I’ve been working my way through the proofs of ‘The natures of war’, in which (among other things) I try to show that soldiers are not only vectors of military violence but also victims of it. My analysis fastens on the Western Front in the First World War, Northern Africa in the Second World War, and Vietnam – the final draft is under the DOWNLOADS tab and the published version should be up on the Antipode website later this month – but I hope it will be clear to readers that the implications of this claim , and the others in the essay, extend into our own present. They also intersect with my current research on casualty evacuation from war zones, 1914-2014.

So I’ve been interested in three recent contributions that detail the aftermath of war for those who fight them.

First, Veterans for Peace UK have worked with Darren Cullen to produce a short film, Action Man: Battlefield Casualties [see the clip above] in an attempt, as Charlie Gilmour explains over at Vice,

‘to show the shit beneath the shine of polished army propaganda. Featuring PTSD Action Man (“with thousand-yard stare action”), Paralysed Action Man (“legs really don’t work”) and Dead Action Man (“coffin sold separately”)…’ [see also my post on ‘The prosthetics of military violence‘]

In keeping with the project’s authors, Charlie insists – I think properly – that many of those who were sent to Afghanistan from the UK were child soldiers (and here I also recommend Owen Sheers‘ brilliant Pink Mist for an unforgettable portrayal of what happens when boys who grow up ‘playing war’ end up fighting it: see also here and here). As the project’s web site notes:

The UK is one of only nineteen countries worldwide, and the only EU member, that still recruits 16 year olds into its armed forces, (other nations include Iran and North Korea). The vast majority of countries only recruit adults aged 18 and above, but British children, with the consent of their parents, can begin the application process to join the army aged just 15…

It is the poorest regions of Britain that supply large numbers of these child recruits. The army has said that it looks to the youngest recruits to make up shortfalls in the infantry, by far the most dangerous part of the military. The infantry’s fatality rate in Afghanistan has been seven times that of the rest of the armed forces.

A study by human rights groups ForcesWatch and Child Soldiers International in 2013 found that soldiers who enlisted at 16 and completed training were twice as likely to die in Afghanistan as those who enlisted aged 18 or above, even though younger recruits are, for the most part, not sent to war until they are 18.

You can find another thoughtful reflection on child soldiers by Malcolm Harris over at the indispensable Aeon here. He doesn’t include the British Army in his discussion, but once you do you can see that the implications of this passage extend beyond its ostensible locus (Nigeria):

But can a child truly volunteer to join an army? Even when they enlist by choice, child soldiers do so under a set of constraining circumstances. UNICEF makes the choices sound easy: war or dancing, war or games, war or be a doctor. No rational child would pick the former for themselves, and that’s posed as evidence that their freedom has been taken from them. But when the choice is ‘soldier or victim’, voluntarism takes on a different meaning.

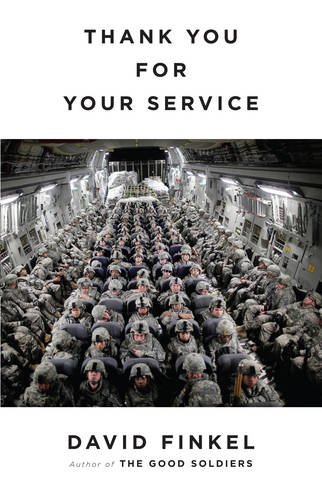

Second, moving across the Atlantic and providing an extended riff on the ‘thank you for your service’ gesture, the latest issue of New Left Review includes an essay by Joan Wypijewski, ‘Home Alone‘, that describes the journey home faced by many US veterans. She begins by putting David Finkel‘s compelling book in context:

The term ‘Thank You for Your Service’ developed early on in the long wars. Like ‘Support the Troops’, it was a way for a sheltered people to perform unity. In towns across America yellow ribbons, yellow lawn signs, balloons and car decals sprouted like team colours on game day. War would be a sport, the people spectators, and ‘Thank you for your service’ the high-five to combatants after quick and decisive victory. When that proved a vain hope, team spirit settled into the rhythms of commerce. ‘Support the Troops’ appeared the way ‘Buy American’ once had—a slogan on shop windows, billboards, bumper stickers. War was an enterprise, security its product, the people consumers, the soldiers trained workers and ‘Thank you for your service’ a kind of tip. As the enterprise (though hardly the business) failed, the signs faded, sometimes replaced by an image of folded hands, ‘Pray for Our Troops’. War had become a problem, the soldiers exhausted, the people clueless and ‘Thank you for your service’ a bit of empty etiquette, or a penance. By the time Finkel was writing [his book was published in October 2013], what remained among civilians was a desire to move on, and among soldiers, bitterness. ‘They wouldn’t be fucking thanking me if they knew what I did’, many would say, in almost exactly the same words.

