This morning the Stimson Center issued an 81-page Recommendations and Report of the Task Force on US Drone Policy: you can access it online via the New York Times here or download it as a pdf here; Mark Mazetti‘s report for the Times is here.

Founded in 1989, the Stimson Center is a Washington-based ‘non-profit and non-partisan’ think-tank that prides itself on providing ’25 years of pragmatic solutions to global security’. It’s named after Henry Stimson, who served Presidents Taft, Roosevelt and Truman as Secretary of War and President Hoover as Secretary of State. The Center established its 10-member Task Force on drones a year ago, with retired General John Abizaid (former head of US Central Command, 2003-2007) and Rosa Brooks (Professor of Law at Georgetown) as co-chairs; the Task Force was aided by three Working Groups – on Ethics and Law; Military Utility, National Security and Economics; and Export Control and Regulatory Challenges – each of which is preparing more detailed reports to be published later this year. The present Report focuses on

‘key current and emerging issues relating to the development and use of lethal UAVs outside the United States for national security purposes. In particular, we focus extensively on the use of UAVs for targeted counterterrorism strikes, for the simple reason that this has generated significant attention, controversy and concern.’

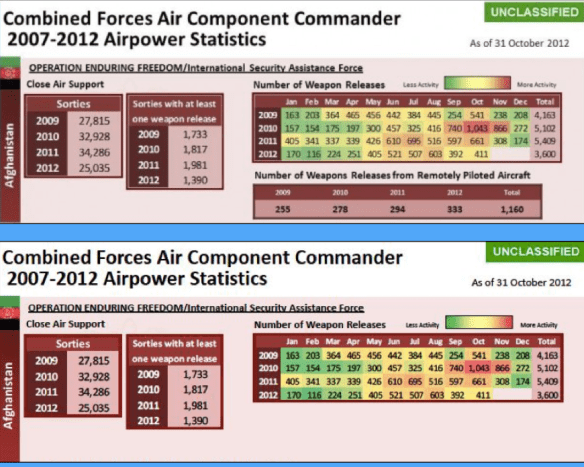

But this focus repeats and compounds the myopia of both conventional wisdom and contemporary debate. The Report summarily (and I think properly) rejects a number of misconceptions about the use of drones, insisting that their capacity to strike from a distance is neither novel nor unique; noting that the vast majority of UAVs in the US arsenal are non-weaponized (‘less than 1 percent of … UAVs carry operational weapons at any given time’ – though their intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance functions are of course closely tied to the deployment of weapons by conventional strike aircraft or ground forces); and arguing that ‘UAVs do not turn killing into “a video game”‘. These counter-claims are unexceptional and the Task Force presents them with clarity and conviction.

But the Report also accepts that the integration of UAVs into later modern war on ‘traditional’ or ‘hot’ battlefields [more about those terms in a moment] is, by and large, unproblematic. Thus:

‘UAVs have substantial value for a wide range of military and intelligence tasks. On the battlefield, both weaponized and non-weaponized UAVs can protect and aid soldiers in a variety of ways. They can be used for reconnaissance purposes, for instance, and UAVs also have the potential to assist in the detection of chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear weapons, as well as ordinary explosives. Weaponized UAVs can be used to provide close air support to soldiers engaged in combat.’

A footnote expands on that last sentence:

‘In the past, warfighters on the ground under imminent threat would have to navigate a complicated command hierarchy to call for air support. The soldier on the ground would have to relay coordinates to a Forward Air Controller (FAC), who would then talk the pilot’s eyes onto a target in an extremely hostile environment. These missions have always been very dangerous for the pilot, who has to fly low and avoid multiple threats, and also for people on the ground. It is a human-error rich environment, and even today, it is not uncommon for the wrong coordinates to be relayed, resulting in the deaths of friendlies or innocent civilians. To ease these difficulties, DARPA is currently investigating how to replace the FAC and the pilot by a weaponized UAV that will be commanded by the soldier on the ground with a smartphone.’

And subsequently the Report commends the ‘robust’ targeting process put in place by the US military and the incorporation of military lawyers (JAGs) into the kill-chain:

‘The Department of Defense has a robust procedure for targeting, with outlined authorities and steps, and clear checks on individual targets. The authorization of a UAV strike by the military follows the traditional process in place for all weapons systems (be they MQ-9 Reaper drones or F-16 fighter jets). Regardless of whether particular strikes are acknowledged, the Pentagon has stated that UAV strikes, like strikes from manned aircraft, are subject to the military’s pre-strike target development procedures and post-strike assessment.

