Over the years I’ve learned much from the writings of Paul K. Saint-Amour, whose work on the violent intersections between modernism and air power has helped me think through my own project on bombing (‘Killing Space’) and, in a minor key, my analysis of cartography, aerial reconnaissance and ‘corpography’ on the Western Front in the First World War. A minimalist listing would include:

Over the years I’ve learned much from the writings of Paul K. Saint-Amour, whose work on the violent intersections between modernism and air power has helped me think through my own project on bombing (‘Killing Space’) and, in a minor key, my analysis of cartography, aerial reconnaissance and ‘corpography’ on the Western Front in the First World War. A minimalist listing would include:

Like me, Paul also has an essay in Pete Adey‘s co-edited collection, From above: war, violence and verticality (Hurst, 2013): ‘Photomosaics: mapping the Front, mapping the city’.

He has just published an important essay, ‘On the partiality of total war‘, in Critical inquiry 40 (2) (2014) 420-449, which has prompted this post. What I so admire about Paul’s writing is his combination of literary style – these essays are a joy to read, even when they address the bleakest of subjects – critical imagination and analytical acumen, and the latest essay is no exception.

His central point is that the idea of ‘total war’ – which, as he insists, was essentially an inter-war constellation – was deeply partial. It both naturalized and undermined a series of European imperialist distinctions between centre and periphery, peace and war:

‘… forms of violence forbidden in the metropole during peacetime were practiced in the colony, mandate, and protectorate, [and] … the distinction between peace and war was a luxury of the center. At the same time, by predicting that civilians in the metropole would have no immunity in future wars, it contributed to the erosion of the very imperial geography (center versus periphery) that it seemed to shore up.’

Hence the partiality of what he calls ‘the fractured problem-space of the concept’: ‘A truly total conception of war would have insisted openly on the legal, ethical, political, and technological connections between European conflagration and colonial air control’ (my emphasis).

Paul advances these claims, and enters into this fraught ‘problem-space’, by tracking the figure of a Royal Air Force officer, L.E.O. Charlton (left). A veteran of the First World War, Charlton was appalled by his experience of colonial ‘air control’ in Iraq in the 1920s (‘direct action by aeroplanes on indirect information by unreliable informants … was a species of oppression’: sounds familiar) but became a strenuous advocate of bombing civilians as the ‘new factor in warfare’ in the future. Convinced that Britain was exceptionally vulnerable to air attack, the only possible defence was extraordinary air superiority capable of landing devastating ‘hammer blows’.

Paul advances these claims, and enters into this fraught ‘problem-space’, by tracking the figure of a Royal Air Force officer, L.E.O. Charlton (left). A veteran of the First World War, Charlton was appalled by his experience of colonial ‘air control’ in Iraq in the 1920s (‘direct action by aeroplanes on indirect information by unreliable informants … was a species of oppression’: sounds familiar) but became a strenuous advocate of bombing civilians as the ‘new factor in warfare’ in the future. Convinced that Britain was exceptionally vulnerable to air attack, the only possible defence was extraordinary air superiority capable of landing devastating ‘hammer blows’.

Now others have traced the lines of descent from Britain’s ‘air policing’ in Palestine, Iraq and the North-West Frontier in the 1920s and 30s to its bomber offensive against Germany in the 1940s – ‘Bomber’ Harris notoriously cut his teeth in both Iraq and Palestine, though one historian treats this as precision dentistry – and still others have joined the dots from yesterday’s imperial borderlands to today’s: I’m thinking of Mark Neocleous‘s (re)vision of police power (‘Air power as police power‘, Environment and Planning D: Society & Space 31 (4) (2013) 578-93 and Priya Satia‘s genealogy of ‘Drones: a history from the Middle East‘, Humanity 5 (1) (2014) 1-31.

