Two more forthcoming books on war.

Coming in May from Cambridge University Press, a book Richard Falk hails as ‘the most significant book on international law published in the last decade’, International law and New Wars by Christine Chinkin and Mary Kaldor:

Coming in May from Cambridge University Press, a book Richard Falk hails as ‘the most significant book on international law published in the last decade’, International law and New Wars by Christine Chinkin and Mary Kaldor:

International Law and New Wars examines how international law fails to address the contemporary experience of what are known as ‘new wars’ – instances of armed conflict and violence in places such as Syria, Ukraine, Libya, Mali, the Democratic Republic of Congo and South Sudan. International law, largely constructed in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, rests to a great extent on the outmoded concept of war drawn from European experience – inter-state clashes involving battles between regular and identifiable armed forces. The book shows how different approaches are associated with different interpretations of international law, and, in some cases, this has dangerously weakened the legal restraints on war established after 1945. It puts forward a practical case for what it defines as second generation human security and the implications this carries for international law.

At 595 pages it’s clearly a blockbuster. Here is the detailed Contents list:

Part I. Conceptual Framework:

1. Introduction

2. Sovereignty and the authority to use force

3. The relevance of international law

Part II. Jus ad Bellum:

4. Self-defence as a justification for war: the geopolitical and war on terror models

5. The humanitarian model for recourse to use force

Part III. Jus in Bello:

6. How force is used

7. Weapons

Part IV. Jus Post-Bellum:

8. ‘Post-conflict’ and governance

9. The liberal peace: peacemaking, peacekeeping and peacebuilding

10. Justice and accountability

Part V. The Way Forward:

11. Second generation human security

12. What does human security require of international law?

Coming in June from Rutgers University Press, In/Visible War: the culture of war in twenty-first century America, edited by John Louis Lucaites and Jon Simons:

Coming in June from Rutgers University Press, In/Visible War: the culture of war in twenty-first century America, edited by John Louis Lucaites and Jon Simons:

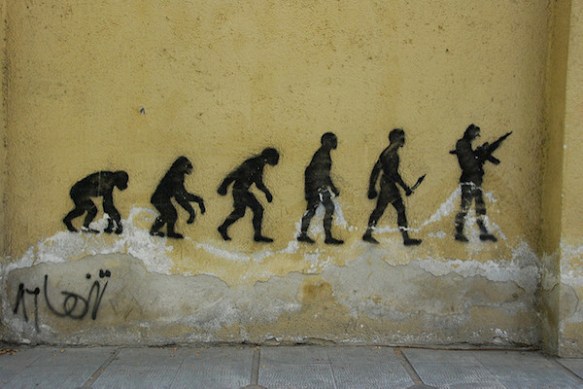

In/Visible War addresses a paradox of twenty-first century American warfare. The contemporary visual American experience of war is ubiquitous, and yet war is simultaneously invisible or absent; we lack a lived sense that “America” is at war. This paradox of in/visibility concerns the gap between the experiences of war zones and the visual, mediated experience of war in public, popular culture, which absents and renders invisible the former. Large portions of the domestic public experience war only at a distance. For these citizens, war seems abstract, or may even seem to have disappeared altogether due to a relative absence of visual images of casualties. Perhaps even more significantly, wars can be fought without sacrifice by the vast majority of Americans.Yet, the normalization of twenty-first century war also renders it highly visible. War is made visible through popular, commercial, mediated culture. The spectacle of war occupies the contemporary public sphere in the forms of celebrations at athletic events and in films, video games, and other media, coming together as MIME, the Military-Industrial-Media-Entertainment Network.

Here’s the main Contents List:

Part I: Seeing War

Chapter 1: How Photojournalism Has Framed the War in Afghanistan – David Campbell Chapter 2: Returning Soldiers and the In/visibility of Combat Trauma – Christopher J. Gilbert and John Louis Lucaites Chapter 3: (Re)fashioning PTSD’s Warrior Project – Jeremy G. Gordon Chapter 4: Unremarkable Suffering: Banality, Spectatorship, and War’s In/visibilities – Rebecca A. Adelman and Wendy Kozol “War Is Fun,” a Photo-Essay – Nina Berman Chapter 5: Laying bin Laden to Rest: A Case Study of Terrorism and the Politics of Visibility – Jody Madeira

Part II: Not Seeing War

Chapter 6: Digital War and the Public Mind: Call of Duty Reloaded, Decoded – Roger Stahl Chapter 7: A Cinema of Consolation: Post-9/11 Super Invasion Fantasy – De Witt Douglas Kilgore Chapter 8: Differential Configurations: In/visibility through the Lens of Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker (2008) – Claudia Breger Chapter 9: Canine Rescue, Civilian Casualties, and the Long Gulf War – Purnima BosePart III:

Theorizing the In/visibility of War

Chapter 10: The In/visibility of Liberal Peace: Perpetual Peace and Enduring Freedom – Jon Simons Chapter 11: Why War? Baudrillard, Derrida, and the Absolute Televisual Image – Diane Rubenstein Chapter 12: War in the Twenty-first Century: Visible, Invisible, or Superpositional? – James Der Derian