Apart from trying to keep up with developments in Syria and Iraq – on which more shortly – I’ve also been continuing my reading on medical care on the Western Front. I’ve now finished The Backwash of War, and what a bleak little book it is. There’s very little about medical care – largely because in many respects there seems to have been very little of it in Ellen La Motte‘s field hospital – and much of the discussion is a deeply disturbing account of the cynicism of military violence: the generals who visit only to pin medals on the blankets of the dying, the contempt between medical orderlies and patients (who have no time for those who are not serving on the front lines), and the seemingly endless, agonising deaths of patients. But that was precisely what gave the author her title:

The sketches were written in 1915 and 1916, when the writer was in a French military field hospital, a few miles behind the lines, in Belgium. War has been described as “months of boredom, punctuated by moments of intense fright.” During this time at the Front, the lines moved little, either forward or backward, but were deadlocked in one position. Undoubtedly, up and down the long reaching kilometers of “Front” there was action, and “moments of intense fright” which produced fine deeds of valor, courage and nobility. But where there is little or no action there is a stagnant place, and in that stagnant place is much ugliness. Much ugliness is churned up in the wake of mighty, moving forces, and this is the backwash of war. Many little lives foam up in this backwash, loosened by the sweeping current, and detached from their environment. One catches a glimpse of them—often weak, hideous or repellent. There can be no war without this backwash.

In some part, perhaps, La Motte’s account reflects differences between British and French medical provision. Lyn Macdonald‘s The roses of no man’s land (which contains all sorts of insights into the geographies of medical evacuation and provision en passant) suggests that ‘Lying wounded on the battlefield [at Verdun] a French soldier was as good as dead, for there was little chance of his being brought in, and if he had the good luck to be rescued and taken to a hospital there was only one chance in three that he would leave it alive.’ By the end of the war, she continues, of France’s 1,300,000 war dead more than 400,000 had died of their wounds: ‘a proportion that was larger by far than those of any other nation and was due in considerable measure to the makeshift conditions and lack of skilled care in all but a few of the hospitals.’

This isn’t to romanticise the experience of those wounded in other armies, of course, but it adds another dimension to what Ana Carden-Coyne calls ‘the politics of wounds’. Her new book, due out in the fall, The politics of wounds: military patients and medical power in the First World War (Oxford University Press), is high on my reading list for my new research project:

The Politics of Wounds explores military patients’ experiences of frontline medical evacuation, war surgery, and the social world of military hospitals during the First World War. The proximity of the front and the colossal numbers of wounded created greater public awareness of the impact of the war than had been seen in previous conflicts, with serious political consequences.

Frequently referred to as ‘our wounded’, the central place of the soldier in society, as a symbol of the war’s shifting meaning, drew contradictory responses of compassion, heroism, and censure. Wounds also stirred romantic and sexual responses. This volume reveals the paradoxical situation of the increasing political demand levied on citizen soldiers concurrent with the rise in medical humanitarianism and war-related charitable voluntarism. The physical gestures and poignant sounds of the suffering men reached across the classes, giving rise to convictions about patient rights, which at times conflicted with the military’s pragmatism. Why, then, did patients represent military medicine, doctors and nurses in a negative light? The Politics of Wounds listens to the voices of wounded soldiers, placing their personal experience of pain within the social, cultural, and political contexts of military medical institutions. The author reveals how the wounded and disabled found culturally creative ways to express their pain, negotiate power relations, manage systemic tensions, and enact forms of ‘soft resistance’ against the societal and military expectations of masculinity when confronted by men in pain. The volume concludes by considering the way the state ascribed social and economic values on the body parts of disabled soldiers though the pension system.

But all this is about military patients: what of civilians who are wounded or become ill in war zones? The BackWash of War provides one vignette that is worth reporting in full. It’s titled ‘The Belgian Civilian’:

‘A big English ambulance drove along the high road from Ypres, going in the direction of a French field hospital, some ten miles from Ypres. Ordinarily, it could have had no business with this French hospital, since all English wounded are conveyed back to their own bases, therefore an exceptional case must have determined its route. It was an exceptional case—for the patient lying quietly within its yawning body, sheltered by its brown canvas wings, was not an English soldier, but only a small Belgian boy, a civilian, and Belgian civilians belong neither to the French nor English services. It is true that there was a hospital for Belgian civilians at the English base at Hazebrouck, and it would have seemed reasonable to have taken the patient there, but it was more reasonable to dump him at this French hospital, which was nearer. Not from any humanitarian motives, but just to get rid of him the sooner. In war, civilians are cheap things at best, and an immature civilian, Belgian at that, is very cheap. So the heavy English ambulance churned its way up a muddy hill, mashed through much mud at the entrance gates of the hospital, and crunched to a halt on the cinders before the Salle d’Attente, where it discharged its burden and drove off again.

‘The surgeon of the French hospital said: “What have we to do with this?” yet he regarded the patient thoughtfully. It was a very small patient. Moreover, the big English ambulance had driven off again, so there was no appeal. The small patient had been deposited upon one of the beds in the Salle d’Attente, and the French surgeon looked at him and wondered what he should do. The patient, now that he was here, belonged as much to the French field hospital as to any other, and as the big English ambulance from Ypres had driven off again, there was not much use in protesting….

