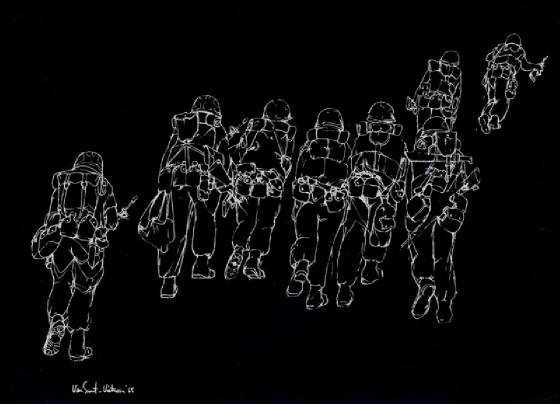

I’ve received several e-mails asking for “Boots on the Ground” to be continued. So here is the rest of my discussion of militarised nature in Vietnam, extracted from the long-form version of “The natures of war“. It follows on directly from that earlier post, but please bear in mind that this is still only a draft – in particular, I need to add a discussion of malaria, somehow, somewhere – and that I’ve excised the footnotes and references from this version.

***

Even the weather seemed out to get them. The tropical heat and humidity were so enervating that they appeared to possess their own monstrous agency. ‘There were moments when I could not think of it as heat,’ Caputo confessed, ‘rather it seemed to be a thing malevolent and alive.’ Dehydration and heatstroke were constant concerns, and the monsoon only compounded their misery. ‘It rained like it had been waiting ten thousand years to rain,’ one lieutenant said when the monsoon broke, and John Ketwig described rain drops ‘as large as marbles and driven with enough force to sting when they hit you.’ The ground was turned into a sea of mud, and even the ‘rear-echelon motherfuckers’ on the permanent bases had to contend with their bunkers and foxholes filling with water, and roads becoming ‘ribbons of churned slop’. Ketwig again:

‘There were areas of shallow mud and areas of deep mud, but there were no areas without mud. Most of our world was under water, and you had to know where to step. The huge trucks we worked with would often sink up to the frame. The driver would try four-wheel-drive, spin the cleated duals at the rear, and dig himself in deeper. The rule was, the driver who “lost” a truck had to swim down and attach the tow chains. Swim is an accurate term for the depth of the mud, but hardly describes the frenzied mucking about in zero-visibility goo.’

One Marine newly arrived at a base near the DMZ in the middle of the monsoon was advised that the best way to navigate the ‘boot sucking slurry’ was to ‘walk in the tank tracks’: ‘The mud is only an inch deep there … Plus if we take incoming [fire], you can lay down in the track and you’re five inches lower.’ Vietnam was often more than a metaphorical quagmire.

The irony was that the billowing storm clouds limited air reconnaissance and so made ground patrols all the more important. They also constrained the logistical and medical support that could be provided to them:

‘There were many days when aircraft could not fly in such all-consuming cloudy conditions. Hence we were not always assured that we would be re-supplied, or that we could get choppers in to take out our wounded or dead, and on one occasion we were compelled to sleep with our dead, and then awake in the morning and carry our dead along with us, while waiting for an opportunity to clear an LZ (landing zone) so that choppers could come in and lift our comrades out of the jungle for their final journey home.’

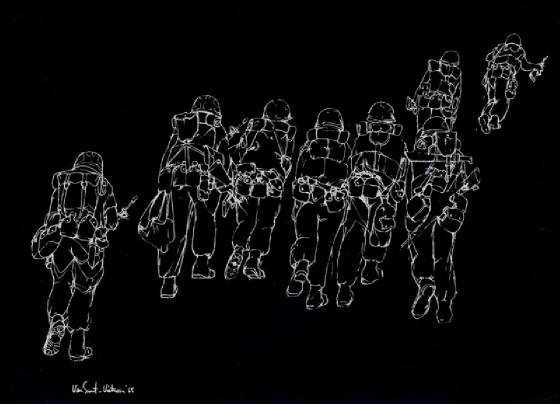

For those out beyond the wire the monsoon wreaked havoc. Jack Estes describes one tropical storm ‘ripping, ravaging and slapping through the jungle’ and ‘howling like a monstrous beast.’ Soldiers were drenched to the skin, their uniforms chafed, their packs became heavier as they absorbed the water, and thick, cloying mud clung to their boots and weighed down their every step. ‘The mud was ground into my letters’, wrote one Marine.

