The US military defines Close Air Support (CAS) as ‘air action by fixed-wing and rotary-wing aircraft against hostile targets that are in close proximity to friendly forces, and [it] requires detailed integration of each air mission with the fire and movement of those forces.’ It’s a difficult and dangerous business, and not only for the intended targets.

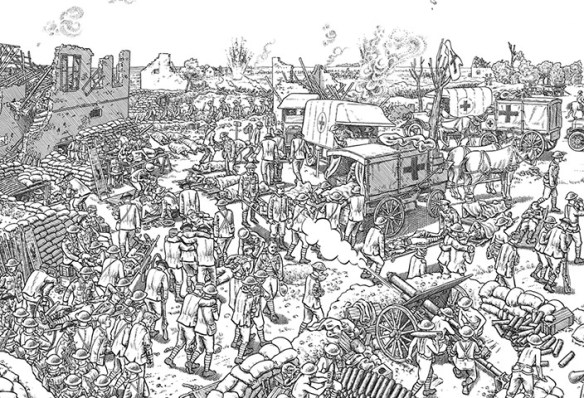

The technologies of CAS have been transformed but, according to the the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, its fundamentals haven’t changed since the First World War.

‘Pilots and dismounted ground agents must ensure they hit only the intended target using just voice directions and, if they’re lucky, a common paper map. It can often take up to an hour to confer, get in position and strike—time in which targets can attack first or move out of reach.’

To achieve what is in effect the time-space compression of the kill-chain, DARPA is developing its Persistent Close Air Support program to provide an all-digital system. The system ‘lets a Joint Tactical Air Controller call up CAS from a variety of sources, such as aircraft or missile platforms, to engage multiple, moving and simultaneous targets,’ explains David Szondy (from whom I’ve borrowed the short-hand ‘digital airstrikes’). ‘By eliminating all the radio chatter and map fumbling, the exercise is much faster and more accurate with reduced risk of friendly fire incidents.’ The program manifesto, for want of a better word, includes these aims and specifications:

The program seeks to leverage advances in computing and communications technologies to fundamentally increase CAS effectiveness, as well as improve the speed and survivability of ground forces engaged with enemy forces.

The program envisions numerous benefits, including:

- Reducing the time from calling in a strike to the weapon hitting the target by a factor of 10, from up to 60 minutes down to just 6 minutes

- Direct coordination of airstrikes by a ground agent from manned or unmanned air vehicles

- Improved speed and survivability of ground forces engaged with enemy forces

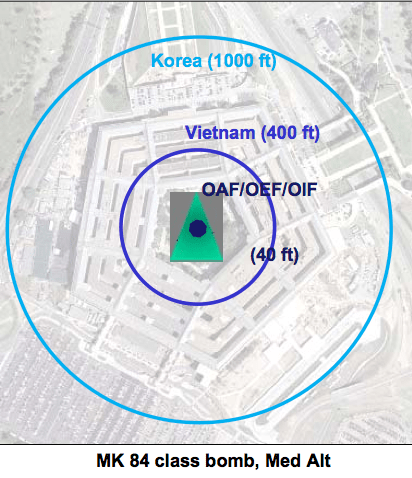

- Use of smaller, more precise munitions against smaller and moving targets in degraded visual environments

- Graceful degradation of services—if one piece of the system fails, warfighters would still retain CAS capability

PCAS has two components:

The first is PCAS-Air, which … involves the use of internal guidance systems, weapons and engagement management systems, and communications using either the Ethernet or aircraft networks for high-speed data transmission and reception. PCAS-Air processes the data received, and provides aircrews via aircraft displays or tablets with the best travel routes to the target, which weapons to use, and how best to use them.

