I’m finally working my way through Lauren Wilcox‘s impressive Bodies of Violence (see my earlier notice here), both to develop my ideas about corpography in general (see here, here and here) and to think through her arguments about drones in particular (in the penultimate chapter, ‘Body counts: the politics of embodiment in precision warfare’).

More on both later, but in the meantime there’s an extremely interesting symposium on the book over at The Disorder of Things that went on for most of last month. I’ll paste some extracts below to give a flavour of the discussion, which is well worth reading in its entirety.

Lauren Wilcox on ‘Bodies of Violence: Theorizing embodied subjects in International Relations’.

[W]hile war is actually inflicted on bodies, or bodies are explicitly protected, there is a lack of attention to the embodied dynamics of war and security…. I focus on Judith Butler’s work, in conversation with other theorists such as Julia Kristeva, Donna Haraway and Katherine Hayles. I argue, as have others, that there is continuity between her works on “Gender” from Gender Trouble and Bodies that Matter and her more explicitly ethical and political works such as Precarious Life and Frames of War. A central feature of Butler’s concept of bodily precarity is that our bodies are formed in and through violence….

My book makes three interrelated arguments:First, contemporary practices of violence necessitate a different conception of the subject as embodied. Understanding the dynamics of violence means that our conceptual frameworks cannot remain ‘disembodied’. My work builds on feminist and biopolitical perspectives that make the question of embodiment central to interrogating power and violence.

Second, taking the embodied subject seriously entails conceptualizing the subject as ontologically precarious, whose body is not given by nature but formed through politics and who is not naturally bounded or separated from others. Feminist theory in particular offers keen insights for thinking about our bodies as both produced by politics as well as productive of [politics].

Third, theorizing the embodied subject in this way requires violence to be considered not only destructive, but also productive in its ability to re-make subjects and our political worlds.

Antoine Bousquet on ‘Secular bodies of pain and the posthuman martial corps‘

[I]t increasingly appears that the attribution of rights is made to hinge on the recognition of their putative holder’s ability to feel pain, even where this might breach the species barrier or concern liminal states of human existence. As such, any future proponents of robot rights may well have to demonstrate less the sentient character of such machines than their sensitivity to pain (of course, it may well turn out that one entails the other). In relation to Bodies of Violence, if we are indeed to take the liberal conception of pain as purely negative as limiting (and we should perhaps not be too hastily dismissive of the moral and societal progresses that can be attributed to it), how does the recognition of ‘vulnerable bodies’ advocated by Wilcox depart from such an understanding? Is it simply a call for dismantling the asymmetries that render the pain of certain subjects less acknowledgeable than others or does it propose to actually restore a ‘positivity’ to suffering within a post-Christian worldview?…

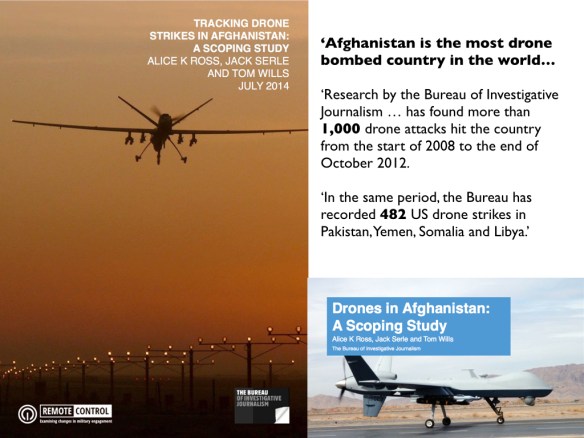

[A]s our knowledge of the human as an object of scientific study grows, our conception of the human as a unitary and stable entity becomes increasingly untenable, incrementally dissipating into a much broader continuum of being to be brought under the ambit of control. But where does such an expanded framing of human life leave the ‘normative model of the body’ as ‘an adult, young, healthy, male, cisgendered, and non-racially marked body’ (p.51) from which all minoritarian deviations are to be variously silenced, regulated and policed? Does the technicist efficiency-driven mobilisation of human life not corrode those normative hierarchies that do not contribute to or might even impede such a process? As Wilcox notes, the traditional investment of masculinist values in the military institution is unsettled when ‘the precision bomber or drone operator is seen as a “de-gendered” or “post-gendered” subject, in which it does not matter whether the pilot or operator is a male or female’ (p.135). Indeed, there seems to be no inherent reason why any number of deviations from the normative body would be an obstacle to their integration into the assemblage of military drones, to stay with that example. One can even conceive of cases where they could be beneficial – might not certain ‘disabilities’ offer particularly propitious terrain for the successful grafting of cybernetic prosthetics? In this context, corporeal plasticity and ontological porosity seem less like the adversaries of posthuman martiality than its necessary enablers.

Kevin McSorley on ‘Violence, norms and embodiment‘

[W]hat sense there might be any particular limits to the explanatory value of the key sensitising theoretical framework of embodied performativity and ‘normative violence’ that is deployed across all the numerous case studies considered here. Notwithstanding the supplementary engagement in certain chapters with further vocabularies of e.g. abjection or the posthuman to problematize bodily boundaries, the social embodiment of violent norms is really the major theoretical underpinning of all of the analyses undertaken in each of the five different case studies selected for interpretation. My sense was that Bodies of Violence was primarily concerned with establishing broad proof of concept that such theoretical deployment could work rather than engaging with detailed questions about the potential limits of its conceptual purchase and differences in explanatory value across the five varied case studies. The analyses undertaken propose if anything a near-universal analytic utility for the conceptual framework deployed in that there is a consistent interpretation that underlying normative violences operate within each of the different case studies. Additional comparative analysis, that specifically highlighted and attempted to think through where and why the interpretative framework might be especially productive, or indeed where and why it might feel less resonant and begin to break down, may potentially be insightful for further theoretical elaboration….

