This is the 12th in a series of extended posts on Grégoire Chamayou‘s Théorie du drone and covers the final chapter in Part III: Necro-ethics, called ‘Précisions’; in French the singular means accuracy, as you might expect, but the plural means ‘details’ – which is, of course, where the devil is to be found…

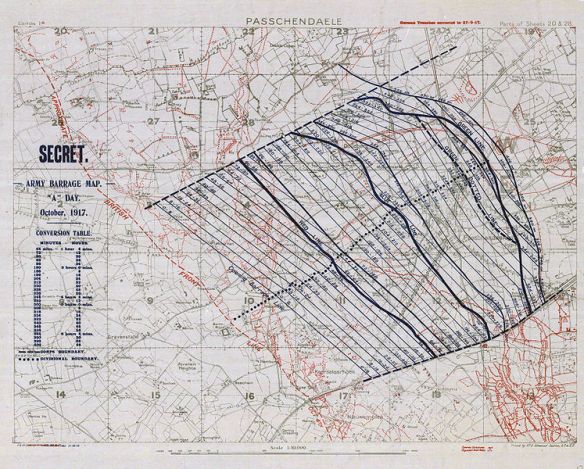

One of the most common claims advanced by those who defend the use of armed drones is that they reduce ‘collateral damage’ because they are so precise. Following directly from his previous critique of Bradley Jay Strawser, Chamayou cites him again here: ‘Drones, for all their current and potential misuse, have the potential for tremendous moral improvement over the aerial bombardments of earlier eras.’ But he dismisses this as a misleading comparison: if Dresden or Hiroshima are taken as the yardstick against which accuracy is to be measured – or, for that matter, as the standard against which military ethics are to be judged – then virtually any subsequent military operation would pass both tests with flying colours.

The comparison confuses form with function. Compared to Lancaster bombers and Flying Fortresses (even with their famous Norden bombsights: for Malcolm Gladwell on the ‘moral importance’ of the bombsight to Norden, a committed Christian, see here and here; for more on the bombsight, see here), the Predator and the Reaper are evidently more accurate. But Chamayou insists that the real comparison ought to be with other tactical means currently available to achieve the same objective.

In the kill/capture raid against Osama Bin Laden on 1 May 2011 (assuming ‘capture’ was ever on the agenda), he argues that the choice was between drones and Special Forces not between drones and re-staging Dresden in Abbotabad. This doesn’t quite work, since the raid was carried out by US Navy Seals who swept in from Bagram via Jalalabad by helicopter, but the mission also depended on real-time imagery from an RQ-170 stealth drone (‘the Beast of Kandahar’). This was the source of the live video feed watched by Obama and members of his administration in the famous ‘Situation Room’ photograph [on which, see Keith Feldman on ‘Empire’s Verticality’ in Comparative American Studies 9 (4) (2011) 325-41].

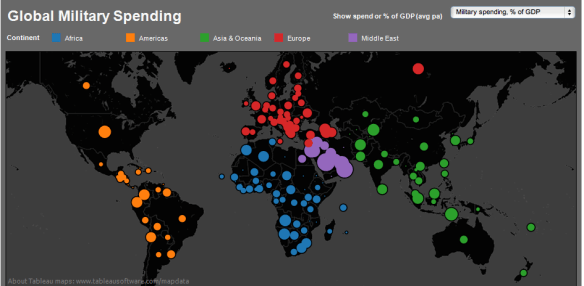

The RQ-170 is an unarmed platform, but its role should remind us that drones are part of networked warfare – even when strikes are carried out by other means, the enhanced intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance capabilities provided by the long dwell-times of these remote platforms mean that they are instrumental in the activation of the kill-chain. This holds for military operations far beyond targeted killing: in Afghanistan between 2009 and 2011 drones were directly responsible for only 5-6 per cent of weapons released by the US Air Force, but they no doubt played a vital role in the release of many of the others.

