Breaking the Silence has just published a major report into the Israeli military’s tactics during its most recent offensive against Gaza and its people, so-called ‘Operation Protective Edge’ (see my posts here, here, here and here).

Based on interviews with 65 IDF soldiers, the report includes Background, Testimonies (‘This is how we fought in Gaza‘), and a media gallery.

Writing in today’s Guardian, Peter Beaumont reports:

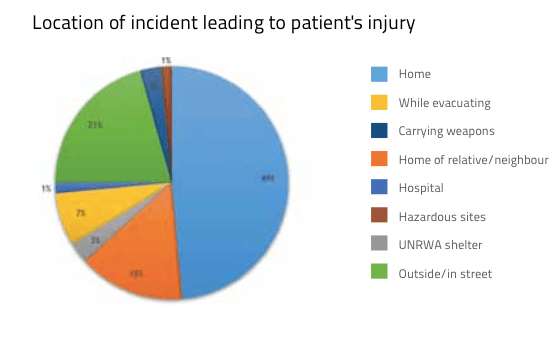

Describing the rules that meant life and death in Gaza during the 50-day war – a conflict in which 2,200 Palestinians were killed – the interviews shed light for the first time not only on what individual soldiers were told but on the doctrine informing the operation.

Despite the insistence of Israeli leaders that it took all necessary precautions to protect civilians, the interviews provide a very different picture. They suggest that an overarching priority was the minimisation of Israeli military casualties even at the risk of Palestinian civilians being harmed….

Post-conflict briefings to soldiers suggest that the high death toll and destruction were treated as “achievements” by officers who judged the attrition would keep Gaza “quiet for five years”.

The tone, according to one sergeant, was set before the ground offensive into Gaza that began on 17 July last year in pre-combat briefings that preceded the entry of six reinforced brigades into Gaza.

“[It] took place during training at Tze’elim, before entering Gaza, with the commander of the armoured battalion to which we were assigned,” recalled a sergeant, one of dozens of Israeli soldiers who have described how the war was fought last summer in the coastal strip.

“[The commander] said: ‘We don’t take risks. We do not spare ammo. We unload, we use as much as possible.’”

“The rules of engagement [were] pretty identical,” added another sergeant who served in a mechanised infantry unit in Deir al-Balah. “Anything inside [the Gaza Strip] is a threat. The area has to be ‘sterilised,’ empty of people – and if we don’t see someone waving a white flag, screaming: “I give up” or something – then he’s a threat and there’s authorisation to open fire … The saying was: ‘There’s no such thing there as a person who is uninvolved.’ In that situation, anyone there is involved.”

“The rules of engagement for soldiers advancing on the ground were: open fire, open fire everywhere, first thing when you go in,” recalled another soldier who served during the ground operation in Gaza City. The assumption being that the moment we went in [to the Gaza Strip], anyone who dared poke his head out was a terrorist.”

You can find an impassioned, detailed commentary on the report by Neve Gordon – who provides vital context, not least about the asymmetric ethics pursued by supposedly ‘the most ethical army in the world’ – over at the London Review of Books here, and a shorter commentary by Kevin Jon Heller at Opinio Juris here. Kevin notes:

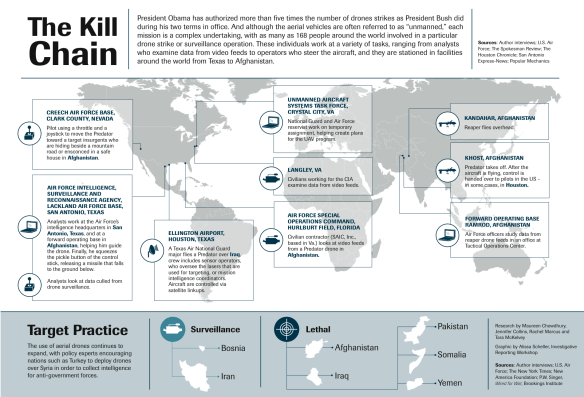

The soldiers’ descriptions are disturbingly reminiscent of the notorious “free fire” zones in Vietnam and the US government’s well-documented (and erroneous) belief that signature strikes directed against “military-age men in an area of known terrorist activity” comply with IHL’s principle of distinction. The testimonials are, in a word, stunning — and put the lie to oft-repeated shibboleths about the IDF being “the most moral army in the world.” As ever, the stories told by the IDF and the Israeli government are contradicted by the soldiers who actually have to do the killing and dying.

The legal and ethical framework pursued by the Israeli military – and ‘pursued’ is the mot (in)juste, since its approach to international law and ethics is one of aggressive intervention – is in full view at a conference to be held in Jerusalem this week: ‘Towards a New Law of War‘.

‘The goal of the law of war conference,’ say the organisers, ‘is to influence the direction of legal discourse concerning issues critical to Israel and her ability to defend herself. The law of war is mainly unwritten and develops on the basis of state practice.’

You can find the full program here, dominated by speakers from Israel and the US, but notice in particular the session on ‘Proportionality: Crossing the line on civilian casualties‘:

As this makes clear, and as Ben White reports in the Middle East Monitor, law has become the target (see also my post here):

After ‘Operation Cast Lead’, Daniel Reisner, former head of the international law division (ILD) in the Military Advocate General’s Office, was frank about how he hoped things would progress.

If you do something for long enough, the world will accept it. The whole of international law is now based on the notion that an act that is forbidden today becomes permissible if executed by enough countries….International law progresses through violations.

Similarly, in a “moral evaluation” of the 2008/’09 Gaza massacre, Asa Kasher, author of the IDF’s ‘Code of Ethics’, expressed his hope that “our doctrine” will ultimately “be incorporated into customary international law.” How?

The more often Western states apply principles that originated in Israel to their own non-traditional conflicts in places like Afghanistan and Iraq, then the greater the chance these principles have of becoming a valuable part of international law.

Now Israel’s strategy becomes clearer… Israel’s assault on the laws of war takes aim at the core, guiding principles in IHL – precaution, distinction, and proportionality – in order to strip them of their intended purpose: the protection of civilians during armed conflict. If successful, the victims of this assault will be in the Occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip, Lebanon – and in occupations and war zones around the world.