Following from my previous post, I’ve been thinking a lot about bodies recently, and for two reasons.

The first is the workshop on War & Medicine I attended in Paris just before Christmas. It became very clear early on how difficult it is to determine when military violence comes to an end; Mary Dudziak has recently written about this in her War time: an idea, its history, its consequences (Oxford, 2012), largely from a legal point of view (and not without criticism), but it’s worth emphasising that the effects of violence continue long after any formal end to combat. This ought to be obvious, but it’s astonishing how often it’s ignored or glossed over.

The first is the workshop on War & Medicine I attended in Paris just before Christmas. It became very clear early on how difficult it is to determine when military violence comes to an end; Mary Dudziak has recently written about this in her War time: an idea, its history, its consequences (Oxford, 2012), largely from a legal point of view (and not without criticism), but it’s worth emphasising that the effects of violence continue long after any formal end to combat. This ought to be obvious, but it’s astonishing how often it’s ignored or glossed over.

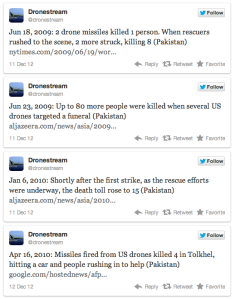

Think, for example, of the continuing toll of the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq, recovered in detail by Catherine Lutz (who was part of the workshop) and her colleagues at the Costs of War project, which shows how ‘the human and economic costs of these wars will continue for decades’.

Or think of the toxic environments produced by ecological warfare, by the use of depleted uranium in munitions, and by the continued deployment of land mines and cluster bombs – what Rob Nixon brilliantly calls the ‘slow violence’ produced by ‘ecologies of the aftermath’ (more on this in a later post):

Or think of the toxic environments produced by ecological warfare, by the use of depleted uranium in munitions, and by the continued deployment of land mines and cluster bombs – what Rob Nixon brilliantly calls the ‘slow violence’ produced by ‘ecologies of the aftermath’ (more on this in a later post):

‘In our age of depleted-uranium warfare, we have an ethical obligation to challenge the military body counts that consistently underestimate (in advance and in retrospect) the true toll of waging high-tech wars. Who is counting the staggered deaths that civilians and soldiers suffer from depleted uranium ingested or blown across the desert? Who is counting the belated fatalities from unexploded cluster bombs that lie in wait for months of years, metastasizing into landmines? Who is counting deaths from chemical residues left behind by so-called pinpoint bombing, residues that turn into foreign insurgents, infiltrating native rivers and poisoning the food chains? Who is counting the victims of genetic deterioration – the stillborn, malformed infants conceived by parents whose DNA has been scrambled by war’s toxins?’

(If you think we are winning the war on land-mines, especially in you are in Canada, read this).

These two contributions – and the conversations we had in Paris – rapidly displaced the lazy assumption of a politics of care in which the left mourns civilian casualties and the right military casualties. That there is a politics of care is clear enough, but there’s also a political geography: that’s written in to the biopolitical projects that are contained within so many late modern wars, and in Paris Omar Dewachi and Ghassan Abu-Sitta described how ‘care’ has become a means of controlling populations in wars in Iraq, Libya and Syria – a rather different sense of ‘surgical warfare’ from the one we’re used to – with states like Saudi Arabia and Qatar also funding the transfer of thousands of injured people from the war zones for treatment in hospitals in Egypt, Jordan and Lebanon.

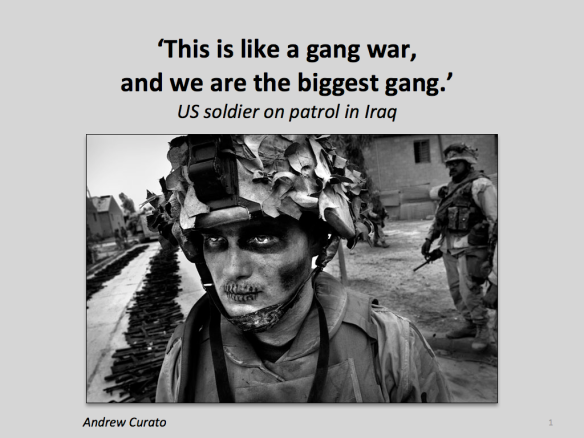

And two brilliant medical anthropologists, Ken Macleish and Zoe Wool, brought with them vivid, carefully wrought ethnographies of injured soldiers’ bodies. The American soldier may appear a figure of unprecedented invulnerabilty and astonishing violence – what Ken calls a figure of ‘technological magic’ produced by a ‘phantasmagoric technological empowerment of the body’ – but, as he and Zoe reminded us, soldiers are not only ‘the agents and instruments of sovereign violence’ but also its objects. Their studies took me to places I’ve never been and rarely thought about, but I’ve been thinking about two other dimensions of their work that combined to produce my second reason for thinking about bodies.