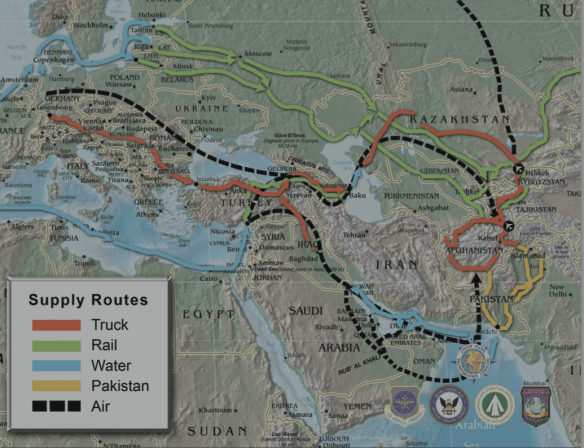

But Paul complicates these genealogies in important ways by showing how, within British military circles, war from the air was at once prosecuted and displaced/deferred. He argues that major air power theorists of the day reserved the category of ‘war’ for conflicts between sovereign states and relegated state violence ‘against colonial, mandate and protectorate populations’ to minor categories: ‘police actions, low-intensity conflicts, constabulary missions, pacification, colonial policing’. Indeed, at the Geneva Disarmament Conference in 1923 the British delegation sought to abolish all air forces except those deployed ‘for police purposes in certain outlying regions’. The manoeuvre failed, yet it wasn’t until 1977 that the first Additional Protocol to the Geneva Convention of 1949 recognised the right of subject populations to resist colonial domination, military occupation and racial repression, nominated such acts as constituting an ‘international conflict’, and extended to them the protections of international law. Several states have refused to ratify the AP, including the United States, Israel, Iran, India and Pakistan. Charlton’s original objection was to the use of air power outside declared war zones and against civilian subject populations: an objection that many would argue continues to have contemporary resonance in the CIA-directed drone strikes in Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia and elsewhere.

But Charlton’s masters (and, ultimately, Charlton himself) ‘dissevered’ the meaning of ongoing state violence in the periphery from prospective state violence at the centre. ‘Home is the space of the total war to come‘ – the Royal Air Force evidently believed that lessons learned in the colonies could be repatriated to the metropolis – and this would necessarily involve the breaching of state borders. War from the air thus dissolved the distinctions between military and civilian spaces, as Giulio Douhet prophesied in the 1920s:

‘By virtue of this new weapon, the repercussions of war are no longer limited by the farthest artillery range of guns, but can be felt directly for hundreds and hundreds of miles… The battlefield will be limited only by the boundaries of the nations at war, and all of their citizens will become combatants, since all of them will be exposed to the aerial offensives of the enemy. There will be no distinction any longer between soldiers and civilians.’

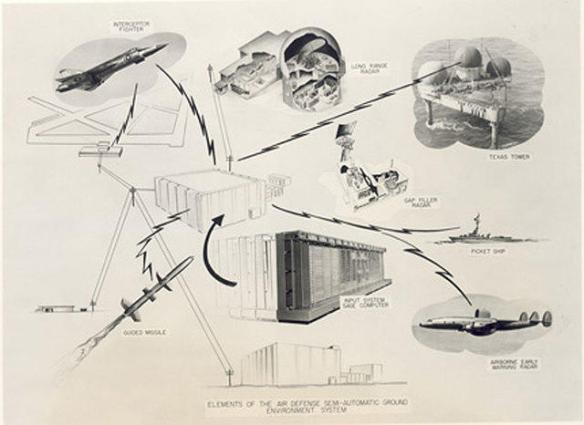

Few military experts in Britain talked about Douhet before the 1930s, but Charlton had read him in French translation, referring to him in his Cambridge lectures published as War from the air: past, present, future (1935): John Peaty calls him ‘Douhet’s leading disciple in Britain.’ But in Charlton’s view war from the air also redrew the contours of military violence so that they no longer lined fronts but bounded areas. In principle this transformation of the target space provided for two different strategies, though in practice the differences between them were as much ideological as they were substantive. Air strikes could take the form of either area bombing, levelling whole districts of cities, or so-called ‘precision bombing’ that would dislocate strategic nodes within a networked space, and it was this that Charlton believed was the key to aerial supremacy:

‘[T]he nation conceived by air-power theorists was a discrete entity unified both by the interlocking systems, structures, and forces that would constitute its war effort and by their collective targetability in the age of the bomber. As the proxy space for total war doctrine, in other words, air-power theory provided limitless occasions for representing the national totality. The common figures of “nerve centres,” “heart,” and “nerve ganglia” all participated in the emergent trope of an integrated national body whose geographical borders, war effort, and vulnerability were all coterminous.’