‘A Belgian civilian, aged ten. Or thereabouts. Shot through the abdomen, or thereabouts. And dying, obviously. As usual, the surgeon pulled and twisted the long, black hairs on his hairy, bare arms, while he considered what he should do. He considered for five minutes, and then ordered the child to the operating room, and scrubbed and scrubbed his hands and his hairy arms, preparatory to a major operation. For the Belgian civilian, aged ten, had been shot through the abdomen by a German shell, or piece of shell, and there was nothing to do but try to remove it. It was a hopeless case, anyhow. The child would die without an operation, or he would die during the operation, or he would die after the operation….

‘After a most searching operation, the Belgian civilian was sent over to the ward, to live or die as circumstances determined. As soon as he came out of ether, he began to bawl for his mother. Being ten years of age, he was unreasonable, and bawled for her incessantly and could not be pacified. The patients were greatly annoyed by this disturbance, and there was indignation that the welfare and comfort of useful soldiers should be interfered with by the whims of a futile and useless civilian, a Belgian child at that. The nurse of that ward also made a fool of herself over this civilian, giving him far more attention than she had ever bestowed upon a soldier. She was sentimental, and his little age appealed to her—her sense of proportion and standard of values were all wrong. The Directrice appeared in the ward and tried to comfort the civilian, to still his howls, and then, after an hour of vain effort, she decided that his mother must be sent for. He was obviously dying, and it was necessary to send for his mother, whom alone of all the world he seemed to need. So a French ambulance, which had nothing to do with Belgian civilians, nor with Ypres, was sent over to Ypres late in the evening to fetch this mother for whom the Belgian civilian, aged ten, bawled so persistently.

‘She arrived finally, and, it appeared, reluctantly. About ten o’clock in the evening she arrived, and the moment she alighted from the big ambulance sent to fetch her, she began complaining. She had complained all the way over, said the chauffeur…. She had been dragged away from her husband, from her other children, and she seemed to have little interest in her son, the Belgian civilian, said to be dying. However, now that she was here, now that she had come all this way, she would go in to see him for a moment, since the Directrice seemed to think it so important….

‘She saw her son, and kissed him, and then asked to be sent back to Ypres. The Directrice explained that the child would not live through the night. The Belgian mother accepted this statement, but again asked to be sent back to Ypres. The Directrice again assured the Belgian mother that her son would not live through the night, and asked her to spend the night with him in the ward, to assist at his passing. The Belgian woman protested.

“If Madame la Directrice commands, if she insists, then I must assuredly obey. I have come all this distance because she commanded me, and if she insists that I spend the night at this place, then I must do so. Only if she does not insist, then I prefer to return to my home, to my other children at Ypres.”

‘However, the Directrice, who had a strong sense of a mother’s duty to the dying, commanded and insisted, and the Belgian woman gave way. She sat by her son all night, listening to his ravings and bawlings, and was with him when he died, at three o’clock in the morning. After which time, she requested to be taken back to Ypres. She was moved by the death of her son, but her duty lay at home. Madame la Directrice had promised to have a mass said at the burial of the child, which promise having been given, the woman saw no necessity for remaining.

“My husband,” she explained, “has a little estaminet, just outside of Ypres. We have been very fortunate. Only yesterday, of all the long days of the war, of the many days of bombardment, did a shell fall into our kitchen, wounding our son, as you have seen. But we have other children to consider, to provide for. And my husband is making much money at present, selling drink to the English soldiers. I must return to assist him.”

‘So the Belgian civilian was buried in the cemetery of the French soldiers, but many hours before this took place, the mother of the civilian had departed for Ypres. The chauffeur of the ambulance which was to convey her back to Ypres turned very white when given his orders. Everyone dreaded Ypres, and the dangers of Ypres. It was the place of death. Only the Belgian woman, whose husband kept an estaminet, and made much money selling drink to the English soldiers, did not dread it. She and her husband were making much money out of the war, money which would give their children a start in life. When the ambulance was ready she climbed into it with alacrity, although with a feeling of gratitude because the Directrice had promised a mass for her dead child.

“These Belgians!” said a French soldier. “How prosperous they will be after the war! How much money they will make from the Americans, and from the others.”‘

It would obviously be absurd to generalise from one vignette, but there’s clearly a different politics at work in this narrative, and a complex set of political geographies too. For a careful reading of La Motte’s account, in parallel with Mary Borden‘s The forbidden zone, you could do no better than Margaret Higonnet‘s introduction to her Nurses at the front: writing the wounds of the great war. I’ve now started on a series of accounts about the work of field ambulances, and one which resonates with the events described in La Motte’s vignette is William Boyd‘s letters from 7 March to 15 August 1915 published as With a field ambulance at Ypres (1916), which you can download free here.

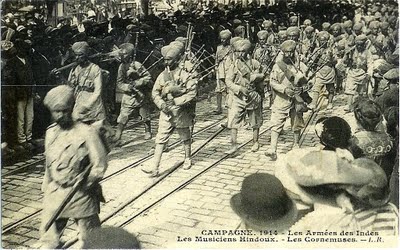

But all this – important – talk about writing the wounds of war should not blind us (me) to the role of visualising the wounds of war, and to the work done by artfully composed (and surely sanitised) images like the one that heads this post…