Living under drones is both a chilling report and a nightmare reality. In November 2014, in a New Yorker essay called ‘The unblinking stare‘, Steve Coll reported a conversation with Malik Jalal from North Waziristan:

‘Drones may kill relatively few, but they terrify many more… They turned the people into psychiatric patients. The F-16s might be less accurate, but they come and go.’

Now Reprieve has put a compelling face to the name – to a man who believes, evidently with good reason, that he has been included in the CIA’s disposition matrix that lists those authorised for targeted killing.

‘Malik’ is an honorific reserved for community leaders, and Jalal is one of the leaders of the North Waziristan Peace Committee (NWPC). Its main role is to try to keep the peace between the Taliban and local authorities, and it was in that capacity that he attended a Jirga in March 2011. He says this was on 27 March, but I think it must have been the strike that killed 40 civilians at Datta Khel on 17 March (see the summary from the Bureau of Investigative Journalism here and my post here).

Here are the relevant passages from my ‘Dirty dancing’ essay, following from a discussion of Pashtunwali and customary law in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (I’ve omitted the footnotes and references):

***

‘In short, if many of the Pashtun people in the borderlands are deeply suspicious of and even resentful towards Islamabad (often with good reason) they are ‘neither lawless nor defenceless.’

‘Yet the trope of ‘lawlessness’ persists, and it does important work. ‘By alleging a scarcity of legal regulation within the tribal regions,’ Sabrina Gilani argues, ‘the Pakistani state has been able to mask its use of more stringent sets of controls over and surveillance within the area.’ The trope does equally important work for the United States, for whom it is not the absence of sovereign power from the borderlands that provides the moral warrant for unleashing what Manan Ahmad calls its ‘righteous violence’. While Washington has repeatedly urged Islamabad to do much more, and to be less selective in dealing with the different factions of the Taliban, it knows very well that Pakistan has spasmodically exercised spectacular military violence there. But if the FATA are seen as ‘lawless’ in a strictly modern sense – ‘administered’ but not admitted, unincorporated into the body politic – then US drone strikes become a prosthetic, pre-emptive process not only of law enforcement but also of law imposition. They bring from the outside an ‘order’ that is supposedly lacking on the inside, and are reconstituted as instruments of an aggressively modern reason that cloaks violence in the velvet glove of the law.