‘The mud was ground into everything. The mud was in our ears and mouths. Our c-rats [C-rations] tasted like the mud we lived in… We were brown men. Even the black men were brown men.’

It was all desperately invasive, and Lawrence said he felt ‘persistently violated by the soaking wetness’. There was no let-up when darkness fell and they dug in for the night. ‘Sleep was measured in minutes at a time on the rainy nights’ and ‘muscles were constantly drawn tight against the cold.’ One Marine admitted that one night it was so miserable that ‘after a while we were hugging like young lovers’ just to stay warm. But usually the combination of cold and wet was utterly debilitating.

‘The rain comes in sheets all through the night and when I am relieved I remain standing with the Marine that has relieved me. Soon we realize that nearly the entire team is standing to escape the flooded ground. As the rain intensifies, I surrender to the cold deluge; wrapping myself into the wet, muddy plastic, I try to sleep. Before daylight, I wake shivering and half submerged in a deep puddle of cold rainwater, the edges of my poncho floating beside me. I pray that I am dreaming. Leeches cover my legs, their bodies filled to the point of bursting, gorged with type “O” Positive. The crotch of my jungle trousers is caked with blood; a leech has fed on my groin. My wrinkled fingers struggle with the bottle of insect repellant and as I squirt it on their membrane-like skin, I vent my rage on them with frantic curses that are filled with disgust. As I watch them fall off in agony, I scratch at the wounds to maintain the flow of rich, clean blood that will hopefully prevent infection; the repellent burns deep into each wound.’

Aching muscles, pus-filled skin sores and scabs (‘jungle rot’) and even leeches were the least of their worries. The infantry still marched on its feet as well as its stomach – for the grunts at least, ‘the war was fought with the feet and legs’ – and constant immersion invited the return of an old adversary. When Delezen hauled off one of his soaking boots he was taken aback:

‘[T]he foot is a wrinkled mass of putrid milk-white flesh and is badly cracked and bleeding. With the ragged boot in one hand and my weapon in the other, I crawl through the matted bamboo to the Corpsman [Marine medical specialist]; after a quick glance he tells me that there is nothing that he can do, his feet are in the same condition. It is immersion foot; trench foot was what our grandfathers called it in France. One by one each of my teammates removes one boot at a time and stares in repulsion at the condition of their feet… I try to dry the foot but I have nothing that is not waterlogged. Finally, in desperation, I place the wet socks under the shoulder holster; perhaps my body heat will dry them. There is nothing more that I can do so I pull the muddy jungle boot back on, lace it up, and try to forget about my ravaged feet.’

‘[T]he foot is a wrinkled mass of putrid milk-white flesh and is badly cracked and bleeding. With the ragged boot in one hand and my weapon in the other, I crawl through the matted bamboo to the Corpsman [Marine medical specialist]; after a quick glance he tells me that there is nothing that he can do, his feet are in the same condition. It is immersion foot; trench foot was what our grandfathers called it in France. One by one each of my teammates removes one boot at a time and stares in repulsion at the condition of their feet… I try to dry the foot but I have nothing that is not waterlogged. Finally, in desperation, I place the wet socks under the shoulder holster; perhaps my body heat will dry them. There is nothing more that I can do so I pull the muddy jungle boot back on, lace it up, and try to forget about my ravaged feet.’

These physical sensations of exhaustion and pain were registered in a sensorium in which the usual hierarchy of senses was scrambled. As on the Western Front and in the Western Desert, sight was compromised in the rainforest. Visibility was limited by the dense vegetation and the filtered light. With a patrol strung out in single file five metres apart, it was all too easy to lose sight of the man in front – O’Brien said they each followed him ‘like a blind man after his dog’ – and at night ‘it was like walking inside a black velvet bag.’ Everyone’s eyes ached ‘from the constant strain of searching through the layers of jungle.’ In the middle of this ‘war of plant life’, wrote Caputo, ’it was difficult to see much of anything through the vines and trees, tangled together in a silent, savage struggle for light and air’. And yet, for that very reason, they had an almost palpable ‘sense of being surrounded by something we could not see.’ ‘It was the inability to see that vexed us most,’ he continued. ‘In that lies the jungle’s power to cause fear: it blinds.’ Not surprisingly, he concluded that ‘in Vietnam the best soldiers were unimaginative men.’ Once again, O’Brien spells out the consequences: ‘What we could not see, we imagined.’

