Before I resume my reading of Grégoire Chamayou‘s Théorie du drone, I want to approach his thesis from a different direction. As I’ve noted, much of his argument turns on the reduction of later modern war to ‘man-hunting’: the profoundly asymmetric pursuit of individuals by activating the hunter-killer capacities of the Predator or the Reaper in a new form of networked (para)military violence. He describes this as a ‘state doctrine of non-conventional violence’ that combines elements of military and police operations without fully corresponding to either: ‘hybrid operations, monstrous offspring [enfants terribles] of the police and the military, of war and peace’.

Before I resume my reading of Grégoire Chamayou‘s Théorie du drone, I want to approach his thesis from a different direction. As I’ve noted, much of his argument turns on the reduction of later modern war to ‘man-hunting’: the profoundly asymmetric pursuit of individuals by activating the hunter-killer capacities of the Predator or the Reaper in a new form of networked (para)military violence. He describes this as a ‘state doctrine of non-conventional violence’ that combines elements of military and police operations without fully corresponding to either: ‘hybrid operations, monstrous offspring [enfants terribles] of the police and the military, of war and peace’.

These new modalities increase the asymmetry of war – to the point where it no longer looks like or perhaps even qualifies as war – because they preclude what Joseph Pugliese describes as ‘“a general system of exchange” [the reference is to Achille Mbembe’s necropolitics] between the hunter-killer apparatus ‘and its anonymous and unsuspecting victims, who have neither a right of reply nor recourse to judicial procedure.’

Pugliese insists that drones materialise what he calls a ‘prosthetics of law’, and the work of jurists and other legal scholars provides a revealing window into the constitution of later modern war and what, following Michael Smith, I want to call its geo-legal armature. To date, much of this discussion has concerned the reach of international law – the jurisdiction of international law within (Afghanistan) and beyond (Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia) formal zones of conflict – and the legal manoeuvres deployed by the United States to sanction its use of deadly force in ‘self-defence’ that violates the sovereignty of other states (which includes both international law and domestic protocols like the Authorization for the Use of Military Force and various executive orders issued after 9/11) . These matters are immensely consequential, and bear directly on what Frédéric Mégret calls ‘the deconstruction of the battlefield’.

It’s important to understand that the ‘battlefield’ is more than a physical space; it’s also a normative space – the site of ‘exceptional norms’ within whose boundaries it is permissible to kill other human beings (subject to particular codes, rules and laws). Its deconstruction is not a new process. Modern military violence has rarely been confined to a champ de mars insulated from the supposedly safe spaces of civilian life. Long-range strategic bombing radically re-wrote the geography of war. This was already clear by the end of the First World War, and in 1921 Giulio Douhet could already confidently declare that

It’s important to understand that the ‘battlefield’ is more than a physical space; it’s also a normative space – the site of ‘exceptional norms’ within whose boundaries it is permissible to kill other human beings (subject to particular codes, rules and laws). Its deconstruction is not a new process. Modern military violence has rarely been confined to a champ de mars insulated from the supposedly safe spaces of civilian life. Long-range strategic bombing radically re-wrote the geography of war. This was already clear by the end of the First World War, and in 1921 Giulio Douhet could already confidently declare that

‘By virtue of this new weapon, the repercussions of war are no longer limited by the farthest artillery range of guns, but can be felt directly for hundreds and hundreds of miles… The battlefield will be limited only by the boundaries of the nations at war, and all of their citizens will become combatants, since all of them will be exposed to the aerial offensives of the enemy. There will be no distinction any longer between soldiers and civilians.’

The laboratory for these experimental geographies before the Second World War was Europe’s colonial (dis)possessions – so-called ‘air control’ in North Africa, the Middle East and along the North-West Frontier – but colonial wars had long involved ground campaigns fought with little or no distinction between combatants and civilians.

What does seem to be novel about more recent deconstructions, so Mégret argues, is ‘a deliberate attempt to manipulate what constitutes the battlefield and to transcend it in ways that liberate rather than constrain violence.’