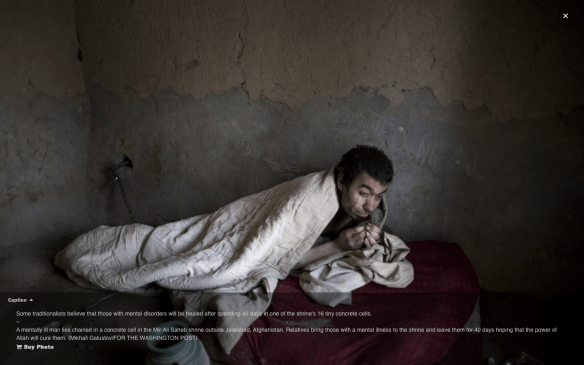

[W]hat might happen if the many embodied subjects theorised were able to more consistently speak back to theory, if their feelings and desires were more enfleshed in the analysis[?] Would the stability of this conceptual grid of intelligibility remain intact and unmoved if such encounters and dialogues were able to be staged, if the complex emotions and meaning-worlds of those socially embodied subjects actively negotiating normative violences could have a more audible place in the analysis?

Alison Howell on ‘Bodies, and Violence: Thinking with and beyond feminist IR‘

Can a theory rooted in a singular concept of ‘the body’ take full account of difference? Can it register the diverse ways in which different bodies become subject to and constituted through power and violence, or management and governance?

Wilcox does amply illustrate that there is no such unitary thing as ‘the body’… [but] there are long-standing traditions of theorizing embodiment and de-naturalizing ‘the body’ in anti-racist, postcolonial, and disability scholarship. These critical traditions should not be subsumed under the category of feminist scholarship, though they do certainly engage with feminist theory, often critically. They make unique contributions to theorizing embodiment, often through intersectional analyses.

Bodies of Violence does take up many texts from these traditions, but, for instance makes use of Margrit Shildrick’s and Jasbir Puar’s earlier work on the body, without also contemplating each of their more recent work on disability and debility…. A second line of inquiry a renewed focus on embodiment potentially suggests might center around the as-yet unmet potential for studying the role of medicine in IR. The sine qua non of medicine is, after all, the body, and if embodiment is important in the study of IR, then we should also be studying that system of knowledge and practice that has taken for itself authoritative dominion over bodies and that does the kind of productive work in relation to embodiment that Wilcox is interested in illuminating. As with disability studies, there is a significant literature, in this case emanating out of medical anthropology, medical sociology, bio-ethics and history of medicine….

But what of the book’s other titular concept: violence? Bodies of Violence suggests that to study embodiment is also to study violence. Yet violence is a concept and not merely a bare fact: ‘violence’ is a way of making sense and grouping together a number of practices….

Butler’s work has been central to de-essentializing both sex and gender, thus undermining radical feminist theories of violence that ascribe peacefulness to women and violence to men.Yet Butler’s work is less useful as a tool for excavating the particularly racist and Eurocentric forms that radical feminist thought on violence has taken. Instead, we might look towards Audre Lorde’s debates with Mary Daly, and to the succeeding traditions of anti-racist feminist thought.

Pablo K [Paul Kirby] on ‘Bodies, what matter?‘

Thinking about the value of bodies draws us into a contemplation of human life and its treatment. Which is why the mere act of recognising bodies can seem tantamount to calling for the preservation and celebration of life. Drawing attention to bodies to highlight an equality of concern due to those who have otherwise been rendered invisible is itself to engage in materialisation, making those bodies matter in a different way. It is a way to turn bodies (which are, on the whole, visible to us) into persons (entities with value and meaning which we may not recognise). And yet the body – precisely because it is inescapable and ubiquitous – is also evasive, and the form of its mattering elusive.

For Judith Butler, ‘mattering’ is the conjoined process of materialisation (suggestive of the way bodies are produced or come into being) and meaning (how bodies are recognised and invested with worth). The stress in contemporaneous and subsequent work on material-isation (on matter-ing) is thus intended to signal a break with ideas of matter as simply there, as idle or inert, and therefore as a kind of brute fact which is inescapable or consistent in its ahistorical role. Thus we are pushed to examine not the characteristics of matter, but the historical process of mattering; not the innate sex that simply bears gender constructions, but the moments which seemed to establish bodies (or body parts) as prior to the sign system which names them. The point is well taken, and has consequences for a theory of embodiment…

And so what is needed is a deeper excavation of the form, degree and value of mattering.

For the so-called new materialists, such a theory means attributing a certain agency to bodily substance (genetics, morphology, neural pathways, flesh itself). As Karen Barad has insisted:

any robust theory of the materialization of bodies would necessarily take account of how the body’s materiality – for example its anatomy and physiology – and other material forces actively matter to the process of materialization.

This is importantly different to saying that political regimes interpret and work bodies in distinct ways. In Bodies of Violence, despite the emphasis on how bodies produce politics, it is mainly politics that produces bodies. Or better, politics that intervenes on and shapes bodies.

Lauren Wilcox, ‘Theorizing embodiment and making bodies “matter“‘