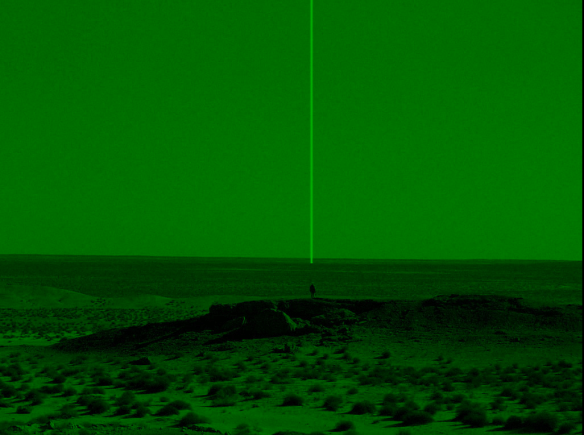

The other half is PCAS-Ground, intended for improved mobility, situational awareness and communications for fire coordination. Soldiers on the ground can use an HUD eyepiece wired to a tablet that displays tactical imagery, maps, digital terrain elevation data, and other information [the image above is an artist’s impression of the Heads-Up Display]. This means they can receive tactical data from PCAS without having to keep looking at a computer screen.

PCAS-Ground has been deployed in Afghanistan since December 2012. The original plan, as the emphasis on ‘persistent’ implies, was to integrate the system with drones, but after the cancellation of the US Air Force’s MQ-X (‘Avenger’) program Raytheon announced that PCAS would be developed using a conventional A-10 Thunderbolt.

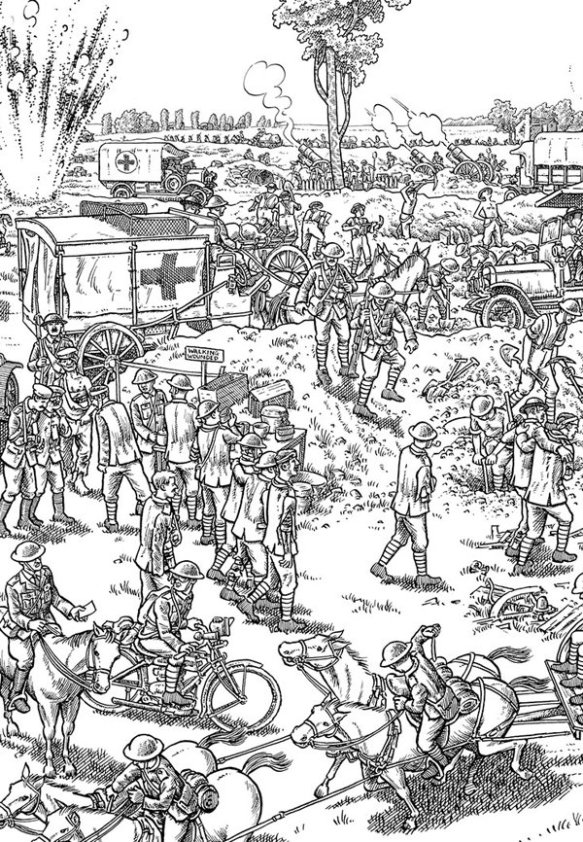

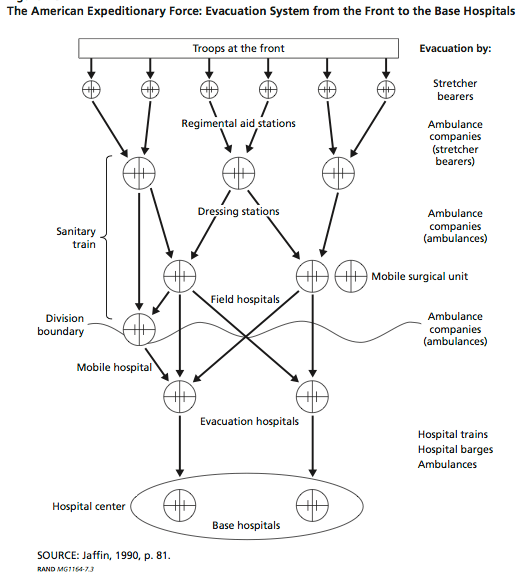

There is of course a long history to the digitisation and automation of the battlespace, and that reference to the First World War was not an anachronism. There were such intimate links between mapping, aerial photography and artillery ranging on the Western Front – whose cascade of updated imagery and intelligence underwrote the seeming stasis of trench warfare – that Peter Chasseaud described the result as ‘a sophisticated three-dimensional fire-control data base’ through which ‘in effect, the battlefield had been digitised.’ It was also, in a sense, automated; I discuss this in detail in ‘Gabriel’s Map’, but it’s captured perfectly in Tom McCarthy‘s novel C.

