This is the 11th in a series of extended posts on Grégoire Chamayou‘s Théorie du drone and covers the first two of three chapters that constitute Part III: Necro-ethics.

The title recalls Achille Mbembe‘s seminal essay on ‘Necropolitics’ [Public culture 15 (1) (2003) 11-40], where he cuts the umbilical cord between sovereignty and the state (and supranational institutions) and, inspired by Michel Foucault and Giorgio Agamben, argues that ‘the ultimate expression of sovereignty resides, to a large degree, in the power and the capacity to dictate who may live and who must die.’ Necropolitics is thus about ‘contemporary forms of subjugation of life to the power of death’ – and at the limit the creation of what Mbembe calls ‘death-worlds’.

Mbembe develops his thesis in part – and for good reason – in relation to the Israeli occupation of Palestine. I imagine readers will know that the Israeli Defence Force (IDF) advertises itself, incredibly, as ‘the most moral army in the world’, and although Chamayou’s ultimate objectives are different he too begins with a critical interrogation of one version of that claim (you can find much more about it in Muhammad Ali Khalidi‘s fine essay on Gaza in the Journal of Palestine Studies 39 (3) (2010) available on open access here).

1: Combatant immunity

Chamayou argues that what distinguishes contemporary forms of imperial military violence is not so much the asymmetry of the conflict or the differential distribution of vulnerability which results as the norms that are invoked to regulate its conduct. Towards the end of the twentieth century, he suggests, the ‘quasi-invulnerability’ of the dominant force was transformed into an over-arching politico-ethical framework. This first came into view during NATO’s intervention in Kosovo in 1999 when force protection was established as the key consideration: not only was the NATO campaign largely confined to bombing from the air (so that, apart from Special Forces, there were few boots – and, more to the point, NATO bodies – on the ground) – but pilots were ordered not to fly below 15,000 feet. This kept them safely beyond the range of anti-aircraft fire, even as it reduced the accuracy of air strikes and endangered the lives of those the intervention was supposed to save.

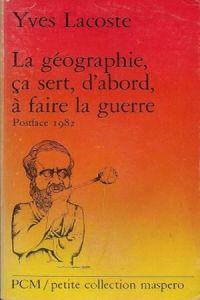

This seems to violate conventional notions of a just or ethical war, effectively turning ‘humanitarian intervention’ on its head, but Chamayou claims that in fact it heralded the explicit formulation of a principle of ‘imperial combatant immunity’. Enter the IDF, stage right. This new doctrine was set out in detail in an essay by Asa Kasher and Amos Yadlin, writing from the ‘Department of Professional Ethics and Philosophy of Practice’ at Tel Aviv University and the IDF College of National Defense, and published as ‘Military ethics of fighting terror: an Israeli perspective’, Journal of military ethics 4 (1) (2005) 3-32. As their affiliation shows, this was not an abstract, academic discussion; Chamayou notes, in an artful twist on Yves Lacoste (La géographie, ça sert, d’abord, à faire la guerre), ‘What use is moral philosophy? Among other things, to wage war…’ (‘A quoi sert la philosophie morale? Entre autres choses, à faire la guerre’) (p. 184).

In that essay Kasher and Yadlin proposed a comprehensive reformulation of military ethics – and, by extension, international law – but Chamayou fastens on their reworking (or demolition) of the established principle of distinction. He cites their central thesis, thus:

One major issue is the priority given to the duty to minimize casualties among the combatants of the state when they are engaged in combat acts against terror. According to the ordinary conception underlying the distinction between combatants and noncombatants, the former have a lighter package of state duties than the latter. Consequently, the duty to minimize casualties among combatants during combat is last on the list of priorities or next to last, if terrorists are excluded from the category of noncombatants. We reject such conceptions, because we consider them to be immoral. A combatant is a citizen in uniform. In Israel, quite often he is a conscript or on reserve duty. His blood is as red and thick as that of citizens who are not in uniform. His life is as precious as the life of anyone else. A democratic state may send him to a battlefront only because it has a duty to defend its citizens and it cannot do this without some of them defending the others, within the framework of a just system of conscription and reserve duty. The state ought to have a compelling reason for jeopardizing a citizen’s life, whether or not he or she is in uniform. The fact that persons involved in terror are depicted as noncombatants is not a reason for jeopardizing the combatant’s life in their pursuit. He has to fight against terrorists because they are involved in terror. They shoulder the responsibility for their encounter with the combatant and should therefore bear the consequences.