As sight lost its primacy the other senses were heightened, particularly hearing. Noise was literally a dead giveaway – ‘sound was death in the jungle’ – and the jingle of equipment had to be minimised. Before setting out, Delezen explained, ‘each of us, donning our heavy equipment, jumps up and down listening attentively for the slightest sound; there can be no exception. What may be considered an insignificant rattle will become amplified in the silent bush.’ Sounds also seemed to travel farther at night. ‘Shortly after sunset the jungle became as black as tar, and our sense of hearing came to predominate over our sense of sight.’ Other noises filled the canopy – ‘the croaking of tree frogs, the clicking of gecko lizards like sticks of bamboo banging together, the drone of myriad insects, and the occasional screech of a monkey’ – and these played cruel tricks with the imagination. In isolation they could sound a false alarm, and it was common for rookies to wake their companions because they had heard something, only to be reassured ‘there was nothing out there.’ But together, as a sort of green noise, they could ‘lull you into somnambulance … [and] numb your sense of hearing and smell and sight until you start seeing things in the night.’

All of these burdens, physiological and psychological, convinced many soldiers that their greatest danger was from Nature itself. What exercised them most about the jungle was not the prospect of an encounter with a wild animal; their accounts mention bamboo vipers, whose bite was horribly painful but not deadly, and even the occasional tiger, but they repeatedly tell themselves that ‘all the bombing and artillery have driven the wildlife up into Cambodia.’ Neither was it the thought of being killed or wounded in an ambush: ‘Contact with the enemy was very sporadic’, John Nesser explained, and instead ‘it was the day-to-day miseries in the bush that got to us.’ It would be wrong to minimise the dangers of being killed or wounded, which surely preyed on soldiers’ minds. But what they clearly came to loathe with a passion was their intimate, intensely corporeal violation by the jungle itself. ‘There it is you motherfuckers,’ crows Corporal Jancowitz in Karl Marlantes’ Matterhorn: ‘Another inch of the green dildo.’ The image is part of a long tradition of ‘porno-tropicality’ that is hardly peculiar to the US military, but during the Vietnam war it has a particular resonance for what it implies about violence, masculinity and the ‘un-manning’ of American soldiers.

Its power turns on the militarisation of nature in an altogether different register: one in which the jungle becomes terrifyingly alive, and its militant agency is made to account for the degradation of soldiers caught in its poisonous embrace and to justify its own destruction. There is a scene in Stephen Wright’s Meditations in Green in which a photo-interpreter on a large US airbase is advised to sit on top of a bunker and stare at the jungle.

‘“You have to concentrate because if you blink or look away for even a moment you might miss it, they aren’t dumb despite what you may think, they’re clever enough to take only an inch or two at a time. The movement is slow but inexorable, irresistible, maybe finally unstoppable. A serious matter.”

‘“You have to concentrate because if you blink or look away for even a moment you might miss it, they aren’t dumb despite what you may think, they’re clever enough to take only an inch or two at a time. The movement is slow but inexorable, irresistible, maybe finally unstoppable. A serious matter.”

“What movement, what are you are you talking about?”

“The trees, of course, the fucking shrubs. And one day we’ll look up and there they’ll be, branches reaching in, jamming our M-60s, curling around our waists.”

“Like Birnam Wood, huh?”

“Actually, I was thinking more of triffids.”’

