cost their lives. (Diary, Wellcome Institute, RAMC 739/4)

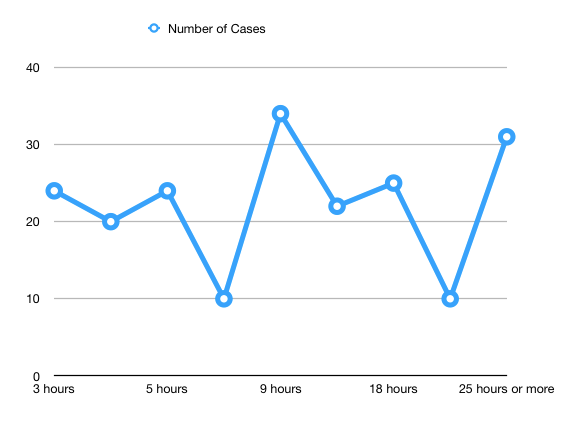

Notice that word ‘surmise’. Given the joined politics of speed it is surprising that there should have been so few detailed studies at the time. In their survey of ‘The development of British surgery at the Front’, published in the British Medical Journal on 2 June 1917, Surgeon-General Sir Anthony Bowlby and Colonel Cuthbert Wallace (Consulting Surgeon to the British Army) showed that out of 200 abdominal cases received at one casualty clearing station (CCS), 164 arrived within 12 hours, another 35 arrived in the next 12 hours, and 31 took over 24 hours to reach the CCS (p. 706).

Another surgeon concluded from these figures that one third of the casualties ‘arrived so late that they had little chance of recovery because of the elapsed time alone’ (Daniel Fiske Jones, ‘The role of the evacuation hospital in the care of the wounded’, Annals of Surgery 68 (2) (1918) 127-132: 130). In a second tabulation Bowlby and Wallace drew on a different sample of abdominal cases which confirmed that 51 per cent of those who arrived at a CCS within 12 hours survived (at least long enough to be transferred to a base hospital on the coast), but for those who took longer than 12 hours the survival rate fell to 33 per cent (p 716).

Another surgeon concluded from these figures that one third of the casualties ‘arrived so late that they had little chance of recovery because of the elapsed time alone’ (Daniel Fiske Jones, ‘The role of the evacuation hospital in the care of the wounded’, Annals of Surgery 68 (2) (1918) 127-132: 130). In a second tabulation Bowlby and Wallace drew on a different sample of abdominal cases which confirmed that 51 per cent of those who arrived at a CCS within 12 hours survived (at least long enough to be transferred to a base hospital on the coast), but for those who took longer than 12 hours the survival rate fell to 33 per cent (p 716).

If nothing else, these figures confirmed the importance of evacuation rates, but their wide dispersion raised a series of important questions. The Australian Army provided two later studies that attended more closely to the geographies of casualty evacuation – and, to some degree, addressed the dispersion in the figures from Bowlby and Wallace – and for the rest of this post I’ll focus on the most detailed of the two.

This related to the evacuation scheme in operation for what became known as the Battle of Menin Road (20-25 September 1917). The image above is Paul Nash‘s celebrated rendering of The Menin Road, which he completed in February 1919. Nash served on the Ypres Salient from February 1917 as a second lieutenant, but a few months later he missed his footing in the dark, fell into a trench and broke a rib. He was evacuated to England, and returned to the Salient in November as an official war artist. (There is a fine discussion of Nash’s art and its relation to the war in Paul Gough‘s A Terrible beauty: British artists in the First World War; for The Menin Road in particular, see pp. 150-62 ).

Third Ypres: the first two phases

The Battle of Menin Road was the third phase of ‘the Third Battle of Ypres’ (July-November 1917) that culminated in the fall of Passchendaele (the name by which the whole series of offensives is often known). The object of the campaign was to seize control of the line of low hills – ‘the ridge’ – running south and east of Ypres.

The first two phases were directed against Pilckem Ridge (31 July to 2 August) and Langemarck (16 to 18 August).

For the medical services there were two pressing problems. The first was the retrieval of casualties by relays of stretcher bearers. The terrain had been reclaimed from marshland by an elaborate system of drains but these were destroyed by savage and relentless artillery bombardments, and Colonel A.G. Butler explained that ‘with the rains – expected in the autumn – the low, flat countryside reverted to primitive morass’ (Official History of the Australian Army Medical Services in the War of 1914-1918, Vol. II: The Western Front, p. 184n). Confounding the Allies’ expectations, however, the rains broke at the end of July. The conditions were frightful, the casualties horrendous, and on 1 August Lt John Warwick Brooke took what turned out to be an iconic photograph that caught the intersection of the two: no fewer than seven bearers struggling to carry a stretcher through the thick, plastering mud-slime near Boesinghe:

That same day Private Walter Williamson was ordered to a ruined building – he had no idea what it used to be – where his Regimental Medical Officer had established an aid post:

The place had simply been battered with shell fire and the road ploughed up, but this had now settled down to one horrible level surface of water and oozing mud….