One is the historicity that is embedded in this process. Ken paraphrased Walter Benjamin‘s observation in the wake of the First World War – ‘the technological progress evident in modern warfare does not ensure the protection of the human body so much as it subjects it to previously unimaginable forms of harm and exposure’ – and linked it to John Keegan‘s claim in The face of battle that the military history of the twentieth-century was distinguished by the rise of ‘”thing-killing’ as opposed to man-killing weapons’ (the example he had in mind was heavy artillery). The other is the corporeality of the combat zone. Ken again: ‘You need not only knowledge of what the weapons and armor can do for you and to you but a kind of bodily habitus as well – an ability to take in the sensory indications of danger and act on them without having to think too hard about it first.’ In an essay ‘On movement’ forthcoming in Ethnos, Zoe develops this insight through an artful distinction between carnality and corporeality (which may require me to revise my vocabulary):

‘The analytics of movement is a turning toward emergent carnality, flesh, and the way it is seen and felt; proprioception and those other senses of sight, sound, touch, and taste through which a body and a space enact a meaningful, sensible articulation; visceral experiences forged and diagnosed through the trauma of war which also exceed its limits.’

And so to my second reason for thinking about bodies. Later this month I’m giving a lecture in the University of Kentucky’s annual Social Theory series. The theme this year is Mapping, and my title is ‘Gabriel’s Map‘. This is a riff on a phase from William Boyd‘s novel, An Ice-Cream War, that has haunted me ever since I first read it:

And so to my second reason for thinking about bodies. Later this month I’m giving a lecture in the University of Kentucky’s annual Social Theory series. The theme this year is Mapping, and my title is ‘Gabriel’s Map‘. This is a riff on a phase from William Boyd‘s novel, An Ice-Cream War, that has haunted me ever since I first read it:

‘Gabriel thought maps should be banned. They gave the world an order and reasonableness it didn’t possess.’

The occasion for the remark is a spectacularly unsuccessful British attempt to defeat a much smaller German force in November 1914 at Tanga in German East Africa; the young subaltern, Gabriel, rapidly discovers that there is a world of difference between what Clausewitz once called ‘paper war’ – a plan of attack plotted on the neat, stable lines of a map – and ‘real war’. What I plan (sic) to do is arc back from this exceptionally brutal campaign – which lasted two weeks longer than the war in Europe – to the western front. The two were strikingly different: the war in Africa was a war of movement and manoeuvre fought with the most meagre of military intelligence, whereas the central years of the war in Europe were distinguished by stasis and attrition and involved an extraordinary effort to maintain near real-time mapping of the disposition of forces.

The point here is to explore a dialectic between cartography and what I think I’m going to call corpography.

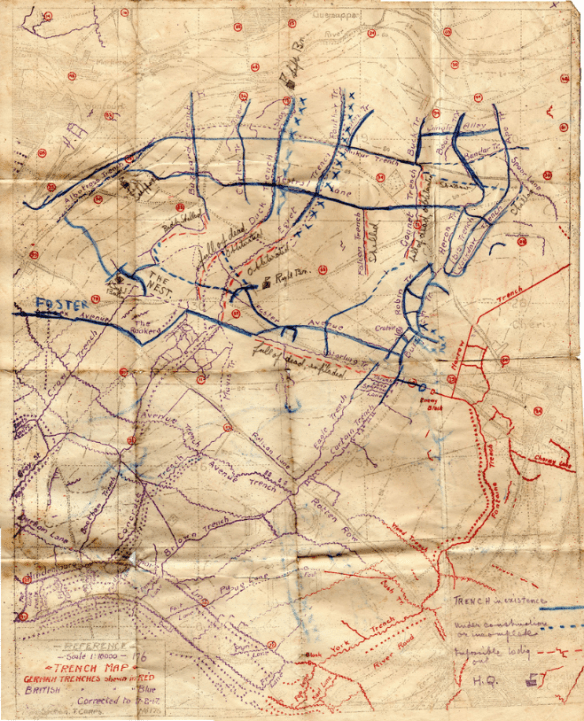

The first of these has involved working out the intimate relationship between mapping and aerial reconnaissance (what the Royal Flying Corps called ‘shooting the front’). There is a marvellously rich story to be told here which, among other things, shows that the stasis of trench warfare was Janus-faced: it was produced by a myriad of micro-movements – advances and withdrawals, raids and repulses – whose effectiveness depended not on the fixity of the map at all but on its more or less constant updating (which in turn means that this capacity isn’t the unique preserve of twenty-first century ‘digital navigation’). So here I’ll show how a casaced of millions of trench maps and aerial photographs was produced, distributed and then incorporated into the field of action through copies, re-drawings, sketches and annotations by front-line soldiers. I have wonderful, telling examples, like this one (look carefully at the annotations):