More obvious way stations to the present include the Vietnam-era Electronic Battlefield, whose sensor-shooter system I described in ‘Lines of descent’ (DOWNLOADS tab) as a vital precursor to today’s remote operations:

Another was the development of the PowerScene digital terrain simulation that was used to identify target imagery transmitted by proto-Predators over Bosnia-Hercegovina and to rehearse NATO bombing missions.

Remarkably, it was also used at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base during the negotiations that led to the Dayton peace accords. As one US officer explained: ‘It’s an instrument of war but we’ll use it for peace because you are willing to come to the table’. The system was used to explore proposals for potential boundaries, but the sub-text was clear: if agreement could not be reached, NATO had a detailed military knowledge of terrain and targets. (For more, see James Hasik‘s Arms and innovation: entrepreneurship and alliances in the twenty-first century defense industry (2008) Ch. 6: ‘Mountains Miles Apart’; Richard Johnson‘s ‘Virtual Diplomacy’ report here; and a precocious paper by Mark Corson and Julian Minghi here, from which I’ve taken the image on the left).

Remarkably, it was also used at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base during the negotiations that led to the Dayton peace accords. As one US officer explained: ‘It’s an instrument of war but we’ll use it for peace because you are willing to come to the table’. The system was used to explore proposals for potential boundaries, but the sub-text was clear: if agreement could not be reached, NATO had a detailed military knowledge of terrain and targets. (For more, see James Hasik‘s Arms and innovation: entrepreneurship and alliances in the twenty-first century defense industry (2008) Ch. 6: ‘Mountains Miles Apart’; Richard Johnson‘s ‘Virtual Diplomacy’ report here; and a precocious paper by Mark Corson and Julian Minghi here, from which I’ve taken the image on the left).

PowerScene was later used by USAF pilots rehearsing simulated bombing missions against Baghdad in the 1990s (see right) – the system fixed target co-ordinates and red ‘bubbles’ displayed threats calibrated on the range of surface-to-air missile systems – and when Anteon Corporation and Lockheed Martin introduced TopScene air strikes over Afghanistan in 2001 were also rehearsed over digital terrain.

PowerScene was later used by USAF pilots rehearsing simulated bombing missions against Baghdad in the 1990s (see right) – the system fixed target co-ordinates and red ‘bubbles’ displayed threats calibrated on the range of surface-to-air missile systems – and when Anteon Corporation and Lockheed Martin introduced TopScene air strikes over Afghanistan in 2001 were also rehearsed over digital terrain.

But there is another side to all this, because digital platforms can also be used to enable others to display and interrogate the geography of air strikes. I’ve discussed this before in relation to the CIA-directed program of targeted killing in Pakistan here and here, but impressive progress has also been made in plotting air strikes across the border in Afghanistan.