(It turns out that there are limits to the privileges accorded to citizen-soldiers: more recently Ha’aretz reports that Kasher suggested in early 2012 that medical experiments can be carried out on them, even if they are not fully informed of the details, in order to ‘build the military force’, though Kasher has contested these accusations and insisted that his opinion stipulated a series of ‘conditions’ that had to be met).

I didn’t mention Lacoste casually, because part of Kasher and Yadlin’s argument turns on territory: on the duties imposed by belligerent occupation (‘when a person resides in a territory that is under effective control of the state’). This is a Trojan Horse, needless to say, because they clearly have Gaza in their sights, and their proposal seeks to further the egregious fiction that Israel’s ‘withdrawal’ in 2005 meant that the Palestinians effectively imprisoned in Gaza are no longer subject to Israeli occupation (for more on ‘Gaza under siege’, see here). Chamayou doesn’t dwell on this, but the emphasis on ‘effective control’ could – if you accept Kasher and Yadlin’s grotesque argument (which they insist is a general one) – be brought to bear on the US campaign of targeted killing in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan, in Yemen and in Somalia and be made to intersect with the usual rhetoric about ‘ungoverned spaces’ and ‘lawless zones’.

Kasher and Yadlin summarize their proposed hierarchy of privileges by setting out a tariff according to which militaries would administer injury in priority sequence:

(d.1) Minimum injury to the lives of citizens of the state who are not combatants during combat;

(d.2) Minimum injury to the lives of other persons (outside the state) who are not involved in terror, when they are under the effective control of the state;

(d.3) Minimum injury to the lives of the combatants of the state in the course of their combat operations;

(d.4) Minimum injury to the lives of other persons (outside the state) who are not involved in terror, when they are not under the effective control of the state;

(d.5) Minimum injury to the lives of other persons (outside the state) who are indirectly involved in terror acts or activities;

(d.6) Injury as required to the liberties or lives of other persons (outside the state) who are directly involved in terror acts or activities.

Chamayou concludes that the core principle they seek to advance involves replacing the distinction between civilians and combatants by a hierarchical distinction between citizens and aliens: an unbridled nationalism masquerading as ethics (p. 187). In other words, within the frontier of state control – Chamayou says ‘ state sovereignty’, but that’s not quite what Kasher and Yadlin say – some lives are more precious than others, while beyond that line inferior lives (including those of what they call ‘bystanders’) are to be exposed to violence and ultimately sacrificed: as they put it, ‘the state should give priority to saving the life of a single citizen, even if the collateral damage caused in the course of protecting that citizen is much higher…’

Their proposals had a slow fuse but they eventually set off a firestorm of protest. Responding to a shorter version of the main essay [‘Assassination and preventive killing’, SAIS Review of International Affairs 25 (1) (2005) 41-57] and writing in the New York Review of Books (14 May 2009), Avishai Margalit and Michael Walzer were unequivocally appalled:

Their proposals had a slow fuse but they eventually set off a firestorm of protest. Responding to a shorter version of the main essay [‘Assassination and preventive killing’, SAIS Review of International Affairs 25 (1) (2005) 41-57] and writing in the New York Review of Books (14 May 2009), Avishai Margalit and Michael Walzer were unequivocally appalled:

‘Their claim, crudely put, is that in such a war the safety of “our” soldiers takes precedence over the safety of “their” civilians. Our main contention is that this claim is wrong and dangerous. It erodes the distinction between combatants and noncombatants, which is critical to the theory of justice in war (jus in bello).’

They continued:

‘The point of just war theory is to regulate warfare, to limit its occasions, and to regulate its conduct and legitimate scope. Wars between states should never be total wars between nations or peoples. Whatever happens to the two armies involved, whichever one wins or loses, whatever the nature of the battles or the extent of the casualties, the two nations, the two peoples, must be functioning communities at the war’s end. The war cannot be a war of extermination or ethnic cleansing. And what is true for states is also true for state-like political bodies such as Hamas and Hezbollah, whether they practice terrorism or not. The people they represent or claim to represent are a people like any other.

The main attribute of a state is its monopoly on the legitimate use of violence. Fighting against a state is fighting against the human instruments of that monopoly—and not against anyone else….

The crucial means for limiting the scope of warfare is to draw a sharp line between combatants and noncombatants. This is the only morally relevant distinction that all those involved in a war can agree on. We should think of terrorism as a concerted effort to blur this distinction so as to turn civilians into legitimate targets. When fighting against terrorism, we should not imitate it.’

In contrast,

‘For Kasher and Yadlin, there no longer is a categorical distinction between combatants and noncombatants. But the distinction should be categorical, since its whole point is to limit wars to those—only those—who have the capacity to injure (or who provide the means to injure)….

