I expect many readers will know Patrick Crogan‘s Gameplay mode: war, simulation and technoculture (Minnesota, 2011). He has now uploaded what I think is a draft of Drones and global technicity: automation and (dis)individuation at academia. Here’s the extended abstract:

I expect many readers will know Patrick Crogan‘s Gameplay mode: war, simulation and technoculture (Minnesota, 2011). He has now uploaded what I think is a draft of Drones and global technicity: automation and (dis)individuation at academia. Here’s the extended abstract:

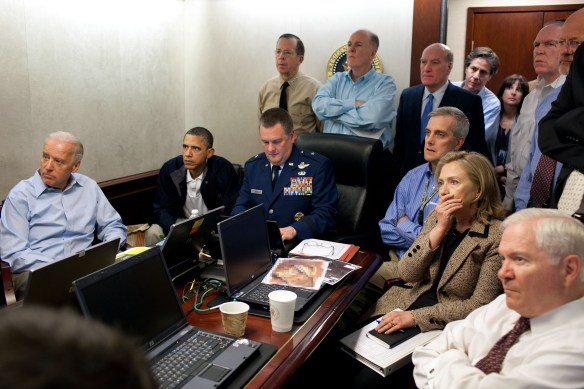

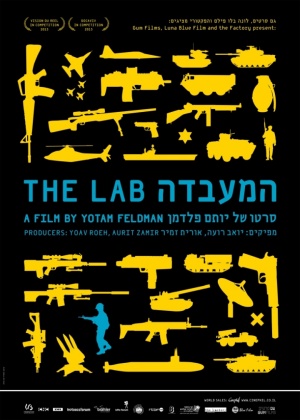

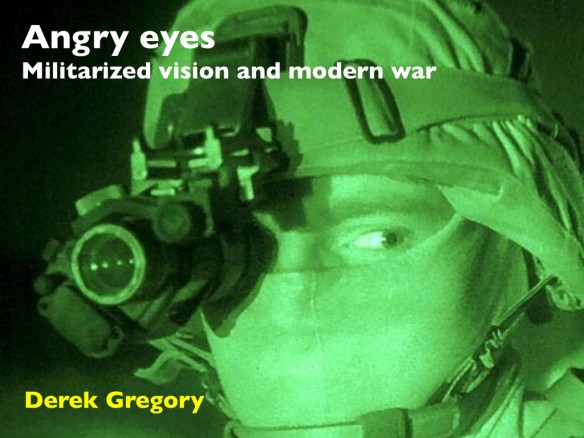

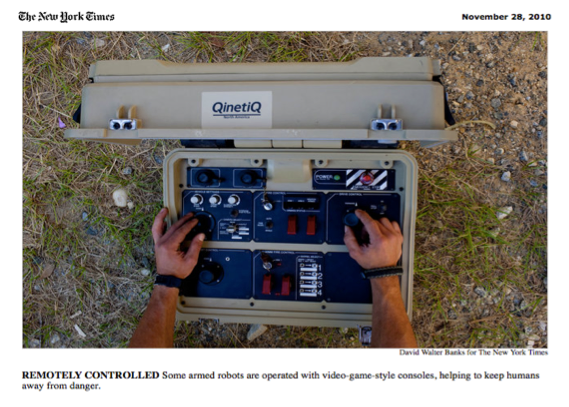

This paper (for General Organology conference [held last month at the University of Kent]) will explore the expansion of military drone usage by Western powers in the “war on terror” over the last decade or so in relation to Bernard Stiegler’s organological approach to questions concerning human historical, cultural and technological becoming.. Theorists approaching drones from different fields such as Grégoire Chamayou, Derek Gregory and Eyal Weizman have argued that the systematic and growing deployment of unmanned aerial vehicles should be understood as the “avant-garde” of a general movement toward remote and increasingly autonomous robotic systems by all branches of the armed forces of the U.S. and many of allies and competitors. These developments put into question all established cultural political, legal and ethical framings of war, peace, territory, civilian and soldier in the societies of the “advanced powers” on behalf of which these systems are deployed. Animating this indetermination is what Chamayou calls the “tendency inherent in the material development of drones” leading to this profound undoing of cultural and geopolitical moorings. I will explore the organological nature of this tendency inherent in drone materiality and technology, concentrating on the virtualizing, realtime digital developments in remotely controlled and increasingly automated robotic systems.

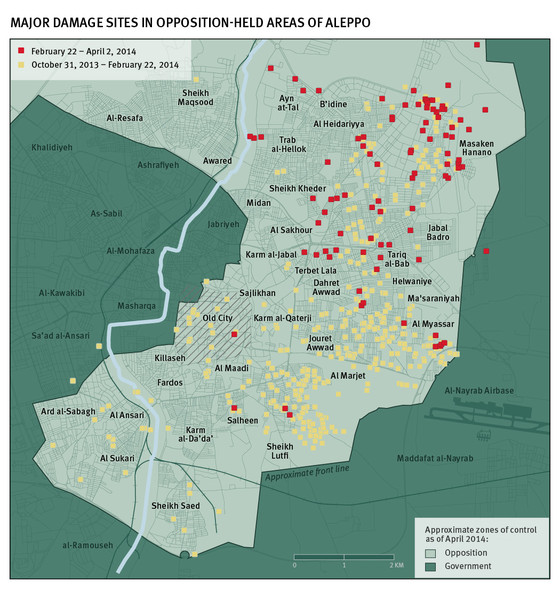

The projection of a simulational model of the contested space over the inhabited world is a constitutive part of this tendency. Indeed, the inhabitants of the spaces of concern in the war on terror—which in principle and increasingly in practice are everywhere—are better understood as environmental elements or “threats” in what simulation engineer and theorist Robert Sargent has called the “problem space” the computer simulation designer seeks to model conceptually in order to make the simulation serve as an effective solution. A specifically designed spatio-temporality is enacting a performative, “operational” and automated reinvention of the lived experience of both inhabiting and contesting the control of space in time.