This should not surprise us. Law is not a deus ex machina that presides over war as impartial tribune. Law, Michel Foucault reminds us, ‘is born of real battles, victories, massacres and conquests’; law ‘is born in burning towns and ravaged fields.’ Today so-called ‘operational law’ has incorporated military lawyers into the kill-chain, moving them closer to the tip of the spear, but law also moves in the rear of military violence: in Eyal Weizman’s phrase, ‘violence legislates.’ In the case that most concerns him, that of the Israel Defense Force, military lawyers work in the grey zone between ‘the black’ (forbidden) and ‘the white’ (permitted) and actively seek to turn the grey into the white: to use military violence to extend the permissive envelope of the law.

This should not surprise us. Law is not a deus ex machina that presides over war as impartial tribune. Law, Michel Foucault reminds us, ‘is born of real battles, victories, massacres and conquests’; law ‘is born in burning towns and ravaged fields.’ Today so-called ‘operational law’ has incorporated military lawyers into the kill-chain, moving them closer to the tip of the spear, but law also moves in the rear of military violence: in Eyal Weizman’s phrase, ‘violence legislates.’ In the case that most concerns him, that of the Israel Defense Force, military lawyers work in the grey zone between ‘the black’ (forbidden) and ‘the white’ (permitted) and actively seek to turn the grey into the white: to use military violence to extend the permissive envelope of the law.

The liber(alis)ation of violence that Mégret identifies transforms the very meaning of war. In conventional wars combatants are authorised to kill on the basis of what Paul Kahn calls their corporate identity:

‘…the combatant has about him something of the quality of the sacred. His acts are not entirely his own….

‘The combatant is not individually responsible for his actions because those acts are no more his than ours…. [W]arfare is a conflict between corporate subjects, inaccessible to ordinary ideas of individual responsibility, whether of soldier or commander. The moral accounting for war [is] the suffering of the nation itself – not a subsequent legal response to individual actors.’

The exception, Kahn continues, which also marks the boundary of corporate agency, is a war crime, which is ‘not attributable to the sovereign body, but only to the individual.’ Within that boundary, however, the enemy can be killed no matter what s/he is doing (apart from surrendering). There is no legal difference between killing a general and killing his driver, between firing a missile at a battery that is locking on to your aircraft and dropping a bomb on a barracks at night. ‘The enemy is always faceless,’ Kahn explains, ‘because we do not care about his personal history any more than we care about his hopes for the future.’ Combatants are vulnerable to violence not only because they are its vectors but also because they are enrolled in the apparatus that authorizes it: they are killed not as individuals but as the corporate bearers of a contingent (because temporary) enmity.

It is precisely this model that contemporary military violence now challenges through the prosthetics of law embodied and embedded in drone warfare – and this, Kahn insists, has transformed the political imaginary of warfare (You can find his full argument here: ‘‘Imagining warfare’, European journal of international law 24 (1) (2013) 199-216).