Joan works her way through Finkel’s account, and then turns to Laurent Bécue-Renard’s Of Men and War, a documentary film – five years in the making, and the second instalment in a trilogy devoted to a ‘genealogy of wrath‘ – of Trauma Group sessions at a treatment centre in the Napa Valley:

‘What we have is embarrassing as shit’, a thick, tight young white man says in the Trauma Group. ‘You feel small—you feel defective.’ And so it goes, and so men trained for toughness talk of being weak and scared and monstrous, or just diligent. Of working in Mortuary Affairs: ‘breaking the rigour down’ to get the corpse of a 19-year-old who killed himself flat enough for a body bag, or untangling the remains of a group of faceless soldiers burned in a truck who are fused ‘like a bunch of rope’. They talk of their dreams, of their frightened wives. Maybe she moved out and got a restraining order before he came home, or maybe she has the divorce papers but is holding back as long as he’s getting help. ‘I have no clue what it’s like to be a woman married to a man twice your size and that’s lethal, in the military, and takes his rage out on you—someone that’s supposed to love you’, a former medic says. He is slim, white, deer-like. You don’t know his war story yet, and you don’t know when you’ll find out, if you’ll find out, but you listen as he and one after another after another deals with a world of pain. And maybe men balk, and maybe they storm out of the room, and maybe Gusman, whom you’ve also never really met but who is always there, has to remind them that ‘being a hostage to the war zone is not a life’. You follow them out of the room, taking smokes, meditating, visiting their wives or parents, calling on locals, trying to be well or pass for well, knowing they’re not. You watch their children doing typical childlike things, running, laughing in a high-pitched scream, and you feel anxious for everyone in the room. You itch to get back to the Trauma Group and, amazingly, don’t feel like a voyeur, because this isn’t war porn; this is the shit, as they say.

It isn’t beautiful or horrible, it just is. And you don’t like all of these people, but that isn’t the point. They are all struggling to be human again, and you have to ask yourself if you know what that means.

Not so much dressing but ‘addressing their wounds is a revolution’, Bécue-Renard insists, and you can see – literally so – what he means. Joan’s commentary ends with other, perhaps also revolutionary reflections. In America, she argues,

… there has been no serious debate on, let alone demand for, a universal draft as a democratic check against offensive war. We talk against empire, but are beneficiaries of the imperial state’s professional and technological adjustments to the anti-war movement’s past victories. We talk about the invisible draft but, perhaps encouraged by the bravery of Iraq Veterans Against the War, still hope that soldiers whose food, clothing, shelter, families and identity depend on the job of war-fighting will mutiny en masse. We talk, from time to time, about the culture of abuse in basic training and on military posts, but are silent on the regimens of discipline that are being hyper-enforced in anticipation of downsizing, in other words layoffs. And for the one thing the military, however twistedly, provides—belonging, solidarity, a sense of honour and family-feeling as against loneliness—we have no alternatives at all.

Finally, Duke University Press has announced that Zoe Wool‘s book, After War: the weight of life at Walter Reed, will be out soon:

In After War Zoë H. Wool explores how the American soldiers most severely injured in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars struggle to build some kind of ordinary life while recovering at Walter Reed Army Medical Center from grievous injuries like lost limbs and traumatic brain injury. Between 2007 and 2008, Wool spent time with many of these mostly male soldiers and their families and loved ones in an effort to understand what it’s like to be blown up and then pulled toward an ideal and ordinary civilian life in a place where the possibilities of such a life are called into question. Contextualizing these soldiers within a broader political and moral framework, Wool considers the soldier body as a historically, politically, and morally laden national icon of normative masculinity. She shows how injury, disability, and the reality of soldiers’ experiences and lives unsettle this icon and disrupt the all-too-common narrative of the heroic wounded veteran as the embodiment of patriotic self-sacrifice. For these soldiers, the uncanny ordinariness of seemingly extraordinary everyday circumstances and practices at Walter Reed create a reality that will never be normal.

Here are two of the endorsements:

“Hollywood films and literary memoirs tend to transform wounded veterans into tragic heroes or cybernetic supercrips. Zoë H. Wool knows better. In her beautifully written and deeply empathic study of veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan at Walter Reed, Wool shows us the long slow burn of convalescence and how the ordinary textures of domestic life unfold in real time. An important and timely intervention.” — David Serlin, author of Replaceable You: Engineering the Body in Postwar America.

“This brilliant and absorbing ethnography reveals how the violence of war is rendered simultaneously enduring and ephemeral for wounded American soldiers. Zoë H. Wool accounts for the frankness of embodiment and the unstable yet ceaseless processes through which the ordinary work of living is accomplished in the aftermath of serious injury. After War is a work of tremendous clarity and depth opening new sightlines in disability and the critical politics of the human body.” — Julie Livingston, author of Improvising Medicine: An African Oncology Ward in an Emerging Cancer Epidemic.