Stretchers with their pitiful burdens were brought out from the inner recesses of the ruins, and we were detailed each four to a stretcher … containing a badly wounded lad who was only conscious enough to feebly moan to us to put him straight in the boat [to ‘Blighty’]. We heaved the stretcher to our shoulders, and started off that long remembered journey down the St Julien road. In addition to being weak and tired, our uneven heights made carrying difficult, and it must have been torture for the poor occupant of the stretcher. In the best places, the road was nearly knee deep in mud, and shell holes could not be located except by testing each foothold. Planks had been put down in places where the whole width of the road had been blown up, but these were now floating aimlessly about, and any attempt to use them would have resulted in a spill, and hurling our burden into the mud. Rain still poured down unceasingly and the road was being shelled viciously. We could not well duck at the shells, with a badly wounded man dependent on steady shoulders, and all we could do was to plod through and trust to good luck…

The road was a gruesome nightmare, bodies lay in the mud all along the road and burial parties were busy collecting them as best they could. Dead mules, horses, wrecked guns, limbers and all the terrible debris of battle lay in the mud. We were getting now, that we could not carry the stretcher more than a hundred yards at a stretch, and each time we rested, we found it more difficult to heave it up again, but we plodded along with red hot shoulders and cracking backs, sometimes having to get nearly waist deep to find a foothold across some huge hole that stretched from one side of the road to the other’ (Doreen Priddey (ed), A Tommy at Ypres: Walter’s War).

They eventually succeeded in delivering the poor man to a motor ambulance, which would have taken him to a dressing station or a casualty clearing station.

The walking wounded didn’t fare much better, and the distinction between them and stretcher cases was by no means clear-cut or constant, as the experience of Private Alfred Warsop makes horribly clear. Hit by shrapnel in the jaw, arm and chest, he passed out and when he came round ‘a doctor was just finishing bandaging me up and he said, “Get a stretcher for this man as soon as you can.”‘ Realising there were unlikely to be enough bearers available to carry him through the mud, he decided to walk out:

‘I persuaded a first aid man to put his hand in the middle of my back and hoist me on my feet. I tottered out determined to get down to the Menin Road or die in the attempt –on this occasion no idle phrase. It was all slippery mud, shell holes and trenches. I soon found that I had lost nearly all sense of balance with both arms useless. No doubt I was able to make that journey because I was suffering from shock and not feeling things as you normally would’ (in Steel and Hart, Passchendaele: the sacrificial ground)

Similarly, Gunner Walter Legg recalled coming to the aid of a badly wounded young soldier – carrying him to a shell hole and applying a field dressing, then helping him stumble to the aid post:

‘I remember vividly that with each step he took, blood oozed out on to the loose loop of his braces and fell drop by drop on his trousers. From where we were I could see the forward dressing station about a quarter of a mile to the rear… We managed to make progress a few yards at a time. We’d shelter for a bit in a shell-hole, and then if the shelling seemed to be easing up we’d crawl into the next one and wait there for a bit, then try and get to the next one a yard or two away. After a couple of hours … we’d only gone thirty or forty yards…

It took us ten hours to cover that quarter-mile to the dressing station, and when we got there we were absolutely drenched to the skin and thick with mud’ (in Lynn MacDonald, They called it Passchendaele).

The second problem emerged as soon as the injured reached a road: their transfer to a main dressing station or casualty clearing station was often slowed because the roads were in a poor condition, many of them full of craters and badly degraded by the constant traffic of convoys and marching columns, but also because the ambulances had to struggle against the flow, yielding to fresh troops, ammunition and supplies moving in the opposite direction. The priority was clear. ‘The conditions of warfare demand … that wounded men shall be got out of the war,’ wrote one senior medical officer, so that supplies of reinforcements, ammunition and food to the fighting line are not interfered with’ (Col. H. M. W. Gray, ‘Surgical treatment of wounded men at advanced units’, New York Medical Journal 107 (1917)).

To regulate the flow, elaborate arrangements were made to control the direction of traffic, sometimes with special routes designated for ambulances. The map below shows the traffic circuits established by the Fifth Army around Ypres by 27 July 1917:

[Roads shown in red could be used in both directions; roads shown in blue only in the direction indicated; roads not coloured were not to be used by lorries and could be used by ambulances or light traffic; there was ‘no restriction placed on Motor Cars containing Officers on duty’.]

Despite the slow journeys faced by wounded soldiers, the casualty clearing stations were hard pressed to keep up with the tide of injured bodies. This was particularly true for those fed by by broad-gauge train from dressing stations in Vlamertinghe and Ypres. That was how most of the nominally ‘walking wounded’ arrived at the CCSs at Remy Siding on the night of 31 July/1 August. ‘They consequently arrived in very large batches,’ Major-General Sir W.G. Macpherson explained, ‘instead of coming down in small numbers at a time by lorries and charabancs.’ This overwhelmed the CCSs and delayed the departure of ambulance trains to the base hospitals, which could not leave until the casualties had been cleared, and the congestion was compounded because the trains bringing them in used the same siding as the ambulance trains waiting to come up and load: eight of them were scheduled in the first 24 hours (Medical Services, General History, Vol. III, pp. 160-1).