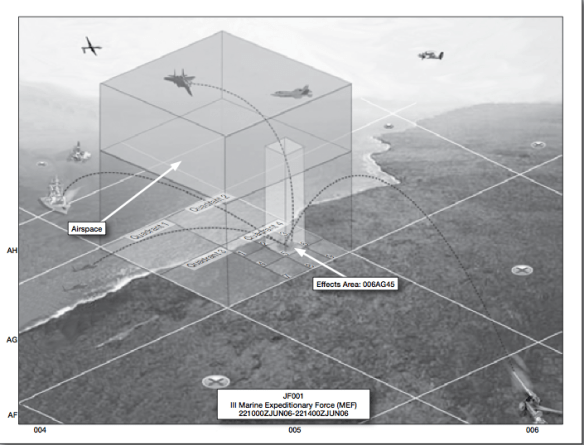

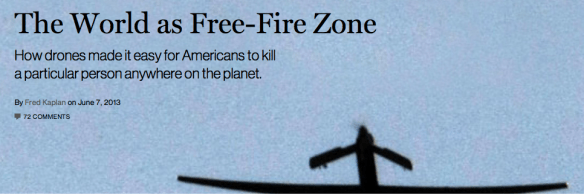

In a parallel argument, Samuel Issacharoff and Richard Pildes describe this development as the individuation of military force, driven in part by the affordances and dispositions of drone warfare which makes it possible to put ‘warheads on foreheads.’ Targets are no longer whole areas of cities – like Cologne or Hamburg in the Second World War – or extensive target boxes like those ravaged by B-52 ‘Arc Light’ strikes over the rainforest of Vietnam. The targets are individuals and, since the United States claims the right to target them wherever they are found, this partly explains the dispersed geography of what I’ve called ‘the everywhere war’. What interests Issacharoff and Pildes, like Kahn, is not so much the technology that makes this possible as the apparatus that makes it permissible.

Their presentation wavers uncertainly between counterinsurgency and counter-terrorism, and they also write more generally of ‘the new face of warfare’ and the use of ‘military force’, so that (as now happens in practice) the distinctions between the US military and the CIA become blurred. But their core argument is that military force is now directed against specific individuals on the basis of determinate acts that they have committed or, by pre-emptive extension, are likely to commit. In Kahn’s terms, this inaugurates a radically different (though in his eyes, highly unstable) political subjectivity through which the enemy is transformed into the criminal. ‘The criminal is always an individual,’ Kahn explains; ‘the enemy is not.’

For Issacharoff and Pildes this new state of affairs requires an ‘adjudicative apparatus’ to positively identify, detect and prosecute the individual-as-target, which drives the military system ever closer to the judicial system:

‘As the fundamental transformation in the practice of the uses of military force moves, even implicitly, toward an individuated model of responsibility, military force inevitably begins to look justified in similar terms to the uses of punishment in the criminal justice system. That is, to the extent that someone can be targeted for the use of military force (capture, detention, killing) only because of the precise, specific acts in which he or she as an individual participated, military force now begins to look more and more like an implicit “adjudication” of individual responsibility.’

They suggest that this makes it inevitable that the boundaries between the military system and the judicial system ‘will become more permeable’ – a confirmation of the active constitution of the war/police assemblage (on which see Colleen Bell, Jan Bachmann and Caroline Holmqvist’s forthcoming collection, The New Interventionism: perspectives on war-police assemblages).

Kahn is, I think, much more troubled by this than Issacharoff and Pildes. He concludes (like Chamayou):

‘Political violence is no longer between states with roughly symmetrical capacities to injure each other; violence no longer occurs on a battlefield between masses of uniformed combatants; and those involved no longer seem morally innocent. The drone is both a symbol and a part of the dynamic destruction of what had been a stable imaginative structure. It captures all of these changes: the engagement occurs in a normalized time and space, the enemy is not a state, the target is not innocent, and there is no reciprocity of risk. We can call this situation ‘war’, but it is no longer clear exactly what that means.

‘The use of drones signals a zone of exception to law that cannot claim the sovereign warrant. It represents statecraft as the administration of death. Neither warfare nor law enforcement, this new form of violence is best thought of as the high-tech form of a regime of disappearance. States have always had reasons to eliminate those who pose a threat. In some cases, the victims doubtlessly got what they deserved. There has always been a fascination with these secret acts of state, but they do not figure in the publicly celebrated narrative of the state. Neither Clausewitz nor Kant, but Machiavelli is our guide in this new war on terror.’

He is thoroughly alarmed at the resuscitation of what he calls ‘the history of administrative death’, whereas Issacharoff and Pildes – ironically, given what I take to be their geopolitical sympathies –treat the institution and development of an ‘adjudicative apparatus’ within the US programme of targeted killings as a vindication of their execution (sic).

I want to set aside other contributions to the emerging discussion over the ‘individuation’ of warfare – like Gabriella Blum‘s depiction of an ‘individual-centred regime’ of military conduct, which pays close attention to its unstable movement between nationalism and cosmopolitanism – in order to raise some questions about the selectivity of ‘individuation’ as a techno-legal process. I intend that term to connote three things.