‘The process of determining and executing a strike follows a specific set of steps to ensure fidelity in target selection, strike and post-strike review.’

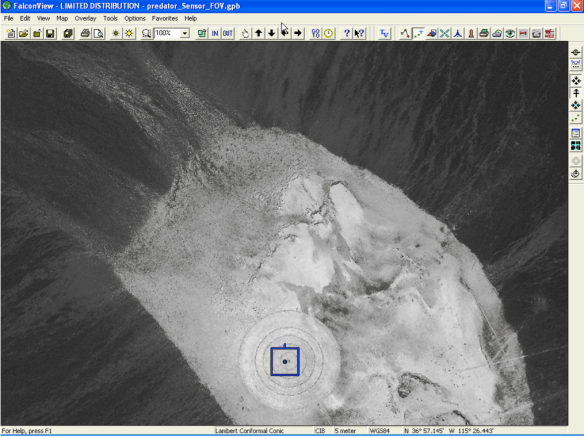

Both Craig Jones and I have discussed the targeting cycle [the figure above shows one of six steps in the ‘find-fix-track-target-engage-assess’ cycle, taken from JP 3-60 on Joint Targeting, issued in January 2013] and the role of operational law within it (Craig in much more detail than me), and these are all important considerations. But the Report glosses over the fragilities of the process, which in practice is not as ‘robust’ as the authors imply. They concede:

‘No weapons system is perfect, and targeting decisions — whether for UAV strikes or for any other weapons delivery system — are only as good as the intelligence on which they are based. We do not doubt that some US UAV strikes have killed innocent civilians. Nonetheless, the empirical evidence suggests that the number of civilians killed is small compared to the civilian deaths typically associated with other weapons delivery systems (including manned aircraft).’

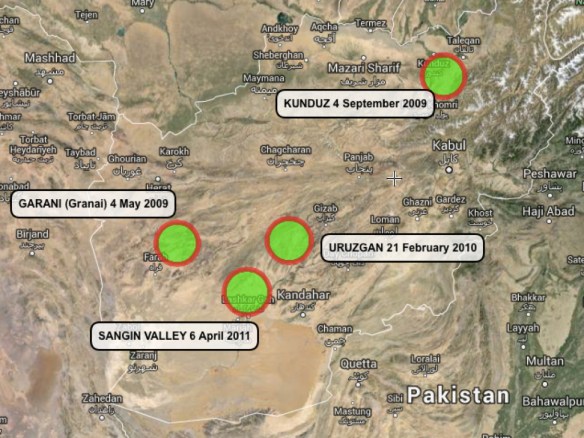

That last sentence is not unassailable, but in addition I’ve repeatedly argued that it is a mistake to abstract strikes carried out by UAVs from the wider network of military violence in which their ISR capabilities are put to use: hence my ongoing work on the Uruzgan airstrike in Afghanistan, for example, and on ‘militarised vision’ more generally. What these studies confirm is that civilian casualties are far more likely when close air support is provided – by UAVs directly or by conventional strike aircraft – to ‘troops in contact’ (even more so when, as in both the Kunduz and Uruzgan airstrikes, it turns out that troops calling in CAS were not ‘in contact’ at all).

That last sentence is not unassailable, but in addition I’ve repeatedly argued that it is a mistake to abstract strikes carried out by UAVs from the wider network of military violence in which their ISR capabilities are put to use: hence my ongoing work on the Uruzgan airstrike in Afghanistan, for example, and on ‘militarised vision’ more generally. What these studies confirm is that civilian casualties are far more likely when close air support is provided – by UAVs directly or by conventional strike aircraft – to ‘troops in contact’ (even more so when, as in both the Kunduz and Uruzgan airstrikes, it turns out that troops calling in CAS were not ‘in contact’ at all).

In short, while it’s perhaps understandable that a Task Force that included both General Abizaid and Lt-Gen David Barno (former head of Combined Forces Command – Afghanistan from 2003-2005) should regard the use of UAVs on ‘traditional’ battlefields as unproblematic, I think it regrettable that their considerable expertise did not result in a more searching evaluation of remote operations in Afghanistan and Iraq.