On that first day US surgeon George Crile, working at No 17 British CCS at Remy Siding, described how

‘The stream of wounded began to increase in volume, slowly at first, then rapidly, until the entire Remy Siding was swamped. By the night of August first, every bed, every aisle, every tent, every inch of floor space was occupied by stretchers – then the rows of stretchers spread out over the lawn, around the huts, flowing out towards the railway…

The operating rooms ran day and night without ceasing. Teams worked steadily for twelve hours on, then twelve hours off, relieving each other like night–day–night shifts. There passed through the Remy Siding group of [three] CCSs over ten thousand wounded in the first forty-eight hours. I had two hundred deaths in one night in my service. The seriously wounded piled up so fast that nothing could be done with them, so I told the sister to administer as near an overdose of morphine as was possible to keep them alive but free of suffering’ (Autobiography, pp. 301-2).

It was the same everywhere. Here is another American surgeon, Harvey Cushing, writing in his journal at No 46 British CCS near Proven at 0230 the next morning:

Pouring cats and dogs all day – also pouring cold and shivering wounded, covered with mud and blood…. The pre-operation room is still crowded – one can’t possibly keep up with them; and the un-systematic way things are run drives one frantic. The news, too, is very bad. The greatest battle of history is floundering up to its middle in a morass, and the guns have sunk even deeper than that. Gott mit uns was certainly true for the enemy this time.

Operating from 8.30 a.m. one day till 2.00 a.m. the next; standing in a pair of rubber boots, and periodically full of tea as a stimulant, is not healthy. It’s an awful business, probably the worst possible training in surgery for a young man, and ruinous for the carefully acquired technique of an oldster. Something over 2000 wounded have passed, so far, through this one C.C.S. There are fifteen similar stations behind the battle front (From a surgeon’s journal, p. 175).

(In his biography of Cushing, Michael Bliss remarked that having such a great surgeon perform brain surgery at a CCS – with exquisite care and meticulous attention to detail – was ‘like a master chef working at McDonald’s’, but Crile told Bowlby he was a model technician and advised him to organise the other surgical teams to handle the overflow).

The combined toll of these two phases in July and August was sobering, but they advanced the line to the east of Hooge (or, more accurately, to what was left of it: ‘even the road was untraceable,’ Charles Bean explains, ‘and the village site was only marked by a cluster of mine craters’ (Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-18, Vol. IV: The A.I.F. in France [sic]: 1917). With that, the offensive appeared to have ground to a halt – literally so – and the German High Command concluded that Third Ypres was over.

The third phase: Menin Road

They were mistaken. On 25 August British field command had been transferred to Lt General Herbert Plumer who devised a new, more measured plan for the third phase, which involved four short steps across a narrow front, separated by breaks to bring up the guns and supplies. It would be spearheaded by Australian and New Zealand troops, with British and South African support.

Plumer took the next three weeks to prepare the ground for the first of his graduated steps, which was the Battle of Menin Road. The road had been what one NCO called ‘the artery of the battlefield’ during the limited advance of the summer (Corporal J. Pincombe, in Lynn MacDonald, They called it Passchendaele, p. 144), and it remained a live fire zone. ‘They had to keep the Menin Road open,’ recalled one driver with the Royal Artillery,

‘because it was the only way you could get up to that sector with horses and limbers, and it was shelled day and night. The Germans had their guns registered on it to a T, and the engineers had to keep filling up the shell-holes … and keep the traffic going’ (Driver J. McPherson, in Lynn MacDonald, They called it Passchendaele, p. 177)

Paul Ham describes the scale of the preparations:

Plumer packed every ounce of energy and action into those few weeks. Within the next seventeen days, 156 trainloads carrying 54,572 tons of matériel arrived at the railheads, all of which had to be trucked, entrained, dragged or carried on mule-back to the front. Light tramways were hastily reconstructed and roads rebuilt out of wooden planks. Shell holes were filled in and stamped down; gun emplacements firmly laid; telephone lines unrolled and buried; rations and medical supplies prepared and brought forward –all of which proceeded within range of German shellfire. Miles of duckboards were laid, latticing the drying plain, connecting little islands and ridges of high ground in the hardening mud. The men trained all day, rehearsing new platoon tactics, pillbox flanking manoeuvres and how to coordinate their advance with the creeping barrage, worked out to mathematical certainty (Ham, Passchendaele, p. 245).

In the interval the ground dried out and the terrain ‘changed from a morass into a desert’ (Bean, AIF, p. 748). But it was still immensely difficult terrain, riddled with shell holes and all the hideous detritus of war. In a letter written from Vlamertinghe on 17 September Hugh Quigley painted a bleak picture:

‘The country resembles a sewage-heap more than anything else, pitted with shell holes of every conceivable size, and filled to the brim with green, slimy water, above which a blackened arm or leg might project. It becomes a matter of great skill picking a way across such a network of death traps, for drowning is almost certain in one of them (in Martin Marix Evans, Passchendaele: the hollow victory).

The next map shows the line two days later, on 19 September – the night before the new offensive began:

Plumer’s plan called for clockwork precision. The infantry were to advance behind a devastating rolling barrage, whose opening curtain would fall just 150 yards (130 metres) in front of the troops; after three minutes, as the troops moved up, it would roll forward at 100 yards every four minutes for the first 200 yards, and then at a rate of 100 yards every six minutes until the first objective, the Red Line, was reached: a distance of 750 metres. The barrage would then halt for 45 minutes before rolling on at 100 yards every eight minutes until the Blue Line was reached: a further 400 metres. After a pause for two hours the barrage would advance again at the same rate to the Green Line, the last objective of the day: a further 200 metres.