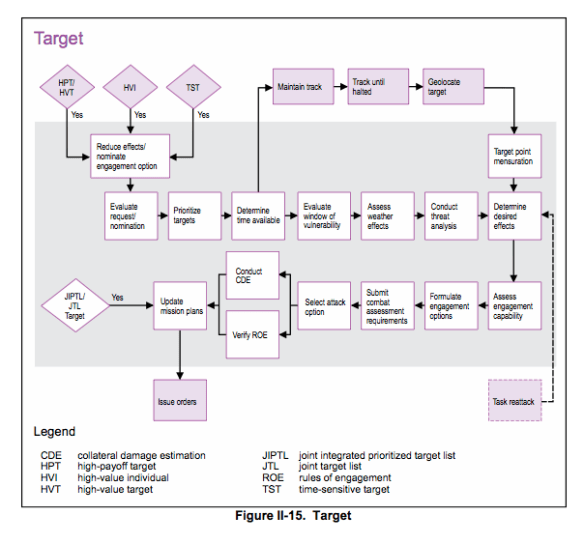

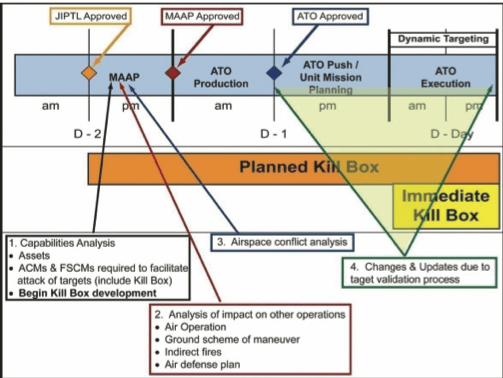

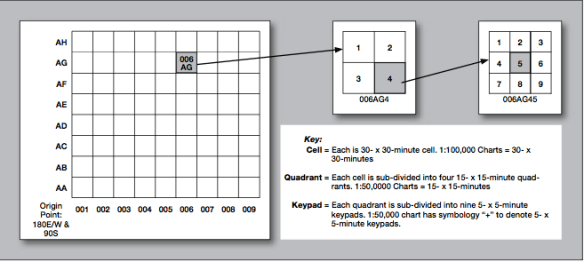

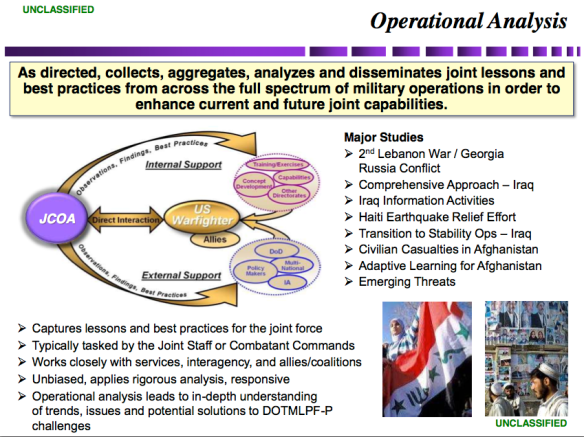

(1) First, and most obviously, Issacharoff and Pildes fasten on the technical procedures that have been developed to administer targeted killings – which include both the ‘disposition matrix’ [see here] and its derivatives and the more directly instrumental targeting cycle [the diagram above shows the ‘Target’ phase of the Find-Fix-Track-Target-Engage-Assess cycle] , both of which admit legal opinions and formularies – that convert targeted killing into what Adi Ophir calls a quasi-juridical process. This encoding works to contract the ethical horizon to the legal-juridical (see here for a critical commentary) while simultaneously diverting attention from the substantive practice – which, as I showed in ‘Lines of descent’ (DOWNLOADS tab), is shot through with all sorts of limitations that confound the abstract calculations of the targeting cycle (see, for example, Gregory McNeal here, who turns ‘accountability’ into accountancy).

