This is the ninth in a series of extended posts on Grégoire Chamayou‘s Théorie du drone and covers the fourth chapter in Part II, Ethos and psyche.

4 Psychopathologies of the drone

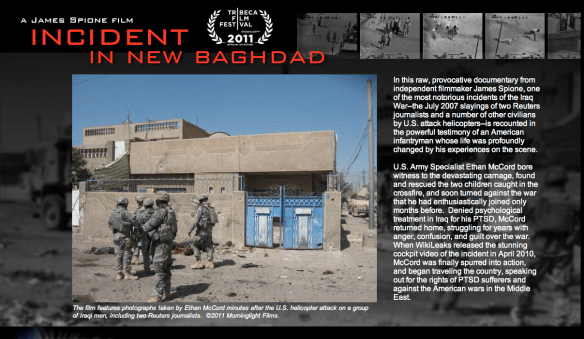

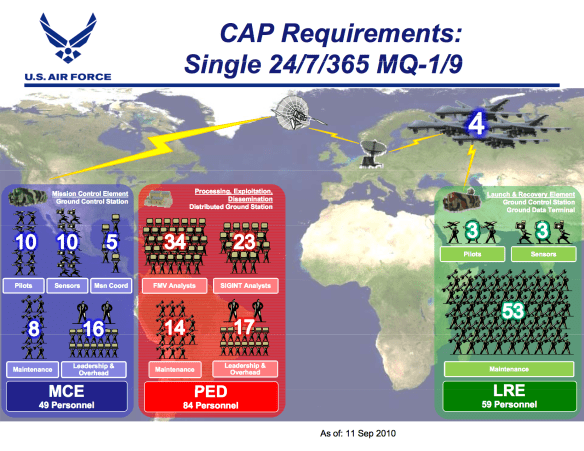

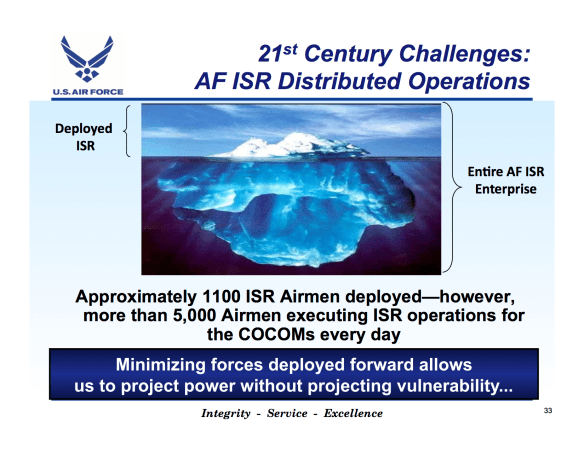

One of the most common media tropes in discussing ‘a day in the life’ of drone operators is their vulnerability to stress and, in particular, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Chamayou traces this to an Associated Press report by Scott Lindlaw in August 2008, which claimed that the crews who ‘operate Predator drones over Iraq via remote control, launching deadly missile attacks from the safety of Southern California 7,000 miles away, are suffering some of the same psychological stresses as their comrades on the battlefield.’ Similar stories have circulated in other media reports. The root claim is that, unlike pilots of conventional strike aircraft, drone crews see the results of their actions in close-up detail through their Full-Motion Video feeds and that they are required to remain on station to carry out a Battle Damage Assessment that often involves an inventory of body parts.

One recent study, ‘Killing in High Definition‘ by Scott Fitzsimmons and Karina Singha, presented at the International Studies Association in San Francisco earlier this year, makes the truly eye-popping suggestion that:

‘To reduce RPA operators’ exposure to the stress-inducing traumatic imagery associated with conducting airstrikes against human targets, the USAF should integrate graphical overlays into the visual sensor displays in the operators’ virtual cockpits. These overlays would, in real-time, mask the on-screen human victims of RPA airstrikes from the operators who carry them out with sprites or other simple graphics designed to dehumanize the victims’ appearance and, therefore, prevent the operators from seeing and developing haunting visual memories of the effects of their weapons.’