Still, Chamayou’s basic point is a sharp one – and I rehearsed similar arguments in my discussion of The politics of drone wars last year – but readers of Jeremy Scahill‘s Dirty Wars may still reasonably object that the civilian casualties resulting from JSOC’s infamous night raids in Afghanistan cast doubt on the precision and accuracy of ground forces too. Gareth Porter has estimated that more than 1,500 civilians were killed in night raids in just ten months in 2010-11, making them ‘by far the largest cause of civilian casualties in the war in Afghanistan.’ Indeed, Afghan protests have frequently centred on the civilian toll exacted by drones and night raids.

Still, Chamayou’s basic point is a sharp one – and I rehearsed similar arguments in my discussion of The politics of drone wars last year – but readers of Jeremy Scahill‘s Dirty Wars may still reasonably object that the civilian casualties resulting from JSOC’s infamous night raids in Afghanistan cast doubt on the precision and accuracy of ground forces too. Gareth Porter has estimated that more than 1,500 civilians were killed in night raids in just ten months in 2010-11, making them ‘by far the largest cause of civilian casualties in the war in Afghanistan.’ Indeed, Afghan protests have frequently centred on the civilian toll exacted by drones and night raids.

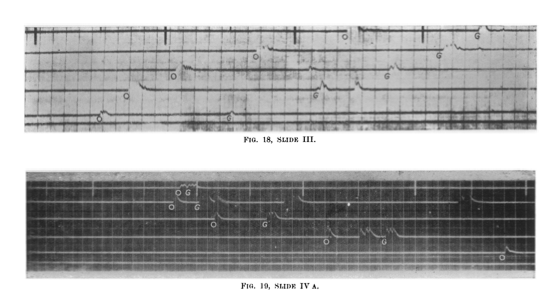

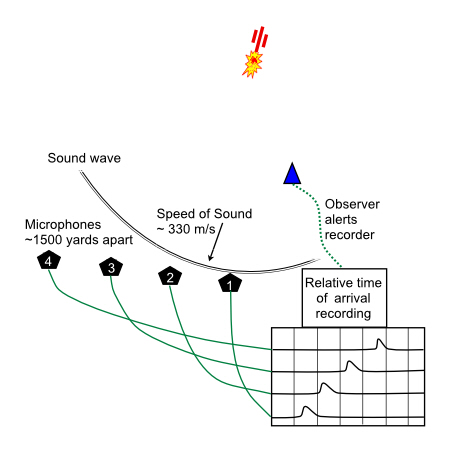

Even if the appropriate comparison is between different modalities of military violence in the present, Chamayou argues that the discussion is bedevilled by another series of confusions about ‘accuracy’ or ‘precision’. In fact, though he doesn’t say so, the the two terms aren’t interchangeable. Strictly speaking, accuracy refers to the deviation from the aiming point, precision to the dispersion of the strike:

CEP in the diagram above refers to the Circular Error Probable, once described by the Pentagon as ‘an indicator of the delivery accuracy of a weapon system’, which is a circle of radius n described around the aiming point. Assuming a bivariate normal distribution, then – all other things being equal (which they rarely are) – 50% of the time a bomb, missile or round will land within the circle: which of course means that the other half of the time it won’t, even under ideal experimental conditions. As this is a normal distribution, then 93 per cent should land within 2n and more than 99 per cent within 3n.