The slow rate of advance – compared to other rolling barrages – and the short distances eased the difficulty of picking passages through the pock-marked terrain, but there was little room for error or misstep. Observing a rehearsal, Captain A.M. McGrigor recorded that

‘it did bring home to one how appallingly mechanical everything is now, and how every man must conform to the advance of the barrage. Initiative and dash must to a certain extent be fettered as every forward movement is worked out so carefully and mathematically’ (in Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson, Passchendaele: the untold story)

Planning for casualties

These precise timings were complemented by similar calculations in the accompanying plan for medical provision drawn up by General Arthur Sloggett, perhaps still smarting from and certainly still contemptuous of Wright’s criticisms (above), and Surgeon-General G.B.M. Skinner (Fifth Army), which was intended to remove the extraordinary frictions that had bedevilled the evacuation chain during the summer. Butler makes the parallel explicit: ‘The machinery for clearing our own casualties had to move with the same clockwork precision as that designed by us to create them in the enemy’ (Australian Army Medical Services, p. 211).

Their plan was guided by two imperatives.

(1) Casualty Clearing Stations The first was to bring casualty clearing stations as close to the line as possible. This entailed a continuation of the system that had emerged during the summer.

In July and August three CCSs had been deployed just five miles from the front at a railway siding at Brandhoek, located just off the main Ypres-Poperinghe road, and offering direct rail access for hospital trains to the base hospitals at Boulogne and Calais.

Sister Kate Luard was thrilled with the experiment, writing in her diary that ‘we … shall be near enough to the line to get them from the dressing stations direct, without long journey and waits which is what the C.C.S.’s are out to prevent nowadays.’ She arrived at Brandhoek on 27 July, and while she was delighted at what she found (not least because she would be working at a specialist CCS for the treatment of abdominal wounds) she again emphasised the experimental nature of the location:

The hospital had only been pitched since last Saturday and it was already splendid. This venture so close to the Line is of the nature of an experiment in life-saving, to reduce the mortality rate from abdominal and chest wounds. Their chance of life depends (except where the injuries are such as to be beyond any hope of recovery) mainly on the length of time between the injury and the operation. As modern Field Surgery can now be carried out under conditions of perfect asepsis, the sooner the infection always introduced into every wound with the missile is dealt with, and the internal repairs carried out, the more chance the soldier has of life. Hence this Advanced Abdominal Centre, to which all abdominal and chest wounds are taken from a large attacking area, instead of going on with the rest to the C.C.S.’ s six miles back….

Sir Anthony Bowlby turned up later. ‘How d’you like the site this time? Front pew, what? front row dress-circle.’ It is his pet scheme getting the operations done up here within an hour or two of getting hit, instead of farther back or at the Base. That is why our 30 Medical Officers include the largest collection of F.R.C.S.’ s [Fellows of the Royal College of Surgeons] ever collected at any Hospital in France before, at Base or Front, twelve operating Surgeons with Theatre Teams working on eight tables continuously for the 24 hours, with 16 hours on and 8 off.

The location was ideal for rapid medical treatment; but as was often the case, the railway line also made it an optimal location for artillery batteries and ammunition dumps. When Harvey Cushing visited Brandhoek two days later he observed that ‘the three CCSs were ‘necessarily alongside both road and railway, for hospitals and ammunition dumps must compete for sites of the same kind – and hence they are likely to be heavily shelled.’ And as Colonel A.G. Butler confirmed in the official history of the Australian Army’s medical services, ‘the site had the grave disadvantage that some British 15-inch guns were near by, and huge supply and ammunition dumps covered the adjoining area’ – all, as he concedes, ‘legitimate and obvious targets for German artillery’ (Australian Army Medical Services, p. 188).

It was quiet when Bowlby and Cushing visited, but the medical staff did not have long to wait before their fears were confirmed. On 30 July Luard wrote:

‘Soon after 10 o’clock this morning [the Germans] began putting over high explosive. Everyone had to put on tin-hats and carry on. He kept it up all the morning with vicious screams. They burst on two sides of us, not 50 yards away – no direct hits on to us but streams of shrapnel, which were quite hot when you picked them up. No one was hurt, which was lucky, and they came everywhere, even through our Canvas Huts in our quarters. Luckily we were so frantically busy that it was easier to pay less attention to it. The patients who were well enough to realise that they were not still on the field called it ‘a dirty trick.’

It is doubtful that the CCSs were the intended target (and they were treating many German prisoners). Rather, as Sister May Tilton recorded, the area was ‘a huge city of canvas, batteries and ammunition dumps’ – the question of co-location constantly dogged casualty clearing stations and base hospitals alike (see here) – and throughout the next month Brandhoek was subjected to regular shelling and air raids.

On 2 August Luard wrote that ‘it made one realise how far up we are to have streams of shells crossing over our heads’ – from the German lines and from the British batteries around Brandhoek – but the danger was also a more proximate one. Here she is a few days later:

There is a cheery little Military Decauville Railway for ammunition only, running immediately between our Compound and the main Duck Walk cutting our Hospital in two, and you are always having to wait to cross the rails while a series of baby trains puff through loaded to the teeth with shells, or coming back with empty cases.