But in his original report Lindlaw admitted that ‘in interviews with five of the dozens of pilots and sensor operators at the various bases, none said they had been particularly troubled by their mission’, and Chamayou contends that the same discursive strategy – a bold claim discretely followed by denials – is common to most media reports of the stresses supposedly suffered by drone crews. More: he juxtaposes the crews’ own denial of anything out of the ordinary with the scorn displayed towards their remote missions by pilots of conventional strike aircraft who, in online chatrooms and message boards, regard the very idea as an insult to those who daily risk their lives in combat.

The argument Chamayou develops closely follows William Saletan‘s commentary in Slate:

[The AP story] shows that operating a real hunter, killer, or spy aircraft from the faraway safety of a game-style console affects some operators in a way that video games don’t. But it doesn’t show that firing a missile from a console feels like being there — or that it haunts the triggerman the same way. Indeed, the paucity of evidence — despite the brutal work shifts, the superior video quality, and the additional burden of watching the target take the hit — suggests that it feels quite different.

Chamayou’s reading is more aggressive. In his eyes, the repeated claim of vulnerability to stress emerged as a concerted response to criticisms of the supposed ‘Playstation mentality’ that attends remote killing and its reduction of war to a videogame. He insists that it’s little more than an attempt to apply ‘a veneer of humanity to an instrument of mechanical murder’ – ‘crying crocodile tears’ before devouring the prey – and that it rests on absolutely no empirical foundation. This raises the stakes, of course, and it’s only fair to note that Lindlaw’s interviews with drone crews did not talk up combat-related stress and in fact a USAF white paper dismissed as ‘sensational’ the claim that PTSD rates among RPA crews were higher than those suffered by their forward-deployed counterparts.

Indeed, Chamayou himself relies on a public lecture given by Colonel Hernando Ortega, a senior medical officer attached to the USAF Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance Agency in February 2012. Ortega reported USAF research that showed – conclusively – that drone crews are subject to often extraordinary stress. But this is primarily a matter of their conditions of work – the demands of paying close attention to a screen hour after hour – and the rapid shift alternations between work and home (‘telecommuting to the war zone’) that allow little or no time or space for decompression. Ortega explained that the symptoms rarely rise to the level of PTSD and are primarily the product of ‘operational stress’ rather than the result of combat-induced exposure to violence.

‘They don’t say [they are stressed] because we had to blow up a building. They don’t say because we saw people get blown up. That’s not what causes their stress — at least subjectively to them. It’s all the other quality of life things that everybody else would complain about too.’

Ortega could think of only one sensor operator who had been diagnosed with PTSD – a study by Wayne Chapelle, Amber Salinas and Lt Col Kent McDonald from the Department of Neurosurgery at the USAF School of Aerospace Medicine reported that 4 per cent of active duty RPA pilots and sensor operators were at ‘high risk for PTSD’ – but Ortega’s research questionnaires often revealed a sort of self-doubt over whether drone crews had made the right call when coming to the aid of troops in conflict rather than a direct response to a ‘physical threat event’:

‘Now it’s not to say that they don’t really feel about the physical threat to their brothers who are on the ground up there. The band of brothers … is not just in the unit. I believe it’s on the network, and I believe the communication tools that are out there has extended the band of brothers mentality to these crews who are in contact with guys on the ground. They know each other from the chat rooms. They know each other from the whatever, however they communicate. They do it every day, same thing all the time…. So that piece of the stress, I think, when something bad happens, that really is out there…’