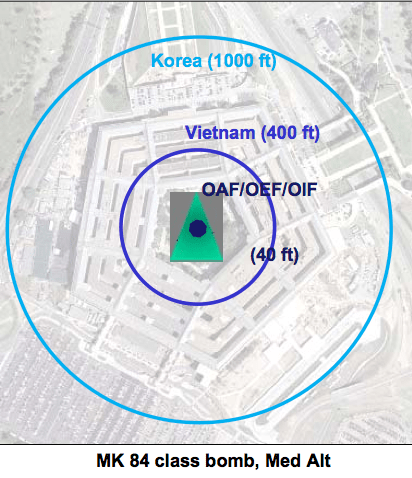

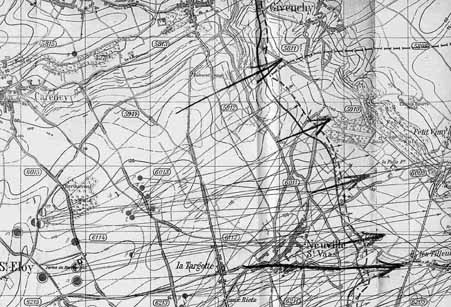

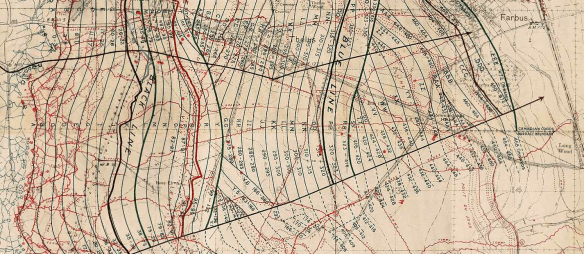

Chamayou doesn’t refer to the CEP directly, only briefly to the ‘accuracy of fire’, but – to revert to the comparison he refuses – the CEP of bombing from the air has contracted dramatically since the Second World War when it was around 3,000 feet (though this improved over time): so much so that David Deptula, when he was USAF Deputy Chief of Staff for ISR, used to talk of crossing a ‘cultural divide of precision and information’. The image below, taken from one of his presentations, shows the contraction (notice that the aim point is the Pentagon….).

Interestingly, the most recent Joint Publication (3-60) from the Joint Chiefs of Staff on Targeting (January 2013) has explicitly removed the concept from its Terms and Definitions, citing as its authority the Department of Defense’s Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (it was still there on 31 January 2011, but no longer). I haven’t been able to discover the reasons for the change, though there is longstanding scepticism about the validity of the measure: see, for a specific example, Donald MacKenzie‘s classic discussion in Inventing accuracy: a historical sociology of nuclear missile guidance (1993, pp. 352-7). I’ve seen several comments to the effect that the measure isn’t useful for ‘smart bombs’ because they don’t display the same spread as ‘dumb bombs’. (There’s a quick primer on the emergence of smart bombs during the Vietnam War here, and an account of the evolution of ‘precision strike’ since then here; for more detail, try David Koplow‘s Death by moderation: the US military’s quest for useable weapons (2009)).

The MQ-1 Predator carries two AGM-114 Hellfire missiles [shown below, top; for acronyphiles, AGM designates an Air-to-Ground Missile, while the ‘Hellfire’ was originally developed as a ‘Helicopter-Launched Fire-and-Forget Missile’; its main platform is still an attack helicopter], while the MQ-9 Reaper can carry four AGM-114 Hellfire Missiles or replace two of them with GBU-12 Paveway II bombs [GBU = Guided Bomb Unit; shown below, bottom].

Both weapons systems are laser-guided; the sensor operator, sitting beside the pilot in the Ground Control Station, uses a laser targeting marker (LTM) to ‘paint’ the target – this can also be done by ground troops in conventional combat zones – but its accuracy can be compromised by cloud, smoke, fog or dust. (This is why the Air Force also uses GPS-guided weapons; they are less accurate but unaffected by these environmental conditions). Once the necessary clearances have been obtained from mission commanders and military lawyers, the pilot fires the missile and the sensor operator guides it on to its target.

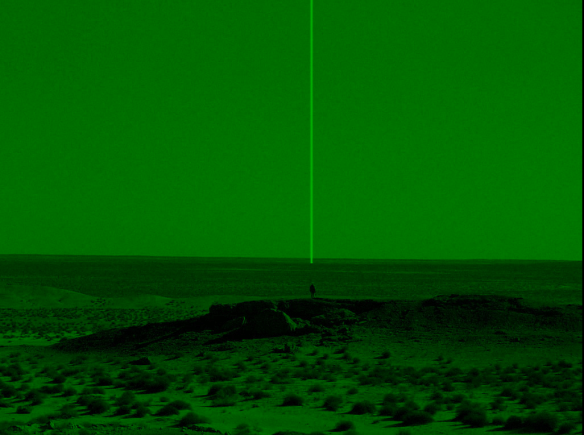

Omer Fast‘s interview with a sensor operator (‘Brandon’ – whether this is a pseudonym or really Brandon Bryant is hard to know) for 5,000 Feet is the Best provides a series of insights into the operation in Afghanistan and Iraq. You can’t see the beam with the naked eye, but American ground troops can see it with their infrared goggles. According to ‘Brandon’, they call it the ‘Light of God’ (really); the image below is James Bridle‘s replication of the effect based on laser targeting night systems and a CC-licensed photograph of the Iraqi desert by Rob Bakker.