If, as the above writers have shown, this projection of and over “enemy territory” has clear precedents in European colonialist strategies and procedures, what is unprecedented today is the digitally-enabled expansion and intensification of this spatio-temporal reanimation of the world. This reanimation must be understood as key contributor to a transformative and extremely problematic pathway toward the automation of military force projection across the globe. This essay will analyse the nature and implications of these transformative digital modellings of the enemy in and as milieu, a milieu as tiny as the space around a single ‘target’ and as large as the world, existing both in a brief “window of opportunity” and within a permanent realtime of preemptive pan-spectrum surveillance.

From an organological perspective developments in drone technics must also be approached as a particularly pressing political and ethical challenge of the global transformations of human technicity in the digital “epoch”—or rather, in the generalised crisis of epochality and spatio-temporal orientation that Stiegler sets out to thematise and respond to in his “philosophical activism”. If as Stiegler provocatively suggests in Technics and Time 1: The Fault of Epimetheus) human being had a “second origin” in the historical development of the West which achieved its culmination its “worldwide extension”, it is one whose epoch has led us tendentially and increasingly rapidly to the crisis of ethnocultural idiomatic differentiation and specificity (as he argues in Technics and Time 2: Disorientation). The history of Western techno-capitalist, imperial colonisations, wars and subsequent post-colonial globalisation is attaining its full extent and its exacerbation, readable in the above noted indeterminations of war, peace, sovereignty, citizenship and so on. What goes with this is a doubled movement (which Virilio termed “endocolonisation”) of intensification of the reorganisation of social and individual surveillance, control and regulation via realtime, pervasive digital technical regimes. The systematic deployment of computational abstraction, simulational virtualisation and anticipatory, realtime preemptive materialisation of this doubled movement is perceivable in all its cultural-political, conceptual and technological complexity in drone technics. Indeed, drones are a major driver of research and development in automation and AI for the spectrum of what the U.S.A.F calls the “perceive and act vector”, as well as for “big data” processing in realtime to handle ever-growing monitoring and surveillance feeds.

Today a voluntarist and cynical (and nihilist in Stiegler’s view) adoption of the automatising potentials of digital technics supports the rapid advances in drone systems (and I have proposed that an “elective naivety” sustains this in the academy, across scientific and humanities disciplinary contexts). From Stiegler’s organological perspective, I will argue that the autonomy of human agency is always composed with various automated functions that form part of our material, prosthetic conditions of existence. By addressing some of the inherent contradictions arising from the proposed development of fully autonomous military robotic systems, I hope to contribute toward the urgently needed “redoubling” of the first adoption of the possibilities of digital automation evidenced in drone technics (as the “logical” outcome in strategic-political terms of the latest advances of computer technology). To “re-double” technocultural becoming reflectively, critically, in the name of a less inhuman potential of automated digital technics is the responsibility of those able to read and write, to reflect and respond to the accelerating epochal transformation of the world in this “our” era of the permanent war on terror. This is the horizon in which “we” maintain the possibility of a non-inhuman future (or further “re-birth”) for contemporary humanity. For, as Stiegler has argued in What Makes Life Worth Living, this is a better way to think the present and future than that implied in the term “post-human”, for the human remains a project and a projection and not a superceded entity.

Bernard Stiegler (above) was a keynote speaker at the conference, and if you want some tantalising glimpses into some of the other possibilities opened out by his ideas for the analysis of drones, I’d recommend James Ash, ‘Technology and affect: Towards a theory of inorganically organised objects’, Emotion, space and society (in press, 2014) – incidentally, James reviews Gameplay mode in Cultural politics 8 (3) (2012) 495-497 – and Sam Kinsley‘s ‘The matter of virtual geographies’, Progress in human geography (2014) 38 (3) (2014) 364-84.

As you can see from the abstract, Patrick also engages with my work and, crucially, Gregoire Chamayou‘s, and since the English-language translation of Theory of the drone is published at the end of this month I thought it might be helpful to list and link to my detailed commentaries on the book in one place, so here they are:

Theory of the drone 1: Genealogies

Theory of the drone 2: Hunting

Theory of the drone 3: Killing grounds

Theory of the drone 4: Pennies from heaven [on counterinsurgency/COIN]

Theory of the drone 5: Vulnerabilities

Theory of the drone 6: Sacrifice, suicide and drones

Theory of the drone 7: Historical precedents and postcolonial amnesia

Theory of the drone 8: From invisibility to vulnerability

Theory of the drone 9: Psychopathologies of the drone

Theory of the drone 10: Killing at a distance

You can also find my essay on ‘Drone geographies’ from Radical Philosophy (2014) under the DOWNLOADS tab.

Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer‘s combative review of Theory of the drone, ‘Ideology of the drone’, is here and my extended commentary on that review is here. Simon Labrecque provides another review here, invoking the USAF’s own description of its remote missions: ‘Projeter du pouvoir sans projeter de vulnérabilité.’

Meanwhile over at the Funambulist Papers, Stuart Elden suggested one way of wiring Grégoire’s previous book Manhunts to Theory of the drone here, while Grégoire’s own postscript (which suggests another route) is here.

Expect more commentary once the English edition is out.