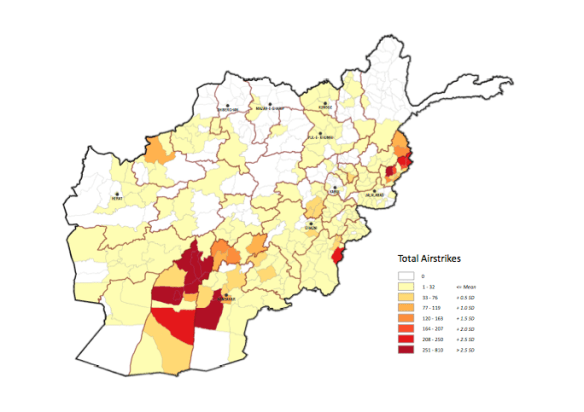

The most remarkable use of USAF/ISAF data that I know is Jason Lyall‘s work in progress on what he calls ‘Dynamic coercion in civil wars’ – ‘Are airstrikes an effective tool of coercion against insurgent organizations?’ – which focuses on air strikes in Afghanistan between 2006 and 2011. This is part of a book project, Death from above: the effects of airpower in small wars; the most recent version of the relevant analysis is here. The map below is Jason’s summary of air strikes in Afghanistan 2006-11, but as I’ll explain in a moment, it gives little idea of the critical digital power that lies behind it.

First, the original USAF/ISAF data was in digital form, but transforming it into a coherent and consistent geo-coded database has involved a truly extraordinary enterprise:

We draw on multiple sources to construct a dataset of nearly 23,000 airstrikes and shows of force in Afghanistan during 2006-11. The bulk of the dataset stems from newly-declassified data from the Air Forces Central’s (AFCENT) Combined Air Operations Center (CAOC) in Southwest Asia, which recorded the location, date, platform, and type/number of bombs dropped for January 2008 to December 2011 in Afghanistan. These data required extensive cleaning to ensure that a consistent standard for each type of air operation was maintained and duplicates dropped. These data were supplemented by declassified data from the International Security Assistance Force’s (ISAF) Combined Information Data Exchange Network (CIDNE) for the January 2006 to December 2011 time period. Finally, additional records from press releases by the Air Force’s Public Affairs Office (the “Daily Airpower Summary,” or DAPS) were also incorporated. … Each air operations’ intended target was confirmed using at least two independent coders drawing on publicly available satellite imagery. Merging of these records was extremely labor intensive, not least because of the near total absence of overlap between CAOC, CIDNE, and DAPS records. Only 448 events were found in all three datasets, underscoring the problems inherent in single-sourcing data, even official data, in conflict settings (my emphasis).

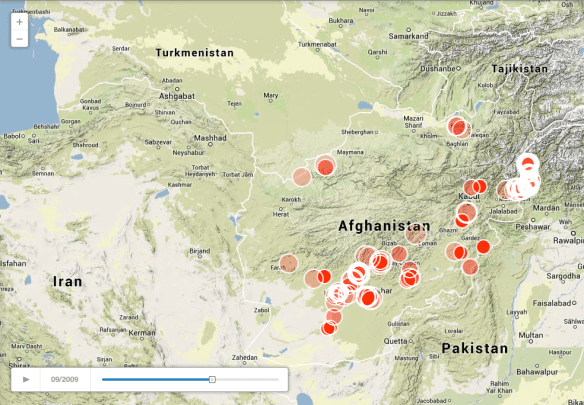

Second, to get the full visual effect of Jason’s analysis you absolutely need to see the animation that he’s made available on his website here; the image below is just a screenshot for September 2009 (I’ll explain why I chose that month in my next post).

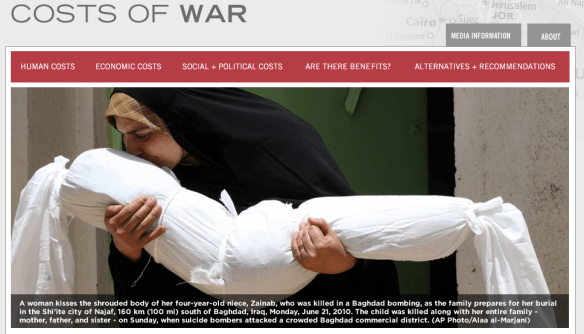

But what about casualty figures? Josh includes a summary map of 216 air strikes involving acknowledged civilian casualties, taken from the same military databases (with all their limitations), and in January 2011 the US military released its data on ‘CIVCAS’ for the previous two years to the journal Science. They included casualties from all parties to the conflict:

The numbers show that 2,537 Afghans civilians were killed and 5,594 were wounded in the past two years. Most of the deaths – 80 percent – are attributed to insurgents, with 12 percent caused by coalition forces, a 26 percent drop.