In War from the air, Charlton had advocated a devastating attack on the enemy capital:

‘It is the brain, and therefore the vital point. Injury to the brain means instant death, or paralysis, whereas injury to the body or the members, especially if it be a flesh-wound, may mean nothing at all, or, at most, a grave inconvenience.’

And in his contribution to The air defence of Britain, published in 1938, Charlton used the figure of the ‘national body’ to underscore what he saw as Britain’s vulnerability to air attack: ‘We are laid out, as if on an operating table, for the surgical methods of the bomber.’ As it turned out, of course, air strikes were even less ‘surgical’ than today’s aerialists try to claim, but as I showed in ‘Doors into nowhere’ (DOWNLOADS tab), these bio-physiological tropes were refined by Solly Zuckerman when he sought to provide a scientific basis for the combined bomber offensive during the Second World War.

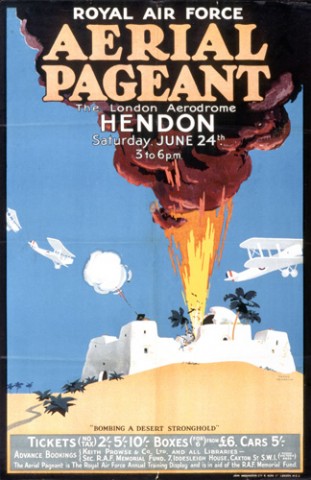

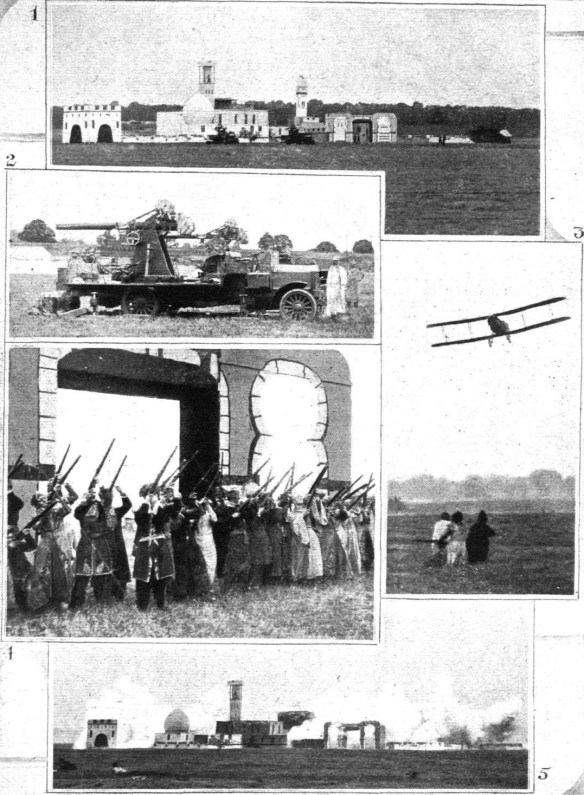

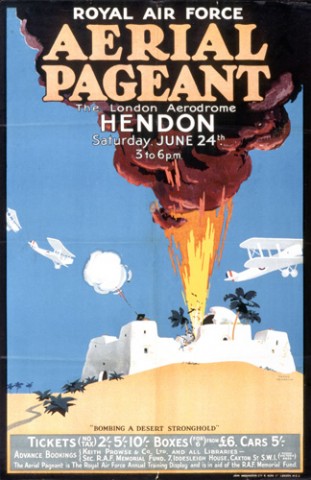

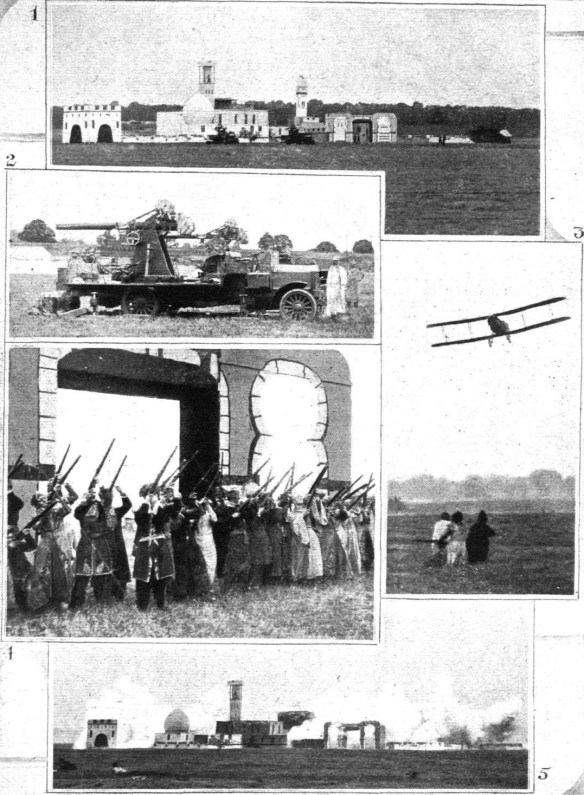

But precisely because the enabling experiments for these operations were carried out in a colonial laboratory, ‘outside the boundaries of the national body’, this couldn’t qualify as war – so this was ‘interwar’ in quite another sense too – and, Charlton notwithstanding, the ‘bombing demonstrations’ that took place in Iraq and elsewhere were not subject to much critical scrutiny or public outcry in Britain. On the contrary, within the metropole they were turned into popular entertainment at successive air displays at Hendon in North London in the 1920s (see below) (though, prophetically, by the 1930s, the pageant staged bombing runs against ‘the enemy’, and in War over England (1936) Charlton envisaged Britain forced to surrender after a devastating German air attack on, of all things, the Hendon Air Show) .

But precisely because the enabling experiments for these operations were carried out in a colonial laboratory, ‘outside the boundaries of the national body’, this couldn’t qualify as war – so this was ‘interwar’ in quite another sense too – and, Charlton notwithstanding, the ‘bombing demonstrations’ that took place in Iraq and elsewhere were not subject to much critical scrutiny or public outcry in Britain. On the contrary, within the metropole they were turned into popular entertainment at successive air displays at Hendon in North London in the 1920s (see below) (though, prophetically, by the 1930s, the pageant staged bombing runs against ‘the enemy’, and in War over England (1936) Charlton envisaged Britain forced to surrender after a devastating German air attack on, of all things, the Hendon Air Show) .