The attacks intensified, and on 14 August Tilton wrote that last night

‘No one slept, day or night staff. Our bell tents were dugouts. They had lowered us considerably and sandbagged the outsides so heavily, we felt quite comfortable. It needed a direct hit to get us…’

At 10.30 pm ‘the Gothas [bombers] were over’ and ‘shells were bursting quite close’, but the British batteries responded with alacrity: “Big Bob” [the 15-inch guns] set our tents rocking and vibrating with his fierce and mighty roar.’

On 18 August Luard was outraged at German attacks on hospitals – but she was specifically referring to those in the rear:

He [‘Fritz’] played about all night till daylight. There were several of him. He went to C.C.S.’ s behind us. At one he wounded three Sisters and blew their cook-boy to pieces. The Sisters went to the Base by Ambulance Train this morning. At the other he wounded six Medical Officers among other casualties. A dirty trick, because he has maps and knows which are hospitals back there. Here we are in a continuous line of camps, batteries, dumps, etc., and he may not know.

That last sentence was crucial, but the CCSs at Brandhoek were subjected to sustained shelling throughout the day on 21 August, and two days later Sister Elsie Grant wrote to her sister from Brandhoek with no hesitation in assigning blame:

‘We have been shelled out three times but this last time was too dreadful. Those brutal Germans deliberately shell our hospital with all our poor helpless boys but really God was good to us we had four killed but it was just miraculous that there were not dozens killed. Of course we (the sisters) were put into dugouts as soon as the shelling got bad but I can’t tell you how cruel it was to leave those poor helpless patients. In a few hours the whole hospital was evacuated & one consolation we saw our last patient carried out before we were sent away.’

Two of the CCSs were immediately moved back to ‘Nine Elms‘ (below), five miles behind Poperinghe, while Luard’s remained to provide treatment for walking wounded until it too was evacuated in early September.

Throughout these attacks and dispersals, the CCSs had continued to work at full capacity to deal with the thousands of casualties. But by September the closest CCSs for the Battle of Menin Road were now all much further back: at Nine Elms, at Remy Siding, and three other groups near Proven known in the British Army’s ironic Flemglish as ‘Mendinghem’, ‘Dozinghem’ and ‘Bandaghem’. Cushing explained:

The place… is called “Mendinghem.” This was originally a joke and was to have been “Endinghem”; but this on second thought was changed as being too much even for the Tommy. The army has a professional name maker, I may add. Mendinghem is already on the printed maps and there is in this district a “Bandagehem” and “Dosinghem” which I have not located as yet.

They are all all shown on this map:

These relocations did not end the raids, and the official British medical history by Major-General W.G. Macpherson includes a detailed list of enemy shelling and bombing of CCSs from 3 July to 29 October (pp. 163-4); Mendinghem and Dozinghem were repeatedly attacked. According to Cushing, the staff at Dozinghem were particular upset ‘because General Skinner had ordered an electric Red Cross to be shown at night – a good mark to shoot at’ (A surgeon’s journal, p. 193). In fact, Macpherson concluded that these attacks

These relocations did not end the raids, and the official British medical history by Major-General W.G. Macpherson includes a detailed list of enemy shelling and bombing of CCSs from 3 July to 29 October (pp. 163-4); Mendinghem and Dozinghem were repeatedly attacked. According to Cushing, the staff at Dozinghem were particular upset ‘because General Skinner had ordered an electric Red Cross to be shown at night – a good mark to shoot at’ (A surgeon’s journal, p. 193). In fact, Macpherson concluded that these attacks

‘were of so exceptional a character as to give rise to the belief that they were deliberate. The medical units were indicated by the usual red cross signs on roofs of huts, and also on large squares on the ground such as could be seen by aircraft. The positions of casualty clearing stations had also been notified to the enemy’ (Medical Services, General History, Vol. III, p. 162).

Macpherson, wise after the event, commented that Brandhoek ‘had always been regarded as too far forward’ – he claimed the CCSs were only there at the insistence of the Fifth Army commander and his Director of Medical Services – and concluded that the whole affair showed ‘that a journey of twenty minutes to half-an-hour to a more secure locality farther back is not likely to be so great a risk to the patient as his retention in a more forward position which is in danger of being shelled by the enemy’ (p. 156).

(2) Direct evacuation The retreat of the forward CCSs placed a still greater premium on the second imperative, which involved another experiment, a concerted attempt to expedite the movement of the wounded to the rear. In practice, this resolved into marking and co-ordinating evacuation routes for bearer teams and ambulances, minimising treatment at all intermediate dressing stations (even the administration of anti-tetanus serum had to wait until a casualty arrived at the CCS), and separating casualty streams from the Advanced Dressing Stations (ADS) into the three circuits shown on the diagram below:

I’ve seen many similar maps – the war diaries of Field Ambulances are full of them, either superimposed over or based on trench maps, and Regimental Medical Officers were accustomed to draw up their own annotated sketch maps showing the location of aid posts and the routes to be followed by the regimental stretcher bearers – but this one is unusual because it extends beyond the immediate recovery zone and (following directly from the emphasis on direct evacuation) includes a series of timings from the front line all the way back to the CCSs at Remy Siding.