The scene is fiction but not entirely fanciful – one platoon leader called it ‘the magic hour when men begin to look like bushes, and bushes begin to move’ – and many came to see the jungle as capricious and even wilfully obstructive. Caputo complained that ‘cord-like “wait-a-minute” vines coiled around our arms, rifles and canteen tops with a tenacity that seemed almost human.’ A radio operator humped the set on his chest not his back because otherwise ‘the vines constantly change the frequency by spinning the knobs of the radio top.’ ‘Perhaps it is the bush that is the enemy’, wondered Delezen:

‘[T]he jungle is a “cat’s cradle” of twisted vines that seem alive, as if reaching for me. Sometimes, even when not moving, I find myself held in their grasp, it as if they silently attack when I am not looking, as though they are thinking organisms. When moving, the only way to pass through the vines is to become a vine; it is impossible to push through the jungle, forcing, fighting, and struggling. The bush must be negotiated with and each vine must be silently dealt with as an individual. Stealth and quiet is all that prevents our destruction from the ever-present enemy. We have learned that we must become a part of the bush, always searching for the passage that lies hidden through the entanglement…’

In this passage the young Marine moves from being attacked by the vines – ‘held in their grasp’ – to becoming one, ‘a part of the bush’, and the precarious relation between the two had to be constantly renegotiated if the men were to survive. ‘At times I am certain that it is possible for our team to be consumed by the enveloping walls of foliage,’ Delezen continues, ‘without a trace we could easily disappear forever, absorbed into the tangled mass.’ This was more than the spectral fear of getting lost, though that was ever present; more too than losing your grip in what O’Brien called ‘a botanist’s madhouse’. For many soldiers it was also an existential threat that emanated from a diabolical Nature. ‘The Puritan belief that Satan dwelt in Nature could have been born here,’ Herr wrote in an extraordinary passage:

‘Even on the coldest, freshest mountaintops you could smell jungle and that tension between rot and genesis that all jungles give off. It is ghost-story country… Oh, that terrain! The bloody, maddening uncanniness of it!’

Downs too was taken aback by the pervasive sensation of rot. ‘Covering everything was the smell of slimy, rotting vegetation’, he recalled. ‘Our clothes and our bodies were beginning the rotting process of the jungle.’ He recognised this as a physical danger – ‘every scratch was a breeding spot for bacteria which could result in the rapid growth of jungle rot’ – and one that involved constant physical degradation: as one Marine officer put it, ‘it is a different way to live, and it is not a state of grace.’ Downs also saw this as a profoundly moral danger. ‘Every day we spent in the jungle eroded a little more of our humanity away.’ For him and for countless others the rot set in as the deeply sedimented Enlightenment distinctions between nature and culture dissolved in the jungle. ‘Everything rotted and corroded quickly over there,’ Caputo agreed, ‘bodies, boot leather, canvas, morals’:

‘Scorched by the sun, wracked by the wind and rain of the monsoon, fighting in alien swamps and jungles, our humanity rubbed off of us as the protective bluing rubbed off the barrels of our rifles.’

To him, it was ‘an ethical as well as a geographical wilderness. Out there, lacking restraints, sanctioned to kill, confronted by a hostile country and a relentless enemy, we sank into a brutish state.’

Admissions like these reappear throughout the letters, diaries and memoirs that I have read, sometimes explicitly and sometimes implicitly (the cleansing shower when a patrol returns from the field can sometimes be more than a matter of physical hygiene). They invite questions about how far the imprecations of nature – its assault not only on the human body but also on the humanity of the soldier – functioned for some of them as a more or less unconscious alibi for atrocity, so that those who committed acts of indiscriminate or unnecessary violence believed they had somehow been reduced to a ‘state of nature’ by nature. Its plausibility must have been heightened by the common dehumanisation of the Vietnamese (‘gooks’) and the reduction of the enemy and the civilian population to creatures of nature. Bernd Greiner says as much in his detailed analysis of atrocities in the far north and south of Vietnam: ‘Nature, the elements, literally everything took on the form of the enemy.’