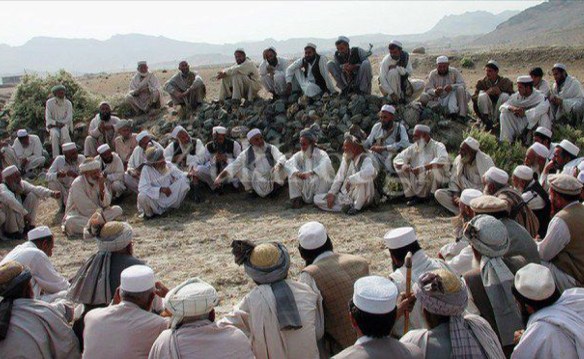

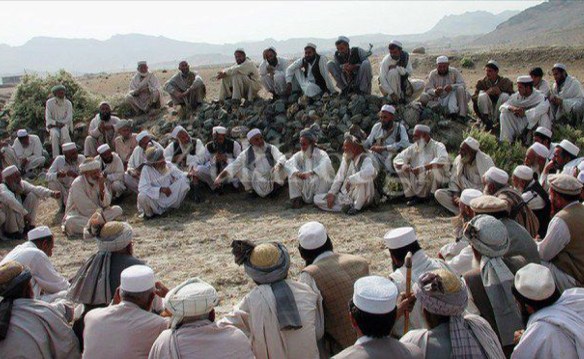

And yet the CIA’s own willingness to submit to the principles and procedures of modern law is selective and conditional; we know this from the revelations about torture and global rendition, but in the borderlands the agency’s disregard for the very system it purports to defend also exposes any group of men sitting in a circle with guns to death: even if they are gathered as a Jirga. On 27 January 2011 CIA contractor Raymond Davis was arrested for shooting two young men in Lahore. The targeted killing program was suspended while the United States negotiated his release from custody, agreeing to pay compensation to the victims’ families under Sharia law so that he could be released from the jurisdiction of the court. On 16 March, the day after Davis’s release, a Jirga was convened in Dhatta Khel in North Waziristan. A tribal elder had bought the rights to log an area of oak trees only to discover that the land also contained chromite reserves; the landowner was from a different tribe and held that their agreement covered the rights to the timber but not the minerals, and the Jirga was called to resolve what had become an inter-tribal dispute between the Kharhtangi and the Datakhel. Maliks, government officials, local police and others involved in the affair gathered at the Nomada bus depot – a tract of open ground in the middle of the small town – where they debated in two large circles. Agreement was not reached and the Jirga reconvened the next morning. Although four men from a local Taliban group were present, the meeting had been authorised by the local military commander ten days earlier and was attended by a counsellor appointed by the government to act as liaison between the state, the military and the maliks. It was also targeted by at least one and perhaps two Predators. At 11 a.m. multiple Hellfire missiles roared into the circles. More than forty people were killed, their bodies ripped apart by the blast and by shattered rocks, and another 14 were seriously injured.

There is no doubt that four Taliban were present: they were routinely involved in disputes between tribes with competing claims and levied taxes on chromite exports and the mine operators. But the civilian toll from the strike was wholly disproportionate to any conceivable military advantage, to say nothing of the diplomatic storm it set off, and several American sources told reporters that the attack was in retaliation for the arrest of Davis: ‘The CIA was angry.’ If true, this was no example of the dispassionate exercise of reason but instead a matter of disrespecting the resolution offered by Sharia law and disordering a customary judicial tribunal. Even more revealing, after the strike an anonymous American official who was supposedly ‘familiar with the details of the attack’ told the media that the meeting was a legitimate military target and insisted that there were no civilian casualties. Serially: ‘This action was directed against a number of brutal terrorists, not a county fair’; ‘These people weren’t gathering for a bake sale’; ‘These guys were … not the local men’s glee club’; ‘This was a group of terrorists, not a charity car wash in the Pakistani hinterlands.’ The official – I assume it was the same one, given the difference-in-repetition of the statements – provided increasingly bizarre and offensively absurd descriptions of what the assembly in Datta Khel was not: he was clearly incapable of recognising what it was. Admitting the assembly had been a properly constituted Jirga would have given the lie to the ‘lawlessness’ of the region and stripped the strike of any conceivable legitimacy. The area was no stranger to drone attacks, which had been concentrated in a target box that extended along the Tochi valley from Datta Khel through Miran Shah to Mir Ali, but those responsible for this attack were clearly strangers to the area.

***

‘Like others that day,’ Jalal concedes, ‘I said some things I regret. I was angry, and I said we would get our revenge. But, in truth, how would we ever do such a thing? Our true frustration was that we – the elders of our villages – are now powerless to protect our people.’

This was the fourth in a series of strikes that Jalal believes targeted him:

‘I have been warned that Americans and their allies had me and others from the Peace Committee on their Kill List. I cannot name my sources [in the security services], as they would find themselves targeted for trying to save my life. But it leaves me in no doubt that I am one of the hunted.’

He says he is an opponent of the drone wars – but if that were sufficient grounds to be included on the kill list it would stretch into the far distance.

He also says that the Americans ‘think the Peace Committee is a front’ working to create ‘a safe space for the Pakistan Taliban.’

‘To this I say: you are wrong. You have never been to Waziristan, so how would you know?’

And he describes the dreadful impact of being hunted on him and his family:

‘I soon began to park any vehicle far from my destination, to avoid making it a target. My friends began to decline my invitations, afraid that dinner might be interrupted by a missile.

‘I took to the habit of sleeping under the trees, well above my home, to avoid acting as a magnet of death for my whole family. But one night my youngest son, Hilal (then aged six), followed me out to the mountainside. He said that he, too, feared the droning engines at night. I tried to comfort him. I said that drones wouldn’t target children, but Hilal refused to believe me. He said that missiles had often killed children. It was then that I knew that I could not let them go on living like this.’

And so he has travelled to Britain to plead his case:

‘I came to Britain because I feel like Britain is like a younger brother to America. I am telling Britain that America doesn’t listen to us, so you tell them not to kill Waziristanis.’

You can hear an interview with him on BBC’s Today programme here.

In you think Britain is distanced from all this, read Reprieve‘s latest report on ‘Britain’s Kill List‘ here (which focuses on the Joint Prioritised Effects List in Afghanistan and its spillover into Pakistan) and Vice‘s investigation into the UK’s role in finding and fixing targets in Yemen here.