As the map shows, ‘walking wounded’ made their own way to the collecting point at Hooge on the Menin Road and then (by ambulance or light rail if space were available, otherwise on foot) to the ADS designated for them in Ypres.

The more seriously wounded were brought to the same collecting point by regimental stretcher bearers in a series of relays; this was estimated to take between 10 and 40 minutes during the day and around 60 minutes at night. The casualties were then transferred by motor ambulance to the ADS for stretcher cases, just across the road from the ADS for walking wounded (below).

The location of the two ADSs made sound logistical sense, but they were uncomfortably close to heavy artillery batteries and naval guns and were repeatedly shelled. Together the ADSs acted as the hub for what the Medical History calls the ‘elaborately detailed’ system of onward evacuation (Australian Army Medical Services, p. 202):

- Those who could withstand the journey – a further 80-120 minutes, according to the map – followed Circuit A (‘long distance’) to the CCSs at Remy Siding; 58 per cent of stretcher cases followed this route.

- Those suffering from shock, gas or haemorrhage followed Circuit B (‘short distance’) to the Main Dressing Station at Dickebusch, a journey of 20-30 minutes; 27 per cent of stretcher cases followed this route.

- Those who needed immediate surgery were sent direct to Remy on Circuit C – a journey of 90 minutes – and 15 per cent followed this route.

It’s not clear how these timings were established: they were almost certainly estimates written in to the plan rather than observations after the event. But there is a clear consensus that, if that were the case, the estimates were realised and according to official historian Charles Bean the first day of the battle itself ‘went almost precisely in accordance with plan’ (AIF in France, p. 761).

The Battle of Menin Road

It started to drizzle during the evening of 19 September, and when it changed into steady rain and the dust turned back into mud there were understandable jitters. But shortly after midnight the rain eased and Plumer was determined to press on. Zero hour was 0540 on 20 September, when ‘the whole of the British artillery and machine-guns, breaking in with the suddenness of a great orchestra, gave the signal for the attack to start’ (Bean, AIF, p. 757). Frank Hurley, the Australian Official Photographer, was there to capture the scene, but his words (Diary, pp. 87-8) are as evocative as his photographs:

We were just walking along the Menin road in the twilight, near Hellfire Corner, when our barrage began. Simultaneously from a thousand guns, & promptly on the tick of five, there belched a blinding sheet of flame: & the roar – Nothing I have heard in this world or can in the next could possibly approach its equal. The firing was so continuous that it resembled the beating of an army of great drums. No sight could be more impressive than walking along this infamous shell swept road, to the chorus of the deep bass booming of the drum fire, & the screaming shriek of thousands of shells. It was great, stupendous & awesome.

The walking wounded were the first to pass through the collecting post, followed by the stretcher cases.

There were delays in moving them down the Menin Road (below; the first photograph is another Hurley), but according to the officer commanding the 3rd Field Ambulance these were ‘due to the amount of traffic – ammunition limbers, lorries, etc. – which held up the ambulance waggons.’ There was ‘practically no delay by enemy shelling on the road, which we all so greatly feared.’ (They were wise to do so; the reprieve was short-lived and the German batteries soon re-registered on the Road).

There were delays in moving them down the Menin Road (below; the first photograph is another Hurley), but according to the officer commanding the 3rd Field Ambulance these were ‘due to the amount of traffic – ammunition limbers, lorries, etc. – which held up the ambulance waggons.’ There was ‘practically no delay by enemy shelling on the road, which we all so greatly feared.’ (They were wise to do so; the reprieve was short-lived and the German batteries soon re-registered on the Road).

The Red Line was secured at 0611.

By 0700 the first walking wounded started to arrive at their Advanced Dressing Station, followed by the first stretcher cases at 0900 (again, the photographs below are by Hurley):

The Blue Line was secured at 0815 and the Green Line at 1015.

At first the light railway was used to clear cases from the ADSs to the CCS, but the service was disrupted (in part by enemy shelling and part by a backlog at Remy) and lorries took over until the trains were restored by mid-morning. In the first 24 hours 2,200 Australian and 1,000 British wounded passed through the twin ADSs; the proportion of walking wounded to stretcher-cases was roughly 3 : 1 (though, as I’ve noted previously, the distinction between the two was by no means hard and fast) (Australian Army Medical Services, pp. 208-9).

Further down the evacuation chain at the CCSs at Remy Siding casualties started to arrive ‘so rapidly as to cause some embarrassment’ but the stations started to take in by turns – a standard practice – and this successfully relieved the congestion: thereafter casualties arrived in a steady stream.

Meanwhile stretcher bearers were moving up as the line advanced and new relay posts were being established. From 1800 a light railway ferried the walking wounded directly from Birr Crossroads via the MDS to the CCS.

The official history has nothing but praise for the execution of Plumer’s plan, and Bean attributed the success of the first day to the artillery: ‘The advancing barrage won the ground; the infantry merely occupied it’ ( AIF, p. 761). It is perfectly true that the German troops fell back under the sustained barrage, and that their counter-attacks were all repulsed, but this one-liner does an extraordinary disservice to the infantry that ploughed forward.

The medical history tells a more cautious story, and Butler emphasised that ‘throughout the day shell-fire was severe in the captured area’ – a situation with awful consequences for the troops and for the regimental stretcher-bearers who came to their aid.