The first of these has involved working out the intimate relationship between mapping and aerial reconnaissance (what the Royal Flying Corps called ‘shooting the front’). There is a marvellously rich story to be told here which, among other things, shows that the stasis of trench warfare was Janus-faced: it was produced by a myriad of micro-movements – advances and withdrawals, raids and repulses – whose effectiveness depended not on the fixity of the map at all but on its more or less constant updating (which in turn means that this capacity isn’t the unique preserve of twenty-first century ‘digital navigation’). So here I’ll show how a casaced of millions of trench maps and aerial photographs was produced, distributed and then incorporated into the field of action through copies, re-drawings, sketches and annotations by front-line soldiers. I have wonderful, telling examples, like this one (look carefully at the annotations):

But I also want to show (as the map above implies: all those “full of dead” annotations) how, for these men, the battlefield was also literally a field: a vile, violent medium to be known not only (or even primarily) through sight but through touch, smell and sound: what Santanu Das memorably calls a ‘slimescape’ which was also a soundscape. This was a close-in terrain that was known through the physicality of the body as a sensuous, haptic geography:

But I also want to show (as the map above implies: all those “full of dead” annotations) how, for these men, the battlefield was also literally a field: a vile, violent medium to be known not only (or even primarily) through sight but through touch, smell and sound: what Santanu Das memorably calls a ‘slimescape’ which was also a soundscape. This was a close-in terrain that was known through the physicality of the body as a sensuous, haptic geography:

‘Amidst the dark, muddy, subterranean world of the trenches, the soldiers navigated space … not through the safe distance of the gaze but rather through the clumsy immediacy of their bodies: “crawl” is a recurring verb in trench narratives, showing the shift from the visual to the tactile.’

This was a ‘mapping’ of sorts – as Becca Weir suggests in ‘“Degrees in nothingness”: battlefield topography in the First World War’, Critical Quarterly 49 (4) (2007) 40-55 – and there is a dialectic between cartography and corpography.

I’ve been working my way through a series of diaries, memoirs and letters to flesh out its performance in detail, but the most vivid illustration of the entanglements of cartography and corpography that I’ve found – and that I suspect I shall ever find – is this extract from a ‘body density map’ for part of the Somme. This shows the standard trench map above a contemporary satellite photograph; each carefully ruled square is overprinted with the number of dead soldiers found buried in the first sweep after the war (between March and April 1919)…

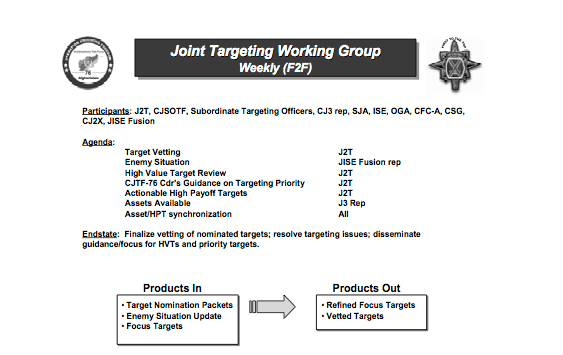

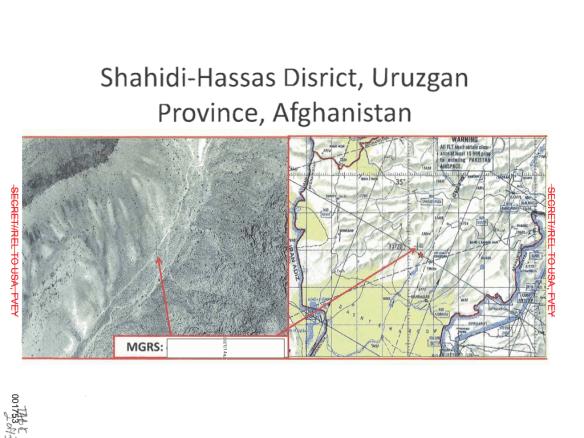

I won’t say more at present because I need to keep my powder dry for Kentucky, but I hope it will be clear by the end that, even though I’ll be talking about the First World War, I will also have been talking about the wars conducted in the shadows of the Twin Towers and the Pentagon.