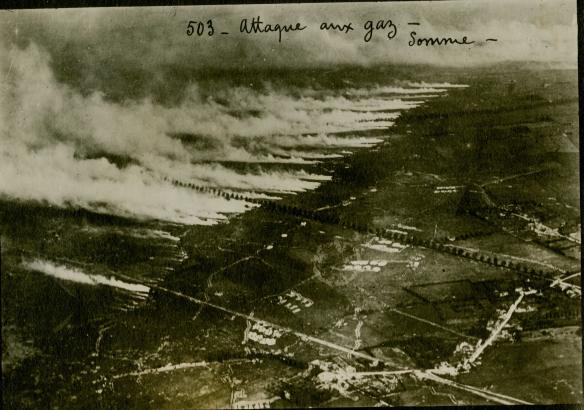

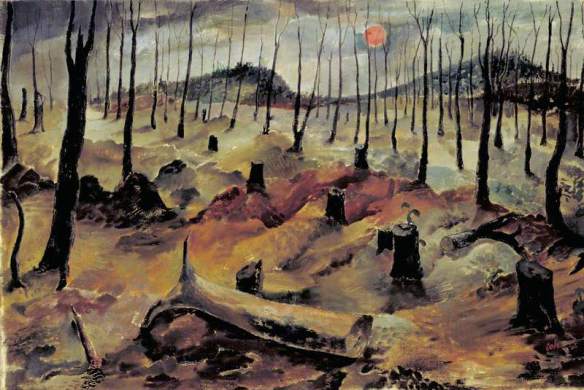

The same imaginary also licensed a war on nature. The B-52 strikes, the napalm and the artillery bombardments all shattered the landscape (and the lives of many of those within it) but, as Wright’s Griffin is told in Meditations in Green, ‘it’s not as if [the] bushes were innocent.’ Griffin’s job was to assess the effects of the spraying of Agent Orange on the rainforest, the mangroves and the paddy fields by examining time series of air photographs:

‘It was all special effects out there. Crops aged overnight, roots shrivelled, stalks collapsed where they stood into the common unmarked grave of poisoned earth. Trees turned in their uniforms, their weapons, and were mustered out, skeletal limbs too weak to assume the position of attention… Griffin sat on his stool and watched the land die around him.’

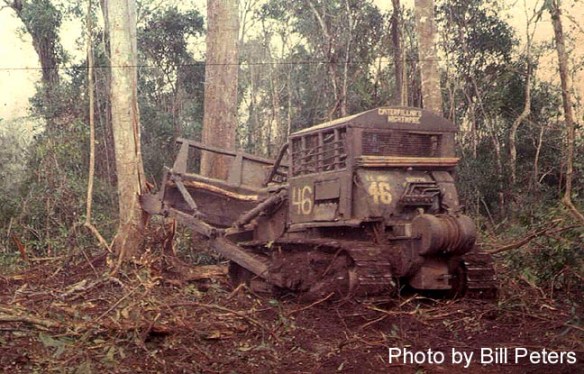

Wright was not alone in imaginatively enlisting the trees in the enemy’s battalions. This was the logic behind Operation Hades – a differently diabolical militarisation of nature – that was soon re-named Operation Ranch Hand. Its objective was to spray the forests with herbicides and deny their cover to the North Vietnamese Army and the Viet Cong. In so far as the intention was, as David Zierler reports, to create ‘a no man’s land across which the guerrillas cannot move’ then at least some American officials were perturbed at the spectre of the Western Front being let loose once again: ‘Defoliation is just too reminiscent of gas warfare.’ Their objections were dismissed, however, and the US Air Force expressed considerable satisfaction at the results: ‘herbicide operations in the Republic of Vietnam have proved to be very useful as a tactical weapon.’ Those on the ground had a different view. ‘We didn’t know anything about Agent Orange beyond the fact that it was a failure,’ declared Nathaniel Tripp. The brute fact was that removing the forest cover made movement more difficult for American troops too. Agent Orange turned the surviving vegetation into a slimescape and, worse, allowed the hated vines to multiply:

‘During the year or two that had elapsed since [Agent Orange] had been sprayed on the woods, the “wait-a-minute” vines seemed to have developed a liking for the stuff and taken over like a kudzu horror movie. The long, prickly vines hung in festoons from the stark skeletons of poisoned trees and covered the ground with a shoulder-high thicket. Sometimes it would take an hour to move forward a kilometer, hacking through the vines while the sun beat down unmercifully. Extra water was frequently dropped by helicopter between stream crossings, but men kept collapsing from heat exhaustion nonetheless, and we all had to stop and wait again while they were medevaced out’.

