News from Lucy Suchman of a special issue of Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, and Technoscience on Digital Militarisms. Here is a list of the articles plus abstracts; all are available for download here (open access).

Configuring the Other: Sensing War through Immersive Simulation – Lucy Suchman

This paper draws on archival materials to read two demonstrations of FlatWorld, an immersive military training simulation developed between 2001 and 2007 at the University of Southern California’s Institute for Creative Technologies. The first demonstration is a video recording of a guided tour of the system, staged by its designers in 2005. The second is a documentary created by the US Public Broadcasting Service as part of their “embedded” media coverage of the system while it was installed at California’s Camp Pendleton in 2007. I critically attend to the imaginaries that are realized in the simulation’s figurations of places and (raced, gendered) bodies, as well as its storylines. This is part of a wider project of understanding how distinctions between the real and the virtual are effectively elided in technoscientific military discourses, in the interest of recognizing real/virtual entanglements while also reclaiming the differences that matter.

***

Military Utopias of Mind and Machine – Emily Cohen Ibañez

The central locus of my study is southern California, at the nexus of the Hollywood entertainment industry, the rapidly growing game design world, and military training medical R&D. My research focuses on the rise of military utopic visions of mind that involve the creation of virtual worlds and hyper-real simulations in military psychiatry. In this paper, I employ ethnography to examine a broader turn to the senses within military psychology and psychiatry that involve changes in the ways some are coming to understand war trauma, PTSD, and what is now being called “psychological resilience.” In the article, I critique assumptions that are made when what is being called “a sense of presence” and “immersion” are given privileged attention in military therapeutic contexts, diminishing the subjectivity of soldiers and reducing meaning to biometric readings on the surface of the body. I argue that the military’s recent preoccupation with that which can be described as “immersive” and possessing a sense of presence signals a concentrated effort aimed at what might be described as a colonization of the senses – a digital Manifest Destiny that envisions the mind as capital, a condition I am calling military utopias of mind and machine. Military utopias of mind and machine aspire to have all the warfare without the trauma by instrumentalizing the senses within a closed system. In the paper, I argue that such utopias of control and containment are fragile and volatile fantasies that suffer from the potential repudiation of their very aims. I turn to storytelling, listening, and conversations as avenues towards healing, allowing people to ascribe meaning to difficult life experiences, affirm social relationships, and escape containment within a closed language system.

***

Simulated War: Remediating Trauma Narratives in Military Psychotherapy – Marisa Renee Brandt

How have the politics of therapy been reconfigured during the so-called Global War on Terror? What role have the new virtual reality therapies that so resemble other forms of military simulation played in this reconfiguration? In this article, I draw upon feminist science and technology’s (STS) theorization of human-machine interaction into order to interrogate how contemporary therapies for treating post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) reconfigure agency in the practice of healing. Analyzing trauma therapy as a site of reconfiguration, I show how new exposure-based therapies for PTSD—both with and without virtual reality—configure aspects of human subjectivity, such as memory, affect, and behavior, as objects for technological intervention. Through comparative analysis of different modalities of PTSD treatment, I show that the politics of therapy is especially enacted through the therapeutic remediation of trauma narratives: the mediational practices through which a traumatic memory is made available for therapeutic reworking. Therapeutic remediation practices configure therapists, patients, and nonhuman actants as subjects and objects with different forms of agency.

***

Weaponizing Affect: A Film Phenomenology of 3D Military Training Simulations during the Iraq War – D. Andy Rice

This article critically considers the relation between simulation design and human experience through the analysis of three-dimensional military training simulation scenarios developed between 2003 and 2012 at the Fort Irwin National Training Center in the Mojave Desert of California. Following news reports of torture at Abu Ghraib, the US military began to implement “cultural awareness” training for all troops set to deploy to the Middle East. The military contracted with Hollywood special-effects studios to develop a series of counterinsurgency warfare immersive-training simulations, including hiring Iraqi-American and Afghan-American citizens to play villagers, mayors, and insurgents in scenarios. My primary question centers on the military technoscience of treating human bodies as variables in a reiterative simulation scenario. I analyze interviews with soldiers and actors, my own experiences videotaping training simulations at the fort, and the accounts of many other visiting journalists and filmmakers across time. From this, I contend that the stories participants tell about simulation experiences constitute one key outcome of the simulation itself, blunting dissent and aiding the fort’s long-term efforts to retain clout and funding in the face of wars whose intensity fluctuates. I treat the ongoing cinematic performances on the fort as a kind of “simulation body” unbounded by skin, a theoretical framework drawn from Vivian Sobchack’s (1992) film phenomenological concept of the “film body” and affect theory grounded in the work of Kara Keeling (2007), as well as Eve Sedgwick (2003), Sedgwick and Adam Frank (1995), and Lisa Cartwright (2008), by way of American behavioral psychoanalyst Silvan Tomkins (2008).