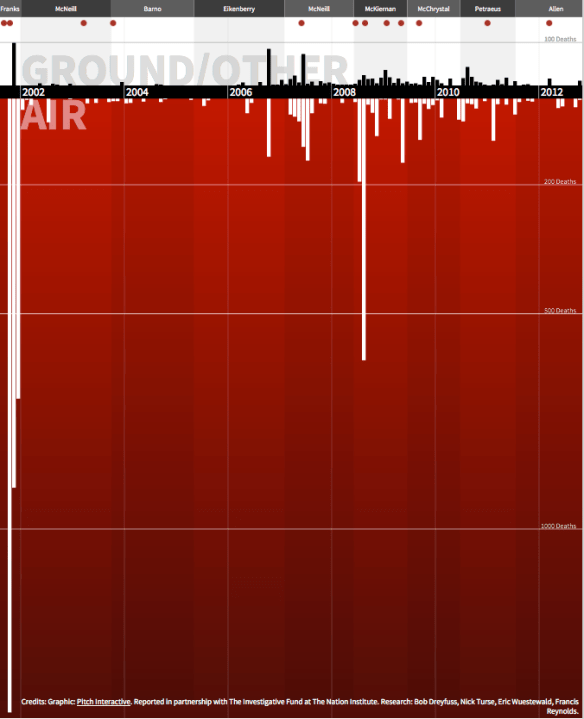

Here is Science‘s visualization of the CIVCAS data, designed to capture the time-space rhythms of violence from multiple causes:

You can access the interactive version here.

But other sources (notably the Afghan Rights Monitor and the UN Mission in Afghanistan, UNAMA, which produces six-monthly Reports on the protection of civilians in armed conflict) using different methodologies came up with much higher figures; here is a graph from the most recent UNAMA report showing casualties from air strikes 2009-13:

UNAMA added this comment:

UNAMA welcomes the reduction in civilian casualties from aerial operations but reiterates its concern regarding several operations that caused disproportionate loss of civilian life and injury. UNAMA also raises concerns with the lack of transparency and accountability about several aerial operations carried out by international military forces that resulted in civilian casualties.

You can find the full analysis by John Bohannon, which includes a discussion of both databases, at Science (open access) here.

To be sure, counting casualties is always a contentious (and often dangerous) affair. Getting information from the government of Afghanistan isn’t any more straightforward, as Nick Turse has shown: as he adds, ‘neither is it cheap’. But he persevered, and the wonderful Pitch Interactive (a data visualization studio that also produced the haunting representation of deaths from drone strikes in Pakistan) collaborated with The Nation to produce a stunning interactive of ‘civilian deaths that have occurred in Afghanistan as a result of war-related actions by the United States, its allies and Afghan government forces.’ Here’s a screenshot:

You will see running along the top the military commanders during each period; the red dots mark major events. It’s common knowledge – or should be – that the US-led invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 was spearheaded by an intensive high-level bombing campaign (I described this in The Colonial Present), shown along that desperately deep left margin. But I suspect fewer people have grasped the reliance that ISAF has continued to place on air power. What stands out from the image above, clearly, is the disproportionate (sic) number of deaths attributed to air strikes (5, 622) compared with ground operations (794) throughout the period: the UNAMA data above suggest that this only started to change in 2013. You can read more about this in the essay by Bob Dreyfuss and Nick Turse that accompanied the interactive, ‘America’s Afghan victims’, here, and – as always – the tireless work of Marc Herold is indispensable.

And to forestall a stream of comments, my title is not intended to suggest that digital technologies or the airstrikes they facilitate are somehow ‘immaterial’; nothing could be further from the truth. Or the killing fields.