‘Brandon’:

‘Usually the laser track is about half the size of this [hotel] room. Poof! By the time it hits the ground… a lot of times it turns into a square for some reason… It could be anywhere from ten feet by ten feet to twenty feet by twenty feet… It starts off small and you watch it kind of open up’

This is not exactly putting ‘warheads on foreheads‘, but ‘Brandon’ explains that the crew is also required to identify a secondary ‘abort’ target.

‘… some of the contingencies we have to worry about are: if we’re firing at a building and somebody crosses – maybe – who knows, a group of children starts crossing in front of the building, we need a second site once that missile is already off the rails. To go ahead and drop that missile so that we don’t harm the children So usually we’ll choose an alternate site a couple hundred feet to a couple of hundred yards away. It might be an empty field. And we use that as the backup…

So let’s say we get the missile off the rail and a group of kids comes into play: I call “abort” and I’ll start moving that laser over to an empty site so that we can detonate there and not cause any additional loss of life.’

Sounds good, but the real Brandon Bryant (above) has a different story to tell; it turns out that there is an eight-second window in which the missile can be diverted:

With seven seconds left to go, there was no one to be seen on the ground. Bryant could still have diverted the missile at that point. Then it was down to three seconds. Bryant felt as if he had to count each individual pixel on the monitor. Suddenly a child walked around the corner, he says.

Second zero was the moment in which Bryant’s digital world collided with the real one in a village between Baghlan and Mazar-e-Sharif.

Bryant saw a flash on the screen: the explosion. Parts of the building collapsed. The child had disappeared. Bryant had a sick feeling in his stomach.

“Did we just kill a kid?” he asked the man sitting next to him.

“Yeah, I guess that was a kid,” the pilot replied.

“Was that a kid?” they wrote into a chat window on the monitor.

Then, someone they didn’t know answered, someone sitting in a military command center somewhere in the world who had observed their attack. “No. That was a dog,” the person wrote.

They reviewed the scene on video. A dog on two legs?

Even then, think about that blossoming square, twenty feet by twenty feet. Then factor in the Circular Error Probable of a Hellfire missile, which is usually calculated at between 9 and 24 feet. The ‘pinpoint’ accuracy of the missile is starting to blur and the ‘surgical’ strike beginning to blunt. In fact, the development of the Hellfire missile suggests another narrative. In 1991 the Pentagon was already advertising the Hellfire as capable of ‘pinpoint’ accuracy, and since then it has been upgraded more than half a dozen times, each version promising greater accuracy: as Matthew Nasuti asks in his catalogue of Hellfire errors, what can be more accurate than ‘pinpoint accurate’?

In any case, narrowing the discussion to the CEP misses two things. First, as former USAAF officer Peter Goodrich points out in his discussion of ‘The surgical precision myth‘, this ‘totally disregards what happens after the bomb explodes’. What Goodrich has in mind is the blast and fragmentation radius, which Chamayou calls ‘the kill radius’. Fast’s ‘Brandon’ insists

‘All of us are taught about how far those Hellfire missiles go, how far their frag goes. And “danger close” as we call it when you have troops that are very close or civilians that are present. They’re just factors that you have to work in to bring down the percentages of the harm that could be done.’

In the targeting cycle the US Air Force enters those ‘factors’ into both collateral damage estimation and ‘weaponeering’, modifying the missile or bomb to restrict its blast and fragmentation radius. Chamayou reports that the Hellfire missile has a ‘kill radius’ of 50 feet (15 metres) and a ‘wounding radius’ of 65 feet (20 metres); the GBU-12 Paveway II has a ‘casualty radius’ of between 200 and 300 feet (within which 50 per cent of people will be killed). These calculations aren’t exactly equivalent – and it’s difficult to obtain precise and comparable figures – but nothing about this is as precise as the rhetoric implies. As Chamayou asks:

‘In what fictional world can killing an individual with an anti-tank missile [the Hellfire] that kills every living thing within a radius of 15 metres and wounds everyone else within a radius of 20 metres be seen as “more precise”?’