‘This is the guideline we advocate: Conduct your war in the presence of noncombatants on the other side with the same care as if your citizens were the noncombatants. A guideline like that should not seem strange to people who are guided by the counterfactual line from the Passover Haggadah, “In every generation, a man must regard himself as if he had come out of Egypt.”

Their critique found vigorous support from Menahem Yaari, a theoretical economist whose work has addressed (amongst other things) questions of justice, uncertainty and risk, but who wrote in a subsequent issue (8 October 2009) in his capacity as President of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities:

Their critique found vigorous support from Menahem Yaari, a theoretical economist whose work has addressed (amongst other things) questions of justice, uncertainty and risk, but who wrote in a subsequent issue (8 October 2009) in his capacity as President of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities:

‘A military code of conduct that discriminates, in cases of hazards being inflicted upon innocent civilians, on the basis of whether these civilians are “ours” or “theirs” is all the more worrisome when viewed against a general background of growing ethnocentric and xenophobic attitudes in Israel’s traditional establishment. We see an ongoing drift from universalism and humanism toward parochialism and tribalism.’

Picking up from that last sentence, Chamayou believes that this drift has accelerated and that it is by no means confined to Israel’s ‘traditional establishment’. In his view, the ‘evisceration’ of the core principles of international humanitarian law by a ‘nationalism of self-preservation’ has become ‘the primary guiding principle of the necro-ethics of the drone’ (p. 189).

2: Humanitarian weapon

Chamayou seeks to trace a line of descent from the previous arguments to those advanced more recently by academics who directly address (and defend) the US use of drones. He has two men in mind: Avery Plaw, an Associate Professor of Political Science at UMass – Dartmouth, and Bradley Jay Strawser, an Assistant Professor of Philosophy in the Defense Analysis Department at the US Naval Postgraduate School at Monterey.

Plaw has collaborated with several colleagues to track and evaluate drone strikes in Pakistan and is involved in the UMass DRONE project (I’ve commented on this before), but it’s an Op-Ed in the New York Times on 14 November 2012 that catches Chamayou’s attention. ‘Drones save lives, American and others’ was the headline, and Chamayou is bemused: ‘How can an instrument of death save lives?’

The question seems to invite a biopolitical response – ‘killing in order to let live’, as Mbembe and others would no doubt have it, and Chamayou doesn’t quite provide that – but neither does Plaw quite say what the headline implies. He suggests that ‘drone strikes are the best way to remove an all-too-real threat to American lives’ and that ‘there is evidence that drone strikes are less harmful to civilians than other means of reaching Al Qaeda and affiliates in remote, lawless regions’. Perhaps this amounts to the same thing, but it’s not quite the cold calculus that Chamayou attributes to Plaw. And as I read his (brief) intervention, the ‘American lives’ that Plaw sees as being at risk are not those of, say, ground troops in Afghanistan but of civilians in the continental United States threatened by attacks from al-Qaeda and its affiliates – though even then Plaw would have to explain how they are ‘saved’ by attacks on the Taliban and other militant groups which scarcely pose a trans-continental danger.

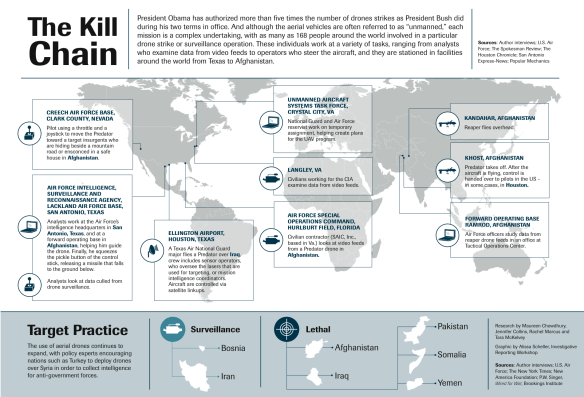

In any event, Chamayou challenges what he sees as the paradoxically vitalist claim that serves as the first principle of contemporary necro-ethics: drones are ‘humanitarian’ because they save lives – and specifically ‘our’ lives (p. 192), which he sees encapsulated even more succinctly than in Plaw’s Op-Ed by the tag-line in the image above (from Popular Science in November 1997): ‘Nobody dies – except the enemy.’