But what, then, of those ‘non-traditional’ battlefields? A footnote explains:

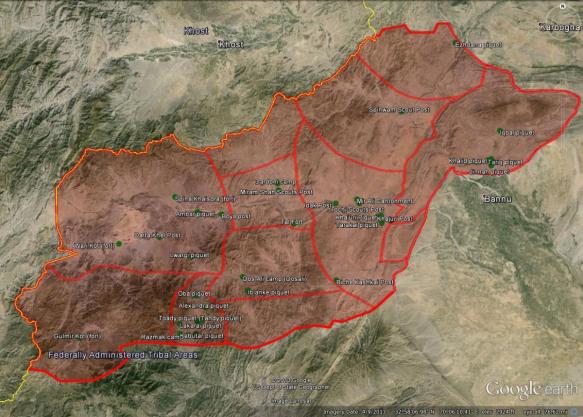

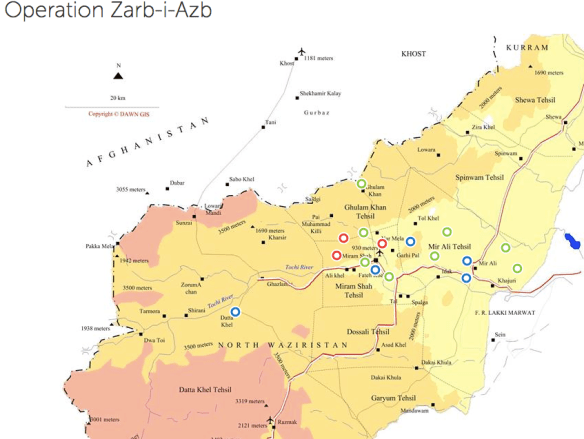

‘Throughout this report, we distinguish between the use of UAV strikes on “traditional” or “hot” battlefields and their use in places such as Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia. These are terms with no fixed legal meaning; rather, they are merely descriptive terms meant to acknowledge that the US of UAV strikes has not been particularly controversial when it is ancillary to large-scale, open, ongoing hostilities between US or allied ground forces and manned aerial vehicles, on the one hand, and enemy combatants, on the other. In Afghanistan and Iraq, the United States deployed scores of thousands of ground troops and flew a range of close air support and other aerial missions as part of Operation Enduring Freedom, and UAV strikes occurred in that context. In Libya, US ground forces did not participate in the conflict, but US manned aircraft and UAVs both operated openly to destroy Libyan government air defenses and other military targets during a period of large scale, overt ground combat between the Qaddafi regime and Libyan rebel groups. In contrast, the use of US UAV strikes in Yemen, Pakistan and elsewhere has been controversial precisely because the strikes have occurred in countries where there are no US ground troops or aerial forces openly engaged in large scale combat.’

A major focus of the report is on what Frédéric Mégret (above) has called ‘the deconstruction of the battlefield‘ and the countervailing legal geographies that provide an essential armature for later modern war (though it’s surprising that the Report makes so little use of academic research on UAVs and contemporary conflicts). The authors ‘disagree with those critics who have declared that US targeted killings [in Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia] are “illegal”’ – no surprise there either, incidentally, since one of the Working Groups included Kenneth Anderson, Charles Dunlap and Christine Fair: I’m not sure in what universe that counts as ‘non-partisan’) but they also accept that these remote operations move in a grey zone (and in the shadows):

‘The law of armed conflict and the international legal rules governing the use of force by states arose in an era far removed from our own. When the Geneva Conventions of 1949 were drafted, for instance, it was assumed that most conflicts would be between states with uniformed, hierarchically organized militaries, and that the temporal and geographic boundaries of armed conflicts would be clear.

‘The paradigmatic armed conflict was presumed to have a clear beginning (a declaration of war) and a clear end (the surrender of one party, or a peace treaty); it was also presumed the armed conflict to be confined geographically to specific, identifiable states and territories. What’s more, the law of armed conflict presumes that it is a relatively straightforward matter to identify “combatants” and distinguish them from “civilians,” who are not targetable unless they participate directly in hostilities. The assumption is that it is also a straightforward matter to define “direct participation in hostilities.”

‘The notion of “imminent attack” at the heart of international law rules relating to the use of force in state self-defense was similarly construed narrowly: traditionally, “imminent” was understood to mean “instant, overwhelming, and leaving no choice of means, and no moment for deliberation.”

‘But the rise of transnational non-state terrorist organizations confounds these preexisting legal categories. The armed conflict with al-Qaida and its associated forces can, by definition, have no set geographical boundaries, because al-Qaida and its associates are not territorially based and move easily across state borders. The conflict also has no temporal boundaries — not simply because we do not know the precise date on which the conflict will end, but because there is no obvious means of determining the “end” of an armed conflict with an inchoate, non-hierarchical network.

‘In a conflict so sporadic and protean — a conflict with enemies who wear no uniforms, operate in secret and may not use traditional “weapons” — the process of determining where and when the law of armed conflict applies, who should be considered a com- batant and what counts as “hostilities” inevitably is fraught with difficulty…

‘While the legal norms governing armed conflicts and the use of force look clear on paper, the changing nature of modern conflicts and security threats has rendered them almost incoherent in practice. Basic categories such as “battlefield,” “combatant” and “hostilities” no longer have a clear or stable meaning. And when this happens, the rule of law is threatened.’