All those who are killed or wounded within the casualty radius are presumably guilty by proximity.

This is Chamayou’s second rider, which relates to what happens before the bomb or missile is released: to the production – the US military sometimes calls it the ‘prosecution’ – of the target. In this sense, the technical considerations I’ve just described are beside the point (sic). All of the calibrations I’ve set out in such detail apply to missiles and bombs irrespective of the platform used to deliver them; what is supposed to distinguish a Predator or a Reaper from a conventional strike aircraft or attack helicopter is that it combines ‘hunter’ and ‘killer’ in a single platform and, specifically, that its real-time full-motion video feeds enable crews (and others in the loop) to see what they are doing in unprecedented detail.

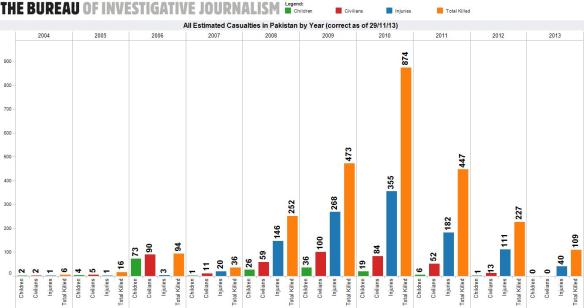

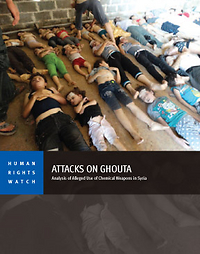

Does this political technology of vision make it possible, as advocates claim, to distinguish between combatants and civilians more effectively than ever before? Here Chamayou rehearses common criticisms: that in standard US military practice ‘combatant’ morphs into ‘militant’, even ‘presumed militant’ and, at the hideous limit, into ‘military-aged male’ – counting ‘all military-age males in a strike zone as combatants … unless there is explicit intelligence posthumously proving them innocent’ – and that this process of (so to speak, performative) militantisation as Chamayou calls it is underwritten by a techno-judicial probabilisation (again his term) whose ‘epistemology of suspicion’ allows signature strikes that target un-named and unknown people on the basis of their ‘pattern of life‘.

Does this political technology of vision make it possible, as advocates claim, to distinguish between combatants and civilians more effectively than ever before? Here Chamayou rehearses common criticisms: that in standard US military practice ‘combatant’ morphs into ‘militant’, even ‘presumed militant’ and, at the hideous limit, into ‘military-aged male’ – counting ‘all military-age males in a strike zone as combatants … unless there is explicit intelligence posthumously proving them innocent’ – and that this process of (so to speak, performative) militantisation as Chamayou calls it is underwritten by a techno-judicial probabilisation (again his term) whose ‘epistemology of suspicion’ allows signature strikes that target un-named and unknown people on the basis of their ‘pattern of life‘.

But both these procedures and, indeed, the criticisms of them, obscure what is for Chamayou, the fundamental paradox, what he calls the ‘profound contradiction’. International law defines a combatant and thus a legitimate target in terms of direct participation in hostilities and an imminent threat. It’s more complicated than that, as I’ll show later, but this is enough for Chamayou to fire off two key questions: How can anyone be participating in hostilities if there is no longer any combat? How can there be any imminent threat if there are no troops on the ground? The drone, praised for its forensic ability to distinguish between combatant and non-combatant, in fact abolishes the condition necessary for such a distinction: combat itself (p. 203; also p. 208).

It’s an artful claim, but it oversimplifies the situation. Chamayou has (once again) confined the discussion to targeted killing but, as I’ve repeatedly emphasised, Predators and Reapers have also been used for other purposes in Iraq and Afghanistan, including the provision of ‘armed overwatch’ and close air support to ground troops. Outside these war-zones – in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia and elsewhere – the critique is a powerful one (which is not to say that Obama’s lawyers have not claimed a legal warrant for their supposedly covert drone strikes in these areas: more on this later too). Still, Chamayou’s argument loops back to earlier discussions about the intrinsic non-reciprocity of drone warfare.