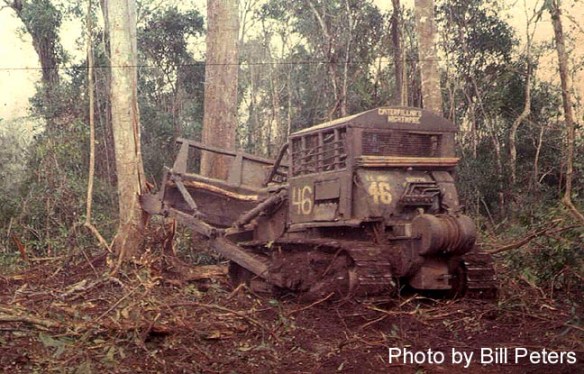

And clearing the rainforest exposed American patrols to more than the sun’s harsh rays. Later Tripp and his platoon were part of a division tasked with securing a route used to supply a detachment of forty Rome Plows – giant armoured bulldozers – that were busy ‘flattening mile after mile of woods’. ‘It was something to see from the air,’ he recalled, ‘like battalions of tornadoes had just passed through leaving nothing but a shattered tangle of mud and tree trunks and root masses.’ But again, the ground provided a different perspective:

‘Digging in was all but impossible, but we did the best we could in the pouring rain. The ground was covered everywhere with a mat of logs and branches, all interwoven and compacted, three to five feet thick and mixed with gummy gray clay. Surely, America had triumphed over the woods at last, and created a place that was impossible for anyone to hide in. Now, we were trying to hide in it, while the Viet Cong watched from the dark woods just meters away on both sides of the swath.’

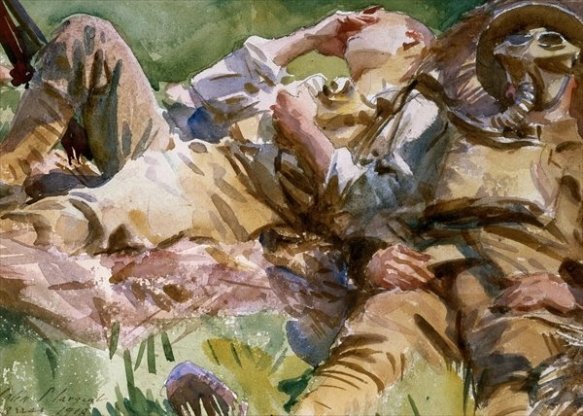

And yet, even in this ‘landscape of hopelessness’, as Tripp called it, there were precious moments of relief and even of redemption. Jacobs knew that ‘war destroys everything it touches’, but sometimes he found himself marvelling at ‘the natural beauty that surrounded us.’ Just when Delezen was in despair – ‘There is no beauty here, only destruction’ – he found a wild flower near an abandoned, half-filled fighting hole. ‘Like a rare jewel, it seems misplaced; there is no place for beauty here.’ But then:

‘I remove the sweat soaked leather bush glove from my hand and drop to one knee to touch the delicate petals. My hand is caked with slippery mud, a mixture of red dust from Route 9 and sweat; the hand seems filthy and crude against the soft purple and white flower. I decide not to touch it; I do not want to spoil this last bit of beauty and purity that has somehow escaped the Devil’s grasp.

‘I look toward the team that continues to move on without me; I am reluctant to leave the petite blossom unprotected. Quickly, I gather a small pile of rusty ration cans and place them around the frail green stem. Perhaps the cans will offer protection; the team is looking back at me, I have to rejoin them. I want to take the flower with me but it will only wither and die in the heat. I have done all that I can to protect it from the madness. For a brief moment, I have escaped the hell of war and entered a peaceful sanctuary where care and compassion still exist…. As I move away from the little pile of rusty cans, occasionally I look back; with each glance the soft colors of the flower fade until they blend into the dry-green of the tortured vegetation.’

It’s an affecting passage in which Delezen joins his forebears on the Western Front in affirming the stubborn persistence of a pastoral nature, even in a tropical rainforest, but the most elegiac moment I know comes towards the end of Matterhorn. Marlantes’ young lieutenant thinks of the jungle ‘already regrowing around him to cover the scars they had created’:

‘Mellas felt a slight breeze from the mountains rustling across the grass valley below him to the north. He was acutely aware of the natural world. He imagined the jungle, pulsing with life, quickly enveloping Matterhorn, Eiger, and all the other shorn hilltops, covering everything. All around him the mountains and the jungle whispered and moved, as if they were aware of his presence but indifferent to it.’

In speaking so directly to the recuperative, regenerative capacity of even a militarised nature, I suspect Marlantes is also expressing a desperate hope that those who have brutalised so many of its life-forms might find redemption too.