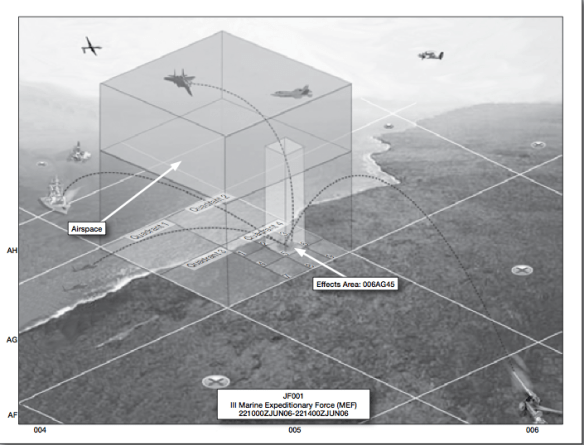

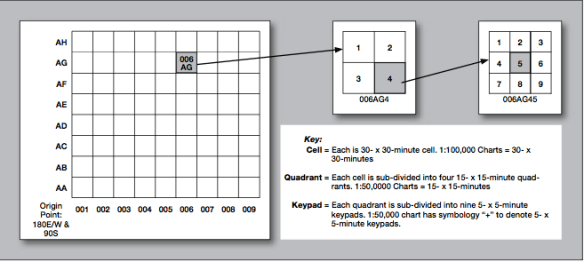

This sounds to me like the situation I described in ‘From a view to a kill’ (DOWNLOADS tab): the networked nature of remote operations draws operators into the conflict (which is why they so often insist that they are only 18″ from the battlefield, the distance from eye to screen) but on highly unequal, techno-culturally mediated terms that predispose them to identify with troops on the ground rather than with any others (or Others) in the immediate vicinity. What Chamayou takes from all this is Ortega’s conclusion:

‘The major findings of the work so far has been that the popularized idea of watching the combat was really not what was producing the most just day to day stress for these guys. Now there are individual cases — like I said, particularly with, for instance, when something goes wrong — a friendly fire incident or other things like that. Those things produce a lot of stress and … more of an existential kind of guilt… could I have done better? Did I make the right choices? What could I have done more?’

In fact for Chamayou the very idea of drone crews experiencing PTSD is an absurdity. According to the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM -5, 2013; revised from the previous version cited by Chamayou, this incorporates major changes from DSM-IV, but these do not materially alter his main point), PTSD is a trauma and stressor-related disorder brought about by exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence. The American Psychiatric Association explains:

In fact for Chamayou the very idea of drone crews experiencing PTSD is an absurdity. According to the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM -5, 2013; revised from the previous version cited by Chamayou, this incorporates major changes from DSM-IV, but these do not materially alter his main point), PTSD is a trauma and stressor-related disorder brought about by exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence. The American Psychiatric Association explains:

The exposure must result from one or more of the following scenarios, in which the individual:

• directly experiences the traumatic event;

• witnesses the traumatic event in person;

• learns that the traumatic event occurred to a close family member or close friend (with the actual or threatened death being either violent or accidental); or

• experiences first-hand repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of the traumatic event (not through media, pictures, television or movies unless work-related).

Drone crews do not ‘directly experience’ any traumatic event, Chamayou insists, and far from being ‘witnesses’ they are the perpetrators of trauma. Those last three words in the extract I’ve just quoted do open up a third scenario – which would leave open the possibility of being affected by high-definition exposure through the FMV feeds and the Battle Damage Assessments performed by drone crews – but Chamayou hones the role of the perpetrator to explore a different though not unrelated scenario.

He takes his cue from Karl Abraham‘s discussion of neuroses in the First World War:

‘It is not only demanded of these men in the field that they must tolerate dangerous situations — a purely “passive performance — but there is a second demand which has been much too little considered, I allude to the aggressive acts for which the soldier must be hourly prepared, for besides the readiness to die, the readiness to kill is demanded of him…. [In our patients the anxiety as regards killing is of a similar significance to that of dying.’

Chamayou is most interested in the development of this line of thought by psychologist/sociologist Rachel MacNair, who widens the field of PTSD to incorporate what she calls Perpetration-Induced Traumatic Stress (PITS): you can find a quick summary here. (McNair is a long-time peace activist and in accordance with the ‘consistent life ethic’ she has used her work on PITS to intervene in what she calls ‘the abortion wars’; she is also associated with the Center for Global Nonkilling: see here).

Chamayou is most interested in the development of this line of thought by psychologist/sociologist Rachel MacNair, who widens the field of PTSD to incorporate what she calls Perpetration-Induced Traumatic Stress (PITS): you can find a quick summary here. (McNair is a long-time peace activist and in accordance with the ‘consistent life ethic’ she has used her work on PITS to intervene in what she calls ‘the abortion wars’; she is also associated with the Center for Global Nonkilling: see here).