I think this argument could profitably be extended, because the desert ‘proving grounds’ had a cultural-strategic significance that, as both Priya Satia and Patrick Deer have shown, can be unravelled through another figure who also enters this problem-space, albeit in disguise, T.E. Lawrence or ‘Aircraftsman Ross’ (I’ve suggested some of these filiations in ‘DisOrdering the Orient’)….

I hope I’ve said enough to whet your appetite. This is a rich argument about war’s geographies, at once imaginative and material, and my bare-bones’ summary really doesn’t do it justice. An introductory footnote reveals that the essay, and presumably Paul’s previous ones, will appear in a book in progress (and prospect), Archive, Bomb, Civilian: Total War in the Shadows of Modernism, forthcoming from Oxford University Press.

You can find more on Josh’s work, including the larger Dronestream project here, while the saga of Apple’s rejections of Drones + is here. The first application in July 2012 was rejected because the app was ‘not useful or entertaining enough’ (really); a subsequent application was rejected because it provided content that ‘many audiences would find objectionable’ (yes indeed). Last September Apple made it clear that any app specifically about drone strikes would be rejected – unless, of course, it was a game like UAV Fighter – but ‘if you broaden your topic, then we can take another look.’ Hence Metadata+ (and look at its wonderful logo on the left).

You can find more on Josh’s work, including the larger Dronestream project here, while the saga of Apple’s rejections of Drones + is here. The first application in July 2012 was rejected because the app was ‘not useful or entertaining enough’ (really); a subsequent application was rejected because it provided content that ‘many audiences would find objectionable’ (yes indeed). Last September Apple made it clear that any app specifically about drone strikes would be rejected – unless, of course, it was a game like UAV Fighter – but ‘if you broaden your topic, then we can take another look.’ Hence Metadata+ (and look at its wonderful logo on the left).