This is where he turns to – and on – Strawser. Like Plaw, he has had his views publicised in the media –see Rory Carroll on ‘The philosopher making the moral case for US drones’ in the Guardian here and Strawser’s hasty qualification here – but Chamayou directs his attention to Strawser’s essay ‘Moral Predators: the duty to employ uninhabited aerial vehicles’, Journal of military ethics 9 (4) (2010) 342-68. More recently, by the way, he’s edited a collection of essays, Killing by remote control: the ethics of an unmanned military (Oxford University Press, 2013), which includes an essay by Plaw on ‘Counting the dead: the proportionality of predation in Pakistan’ and an exchange between Kasher and Plaw, in which the (I think substantial) differences between the two are clarified. These centre on the principle of distinction: the requirement to discriminate between combatants and civilians. Kasher makes no secret of what he calls his ‘negative attitude to the principle of distinction as it is commonly understood and practically applied’ (which doesn’t leave much room for a positive attitude). ‘Humanitarian’, he insists, means ‘an attitude towards human beings as such, not toward a certain group of people’ – given the way in which the IDF treats Palestinians, this strikes me as pretty thick – so that the principle of distinction is really ‘civilarian’ (his term) and fails to respect ‘the human dignity of combatants in the broad sense of men and women in uniform’ (which isn’t a ‘broad sense’ at all, of course: Kasher’s combatants all wear uniform). ‘A democratic state [sic] owes its citizens in military uniform a special justification for jeopardizing their life when they do it not for the relatively simple reason of defending their fellow citizens,’ he argues, ‘but when they are required to do it for the sake of saving the life of enemy citizens who are not combatants.’ The recourse to drones, he concludes, ‘circumvents such difficulties’.

This is where he turns to – and on – Strawser. Like Plaw, he has had his views publicised in the media –see Rory Carroll on ‘The philosopher making the moral case for US drones’ in the Guardian here and Strawser’s hasty qualification here – but Chamayou directs his attention to Strawser’s essay ‘Moral Predators: the duty to employ uninhabited aerial vehicles’, Journal of military ethics 9 (4) (2010) 342-68. More recently, by the way, he’s edited a collection of essays, Killing by remote control: the ethics of an unmanned military (Oxford University Press, 2013), which includes an essay by Plaw on ‘Counting the dead: the proportionality of predation in Pakistan’ and an exchange between Kasher and Plaw, in which the (I think substantial) differences between the two are clarified. These centre on the principle of distinction: the requirement to discriminate between combatants and civilians. Kasher makes no secret of what he calls his ‘negative attitude to the principle of distinction as it is commonly understood and practically applied’ (which doesn’t leave much room for a positive attitude). ‘Humanitarian’, he insists, means ‘an attitude towards human beings as such, not toward a certain group of people’ – given the way in which the IDF treats Palestinians, this strikes me as pretty thick – so that the principle of distinction is really ‘civilarian’ (his term) and fails to respect ‘the human dignity of combatants in the broad sense of men and women in uniform’ (which isn’t a ‘broad sense’ at all, of course: Kasher’s combatants all wear uniform). ‘A democratic state [sic] owes its citizens in military uniform a special justification for jeopardizing their life when they do it not for the relatively simple reason of defending their fellow citizens,’ he argues, ‘but when they are required to do it for the sake of saving the life of enemy citizens who are not combatants.’ The recourse to drones, he concludes, ‘circumvents such difficulties’.

Similarly, though not identically, Strawser regards the drone as not simply a morally permissible weapon but rather as a morally compulsory one. He proposes a Principle of Unnecessary Risk , according to which ‘it is wrong to command someone to take on unnecessary potentially lethal risks in an effort to carry out a just action for some good’, and then extrapolates more or less directly to the compulsion to employ Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs):

‘We have a duty to protect an agent engaged in a justified act from harm to the greatest extent possible, so long as that protection does not interfere with the agent’s ability to act justly. UAVs afford precisely such protection. Therefore, we are obligated to employ UAV weapon systems if it can be shown that their use does not significantly reduce a warfighter’s operational capability.’

Strawser then qualifies his basic Principle: ‘the just warrior’s increased protection (which a UAV provides) should not be bought at an increased risk to noncombatants.’ In effect, Chamayou argues, Strawser makes Kasher and Yadlin’s principle of self-preservation subordinate to the minimisation of risks to non-combatants. But when Strawser insists that ‘if using a UAV in place of an inhabited weapon platform in anyway whatsoever decreases the ability to adhere to jus in bello principles [of proportionality and distinction], then a UAV should not be used,’ Chamayou believes he is also playing his ‘get out of jail free’ card. For Strawser claims that ‘there is good reason to think just the opposite is true: that UAV technology actually increases a pilot’s ability to discriminate’. In support, Strawser cites an Israeli pilot –

‘The beauty of this seeker is that as the missile gets closer to the target, the picture gets clearer . . .The video image sent from the seeker via the fiber-optic link appears larger in our gunner’s display. And that makes it much easier to distinguish legitimate from non-legitimate targets’