Her book was written too early to address the use of drones for remote killing, but Chamayou suggests that this would be an appropriate means of putting their ‘psychopathologies’ to the test. He thinks that individual operators lie somewhere between two poles: either they are indifferent to killing at a distance (the screen as barrier) or they feel culpable for the violence they have inflicted (the screen forcing them to confront the consequences of their actions). It is, he concludes, an open question: though his next chapter on ‘Killing at a distance’ proposes a series of answers.

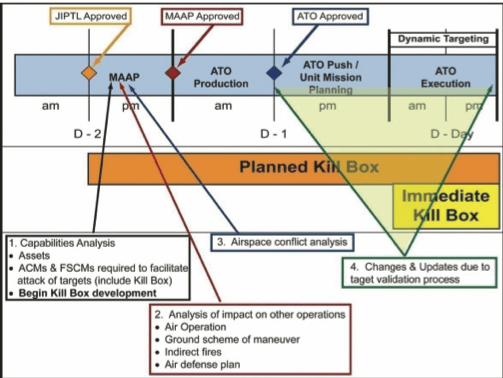

In fact, the USAF recognises the distinct possibility of PITS affecting drone crews, as this slide from a presentation by Chappelle and McDonald shows:

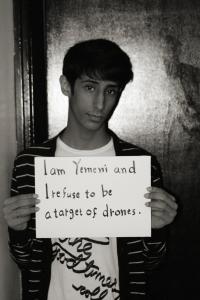

This year MacNair became President of Division 48 (Peace Psychology) of the American Psychological Association and instituted three Presidential Task Forces, the first of which specifically addresses drones. She writes:

‘Task Force 1 is examining “The Psychological Issues of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (Weaponized drones).” This will focus on the flying robots that kill, not the ones doing surveillance, nor the consumer drones that loom on the horizon. this is a very new field, with very little literature. We’ll look at what the psychological impact is on operators of the systems, the bureaucracy, surviving victims, and special therapeutic needs. The task force email for any feed-back or good literature citations or to request the full list of questions is dronetF@ peacepsych.org.’

The newsletter also includes a short statement from the next President of the Division, Brad Olson, setting out ‘Some thoughts for the Drone Task Force’ and an article by Marc Pilisuk on ‘The new face of war’.

Let me add three other comments.

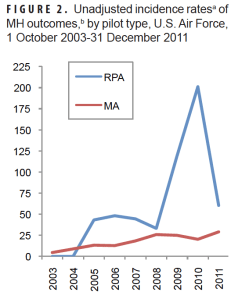

(1) To limit the discussion to PTSD is to set the bar very high indeed, and the evidence of lower-level combat-induced stress on drone crews is less straightforward than Chamayou makes out. In March 2013 Jean Otto and Bryant Webber reported the results of a study of ‘mental health outcomes’ covering the period 1 October 2003 to 31 December 2011 for 709 drone (RPA) pilots and 5, 526 pilots of manned aircraft (MA); they found that the crude incidence of adjustment, anxiety, depressive and other disorders among RPA pilots was considerably higher than for MA pilots, but once the samples were adjusted for age, number of deployments and other factors the ‘incidence rates among the cohorts did not significantly differ’ (my emphasis).

The study was experimental in all sorts of ways and it does not – could not – provide a fine-grained analysis of the nature of the pilots’ exposure to violence. We should bear in mind, too, that the study was inevitably limited by inhibitions, both formal and informal, on admitting to any form of stress within the military. But the report does suggest that it is a mistake to separate drone crews from the wider matrix of military violence and its effects in which they are embedded.

(2) If Chamayou is right in his suspicion that all this talk of drone crews being affected by what they see on their screens was a concerted strategy designed to disarm claims that remote operations reduce war to a videogame – in which case, not everybody in the Air Force was singing the same tune – the fact that most of them turn out to conduct their missions with equanimity does not prove the critics right: it does not follow that they take their responsibilities less seriously or more casually than the pilots of conventional strike aircraft. Pilots and sensor operators undoubtedly have recourse to gallows humour (Chamayou would no doubt say that this befits their role as ‘executioners’), and there are too many reported instances of language that I too find repugnant, though I see no reason not to expect the same amongst military personnel of all stripes. But there is also anecdotal evidence of situations in which pilots and their crews have been deeply affected by what they saw (and, yes, did). The testimony of at least one former operator, Brandon Bryant (above, left), who has been diagnosed with PTSD, suggests that those involved probably move between these extremes – between the two poles proposed by Chamayou – dis/connecting as their actions and reactions entangle with events on the screen/ground.