Again Frank Hurley captures the dreadful scene that same day with a visceral immediacy:

I pushed on up the duck board track to Stirling Castle – a mound of powdered brick [below] and from where there is to be had a magnificent panorama of the battlefield. The way was gruesome & awful beyond words. The ground had been recently heavily shelled by the Boche & the dead and wounded lay about everywhere. About here the ground had the appearance of having been ploughed by a great canal excavator, & then reploughed & turned over and over again. Last nights shower too made it a quagmire; & through this the wounded had to drag themselves, & those mortally wounded pass out their young lives.

The shells shrieked in an ecstasy overhead, & the deep boom of artillery sounded like a triumphant drum roll. Those murderous weapons the machine guns maintained their endless clatter, as if a million hands were encoring & applauding the brilliant victory of our countrymen. It was ineffably grand & terrible, & yet one felt subconsciously safe in spite of the shell burst & splinters & the ungodly wanton carnage going on around.

] I saw a horrible sight take place within about 20 yards of me. Boche prisoners were carrying one of our wounded in to the dressing station, when one of the enemy’s own shells struck the group. All were almost instantly killed, three being blown to atoms. Another shell killed four & I saw them die, frightfully mutilated in the deep slime of a shell crater. How ever anyone escapes being hit by the showers of flying metal is incomprehensible. The battlefield on which we won an advance of 1500 yards, was littered with bits of men, our own & Boche & literally drenched with blood (Diary, pp. 91-3 ).

And this, as Paul Ham reminds us, ‘was a battle that had gone well, in which everything had proceeded according to the plan’ (Passchendaele, p. 305). The total British and Dominion casualties on that one day were around 21,000, expended in order to advance one and a half miles and to hold an area of 5.5 square miles.

Hurley recognised the extraordinary sacrifices made by those bringing in the wounded (above), and that same evening he wrote of his admiration for ‘the magnificent work of the stretcher bearers who go out in the thick of the strife to succour the wounded.’ Many of them were killed or injured, and by the end of the day one subaltern with the 3rd Field Ambulance reported that he had

‘ended up with four fit squads, fifteen men wounded, five missing and five worn out. Bearers all thoroughly done up.’

Not surprisingly, it was difficult for the bearers to find (let alone recover) all those who had been wounded. On 28 September Harvey Cushing was operating on a British soldier at Mendinghem and asked him his division and regiment:

“Oxford Bucks; 20th Division, sir.”

“How can that be, they went over on the 20th, a week ago?”

“I went over with ’em, sir.”

He actually did, and has been lying for a week in a shell hole, until, during the attack of yesterday, someone found him. He said he had eaten nothing, for his bully beef went “agin” him and he wasn’t hungry — indeed thought he had been out of his head for two or three of the days. Then when it got dark he used to holler, but no one came….

He doesn’t seem to think his escapade anything out of the ordinary … I asked him if he was in the barrage of yesterday morning and whether he knew there was an offensive under way. No, he just heard a terrible rattle and crawled up to the edge of his shell hole and waved his hand: some stretcher-bearers came along and took him away—that’s all he knows (A surgeon’s journal, p. 214).

You might think he was an outlier to all those accounts of rapid evacuation, physically and statistically, but he plainly wasn’t the only one. And as the phased advance continued, so conditions deteriorated and the dangers increased.

By 4 October the rains returned with a vengeance, and as the battle for Passchendaele ground on and the toll mounted so one nightmare day became indistinguishable from the next. The carries became longer and longer; bearer parties found it harder and harder to find their way in a landscape (or what Samuel Hynes calls an anti-landscape) devoid of any permanent markers; even those areas stitched together by duckboards became dangerously slippery:

From 8 to 11 October, one medical officer reported,

‘the work was so heavy that for a large part of the time 6 men had to carry one stretcher – 8 and even 12 men were used in parts. Under these conditions the stretcher-bearers rapidly became exhausted, and absolutely so after 24 hours’ work. Usually they were relieved after 24 hours, but owing to the universal shortage some 36 and even 48 hour shifts were done. About 200 bearers (ambulance and infantry) were continually at work’ (Australian Army Medical Services, p. 234).

It’s not my purpose here to chart the unfolding geography of casualty evacuation in any detail – it was modelled on the plan for Menin Road but constantly adapted to the changing circumstances: ‘the medical scheme for each battle was an extension, at most a variant, of that for the preceding one; they were built up, as the line advanced, in the general “arrangements” described’ above: Australian Army Medical Services, p. 212) – but one stretcher-bearer epitomises the wrenching experience as well as anybody. Frederick Noyes was with the 5th Canadian Field Ambulance, which was posted to Ypres on 1 November:

Who could ever forget those two weeks of the Passchendaele show? Looking back now it all seems like one long, weird, and terrible nightmare of water-filled trenches, zigzagging duck- walks, foul slime-filled shell-holes, half-buried bodies of dead men, horses and mules, cement pillboxes, twisted wire, shrieking shells, flying humming metal, crashing aerial bombs, stinking mud, water-logged and blood-soaked stretchers – a Slough of Despond such as even a Bunyan couldn’t conceive of.