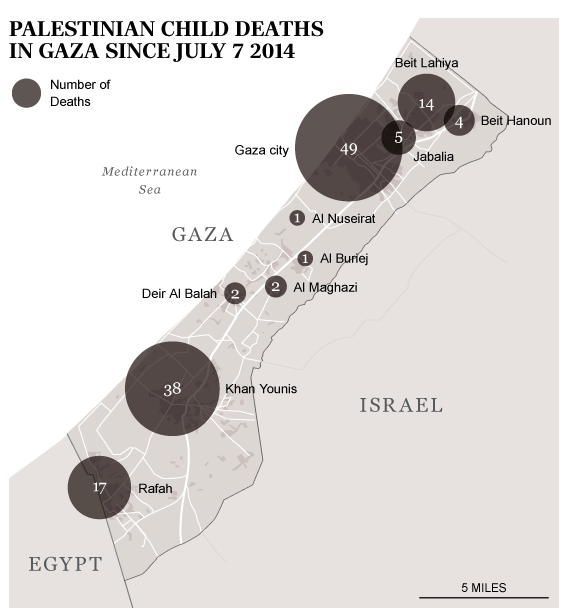

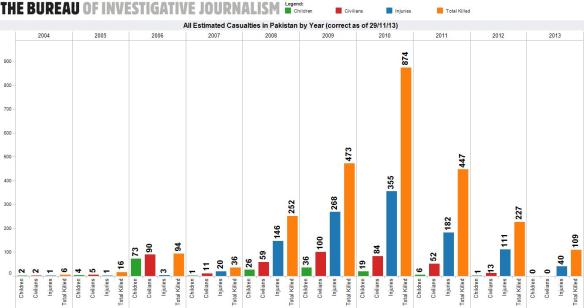

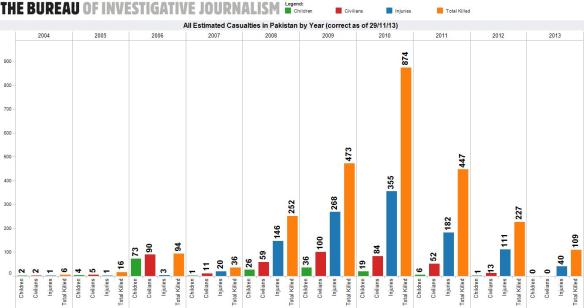

– and Plaw’s analysis of drone strikes in Pakistan from 2004 to 2007. Strawser concedes that the claim for enhanced distinction is an empirical one; Plaw’s analysis needs a fuller examination than I can provide in this post, but it’s important to note that 2007 is a significant cut-off. As the chart below shows, from the splendid Bureau of Investigative Journalism, this is long before the Obama administration ramped up the attacks on the Federally Administered Tribal Areas. Plaw’s chapter in Killing by remote control extends his analysis to 2011 and concludes that US drone strikes – particularly when weighed against casualties from insurgent attacks or Pakistan military operations in the region – most often meet the demands of proportionality; but the discussion doesn’t directly address discrimination.

What Strawser does, Chamayou concludes, is offer a technical resolution of an ethical dilemma: it is not necessary to subordinate one principle to another – minimisation of risk to combatants (‘citizen-soldiers’) or minimisation of risk to non-combatants (‘alien’ or otherwise) – because this new technology of killing promises to satisfy both. In effect, drones are supposed to introduce a new, intrinsically ethical symmetry to asymmetric warfare: they save ‘our’ lives and ‘their’ lives. They combine the power to kill and to save, to wound and to care, a weapon at once humanitarian and military – ‘humilitaire’, as Chamayou has it. (Others have made a case for the humanitarian uses of unarmed drones, but their arguments are a far cry from military applications).

Yet if this new military power saves lives, Chamayou demands, what is it saving them from? His answer: from itself, from its own power to kill. And if this seems the lesser evil, in Eyal Weizman‘s terms the ‘result of a field of calculations that seeks to compare, measure and evaluate different bad consequences’, then we need to remind ourselves, with Hannah Arendt, how quickly ‘those who choose the lesser evil forget … that they chose evil.’

Chamayou turns to Weizman deliberately; that ‘field of calculations’, the calculus that is focal to the construction through calibration of our ‘humanitarian present’, is the target of Chamayou’s next and final chapter in his critique of necro-ethics – of which more very soon.

UPDATE: Today’s Guardian has a video debate between Seumas Milne and Peter Lee (Portsmouth University): ‘Is the use of unmanned military drones ethical or criminal?’ Lee claims that, ‘used correctly’, this new technology and in particular the MQ-9 Reaper is ‘the most potentially ethical use of air power yet devised.’