(2) Second, ‘individuation’ refers to the production of the individual as a technical artefact of targeting. S/he is someone who is apprehended as a screen image and a network trace; s/he may be named in the case of a ‘personality strike’ but this serves only as an identifier in a target file, and the victims of ‘signature strikes‘ are not accorded even this limited status. Others who are killed in the course of the strike almost always remain unidentified by those responsible for their deaths – ‘collateral damage’ whose anonymity confirms on them no individuality but only a collective ascription. (For more, see Thomas Gregory, ‘Potential lives, impossible deaths: Afghanistan, civilian casualties and the politics of intelligibility’, International Feminist Journal of Politics 14 (3) (2012) 327-47; and ‘Naming names’ here).

(3) Third, the adjudication of ‘individual responsibility’ bears directly on the production of the target but not, so it seems, on the producers of the target. Lucy Suchmann captures this other side – ‘our’ side – in a forthcoming essay in Mediatropes (‘Situational awareness: deadly bioconvergence at the boundaries of bodies and machines’):

‘A corollary to the configuration of “their” bodies as targets to be killed is the specific way in which “our” bodies are incorporated into war fighting assemblages as operating agents, at the same time that the locus of agency becomes increasingly ambiguous and diffuse. These are twin forms of contemporary bioconvergence, as all bodies are locked together within a wider apparatus characterized by troubling lacunae and unruly contingencies.’

Caroline Holmqvist, sharpens the same point in ‘Undoing war: war ontologies and the materiality of drone warfare’, Millennium (1 May 2013) d.o.i. 10.1177/0305829813483350); so too, and more directly relevant to the operations of a techno-legal process, does Joseph Pugliese‘s figure of drone crews as ’embodied prostheses of the law of war grafted on to their respective technologies’.

These various contributions identify a dispersion of responsibility across the network in which the drone crews are embedded and through which they are constituted. The technical division of labour is also a social division of labour – so that no individual bears the burden of killing another individual – but the social division of labour is also a technical division of labour through which ‘agency’ is conferred upon what Pugliese calls its prostheses:

‘Articulated in this blurring of lines of accountability is a complex network of prostheticised and tele-techno mediated relations and relays that can no longer be clearly demarcated along lines of categorical divisibility: such is precisely the logic of the prosthetic. As the military now attempts to grapple with this prostheticised landscape of war, it inevitably turns to technocratic solutions to questions of accountability concerning lethal drone strikes that kill the wrong targets.’

If the mandated technical procedures (1 above) fail to execute a sanctioned target (2 above) and if this triggers an investigation, the typical military response is to assign responsibility to the improper performance of particular individuals (which protects the integrity of the process) and/or to technical malfunctions or inefficiencies in the network and its instruments (which prompts technical improvements). What this does not do – is deliberately designed not to do – is to probe the structure of this ‘techno-legal economy of war at a distance’ (Pugliese’s phrase) that turns, as I’ve tried to suggest, on a highly particular sense of individuation. Still less do these inquiries disclose the ways in which, to paraphrase Weizman, ‘drones legislate’ by admitting or enrolling into this techno-legal economy particular subjectivities and forcefully excluding others .

More to come.

***

Note: Here are the citations for Issacharoff and Pildes’ full argument(s); the first is excerpted from the second, which deals with ‘capture’ (detention) as well as killing:

Samuel Issacharoff and Richard Pildes, ‘Drones and the dilemma of modern warfare’, in Peter Bergen and Daniel Rothenberg (eds) Drone wars: the transformation of armed conflict and the promise of law (Cambridge University Press, 2013); available here as NYU School of Law, Public Law & Legal Theory Research Paper Series Working Paper No. 13-34, June 2013

Samuel Ischaroff and Richard Pildes, ‘Targeted warfare: individuating enemy responsibility’, NYU School of Law, Public Law & Legal Theory Working Papers 343 (April 2013); available here.