(2) If Chamayou is right in his suspicion that all this talk of drone crews being affected by what they see on their screens was a concerted strategy designed to disarm claims that remote operations reduce war to a videogame – in which case, not everybody in the Air Force was singing the same tune – the fact that most of them turn out to conduct their missions with equanimity does not prove the critics right: it does not follow that they take their responsibilities less seriously or more casually than the pilots of conventional strike aircraft. Pilots and sensor operators undoubtedly have recourse to gallows humour (Chamayou would no doubt say that this befits their role as ‘executioners’), and there are too many reported instances of language that I too find repugnant, though I see no reason not to expect the same amongst military personnel of all stripes. But there is also anecdotal evidence of situations in which pilots and their crews have been deeply affected by what they saw (and, yes, did). The testimony of at least one former operator, Brandon Bryant (above, left), who has been diagnosed with PTSD, suggests that those involved probably move between these extremes – between the two poles proposed by Chamayou – dis/connecting as their actions and reactions entangle with events on the screen/ground.

(3) The most careful review I know of what is a complicated and contentious field is Peter Asaro, ‘The labor of surveillance and bureaucratized killing: new subjectivities of military drone operators, Social semiotics 23 (2) (2013) 196-22. This combines medico-military studies, media reports and an artful reading of Omer Fast‘s film, 5,000 Feet is the Best. as Peter says, there are many jobs that involve surveillance and many jobs that involve killing, but

‘What makes drone operators particularly interesting as subjects is not only that their work combines surveillance and killing, but also that it sits at an intersection of multiple networks of power and technology and visibility and invisibility, and their work is a focal point for debates about the ethics of killing, the effectiveness of military strategies for achieving political goals, the cultural and political significance of lethal robotics, and public concerns over the further automation of surveillance and killing.’

It’s a tour de force that navigates a careful passage between the ‘heroic’ and ‘anti-heroic’ myth of drones. Here is what I take to be the key passage from his conclusion:

‘On the one hand, drone operators do not treat their job in the cavalier manner of a video game, but they do recognize the strong resemblance between the two. Many drone operators are often also videogame players in their free time, and readily acknowledge certain similarities in the technological interfaces of each. Yet the drone operators are very much aware of the reality of their actions, and the consequences it has on the lives and deaths of the people they watch via video streams from half a world away, as they bear witness to the violence of their own lethal decisions. What they are less aware of … is that their work involves the active construction of interpretations. The bodies and actions in the video streams are not simply ‘‘given’’ as soldiers, civilians, and possible insurgents – they are actively constructed as such. And in the process of this construction the technology plays both an enabling and mediating role. I use the term ‘‘mediating’’ here to indicate that it is a role of translation, not of truth or falsity directly, but of transformation and filtering. On the one hand there is the thermal imaging that provides a view into a mysterious and hidden world of relative temperatures. And thus these drone technologies offer a vision that contains more than the human alone could ever see. On the other hand we can see that the lived world of human experience, material practices, social interactions, and cultural meanings that they are observing are difficult to properly interpret and fully understand, and that even the highest resolution camera cannot resolve the uncertainties and misinterpretations. There is a limit to the fidelity that mediation itself can provide, insofar as it cannot provide genuine social participation and direct engagement. This applies not only to both surveillance and visuality, which is necessarily incomplete, but also to the limited forms of action and engagement that mediating technologies permit. While a soldier on the ground can use his or her hands to administer medical aid, or push a stalled car, as easily as they can hold a weapon, the drone operator can only observe and choose to kill or not to kill. Within this limited range of action, meaningful social interaction is fundamentally reduced to sorting the world into friends, enemies, and potential enemies, as no other categories can be meaningfully acted upon.’

There’s a discussion of these various issues, including many of the people mentioned in this post, at HuffPost Live here.