Back in the trenches again, revising “Gabriel’s Map”, and I see that the former President of the Royal Geographical Society – rather better known as Michael Palin (“This President is no more! He has ceased to be…. This is an EX-PRESIDENT!!”) – appears in a new BBC2 drama [also starring Ben Chaplin and Emilia Fox, left] based on the story of The Wipers Times, a trench newspaper written and printed on the Western Front during the First World War.

Back in the trenches again, revising “Gabriel’s Map”, and I see that the former President of the Royal Geographical Society – rather better known as Michael Palin (“This President is no more! He has ceased to be…. This is an EX-PRESIDENT!!”) – appears in a new BBC2 drama [also starring Ben Chaplin and Emilia Fox, left] based on the story of The Wipers Times, a trench newspaper written and printed on the Western Front during the First World War.

This is Palin’s first dramatic role in twenty years (other then being President of the RGS). Many readers will no doubt immediately think of the far from immortal Captain Blackadder in Blackadder Goes Forth (in which case see this extract from J.F. Roberts‘ The true history the Blackadder – according to Rowan Atkinson, “Of all the periods we covered it was the most historically accurate” – and compare it with this interview with Pierre Purseigle).

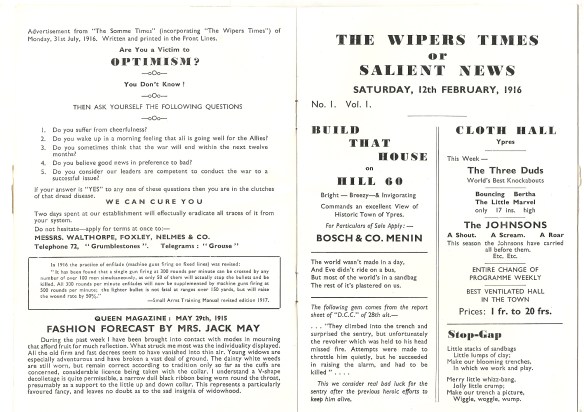

But since the script for The Wipers Times has been co-written by Ian Hislop (with Nick Newman) the Times is inevitably being described as a sort of khaki Private Eye: Cahal Milmo in the Independent says that ‘its rough-and-ready first edition was a masterclass in the use of comedy against industrialised death and military officialdom.’

So it was, but the appropriate critical comparison is with Punch, which Esther MacCallum-Stewart pursues in ingenious depth here. The French satirical magazine Le canard enchaîné (which is in many ways much closer to the Eye) started publication in 1915 and was much more critical. But for most of the war, MacCullum-Stewart says, Punch enforced ‘a strict code of “comedy as usual” interspersed by patriotic statements which hardly pastiched anything except an enduring capacity for the British to show a stiff upper lip to all comers.’

That soon wore thin on the Western Front, and when Captain Fred Roberts – played by Chaplin – found a printing-press amongst the rubble of Ypres (“Wipers”) in February 1916 the Times was born (though a shortage of vowels meant that only one page could be set up and printed at a time).

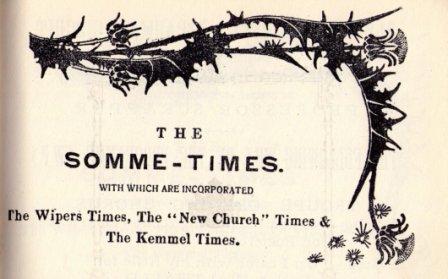

The title of the paper changed as the Division was re-deployed time and time(s) again. It had many targets in its sights, including the warrior poets:

‘We regret to announce that an insidious disease is affecting the Division, and the result is a hurricane of poetry. Subalterns have been seen with a notebook in one hand, and bombs in the other absently walking near the wire in deep communication with their muse.’

This is one of the most widely quoted passages in the paper, but MacCallum-Stewart explains that this is precisely because it could be squared with the mythology of the war which so many other contributions worked to undermine.

You can find other extracts here but my favourite – given how mud works its way into a central place in “Gabriel’s Map” and into one of the vignettes in “The nature of war” – is this satirical version of Rudyard Kipling‘s If (Kipling wrote the original in 1909 as advice to his son –”If you can keep your head when all about you are losing theirs…”: celebrated by the Daily Mail here):

If you can drink the beer the Belgians sell you,

And pay the price they ask with ne’er a grouse,

If you believe the tales that some will tell you,

And live in mud with ground sheet for a house,

If you can live on bully and a biscuit.

And thank your stars that you’ve a tot of rum,

Dodge whizzbangs with a grin, and as you risk it

Talk glibly of the pretty way they hum,

If you can flounder through a C.T. nightly

That’s three-parts full of mud and filth and slime,

Bite back the oaths and keep your jaw shut tightly,

While inwardly you’re cursing all the-time,

If you can crawl through wire and crump-holes reeking

With feet of liquid mud, and keep your head

Turned always to the place which you are seeking,

Through dread of crying you will laugh instead,

If you can fight a week in Hell’s own image,

And at the end just throw you down and grin,

When every bone you’ve got starts on a scrimmage,

And for a sleep you’d sell your soul within,

If you can clamber up with pick and shovel,

And turn your filthy crump hole to a trench,

When all inside you makes you itch to grovel,

And all you’ve had to feed on is a stench,

If you can hang on just because you’re thinking

You haven’t got one chance in ten to live,

So you will see it through, no use in blinking

And you’re not going to take more than you give,

If you can grin at last when handing over,

And finish well what you had well begun,

And think a muddy ditch’ a bed of clover,

You’ll be a soldier one day, then, my son.

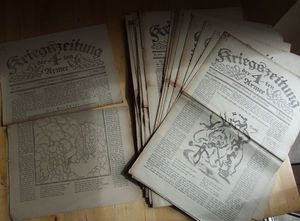

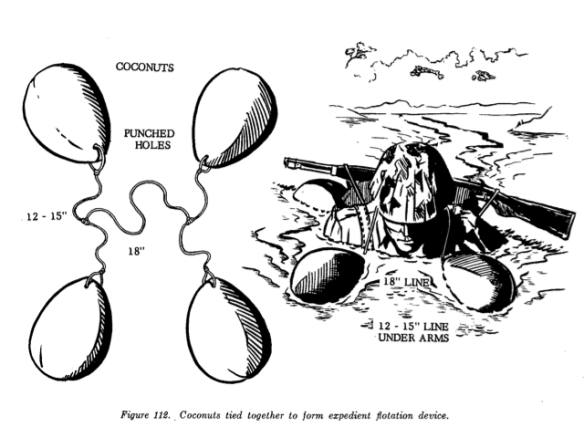

There were many other trench newspapers produced by the different armies on both sides. On the Allied side there were 100 or so British ones, for example, and perhaps four times as many French ones; there were perhaps 30 Canadian ones, and more Australian ones. Graham Seal has just published the first full-length study of Allied trench newspapers: The soldier’s press: Trench journals in the First World War (Palgrave-Macmillan 2013); you can sneak an extensive peak on Google Books (though contrary to what it says there, an e-edition is available at a ruinous price). As you can see from the image above, there were also trench newspapers on the other side too: see Robert Nelson, German soldiers newspapers of the First World War (Cambridge University Press, 2011). He also wrote a more general and thoroughly accessible survey of trench newspapers in War & History [2010] which is available here.

In the final edition of the Times, published after the end of the war, Roberts – by then a Lieutenant-Colonel – wrote this:

“Although some may be sorry it’s over, there is little doubt that the linemen are not, as most of us have been cured of any little illusions we may have had about the pomp and glory of war, and know it for the vilest disaster that can befall mankind.”