***

Tactical Tactility: Warfare, Gender, and Cultural Intelligence – Isra Ali

The participation of women in the landscape of warfare is increasingly visible; nowhere is this more evident than in the US military’s global endeavors. The US military’s reliance on cultural intelligence in its conceptualization of engagement strategies has resulted in the articulation of specific gendered roles in warfare. Women are thought to be particularly well suited to non-violent tactile engagements with civilians in war zones in Iraq and Afghanistan because of gender segregation in public and private spaces. Women in the military have consequently been able to argue for recognition of their combat service by framing this work in the war zone as work only women can do. Women reporters have been able to develop profiles as media producers, commentators, and experts on foreign policy, women, and the military by producing intimate stories about the lives of civilians only they can access. The work soldiers and reporters do is located in the warzone, but in the realms of the domestic and social, in the periods between bursts of violent engagement. These women are deployed as mediators between civilian populations in Afghanistan and Iraq and occupying forces for different but related purposes. Soldiers do the auxiliary work of combat in these encounters, reporters produce knowledge that undergirds the military project. Their work in combat zones emphasizes the interpersonal and relational as forms of tactile engagement. In these roles, they are also often mediating between the “temporary” infrastructure of the war zone and occupation, and the “permanent” infrastructure of nation state, local government, and community. The work women do as soldiers and reporters operates effectively with the narrative of militarism as a means for liberating women, reinforcing the perception of the military as an institution that is increasingly progressive in its attitudes towards membership, and in its military strategies. When US military strategy focuses on cultural practice in Arab and Muslim societies, commanders operationalize women soldiers in the tactics of militarism, the liberation of Muslim women becomes central in news and governmental discourses alike, and the notion of “feminism” is drawn into the project of US militarism in Afghanistan and Iraq in complex ways that elucidate how gender, equality, and difference, can be deployed in service of warfare.

***

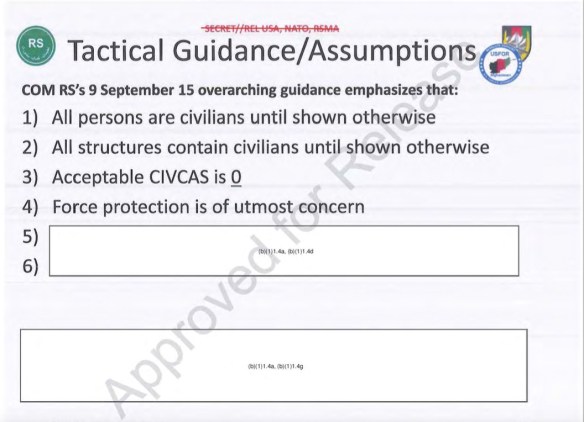

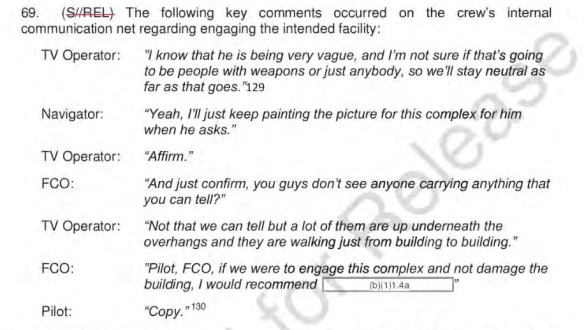

A Drone Manifesto: Re-forming the Partial Politics of Targeted Killing –Katherine Fehr Chandler

Debates about today’s unmanned systems explain their operation using binary distinctions to delimit “us” and “them,” “here” and “there,” and “human” and “machine.” Yet the networked actions of drone aircraft persistently undo these oppositions. I show that unmanned systems are dissociative, not dualistic. I turn to Haraway’s “A Cyborg Manifesto” (1991) to reflect on how drones rework limits ranging from the scale of bodies to geopolitical territories, as well as the political challenges they entail. The analysis has two parts. The first considers how Cold War drones fit into cybernetic discourse. I examine the Firebee, a pilotless target built in the aftermath of World War II, and explore how the system acts as if it were guided by machine responses even though human control remains integral to its operation. The second part considers how contemporary discussions of drone aircraft, both for and against the systems, rely on this dissociative logic. Rather than critiquing unmanned aircraft as dehumanizing, I argue that responses to drones must address the interconnections they produce and call for a politics that puts together the dissociations on which unmanned systems rely.

***

Introduction to Attachments to War: Violence and the Production of Biomedical Knowledge in Twenty-first Century America – Jennifer Terry

This is an excerpt from Jennifer Terry’s book, Attachments to War: Violence and the Production of Biomedical Knowledge in Twenty-first Century America, forthcoming 2017.