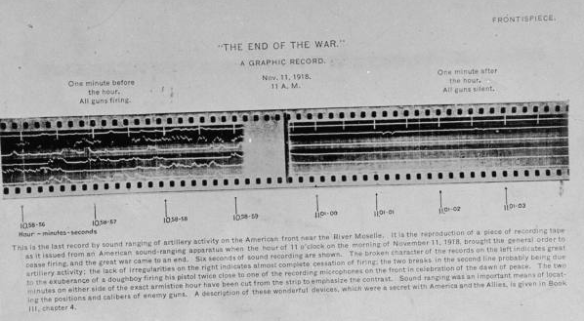

And here Chamayou closes with a powerful argument. If ethics is classically about how to live well and die well, he suggests that necro-ethics is a doctrine of ‘killing well’. He notes that critics of the covert drone wars demand, time and time again, transparency. They want to know the legal armature and adjudicative apparatus for the strikes, the rules and procedures that are followed, and the lists of casualties. But he argues that their demands turn the issue into an arid juridico-administrative formalism endorsed by bureaucratic Reason. In the kill zones, he says ruefully, there are no legal memoranda, no columns of numbers or ballistics reports (p. 207): these are the very formularies of necro-ethics. And, as I’ve noted, there are no air-raid warnings, no anti-aircraft defences and no air-raid shelters either.

It’s in that spirit that Chamayou closes the chapter with an extended quotation from Madiha Tahir’s ‘Louder than bombs‘:

I dream that my legs have been cut off, that my eye is missing, that I can’t do anything … Sometimes, I dream that the drone is going to attack, and I’m scared. I’m really scared.

After the interview is over, Sadaullah Wazir pulls the pant legs over the stubs of his knees till they conceal the bone-colored prostheses.

The articles published in the days following the attack on September 7, 2009, do not mention, this poker-faced, slim teenage boy who was, at the time of those stories, lying in a sparse hospital in North Waziristan, his legs smashed to a pulp by falling debris, an eye torn out by shrapnel. nor is there a single word about the three other members of his family killed: his wheelchair-bound uncle, Mautullah Jan and his cousins Sabr-ud-Din Jan and Kadaanullah Jan. All of them were scripted out of their own story till they tumbled off the edge of the page.

Did you hear it coming?

No.

What happened?

I fainted. I was knocked out.

As Sadaullah, unconscious, was shifted to a more serviceable hospital in Peshawar where his shattered legs would be amputated, the media announced that, in all likelihood, a senior al-Qaeda commander, Ilyas Kashmiri, had been killed in the attack. The claim would turn out to be spurious, the first of three times when Kashmiri would be reported killed.

Sadaullah and his relatives, meanwhile, were buried under a debris of words: “militant,” “lawless,” “counterterrorism,” “compound,” (a frigid term for a home). Move along, the American media told its audience, nothing to see here.

Some 15 days later, after the world had forgotten, Sadaullah awoke to a nightmare.

Do you recall the first time you realized your legs were not there?

I was in bed, and I was wrapped in bandages. I tried to move them, but I couldn’t, so I asked, “Did you cut off my legs?” They said no, but I kind of knew.

When you ask Sadaullah or Karim or S. Hussein and others like them what they want, they do not say “transparency and accountability.” They say they want the killing to stop. They want to stop dying. They want to stop going to funerals — and being bombed even as they mourn. Transparency and accountability, for them, are abstract problems that have little to do with the concrete fact of regular, systematic death.’

And Madiha adds this: ‘The technologies to kill them move faster than the bureaucracies that would keep more of them alive: a Hellfire missile moves at a thousand miles per hour; transparency and accountability do not.’

Indeed they don’t; Sadaullah died last year, Mirza Shahzad Akbar reports, ‘without receiving justice or even an apology.’ Not even killing well, then.