These too are important considerations, but they are surely not confined to counter-terrorism operations in Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia: they also apply with equal force to counterinsurgency operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, and intersect with a wider and much more fraught debate over the very idea of ‘the civilian’.

There is a particularly fine passage in the Report:

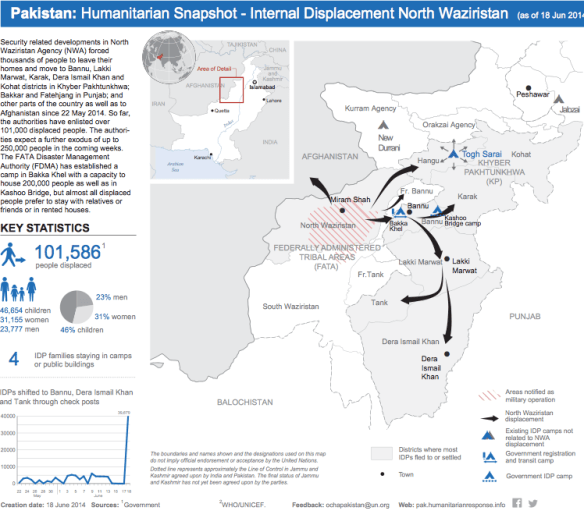

‘Consider US targeted strikes from the perspective of individuals in — for instance — Pakistan or Yemen. From the perspective of a Yemeni villager or a Pakistani living in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), life is far from secure. Death can come from the sky at any moment, and the instability and incoherence of existing legal categories means that there is no way for an individual to be certain whether he is considered targetable by the United States. (Would attending a meeting or community gathering also attended by an al-Qaida member make him targetable? Would renting a building or selling a vehicle to a member of an “associated” force render him targetable? What counts as an “associated force?” Would accepting financial or medical aid from a terrorist group make him a target? Would extending hospitality to a relative who is affiliated with a terrorist group lead the United States to consider him a target?).

‘From the perspective of those living in regions that have been affected by US UAV strikes, this uncertainty makes planning impossible, and makes US strikes appear arbitrary. What’s more, individuals in states such as Pakistan or Yemen have no ability to seek clarification of the law or their status from an effective or impartial legal system, no ability to argue that they have been mistakenly or inappropriately targeted or that the intelligence that led to their inclusion on a “kill list” was flawed or fabricated, and no ability to seek redress for injury. Their national laws and courts can offer no assistance in the face of foreign power, and far from protecting their fundamental rights and freedoms, their own states may in fact be deceiving them about their knowledge of and cooperation with US strikes. Meanwhile, geography and finances make it impossible to access US courts, and a variety of legal barriers — such as the state secrets privilege, the political question doctrine, and issues of standing, ripeness and mootness — in any case would prevent meaningful access to justice.’

This is one of the clearest summaries of the case for transparency and accountability I’ve seen, but the same scenario has also played out in Afghanistan (and in relation to the Taliban, which appears only once in the body of the Report) time and time again. There are differences, to be sure, but the US military has also carried out its own targeted killings in Afghanistan, working from its Joint Prioritized Effects List. The Report notes that ‘in practice, the military and CIA generally work together quite closely when planning and engaging in targeted UAV strikes: few strikes are “all military” or “all CIA”’ – which is true in other senses too – and this applies equally in Afghanistan.

In sum, then, this is a valuable and important Report – but it would have been far more incisive had its critique of ‘US drone policy’ cast its net wider to provide a more inclusive account of remote operations. The trans-national geographies of what I’ve called ‘the everywhere war’ do not admit of any simple distinction between ‘traditional’ and ‘non-traditional’ battlefields, and trying to impose one on such a tangled field of military and paramilitary violence ultimately confuses rather than clarifies. I realise that this is usually attempted as an exercise in what we might call legal cartography, but I also still think William Boyd‘s Gabriel was right when, in An Ice-Cream War, he complained that maps give the world ‘an order and reasonableness’ it doesn’t possess. And we all also know that maps – like the law – are instruments of power, and that both are intimately entangled with the administration of military violence.

Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer writes to say that his review of Grégoire Chamayou‘s Théorie du drone has just appeared in English translation over at Books & Ideas here.

Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer writes to say that his review of Grégoire Chamayou‘s Théorie du drone has just appeared in English translation over at Books & Ideas here.