That long, wearisome “carry” from Tynecot to Frost House was like a never-ending Via Dolorosa to all who made the journey. Passchendaele was the Somme multiplied and intensified ten times over. Dark, wet, hopeless days were followed by almost endless, cold, marrow-congealing nights of despair and exhaustion. Every man was soaked through to his skin the whole time we were there, and the added weight of his sodden, muddy uniform and equipment seemed to sink him deeper into the prevailing mire. After the first few hours we moved about like so many dazed automatons, stumbling, staggering, blundering along the heaving duck-walks and erupting roads – almost too stunned to care whether we lived or died and totally indifferent to the volcanoes of smoking shell-craters about us. The hours and days and nights seemed to merge with one another into a cruelly indefinite whole and it is doubtful if any man was afterward able to distinguish one Passchendaele day’s experiences from another (Stretcher bearers at the double! p. 177).

From geometries to geographies

It’s now possible to return the evacuation map and its clockwork timings that set my discussion in motion. Maps like these display the system of evacuation as a linear geometry – an abstract grid of transmission lines that resemble what Fiona Reid in her Medicine in First World War Europe: Soldiers, Medics, Pacifists calls ‘a modernist dream’ – with no catastrophic breaks or nightmare tangles. Many official and semi-official accounts endorsed this view of ‘the cogs of the evacuating machine’, beautifully oiled and running smoothly.

But it should now be clear that this is a representation of a space that never existed beyond the paper landscape on which the military offensives were themselves planned (cf. my ‘Gabriel’s Map’, DOWNLOADS tab). Casualty evacuation was not only a geometry but also a geography; it was confounded by the bio-physical terrain through which the wounded were moved, and threatened by the savage continuity of military violence. Routes constantly had to be changed, particularly for bearer parties, and aid posts and dressing stations were endlessly re-located as medical officers struggled to adapt to changed circumstances: improvising their own posts, sketching their own maps. By extension, the analytical mapping of casualty evacuation cannot be limited to a cartography but necessarily extends to a corpography (see also ‘Corpographies’, DOWNLOADS tab) for, as Reid emphasises, the stories the wounded told of their journeys were, like so many of their injuries, ‘complicated and messy’. There was a vital reciprocity between those journeys and the bodies that made them, and I’ll elaborate on that in later posts about the woundscapes of the Western Front.

Coda

On 22 September Harvey Cushing operated on a British soldier with a serious head injury, who had been wounded the previous day. He had reached the Field Ambulance at 1230 and was admitted to the CCS at Mendinghem at 0647, whereupon he ‘got lost somehow in the crowded wards’ and was finally lifted on to Cushing’s table that afternoon. Nothing unusual about any of that, except for Cushing knowing the time when his patient had reached the Field Ambulance. He observed in passing ‘that they are noting the hour as well as the date since our discussion of last Tuesday’ (A surgeon’s journal, p. 209). His journal records that meeting, presided over by General Sloggett, but there are no details of the discussion to which Cushing refers. It’s all the more remarkable given the debate over the politics of speed – and the fact that the medical plan for Menin Road was all about minimising data recording and administration before the casualty was admitted to the CCS.

This leads me to the second Australian Army study I noticed at the start, which was carried out by the 7th Australian Field Ambulance on the Somme in July 1918 [see Appendix 16 of FA War Diary here]. It provides a useful counterpoint to the Battle of Menin Road. Here too the objective was ‘to get the men as quickly as possible to the CCS’ and this too included minimising the number of dressings and treatments en route. But where the plan for Menin Road also restricted data recording at the ADS and the MDS for the same reason, except for deaths and cases treated and returned to duty, the 7th FA added a layer by recording the time each casualty arrived at each station on the field medical card pinned to his tunic (below).

The corresponding scheme of evacuation is shown in the following sketch:

750 cases were recorded; 200 of these were retained at one of the intermediate stations (either because they were lightly wounded or because they needed emergency intervention); and of the remainder evacuation times were remarkably constant. Including treatment and travel, it took casualties 1 hour 45 minutes to be brought from the Advanced Ambulance Post (where motor ambulances collected the casualties from the regimental stretcher bearers) to the Main Dressing Station at Saint Acheul, and a further 2 hours 15 minutes (including treatment at the MDS) before they reached the CCS at Crouy: the total elapsed time of 4 hours to travel those 22 miles was reduced for some ‘special cases’ to around 3 hours.

These travel times were maintained outside any ‘push’ (a major offensive) or a ‘stunt’ (a raid). The FA provided statistics for two stunts that punctuated the steady process of attrition and these – unlike the schemas I’ve been describing thus far – incorporated the time it took stretcher bearers to retrieve casualties from the field and bring them to an aid post. The first stunt kicked off at 0310 on 4 July; the time from the Advanced Ambulance Post to the CCS was more or less unchanged (around 3 hours 30 minutes) but factoring in the time from the field to the Advanced Ambulance Post the first casualties took 5 hours 45 minutes to reach the CCS from the point of injury, and as the troops advanced further forward this increased until it took 9-10 hours for stretcher cases to reach the CCS. The second stunt started at 2030 on 7 July, and the darkness combined with rain to change the calculus: it now took 4 hours 30 minutes to 5 hours to transfer casualties from the Advanced Ambulance Post, and the first casualties took around 7 hours to reach the CCS from the point of injury; others must have taken much longer though no details were given.